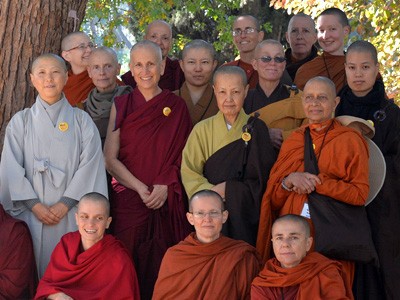

Western Buddhist nuns

A new phenomenon in an ancient tradition

Years ago at an interfaith conference in Europe, I was asked to speak about the lives of Western nuns. Thinking that people would not be interested in what was ordinary life for me, I instead gave a Dharma talk about how we trained our minds in love and compassion. Afterwards, several people came up to me and said, “Your talk was very nice, but we really wanted to hear about the lives of the Western nuns! How do you live? What are your problems and joys?” Sometimes it is difficult to discuss this: when speaking about the problems, there is the risk of complaining or of others thinking we are complaining; when speaking about the joys, there is the risk of being too buoyant or of others perceiving us as arrogant. In any case, let me say that I will speak in general statements from the viewpoint of being ordained in the Tibetan tradition—in other words, what is written here is not universal to all Western Buddhist nuns. And now I will plunge in and talk about the experiences of we Western nuns.

Plunge in … that’s what most of us did. The Dharma spoke deeply to our hearts, and so, counter to all expectations of our cultures and our families, we quit our jobs, parted from our dear ones, were ordained as Buddhist nuns and in many cases, went to live in other countries. Who would take such radical steps in order to practice the Dharma? How are we unlike the Asian women who are ordained?

In general, Asian women receive ordination when they are young, malleable girls with little life experience, or when their families are grown, they are elderly and seek life in a monastery for its spiritual and/or physical comforts. On the other hand, most Western nuns are ordained as adults. They are educated, have careers, and many have had families and children. They bring their talents and skills to the monastery, and they also bring their habits and expectations that have been well polished through years of interactions in the world. When Asian women are ordained, their families and communities support them. Becoming a nun is socially acceptable and respectable. In addition, Asian cultures focus more on group than individual identity, so it is comparatively easy for the newly-ordained to adapt to community life in a monastery. As children, they shared bedrooms with their siblings. They were taught to place the welfare of their family above their own and to respect and defer to their parents and teachers. Western nuns, on the other hand, grew up in a culture that stresses the individual over the group, and they therefore tend to be individualistic. Western women have to have strong personalities to become Buddhist nuns: their families reproach them for relinquishing a well-paying job and not having children; Western society brands them as parasites who don’t want to work because they are lazy; and Western culture accuses them of repressing their sexuality and avoiding intimate relationships. A Western woman who cares about what others think about her is not going to become a Buddhist nun. She is thus more likely to be self-sufficient and self-motivated. These qualities, while in general good, can be carried to an extreme, sometimes making it more difficult for these highly-individualistic nuns to live together in community.

That is, if there were a community to live in. As first generation Western Buddhist nuns, we indeed lead the homeless life. There are very few monasteries in the West, and if we want to stay in one, we generally have to pay to do so because the community has no money. That presents some challenges: how does someone with monastic precepts, which include wearing robes, shaving one’s head, not handling money, and not doing business, earn money?

Many Westerners assume that there is an umbrella institution, similar to the Catholic Church, that looks over us. This is not the case. Our Tibetan teachers do not provide for us financially and in many cases ask us to raise money to support their Tibetan monk disciples who are refugees in India. Some Western nuns have savings that are rapidly consumed, others have kind friends and family who sponsor them, and still others are forced by conditions to put on lay clothes and get a job in the city. This makes keeping the ordination precepts difficult and prevents them from studying and practicing intensely, which is the main purpose for which they were ordained.

