Exploring the Buddha’s teachings

Introduction to the Buddhist worldview

To begin exploring the Buddha’s teachings, it’s helpful to understand a little about the situation we are in, which is called “cyclic existence” (or “samsara” in Sanskrit). Having a general understanding about cyclic existence, its causes, nirvana as an alternative, and the path to peace will enable us to appreciate other Dharma teachings.

If we aspire for liberation and enlightenment, we need to know from what we want to be liberated. Thus, it is necessary to understand our present situation and what causes it. This is crucial for any deep spiritual practice. Otherwise, it is very easy for our spiritual practice to be hijacked by attachment and anxiety about things that do not have great meaning in the long run. Our thoughts are so easily distracted to worrying about relatives and friends, harming our enemies, promoting ourselves, fearing the aging process, and a myriad of other concerns that center around our own happiness in only this life. However, when we’re aware of what cyclic existence is and develop a sincere wish to be free from it—that is, to renounce samsara’s unsatisfactory circumstances and their causes—the motivation for our spiritual practice becomes quite pure.

Cyclic existence

What is cyclic existence, or samsara? Firstly, it is being in the situation where, again and again, we take rebirth under the influence of ignorance, afflictions, and karma. Cyclic existence is also the five psychophysical aggregates that we live with right now, that is, our

- body;

- feelings of happiness, unhappiness, and indifference;

- discriminations of objects and their attributes;

- emotions, attitudes, and other mental factors; and

- consciousnesses—the five sense consciousnesses which know sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations, and the mental consciousness which thinks, meditates, and so forth.

In short, the basis—our body and mind—upon which we label “I” is cyclic existence. Cyclic existence doesn’t mean this world. This distinction is important because otherwise we may mistakenly think, “Renouncing cyclic existence is to escape from the world and go to nevernever land.” However, according to the Buddha, this way of thinking is not renunciation. Renunciation is about renouncing suffering or unsatisfactory circumstances and their causes. In other words, we want to relinquish clinging to a body and mind that are produced under the influence of ignorance, mental afflictions, and karma.

Our body

We all have a body. Did you ever stop to wonder why we have a body and why we identify so strongly with our body? Have you ever wondered if there are alternatives to having a body that gets old, sick, and dies? We live in the midst of a consumer society in which the body is seen as a wonderful thing. We are encouraged to spend as much money as possible to satisfy the wants, needs, and pleasures of this body.

We are socialized to regard our body in certain ways, often according to its physical characteristics. As a result, a great deal of our identity depends on the color of the body’s skin, the body’s reproductive organs, and the age of this body. Our identity is bound up with this body. In addition, much of what we do on a daily basis concerns beautifying and giving pleasure to this body. How much time do we spend on such activities? Men and women alike can spend a long time looking in the mirror and worrying about how they look. We’re concerned about our appearance and whether others find us attractive. We don’t want to appear unkempt. We’re concerned about our weight, so we watch what we eat. We’re concerned about our image, so we think about the clothes we wear. We think about what portions of our body to hide and what parts to show off or reveal. Concerned about having grey hair, we dye it. Even if we are young and our hair isn’t grey yet, we want our hair to be another color—sometimes even pink or blue! We worry about having wrinkles, so we use anti-aging skin care or receive Botox treatments. We make sure that our glasses are the stylish type that everyone is wearing and that our clothes conform to the current fashion. We go to the gym, not only to make our body healthy, but also to sculpt it into what we think other people think our body should look like. We mull over restaurant menus when we dine out, pondering which dish will give us the most pleasure. But then we worry that it’s too fattening!

Have you ever thought about how much time people spend talking about food? When we go to a restaurant, we spend time pondering the menu, asking our friend what he or she will have, and questioning the wait staff about the ingredients and which dish is better. When the food arrives, we’re talking with our friend about other things so we don’t taste each bite. After we finish eating, we discuss whether the meal was good or bad, too spicy or not spicy enough, too hot or too cold.

We are so focused on giving this body pleasure. The mattress we sleep on must be just right, not too hard and not too soft. We want our house or our workplace at the right temperature. If the temperature is too cold, we complain. If it’s too hot, we complain. Even our car seats have to be exactly as we like them. Nowadays, in some cars, the driver’s seat and the passenger’s seat have different heating elements so the person sitting next to you can be at 68°F, and you can be at 72°F. Once I was in a car where I experienced a strange feeling of heat below me and wondered if something was wrong with the car. I asked my friend who explained that individualized heating in each seat was the latest feature. This example shows how much we seek even the tiniest pleasure.

