Dependent arising: a universal principle

At the teachings on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment by Je Tsongkhapa in Mundgod, India in December 2012, His Holiness the Dalai Lama highlighted that the principle of dependent arising is one of the distinguishing features of the Buddhadharma. According to this principle, although the people and things around us appear to be external objects that exist inherently and independently, in reality, all phenomena arise in dependence (i) on causes and conditions; (ii) on parts; and (iii) on being labeled and conceptualized by the mind. His Holiness expressed his wish for all beings, regardless of their faith, to study this universal principle of dependent arising, which could contribute to improvements in diverse fields such as environmental conservation, international relations and healthcare.

I was struck by His Holiness’ statement, because I first encountered teachings on the principle of dependent arising not in a Dharma class, but in two courses that I took in the Anthropology department at Princeton University. The first was a course on medical anthropology, a field that takes first-person narratives of the experience of illness as the starting point to study the complexities of healthcare management systems. One of the key concepts that our professor drove home was that illness is not an a priori phenomenon experienced solely by an individual—it is defined, understood and managed within a social and cultural context, and has broader effects on the patient’s family and society at large.

The social and cultural dimensions of illness

One of the key texts we read in the course was The Spirit Falls Down and Catches You by Anne Fadiman, which chronicled a Hmong immigrant family’s encounter with Western medical science as they sought a cure for their young daughter who is beset with seizures. American doctors diagnosed the child as an epileptic and did their best to treat her, but her parents refused to administer Western drugs that they did not trust, resulting in child protection services stepping in to remove their daughter from their care. After numerous trips to the hospital, the girl ended up in a vegetative state for life. The book thus asks whether Western medical science has indeed brought improvements to the Hmong family’s lives, or whether the child might have been better off in a traditional Hmong community, where she would have been revered as a shaman, and probably died a natural death at a young age.

Aside from highlighting the need to address myriad causes and conditions when treating an individual’s illness, such as family and culture, the story of the Hmong family also demonstrates how different cultures place different labels on the same set of symptoms manifested by the body. This ultimately creates very different results in terms of how those symptoms are experienced and treated. To me, this is a clear example of the Middle Way view of how phenomena are empty of inherent existence because they arise dependent on causes and conditions and are merely labeled by the mind, yet they still function on the conventional level. The field of medical anthropology does not deny that mental and physical experiences of illness exist, but it examines how different cultures conceive of and respond to those experiences. In particular, it questions whether Western medical science, which many of us in the developed world take for granted, indeed offers the best solutions regarding how to manage illness and the process of dying.

Practical applications of dependent arising in healthcare

By applying the principle of dependent arising to the study of healthcare, medical anthropologists have made the delivery of public healthcare more effective, and addressed ethical grey areas in contemporary medical science. Partners in Health, a non-profit organization founded by medical doctor and anthropologist Dr. Paul Farmer, has successfully brought cures for AIDS and tuberculosis to the developing world because it works closely with local communities, defying assumptions that the poor cannot manage treatment for chronic diseases. Organs Watch, an organization founded by anthropologist Dr. Nancy Scheper-Hughes, studies and monitors the global trafficking of human organs, as poor people in developing countries are enticed into selling their organs for a quick buck, only to have long-term health problems that they cannot manage. As Western medical science becomes globalized, corporatized and increasingly profit-oriented, the field of medical anthropology calls attention to the underlying structures of power that prevent equal access to proper healthcare in different societies, and questions whether it is ethical for humanity to perpetuate such systems.

Deconstructing the world

The other anthropology course that left a strong impact on my mind applied the principle of dependent arising to the field of global politics. Entitled “Globalization and ‘Asia,'” the course traced how globalization, which appears to be a contemporary phenomenon, actually has its roots in colonialism that began more than a century ago. The course also challenged the labels that we place on different parts of the world and take for granted. For instance, our professor highlighted how the landmass we now call “Asia” is a construct of colonial history, as it is a conglomerate of vastly different countries with little in common, except for the fact that they are “not Europe.” We also examined how the label “the West” can be employed fluidly depending on the context—for example, Japan might be referred to as being part of “the West” as a modern, developed nation, but can also be referred to as part of “Asia” because of its cultural heritage.

Going further, the course took apart the labels we place on different parts of the world based on the theory of material progress and development that there is a “First World,” “Second World” and “Third World.” It challenged the underlying assumption that all nations are supposed to move towards “First World” status based on certain material indicators. Our professor pointed out that these labels did not arise independently, but have their roots in colonial history, where one part of the world became enriched based on the oppression of another. The course further questioned what “First World” nations defined to be “universal human rights” and how these could sometimes be a pretext to justify war against a less developed country, in the same way that colonial powers claimed to be civilizing barbaric natives when carrying out conquests to advance their own economic interests. By pointing out the historical context behind the contemporary global imbalance in the distribution of power and economic resources, the course made me re-think how I perceive of the world and the assumptions I make about what constitutes “progress” for a society and culture.

Deconstructing the self

Interestingly, taking these two courses primed my mind such that when I first heard teachings on dependent arising at a workshop on the Heart Sutra, they made perfect sense. What I found astounding was the Buddha’s teaching that this principle applies not only to specific phenomena, like illness or global politics, but to all phenomena. Even more mind-blowing to me is the teaching that what we call the self, which is dependent on this body and mind we cherish so dearly, is also a dependently arisen phenomenon, arising dependent on causes and conditions, parts, and is merely labeled and conceived of by the mind. I am still wrapping my head around seeing the self as dependently arisen, but certainly, from the courses I have taken at college, I believe we would do well to follow His Holiness’ advice, and apply our understanding of the centuries-old principle of dependent arising to the study of contemporary fields of knowledge.

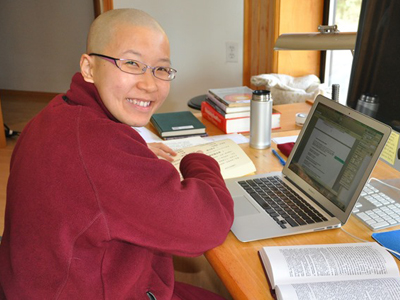

Venerable Thubten Damcho

Ven. Damcho (Ruby Xuequn Pan) met the Dharma through the Buddhist Students’ Group at Princeton University. After graduating in 2006, she returned to Singapore and took refuge at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See (KMSPKS) Monastery in 2007, where she served as a Sunday School teacher. Struck by the aspiration to ordain, she attended a novitiate retreat in the Theravada tradition in 2007, and attended an 8-Precepts retreat in Bodhgaya and a Nyung Ne retreat in Kathmandu in 2008. Inspired after meeting Ven. Chodron in Singapore in 2008 and attending the one-month course at Kopan Monastery in 2009, Ven. Damcho visited Sravasti Abbey for 2 weeks in 2010. She was shocked to discover that monastics did not live in blissful retreat, but worked extremely hard! Confused about her aspirations, she took refuge in her job in the Singapore civil service, where she served as a high school English teacher and a public policy analyst. Offering service as Ven. Chodron’s attendant in Indonesia in 2012 was a wake-up call. After attending the Exploring Monastic Life Program, Ven. Damcho quickly moved to the Abbey to train as an Anagarika in December 2012. She ordained on October 2, 2013 and is the Abbey’s current video manager. Ven. Damcho also manages Ven. Chodron’s schedule and website, helps with editing and publicity for Venerable’s books, and supports the care of the forest and vegetable garden.