How does one then receive monastic training and education? Some Western nuns opt to stay in Asia for as long as they can. But there too they face visa problems and language problems. Tibetan nunneries are generally overcrowded, and there is no room for foreigners unless one wants to pay to live in a guestroom. Tibetan nuns do rituals and receive teachings in the Tibetan language, their education beginning with memorizing texts. The majority of Western nuns, however, does not speak Tibetan and needs an English translation to receive teachings. In addition, memorizing texts in Tibetan is generally not meaningful to them. They seek to learn the meaning of the teachings and how to practice them. They want to learn meditation and to experience the Dharma. While the Tibetan nuns grew up with Buddhism in their families and culture since childhood, the Western nuns are learning a new faith and thus have different questions and issues. For example, while a Tibetan nun takes the existence of the Three Jewels for granted, a Western nuns wants to know exactly what the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha are and how to know they actually exist. Therefore, even in India, the Western nuns do not fit into the established Tibetan religious institutions.

Many Western nuns are sent to work in Dharma centers in the West, where they receive room, board, and a tiny stipend for personal needs in return for working for the center. Although here they can receive teachings in their own language, for the newly-ordained, life in Dharma centers can be difficult because they live amongst lay people. The curriculum in the center is designed for the lay students and the resident lama, if there is one, is usually too busy with the lay community to train the one or two Western monastics who live there.

Transforming difficulties into the path

Difficulties such as those described above are also challenges for practice. To remain a nun, a Western woman needs to implement the Buddha’s teachings in order to make her mind happy in whatever circumstances she finds herself. She has to meditate deeply on impermanence and death so that she can be comfortable with financial insecurity. She has to contemplate the disadvantages of attachment to the eight worldly concerns so that praise and blame from others do not affect her mind. She must reflect on karma and its effects to accept the difficulties she encounters in receiving an education. And she needs to generate the altruistic heart that wishes to remedy these situations so that others do not have to encounter them in the future. Thus, her difficulties are the catalyst for her practice, and through practice her mind is transformed and becomes peaceful.

One of the biggest challenges is to live as a celibate in the West, where sexuality spills from the soap boxes and the soap operas. How can one be emotionally happy when the media and societal values pronounce romantic relationships as the be-all of life? Again, practice is the secret. To keep our precepts, we have to look beyond superficial appearances; we have to understand deeply the ingrained emotional and sexual patterns of attachment that keep us imprisoned in cyclic existence. We must understand the nature of our emotions and learn to deal with them in constructive ways without depending on others to comfort us or make us feel good about ourselves.

People wonder if we see our families and our old friends and if we miss them. Buddhist nuns are not cloistered. We can visit our families and friends. We do not stop caring for others simply because we are ordained. However, we do try to transform the type of affection we have for them. For ordinary people in worldly life, affection leads to clinging attachment, an emotion that exaggerates the good qualities of someone and then wishes not to be separated from him or her. This attitude breeds partiality, wishing to help only our dear ones, harm the people we don’t like, and ignore the multitudes of beings we don’t know.

As monastics, we have to work strongly with this tendency, using the meditations on equanimity, love, compassion, and joy to expand our hearts so that we see all beings as lovable. The more we gradually train our mind in this way, the less we miss our dear ones and the more we feel close to all others simply because they are sentient beings who want happiness and do not want suffering as intensely as we do. This open-hearted feeling does not mean we don’t cherish our parents. To the contrary, the meditations on the kindness of our parents open our eyes to all that they did for us. However, rather than be attached only to them, we endeavor to extend the feeling of love to all others as well. Great internal satisfaction arises as we develop more equanimity and open our hearts to cherish all other beings. Here, too, we see what seems to be a difficulty—not living in close contact with our family and old friends—to be a factor that stimulates spiritual growth when we apply our Dharma practice to it.

Some conditions that may initially seem detrimental can also be advantageous. For example, Western nuns are not an integral part of the Tibetan religious establishment, whose hierarchy consists of Tibetan monks. Although this does have its disadvantages, it also has given us greater freedom in guiding our practice. For example, the bhikshuni or full ordination for women never spread to Tibet due to the difficulties of having the required number of bhikshunis travel across the Himalayan Mountains in previous centuries. The novice ordination for women does exist in the Tibetan tradition and is given by the monks. Although several Tibetan monks, including the Dalai Lama, approve of nuns in the Tibetan tradition receiving bhikshuni ordination from Chinese monastics, the Tibetan religious establishment has not officially sanctioned this. In recent years, several Western women have gone to receive the bhikshuni ordination in the Chinese and Vietnamese traditions where it is extant. Because they are part of the Tibetan community and more liable to its social pressure, it is much more difficult for Tibetan nuns to do this. In this way, not being an integral part of the system has its advantages for the Western nuns!

