Becoming a nun

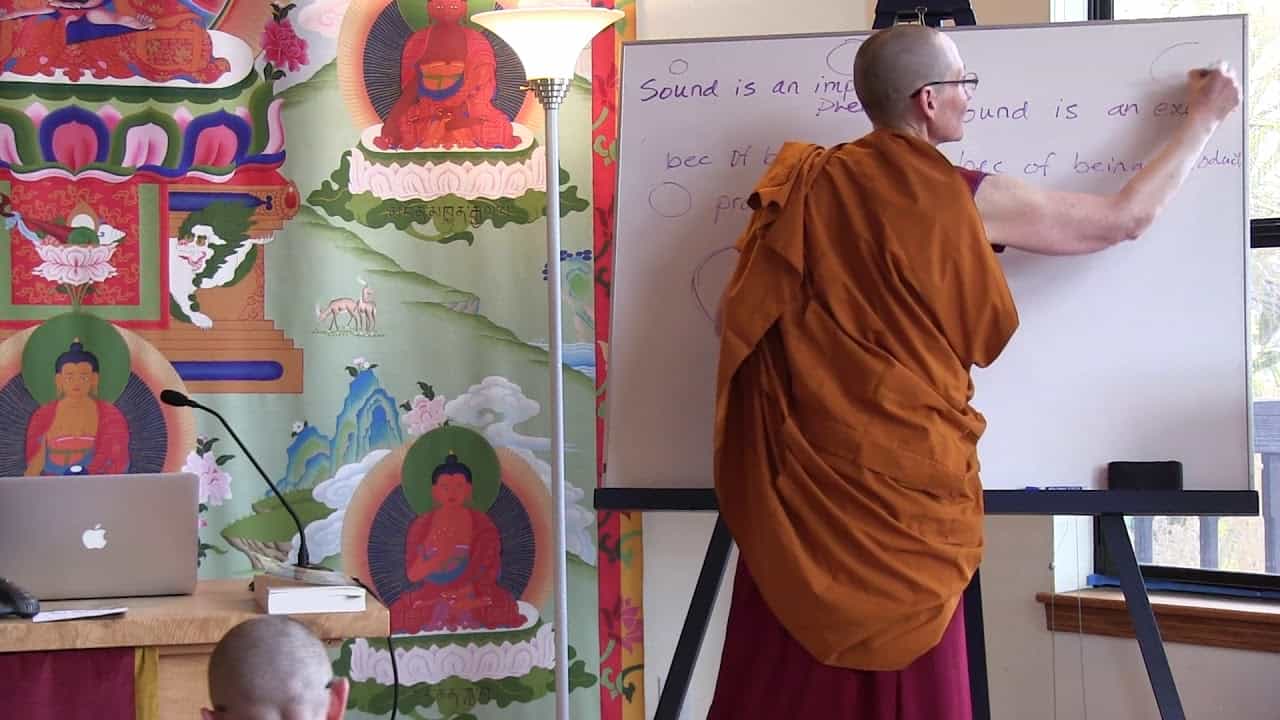

Venerable Semkye answers a question about joining the monastic tradition.

I would love to dedicate my life to teaching Buddhism and become a Buddhist nun. Why is it so expensive to do this and is there any help?

Thanks for your question. I rejoice at your enthusiasm and interest to ask. How I respond is dependent on your background and your Buddhist practice. Since I don’t know either, I will answer generally, by sharing what I have learned being a monastic in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition in the West, and living as a member of a monastic community.

Ordaining as a Buddhist monastic comes from a deep spiritual call; not a common one like most things we do in our lives. In many ways, ordained life is going “against the stream” of what general society qualifies as a successful life. By choosing the “homeless life,” as it is referred to, you are leaving behind many things that, in our world, mark you as a contributing and productive member of society. By choosing this life, you voluntarily leave behind many worldly concerns and experiences. Some of these worldly concerns include cutting the strong emotional ties of family and friends in exchange for cultivating the thought that all beings are family and friends. You will let go of most of your personal possessions in exchange for a life that nourishes inner wealth. Many forms of entertainment will be replaced with hearing, thinking, and meditating on the Buddha’s teachings and integrating them into your life. So, in a funny way, this is the “expensive” part—letting go of your worldly attachments, which may appear to you quite a large cost.