We put so much time and energy into trying to make our body comfortable all the time. And yet, what is this body actually? Depending upon our perspective, the body can be considered in varying ways, according to biological, chemical, and physical models. Of course, the physical reduction of our body into component pieces can continue indefinitely; a fundamental or essential unit cannot be established, theoretically or otherwise. Eventually, and at greatly reduced levels, the solidity of the substances of the body itself is called into question. Is the body mostly substance or space? At the atomic level, one finds that it is mostly space. When we investigate deeply, what is the actual nature of this body that we hold to be so solid, that we cling to, that we perceive as “I” or “mine”? It is a myriad of reducible substances that comprise a certain amount of space and function at a variety of levels. That’s all our body is. In other words, it is a dependently-arising phenomenon.

The reality of our body

What does the body do? First, it is born, which can be a difficult process. Of course, most parents look forward to having a baby. However, labor is so called for a reason—having a baby is hard work. The birthing process is hard on the baby too. He or she is squeezed out and then welcomed into the world with a whack on the bottom and drops in the eyes. Not understanding the situation, the baby wails even though the doctor and nurse are acting out of compassion.

Aging begins the moment after we are conceived in our mother’s womb. Although our society idolizes youth, no one is staying young. Everyone is aging. How do we view aging? We can’t stop the aging process. Do we know how to age gracefully? Do we have the skill to work with our mind as it finds itself in an aging body? The Dharma can help us have a happy mind as we age, but we’re often too busy enjoying sense pleasures to practice it. Then when our body is old and cannot enjoy sense pleasures as much, our mind becomes depressed and life seems purposeless. How sad it is that so many people feel that way!

Our body also gets sick. This, too, is a natural process. No one likes illnesses, but our body does fall ill anyway. In addition, our body is usually uncomfortable in one way or another. After birth, aging, and illness, what happens? Death. Although death is the natural result of having a body, it is not something we look forward to. However, there’s no way to avoid death.

Another way of understanding the body relates to its by-products. Our body is basically an excretion factory. We do so much to clean our body. Why? Because our body is dirty all the time. What does it make? It makes feces, urine, sweat, bad breath, ear wax, mucus, and so forth. Our body doesn’t emanate perfume, does it? This is the body we adore and treasure, the body we try so hard to make look good.

This is the situation we’re in. It’s uncomfortable to think about this so we try to avoid looking at this reality. For example, no one likes to go to cemeteries. In the U.S., cemeteries are designed to be beautiful places. They are landscaped with green grass and beautiful flowers. In one such cemetery in California there is an art museum and park, so you can go to the cemetery for a picnic on Sunday afternoon and look at art. In that way, you will avoid remembering that cemeteries are where we put dead bodies.

When people die, we put makeup on them so they look better than when they were alive. When I was in college, my friend’s mother died and I went to her funeral. She had been ill for a long time with cancer and was emaciated. The morticians did such a good job of embalming her that people at the funeral commented that she looked better than they had seen her look in a long time! We ignore death so much that we don’t know how to explain it to our children. Often we tell children that their dead relatives went to sleep for a long time, because we don’t understand what death is. Death is too scary for us to think about and too mysterious to explain.

We do not enjoy these natural processes that our bodies go through, so we do our best to avoid thinking about them or having them happen. Yet, such experiences are definite once we have a body. Think about this: Do I want to continue living in this state—a state where I am born with this type of body? We may say, “Well, if I’m not born with this kind of body, I won’t be alive.” That leads to another can of worms. What does it mean to be alive? Who is this “I” who thinks it’s alive? Also, if our current life is not completely satisfactory, what kind of life will afford us greater satisfaction??

The unsatisfactory nature of the mind and our existence

Our aging body that falls ill and our confused mind are unsatisfactory in nature. That’s the meaning of dukkha—a Sanskrit term that is often translated as “suffering,” but actually means “unsatisfactory in nature.”

Although our body does bring us some pleasure, the situation of having a body under the influence of ignorance and karma is unsatisfactory. Why? Because our current body cannot give us lasting or secure happiness or peace. Similarly, an ignorant mind is unsatisfactory in nature.

Our mind has the Buddha nature, but right now that Buddha nature is obscured and our mind is confused by ignorance, attachment, anger, and other disturbing emotions and distorted views. For example, we try to think clearly and we fall asleep. We get confused when we try to make decisions. We aren’t clear what criteria to use to make wise choices. We’re not clear about how to distinguish between constructive and destructive actions. We sit down to meditate and our mind bounces all over the place. We can’t take two or three breaths without the mind getting distracted or drowsy. What distracts our mind? By and large, we’re running after objects that we’re attached to. Or we are planning how to destroy or get away from things we don’t like. We sit to meditate and plan the future instead—where we’ll go on holiday, what movie we want to see with our friend, and so forth. Or we are distracted by the past and rerun events from our lives again and again. Sometimes, we try to rewrite our own history, while other times we get stuck in the past and feel hopeless or resentful. None of this makes us happy or brings us fulfillment, does it?