Receiving ordination

In order to receive ordination as a Buddhist nun, a woman must have a good general understanding of the Buddha’s teachings and a strong, stable motivation to be free from cyclic existence and attain liberation. Then she must request ordination from her teacher. In the Tibetan tradition, most teachers are monks, although some are lay men. There are very few women teachers in our tradition at present. If the teacher agrees, he will arrange the ordination ceremony, which in the case of the sramanerika or novice ordination, lasts a few hours. If a novice nun in the Tibetan tradition later wants to receive the bhikshuni ordination, she must find a preceptor in the Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese tradition. She then must travel to a place where the ordination ceremony will be held, and go through a training program which last from one week to one month before the actual ceremony. In my case, I received the novice ordination in Dharamsala, India, in 1977, and nine years later went to Taiwan to receive the bhikshuni ordination. Going through the one-month training program in Chinese was a challenge, and after two weeks, the other Western nun and I were delighted when the preceptor allowed another nun to translate for us during some of the classes. However, the experience of training as a nun in both the Tibetan and Chinese traditions has enriched my practice and helped me to see the Dharma in all the Buddhist traditions despite the externally diverse, culturally conditioned forms that each uses.

After ordination, we need to receive training in the precepts if we are to keep them well. A new nun should request one of her teachers to give her teachings on the meaning of each precept, what constitutes a transgression and how to purify transgressions should they occur. While a Western nun can usually receive teachings on the precepts without too much difficulty, due to the lack of monasteries for Western nuns, she often misses out on the practical training that comes through living with other nuns in community.

As a nun, our first responsibility is to live according to our precepts as best as we can. Precepts are not a heavy burden, but a joy. In other words, they are voluntarily taken on because we know they will help us in our spiritual pursuit. Precepts liberate us from acting in harmful, dysfunctional, and inconsiderate ways. Novice nuns have ten precepts, which can be subdivided to make 36, probationary nuns have six precepts in addition to these, and fully ordained nuns (bhikshunis) have 348 precepts as listed in the Dharmagupta school of Vinaya, which is the only extant bhikshuni lineage today. The precepts are divided into various categories, each with its corresponding method to deal with transgressions. The root precepts are the most serious and must be kept purely in order to remain as a nun. These entail avoiding killing, stealing, sexual contact, lying about spiritual attainments, and so forth. If these are broken in a complete fashion, one is no longer a nun. Other precepts deal with the nuns’ relationships with each other, with monks, and with the lay community. Still others address how we conduct ourselves in daily activities such as eating, walking, dressing, and residing in a place. Infractions of these are purified in various ways according to their severity: it may entail confession to another bhikshuni, confession in the presence of the assembly of bhikshunis, or relinquishment of a possession obtained in excess or in an inappropriate way, and so forth.

Keeping the precepts in the West in the twentieth century can be a challenge. The precepts were established by the Buddha during his life in India in the 6th century B.C.E., in a culture and time clearly different from our own. While nuns in some Buddhist traditions, for example the Theravada, try to keep the precepts literally, others come from traditions that allow more leeway. By studying the Vinaya and knowing the stories of the specific events that prompted the Buddha to establish each precept, nuns will come to understand the purpose of each precept. Then, they will know how to adhere to its purpose although they may not be able to follow it literally. For example, one of the bhikshuni precepts is not to ride in a vehicle. If we followed that literally, it would be difficult to go to receive or to give teachings, let alone to live as a nun in a city. In ancient India, vehicles were drawn by animals or human beings, and riding in them was reserved for the wealthy. The Buddha’s concern when he made this precept was for nuns to avoid causing suffering to others or generating arrogance. To adapt that to modern societies, nuns should try not to ride in expensive vehicles and avoid becoming proud if someone drives them somewhere in a nice car. In this way, the nuns must learn about the precepts and traditional monastic lifestyle, and then adapt it to the conditions they live in.