However, your motivation is the most crucial part of deciding to join the ordained Buddhist sangha. Wishing to cultivate the determination to be free from this cycle of birth, aging, sickness and death, as well as to be free of the afflictions and karma that bring this cycle, must be foremost. Hoping to teach Buddhism does not require becoming a monastic, since there are many good lay Buddhist teachers at Buddhist centers and at universities. Needless to say, transforming one’s mind is a full time job that requires our undivided attention. Generally, it is only after many years of inner spiritual work and a solid foundation in the Buddha’s teachings that the possibility of teaching arises.

As far as the expense of being ordained, the criteria used at Sravasti Abbey, where I live and train, is pretty straight forward. After going through an extensive probation period in which you and the community see if monastic life is a good fit for you, you must come to the Abbey debt-free. Abbey monastics may keep their personal funds, but there are restrictions on how we can use it.

Sravasti Abbey has a unique situation where the community is sustained by the kindness of many people all over the world in regards to food, clothing, medicine and shelter. Therefore our lifestyle is simple and everything at the Abbey, with the exception of a few personal items, is considered to belong to all the monastics or the “sangha” of the 10 directions.

As for other monastics, who do not to live in community, I am not as familiar with their decision-making process as far as where they will live their ordained life. Because many live on their own, they have expenses similar to lay people—paying rent, owning a car, buying their own food. Sometimes monastics hold jobs and get salaries, either in Dharma centers, universities, or in regular businesses. Western culture in general has not yet made the leap to support Buddhist monastics, and so those nuns not in community must make ends meet however they can.

I am curious why you think becoming a nun is expensive. If a teacher asks you to make a large donation or pay a fee money to ordain, something is wrong. However, if someone wants to ordain in order to have a place to live and food to eat, they do not have the proper motivation to become a monastic.

There are important questions to ask yourself and issues to ponder deeply if you are considering ordination. There are external as well as internal processes that require honesty, fortitude, and joyous effort. This is not something you decide in a few days or even months. As with all things, if you want certain results, you must commit to creating the correct causes and conditions for that result to happen.

You can find wise and excellent advice and teachings for those considering ordination on the this web site. This link will get you there. May it provide some clarity and answer some of your questions in more detail. You are also welcome to visit Sravasti Abbey to experience the monastic lifestyle directly and ask your questions in person. We welcome visitors! Just register ahead.

Venerable Thubten Semkye

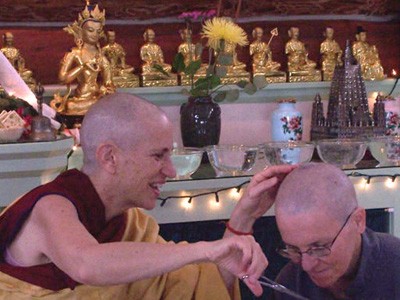

Ven. Semkye was the Abbey's first lay resident, coming to help Venerable Chodron with the gardens and land management in the spring of 2004. She became the Abbey's third nun in 2007 and received bhikshuni ordination in Taiwan in 2010. She met Venerable Chodron at the Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle in 1996. She took refuge in 1999. When the land was acquired for the Abbey in 2003, Ven. Semye coordinated volunteers for the initial move-in and early remodeling. A founder of Friends of Sravasti Abbey, she accepted the position of chairperson to provide the Four Requisites for the monastic community. Realizing that was a difficult task to do from 350 miles away, she moved to the Abbey in spring of 2004. Although she didn't originally see ordination in her future, after the 2006 Chenrezig retreat when she spent half of her meditation time reflecting on death and impermanence, Ven. Semkye realized that ordaining would be the wisest, most compassionate use of her life. View pictures of her ordination. Ven. Semkye draws on her extensive experience in landscaping and horticulture to manage the Abbey's forests and gardens. She oversees "Offering Volunteer Service Weekends" during which volunteers help with construction, gardening, and forest stewardship.