Do we want to be born, again and again, under the influence of ignorance, afflictions, and polluted karma which make us take a body and mind which are unsatisfactory in nature? Or do we want to see if there is a way to free ourselves from this situation? If so, we must consider other types of existence—those in which we aren’t attached to a body and mind that are under the influence of afflictions and karma. Is it possible to have a pure body and pure mind that are free of ignorance, mental afflictions, and the karma that causes rebirth? If so, what is that state and how can we attain it?

Spend some time thinking about this. Look at your current situation and ask yourself whether you want it to continue. If you don’t want it to continue, is it possible to change? And if it’s possible to change, how do you do it? These questions are the topic of the Buddha’s first teaching—the four noble truths.

Ignorance: the root of all suffering

Having understood that the situation of cyclic existence is unsatisfactory, we explore the causes from which it originates: ignorance, mental afflictions, and the karma they produce. Ignorance is the mental factor that misunderstands how things exist. It’s not simply obscuration about the ultimate nature. Rather, ignorance actively misapprehends the ultimate mode of existence. Whereas persons and phenomena exist dependently, ignorance grasps them as having their own inherent essence, existing from their own side and under their own power. Due to beginningless latencies of ignorance, persons and phenomena appear inherently existent to us, and ignorance actively grasps the mistaken appearance to be true.

While we grasp at the inherent existence of all phenomena, let’s investigate our self, the “I,” in particular because this grasping is the worst troublemaker. In relation to our body and mind—what we call “I”—there appears to be a very solid and real person or self or “I” there. Ignorance believes such an inherently existent person to exist as it appears. While such an inherently existent “I” does not exist at all, ignorance grasps it as existent.

Does this mean there is no “I” at all? No. The conventional “I” exists. All persons and phenomena exist by merely being labeled in dependence upon the body and mind. However, ignorance doesn’t understand that the “I” is just dependently existent and instead constructs this big ME that exists independent of everything. This independent “I” seems so real to us even though it doesn’t exist in that way at all. This big ME is the center of our universe. We do everything to give it what it desires, to protect and take care of it. Fear that something bad will happen to ME fills our mind. Craving for what will give ME pleasure prevents us from seeing things clearly. Comparing this real “I” to others causes stress.

The way we think we exist—who the “I” is—is a hallucination. We think and feel there’s this big “I” there. “I want to be happy. I am the center of the universe. I, I, I.” But what is this “I” or self that we predicate everything on? Does it exist the way it appears to us? When we start to investigate and scratch the surface, we see that it does not. A real Self or Soul appears to exist. However, when we search for what exactly it is, instead of becoming clear, it becomes more nebulous. When we search for something that actually is a solid “I” everywhere in our body and mind and even separate from our body and mind, we can’t find what this “I” is anywhere. The only conclusion at this point is to acknowledge that a solid, independent self does not exist.

We have to be careful here. While the inherently existent “I” that we grasp as existent does not exist, the conventional “I” does. The conventional “I” is the self that exists nominally, by being merely designated in dependence upon the body and mind. Such an “I” appears and functions, but it is not an independent entity that stands on its own, under its own power.

By seeing that there is no inherent existence in either persons or phenomena and by repeatedly familiarizing ourselves with this understanding, this wisdom will gradually eliminate the ignorance that grasps at inherent existence as well as the seeds and latencies of ignorance. When we generate the wisdom that understands reality—the emptiness of inherent existence—the ignorance that sees the opposite of reality is automatically overpowered. When we understand things as they are, the ignorance that misapprehends them gets left by the wayside.

In this way ignorance is eliminated from the root so that it can never reappear. When ignorance ceases, the mental afflictions which are born from it also are cut off; just as the branches of a tree collapse when the tree is uprooted. Thus the karma produced by the afflictions ceases to be created and, as a result, the dukkha of cyclic existence stops. In brief, cutting off ignorance extinguishes afflictions. By eliminating the afflictions, the creation and ripening of karma that brings rebirth in cyclic existence come to an end. When rebirth ceases, dukkha does as well. Therefore, the wisdom realizing emptiness is the true path that leads us out of dukkha.

