The seven jewels of the aryas: Material generosity

Part of a series of short talks on the Seven Jewels of the Aryas.

- The benefits of material generosity

- Pondering the reason for the order of the seven jewels

- Giving of material possessions and wealth

We’ve been talking about the seven jewels of the aryas. I wanted to read you the verse. Again, this is from Nagarjuna’s

Faith and ethical discipline

Learning, generosity,

an untainted sense of integrity,

and consideration for others,

and wisdom,

are the seven jewels spoken of by the Buddha.

Know that other worldly riches have no meaning (or no value.)

In Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland by Atisha, the order is slightly different. This one has the wealth of faith, the wealth of ethics, then the wealth of giving. The first one had ethical conduct, learning, and then generosity. This one has generosity, and then the wealth of learning, the wealth of conscience, the wealth of remorse. You can see how many different translations there are. “And the wealth of insight. These are the seven riches.”

Sometimes it’s hard to figure out, between two translators, that it was actually the same verse they were translating. This one, it’s easier, because it’s a list. But many times you look at it and it’s like, two translators, and is this the same verse they’re both translating?

We did faith, we did ethical conduct last time. I was going by the Atisha version and was going to talk about generosity today. Although I must say that I’ve been trying to ponder why these seven are in the order that they’re in. Faith being first, that makes sense. Wisdom being the last, that makes sense. Ethical conduct being the second one? In one way that makes sense, but in another way it would make sense for giving to be the second one, because in the list of the perfections it comes before ethical conduct. And also, in the Pali tradition, when they talk about the practice for lay people, they say giving first, ethical conduct, and meditation. They say giving first because giving (and it also comes in our tradition, too, why is generosity before ethical conduct in the list of the perfections), is because giving is something that everybody does. Whether you’re religious or not religious, you don’t need any special philosophy to encourage you to give. I mean, of course, there are reasons that encourage us, but giving is part of being a human being, isn’t it? Because we live in a world and we’re always sharing resources. If you talk about the giving of wealth, the giving of protection, the giving of the Dharma. All of these, especially the giving of wealth or possessions, and the giving of protection, those things come very naturally to people. At least the people we care about. Whereas ethical conduct–refraining from harming others–for some people might be more difficult, because the afflictions arise so easily.

Anyway, it’s interesting, spend some time and see if you can think of reasons why one or the other comes first. And then what about learning? After faith, shouldn’t you learn? Or should you have ethical conduct first, get your act together and stop being a jerk, and then learn? And maybe giving comes before learning because we have to accumulate merit, also, in order to learn. But it would seem like learning should come very soon. Because you learn to give, you learn to practice ethical conduct. Think about it. And see what kind of order makes sense to you. Like I said, faith at the beginning and wisdom at the end, that kind of makes sense. And those are the two things that Nagarjuna points out are so important for the higher rebirth and the highest good–having a good rebirth (higher rebirth), and wisdom (highest good). Which means liberation and full awakening. Some people translate that as definite goodness. That term doesn’t do a lot for me.

To talk about generosity. Like I said, in one way it’s something people do very automatically. Since we were born, we were welcomed into the world with generosity. They fed us. Isn’t that generosity? They changed our diaper. They gave us vaccinations. They taught us how to speak, and read, and write. Gave us clothes, a blankie, and all those kinds of things. Right from the very beginning we’ve been a recipient of generosity.

But generosity here is for us to practice generosity. We’ve been the recipient of tremendous generosity, but have we reciprocated the generosity? That’s the question. What interferes with generosity? Attachment and miserliness. The idea “this is mine.” You can see what impedes generosity is a very strong feeling of “I” and “mine.” There’s an “I” and I possess things, and going into self-centered mind, “My happiness is more important than yours, so I’m going to keep it and I’m not going to give it to you.” If it’s something good. If it’s something I don’t need and I want to get rid of it, you can have it. But otherwise, look out for ourselves first. That comes as a big impediment to generosity.

Also to look at that feeling of fear that can sometimes lie behind generosity. The fear that if I give it I won’t have it, and I might need it someday. There are people who hoard stuff in their homes, when they pass away it’s very difficult for people even to get in their place because it’s so chock-a-block full with things. In my travels I stay at a lot of places. I stayed at one home like that. It was amazing. There were old newspapers from other countries stacked from the floor up. And all sorts of stuff. I couldn’t imagine what the person was going to do with all of that. But it definitely wasn’t going to get thrown out.

But of course, I save bottles and little boxes, because I am certain I’m going to need them. Who else saves bottles and boxes? Oh I have some companions. I only save little bottles and boxes, not the big ones. But I stayed at one person’s house who saved the big ones, and her whole basement was filled with empty cardboard boxes. If you ever needed to move, she had plenty of them there. I only save the little ones. I’m more economical, but if you want to move, I can’t help you.

We all have these ridiculous things that we hang on to out of fear that if I give it I will need it and I won’t have it. As if, if I give up one of my little boxes or things like that, then the next time when I go to travel and I have to pack my vitamins, I won’t have a container to put them in. And that’s actually happened. So you see, I have a reason for hanging onto my empty vitamin bottles. But I’m getting better. I’m learning to recycle them. I only save a certain number of them for the next trip, knowing that after that trip there will be a break where I can collect some more. But I will not wait until the last minute to get my empty vitamin bottles, because there may not be any.

Some people do it with robes. I remember staying at one monastery and one nun took me into her room, and her room, there was nothing on top of the cupboards, nothing on top of the desk. It was so spic and span. But for one reason or another she wanted to show me the inside of her cupboards…. So full of stuff. So full of stuff. Many people it’s with robes. You have four or five shemdaps, how many winter jackets do you have? How many zhens. How many dhonkas? And they have so many things. And long sleeved shirts, and short sleeved. And you need to go out and work in the forest, so you have four or five pairs of pants. And your different hats. And we gt. a lot of socks as gifts here. Do you have a lot of socks in your sock drawer? (Some people are looking a little guilty.)