Of course, there will be differences of interpretation and implementation among traditions, monasteries in the same tradition, and individuals within a monastery. We need to be tolerant of these differences and to use them to motivate us to reflect deeper on the precepts. For example, Asian nuns generally do not shake hands with men, while most Western nuns in the Tibetan tradition do. If they do this simply to conform to Western customs, I do not see a problem. However, each nun must be mindful so that attraction and attachment do not arise when she shakes hands. Such variations in observing the precepts can be accepted due to cultural differences, etiquette and habit in different countries.

Daily life

The precepts form a framework for further Dharma practice. As nuns, we therefore want to study and practice the Buddha’s teachings and share them with others as much as possible. We also do practical work to sustain ourselves and benefit others. Western nuns live in a variety of circumstances: sometimes in community—a monastery or a Dharma center—and sometimes alone. In all of these situations, our day begins with prayers and meditation before breakfast. After that, we go about our daily activities. In the evening we again meditate and do our spiritual practices. Sometimes it can be a challenge to fit several hours of meditation practice into a busy schedule. But since meditation and prayers are what sustains us, we make strong efforts to navigate the demands made on our time. When the work at a Dharma center is especially intense or many people need our help, it is tempting to take the time out of our practice. However, doing that exacts a toll and if done for too long, can make keeping ordination difficult. Thus, each year we try to take a few weeks—or months if possible—out of our busy lives to do meditation retreat in order to deepen our practice.

As Western nuns we encounter a variety of interesting events in daily life. Some people recognize the robes and know we are Buddhist nuns, others do not. Wearing my robes in the city, I have had people come up to me and compliment me on my “outfit.” Once a flight attendant on a plane leaned over and said, “Not everyone can wear her hair like that, but that cut looks great on you!” A child in a park opened his eyes wide in amazement and said to his mother, “Look, Mommy, that lady doesn’t have any hair!” In a store, a stranger approached a nun and in a conciliatory way said, “Don’t worry, dear. After the chemo is finished, your hair will grow back again.”

When we walk on the street, occasionally someone will say, “Hare Krishna.” I have also had people come up and say, “Have faith in Jesus!” Some people look delighted and ask if I know the Dalai Lama, how they can learn to meditate, or where a Buddhist center is in the town. In the frenzy of American life, they are inspired to see someone who represents spiritual life. After a series of glitches on an airline trip, a fellow passenger approached me and said, “Your calmness and smile me helped me get through all these hassles. Thank you for your meditation practice.”

Even in Buddhist communities, we are treated in a variety of ways because Buddhism is new in the West and people do not know how to relate to monastics. Some people are very respectful to Asian monastics and eager to serve them, but see Western monastics as unpaid labor for the Dharma center and immediately set us to work running errands, cooking, and cleaning for the lay community. Other people appreciate all monastics and are very courteous. Western nuns never know when we go somewhere how others will treat us. At times this can be disquieting, but in the long run, it makes us more flexible and helps us to overcome attachment to reputation. We use such situations to let go of attachment to being treated well and aversion to being treated poorly. Yet, for the sake of the Dharma and the Sangha, we sometimes have to politely instruct people on the proper way to act around monastics. For example, I had to remind members of a Dharma center that invited me to their city to teach that it is not appropriate to put me up at the home of a single man (especially since this one had a huge poster of a Playboy bunny in his bathroom!). In another instance, a young couple was travelling with a group of nuns and we had to remind them that it is not appropriate to embrace and kiss each other on the bus with us. As a young nun, such events annoyed me, but now, due to the benefits of Dharma practice, I am able to react with humor and patience.

The role of the sangha in the West

The word “sangha” is used in a variety of ways. When we speak of the Three Jewels of refuge, the Sangha Jewel refers to any individual—lay or monastic—who has realized emptiness of inherent existence directly. This unmistaken realization of reality renders such a person a reliable object of refuge. The conventional sangha is a group of four or more fully ordained monastics. In traditional Buddhist societies, this is the meaning of the term “sangha,” and an individual monastic is a sangha member. The sangha members and the sangha community are respected not because the individuals are special in and of themselves, but because they hold the precepts given by the Buddha. Their primary objective in life is to tame their minds by applying these precepts and the Buddha’s teachings.

In the West, people often use the word “sangha” loosely to refer to any one who frequents a Buddhist center. This person may or may not have taken even the five lay precepts, to abandon killing, stealing, unwise sexual behavior, lying, and intoxicants. Using “sangha” in this all-encompassing way can lead to misinterpretation and confusion. I believe it is better to stick to the traditional usage.