To generate the energy to practice the path leading to nirvana we must first be acutely aware of the unsatisfactory nature of cyclic existence. Here it becomes obvious that the Buddha did not talk about suffering so that we would become depressed. Feeling depressed is useless. The reason for thinking about our situation and its causes is so we will do something constructive to free ourselves from it. It’s very important to think about and understand this point. If we’re not aware of what it means to be under the influence of afflictions and karma, if we don’t understand the ramifications of having a body and mind that are under the control of ignorance and afflictions, then we will give way to indifference and do nothing to improve our situation. The tragedy of such indifference and unknowing is that suffering does not stop at death. Cyclic existence continues with our future lives. This is very serious. We need to pay attention to what the Buddha said so that we don’t find ourselves in an unfortunate rebirth in the next life, a life in which there’s no opportunity to learn and practice the Dharma.

If we ignore the fact that we’re in cyclic existence and immerse ourselves in trying to be happy in this life by seeking money and possessions, praise and approval, good reputation, and sense pleasure and by avoiding their opposites, what will happen when we die? We’ll be reborn. After that rebirth, we’ll take another life and another and another, all under the control of ignorance, afflictions, and karma. We’ve been doing this since beginningless time. For this reason, it’s said we’ve done everything and been everything in cyclic existence. We’ve been born in the realms of highest pleasure and realms of great torment and everything in between. We’ve done this countless times, but for what purpose? Where has it gotten us? Do we want to continue living like this endlessly in the future?

When we see the reality of cyclic existence, something inside shakes us, and we become afraid. This is a wisdom fear, not a panicked, freaked-out fear. It’s a wisdom fear because it sees clearly what our situation is. In addition, this wisdom knows there is an alternative to the continued misery of cyclic existence. We want genuine happiness, fulfillment, and peace that won’t disappear with changing conditions. This wisdom fear isn’t intended to just put a band-aid on our dukkha and make our body and mind comfortable again so that we can continue ignoring the situation. This wisdom fear says, “Unless I do something serious, I’m never going to be completely satisfied and content, make the best use of my human potential, or be genuinely happy. I don’t want to waste my life, so I’m going to practice the path to cease this dukkha and find secure peace, peace that will enable me to work for the benefit of sentient beings without being encumbered by my own limitations.”

Rebirth

Implicit in this explanation is the idea of rebirth. In other words, there isn’t just this one life. If there were just this one life, when we die, cyclic existence will be over. In that case, there would be no need to practice the path. But it’s not like that.

How did we get here? Our mind necessarily has a cause. It didn’t arise out of nothing. We say that our current mind is a continuation of the mind of the previous life. What happens when we die? The body and mind separate. The body is made of matter. It has its continuum and becomes a corpse, which further decomposes and is recycled in nature. The mind is clear and aware. The mind isn’t the brain—the brain is part of the body and is matter. The mind, on the other hand, is formless, not material in nature. It, too, has a continuum. The continuum of clarity and awareness goes on to another life.

The mind is all conscious aspects of ourselves. The presence or absence of consciousness is what differentiates a corpse from a living being. The continuity of our mind has existed beginninglessly and will continue to exist endlessly. Thus, we need to be concerned about the course that this continuum takes. Our happiness depends on what is going on in our mind. If our mind is contaminated by ignorance, the result is cyclic existence. If the mind is imbued with wisdom and compassion, the result is enlightenment.

Thus, it’s crucial to think about our situation in cyclic existence. One of the things that makes it so difficult for us to see our situation is that the appearance of this life is so strong. What appears to our senses seems so real, so urgent, and concrete that we can’t imagine anything else. Yet, everything that appears to exist with its own, true, and inherent nature does not exist in the way it appears. Things appear unchanging whereas they are in continual flux. What is in fact unsatisfactory by nature seems to be happiness. Things appear as independent entities, whereas they are dependent. Our mind is tricked and deceived by appearances. Believing false appearances to be true obscures us from seeing what cyclic existence really is and prevents us from cultivating the wisdom that frees us from it.

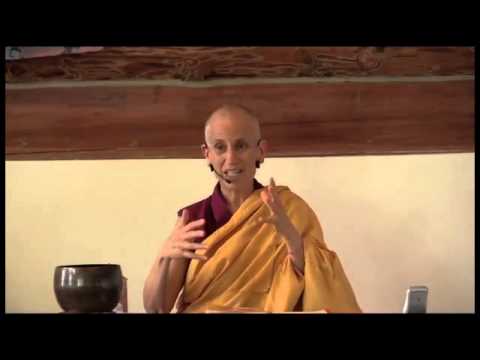

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.