The four distortions: Who do you think you are?

The four distortions: Who do you think you are?

A Bodhisattva’s Breakfast Corner talk on the Four Truths of the Aryas taught by Shakyamuni Buddha, also known as the Four Noble Truths.

We’ve been talking about conceptions and especially ones about impermanence: thinking that impermanent things are permanent, and thinking that things that do not have the ability to bring us lasting happiness do. Then, the most serious misconception, a deeply rooted misconception we have, is that things have a self. In other words, it’s thinking that they exist from their own side, independent of other things, and that they have some kind of essence or essential quality that makes them what they.

They say that all of our afflictions, all of the other wrong views, are based on this one. While we can sometimes notice that we’re grasping at impermanent things as permanent, or grasping at things that don’t have the ability to make us happy as making us lastingly happy, it is so hard to understand when we’re grasping at a self. Because things appear that way, we agree, and it seems reasonable.

And it all starts out with there being a real me. Why is there a real me? Because I feel it. Isn’t that a good reason? “I feel like there is me, so therefore I exist!” You don’t even have to think like Descartes did. [laughter] “Why do I exist: because I feel it.” There’s a me and just my feeling that there is a me is good enough. And we never question that. We never question that.

And yet when we examine and search for what exactly it is that we are—who is this me that I think I am—then it becomes extremely difficult to pinpoint something. If we say we are a body, then it means we should be able to identify one part of the body that is me. So, slice open the body: are you your brain? I went to an autopsy once. They took out the brain, put it on a scale, and weighed it. Were they weighing a person? Were they weighing that person? If your loved one’s brain were out there in front of you, would you say, “I love you so much!” You’d probably say, “Aiyeeeeee!” [laughter]

So then, are we one mental state? Are we our anger? Are we our love? Are we some kind of wise mental state hanging out in there? Well, if we are that one mental state, then what about all these other mental states? Are they not us?

Maybe we’re something that is independent of the body and mind altogether—some kind of soul. There’s a body and mind and plop, something else gets reborn in there. That can be a strong feeling, especially when you grew up with that kind of idea. And yet, then we have to ask, “What is that soul?” And, if it is independent of the body and mind, then why do we always assume a person is related with the body and the mind?

Well, we always know a person by identifying them with a body or a mind. So, if the soul is neither the body nor the mind, then what exactly is the soul? You can’t say the soul is what thinks because the mind is what thinks. You can’t say the soul is what feels because the mind is what feels. What exactly does the soul do that neither the body nor the mind do? And how does it relate to you? And how is it something personal?

When we look for this self that we assume we are, we have a very, very difficult time finding it. The reason for that is because the way we conceive the self to exist is not the way in which it exists. What we’re looking for doesn’t exist. There is a self, but it exists by being merely labeled. But you can’t find it when you look for it. It’s there when you don’t look. You can still say, “Yeah, Venerable Tarpa is there; Venerable Semkye is there.” You can look on a conventional level. But when you examine just exactly what this word refers to, you can’t find something and say, “That’s it; that’s who the person is.”

When we don’t examine and analyze, the person is kind of an abbreviation for that combination of body and mind. It’s a kind of short hand that says that particular body and mind is walking across the room! [laughter] Or maybe you say that body is walking across the room, but you have to add the mind in there because otherwise it would be a dead body. So, it becomes, “That body that is connected with mind is walking across the room.” That’s pretty long to say. It’s easier to just say, “Joe is walking across the room.”

It’s interesting when we have that feeling of me to try and research, “Just exactly what is that?” My mother used to ask me, “Who do you think you are?” That’s an excellent question! [laughter]

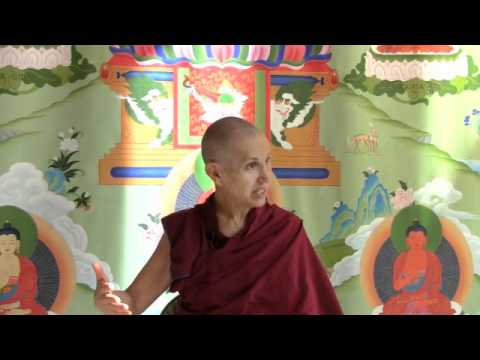

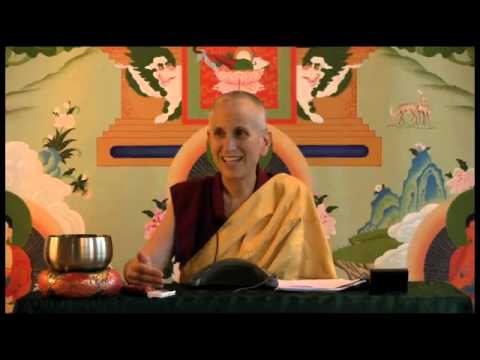

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.