We may all have different areas of things. Food is another one, and that one’s hard, living in a monastery, because we can’t keep food in our rooms. There are certain areas that are designated for sangha food, and your food has to be there at night, you can’t keep it in your room. But that’s hard. Don’t you just want to save something? You didn’t eat at dinner, so we want to save it for breakfast, so you take it to your room, or you put it inside your bowl where nobody will see it. Or you accidentally forget it at the side of your bowl. Hanging on to food. And when I travel, I always travel with food, because it happens that sometimes people don’t feed you. You arrive at a place and they expect you to have eaten on the plane, and the planes don’t serve food. So you see, I have reasons, important reasons to hang onto things.

Here I’m pretty much just talking about material possessions and wealth, but the reason for why we can’t give, and how difficult it can be. And sometimes also how difficult it is to accept gifts from other people.

I’ve done discussion groups and retreats, sometimes when we talk about generosity, and the generosity of accepting somebody else’s gift. Because sometimes somebody wants to give us something, and we just go “no no no,” And it’s very interesting to look at our mind. Why don’t we want to accept it? Do we think we’re too good for that kind of thing? Is it because we will feel obliged to that person afterwards? They gave us something, now we’re obliged to do something or give them something back, so we don’t want to accept the gift. Is it because we feel unworthy? “Oh, I’m not a good practitioner, I’m not a good person, they shouldn’t give me gifts.” Do you see how all those reasons are actually quite self-centered? “I don’t want to feel obliged. I don’t feel worthy.” These kinds of things. But we’re not thinking about the other person. If we thought about the other person, first of all we’d realize that it may hurt their feelings that we don’t want to accept their gift. And second of all, we’re denying them the opportunity to create merit, because of all of our ego conflict that leads us to say, “No, no, I won’t accept it.” And that’s not very kind for somebody who wants to create merit, for us to deny them that merit by not accepting their gift.

Of course, if we think they’re going to be poor afterwards, and that they really need what it is that they’re offering, then what I do in those cases is I accept the item, and right away I say to them, “And I want to offer it back.” Because that way you create merit by giving it to me, and I create merit by giving it to you. Because that lets the person know that I accepted their gift and I value that, but it also…I can see sometimes that people, they need this. Or it’s something that’s very precious to them. More precious to them than to me, and it’s better if they keep it. So accepting it, but giving it back, so that we both create merit.

That’s the first kind of generosity, of material things. We’ll talk about the other kinds next time.

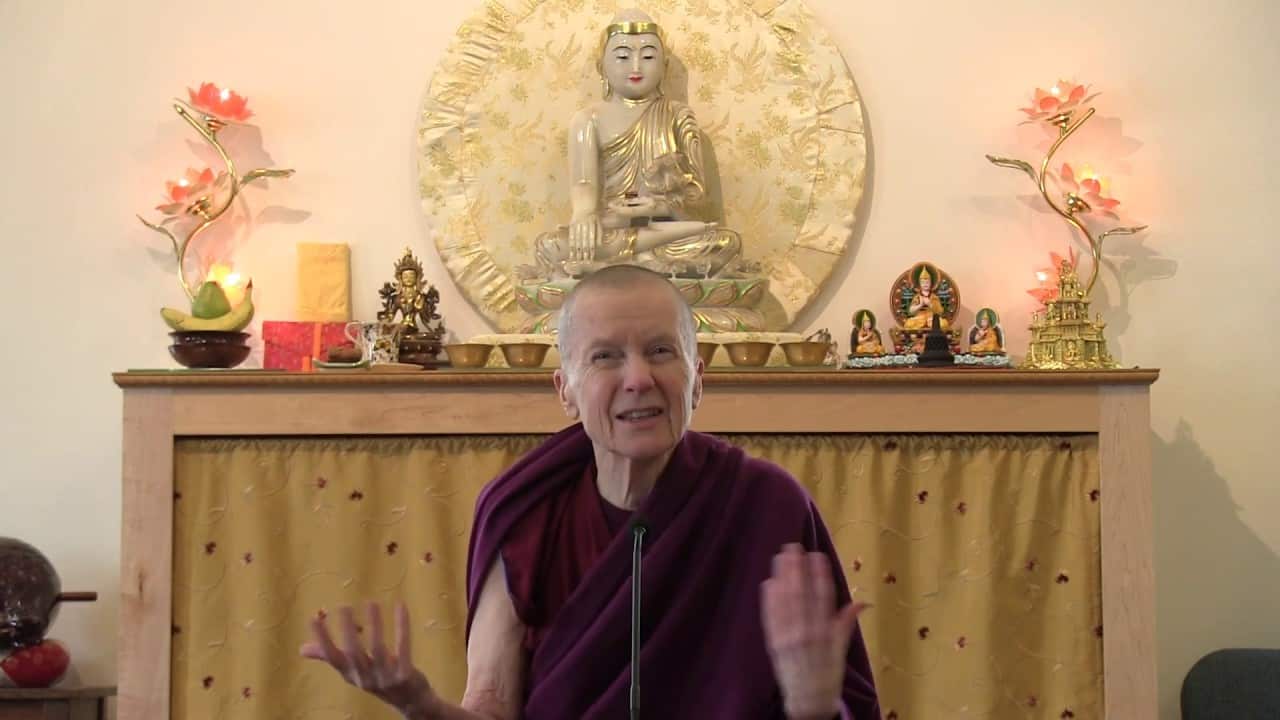

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.