Individual nuns vary considerably, and any discussion of the role of the sangha has to take this into account. Because Buddhism is new in the West, some people receive ordination without sufficient preparation. Others later find that the monastic life style is not suitable for them, give back their vows, and return to lay life. Some nuns are not mindful or have strong disturbing attitudes and cannot observe the precepts well. It is clear that not everyone who is a Buddhist nun is a Buddha! In discussing the role of the sangha, therefore, we are considering those who are happy as monastics, work hard to apply the Dharma to counteract their disturbing attitudes and negative behavior, and are likely to remain monastics for the duration of their lives.

Some Westerners doubt the usefulness of sangha. Until the political turmoil of the twentieth century, the sangha were by-and-large among the educated members of many Asian societies. Although individual sangha members came from all classes of society, everyone received a religious education once he or she is ordained. One aspect of the sangha’s role was to study and preserve the Buddha’s teachings for future generations. Now in the West, most everyone is literate and can study the Dharma. University professors and scholars in particular study the Buddha’s teachings and give lectures on Buddhism. In previous times, it was the sangha that had the time to do long meditation retreats in order to actualize the meaning of the Dharma. Now in the West, some lay people take months or years off of work in order to do long meditation retreats. Thus, because of the changes in society, now lay people can study the Dharma and do long retreats, just as the monastics do. This makes them wonder, “What is the use of monastics? Why can’t we be considered the modern sangha?”

Having lived part of my life as a lay person and part as a sangha member, my experience tells me that there is a difference between the two. Even though some lay people do the traditional work of the sangha—and some may do it better than some monastics—there is nevertheless a difference between a person who lives with many ethical precepts (a fully-ordained nun or bhikshuni has 348 precepts) and another who does not. The precepts put us right up against our old habits and emotional patterns. A lay retreatant who tires of the austerity of retreat can bring her retreat to a close, get a job, and resume a comfortable lifestyle with beautiful possessions. A university professor may make herself attractive. She may also receive part of her identity by being in relationship to her husband or partner. If she does not already have a partner who gives her emotional support, that option is open to her. She blends in, that is, she can teach Buddhist principles but when she is in society, no one recognizes her as a Buddhist, let alone as a religious person. She does not represent the Dharma in public, and thus it is easier for her behavior to be less than exemplary. If she has many possessions, an expensive car, attractive clothes, and goes on holiday to a beach resort where she lies on the beach to get tan, no one thinks twice about it. If she boasts about her successes and blames others when her plans do not work out, her behavior does not stand out. In other words, her attachment to sense pleasures, praise, and reputation are seen as normal and may easily go unchallenged either by herself or by others.

For a nun, however, the scenario is quite different. She wears robes and shaves her head so she and everyone else around her know that she aspires to live according to certain precepts. This aids her tremendously in dealing with attachments and aversions as they arise in daily life. Men know that she is celibate and relate to her differently. Both she and the men she meets do not become involved in the subtle flirting, games, and self-conscious behavior that people engage in when sexually attracted to another. A nun does not have to think about what to wear or how she looks. The robes and shaved head help her to cut through such attachments. They bring a certain anonymity and equality when she lives together with other monastics, for no one can draw special attention to herself due to her appearance. The robes and the precepts make her much more aware of her actions, or karma, and their results. She has put much time and energy into reflecting on her potential and aspiring to think, feel, speak, and act in ways that benefit herself and others. Thus, even when she is alone, the power of the precepts makes her more mindful not to act in unethical or impulsive ways. If she acts inappropriately with others, her teacher, other nuns, and lay people immediately comment on it. Holding monastic precepts has a pervasive beneficial effect on one’s life that may not be easily comprehensible to those who have not had the experience. There is a significant difference between the lifestyles of Buddhist scholars and lay retreatants on one hand, and monastics on the other. A new nun, who had been a dedicated and knowledgeable lay practitioner for years, told me that before ordination she did not understand how one could feel or act differently simply because of being nun. However, after ordination she was surprised at the power of the ordination: her internal sense of being a practitioner and her awareness of her behavior had changed considerably because of it.

Some people associate monasticism with austerity and self-centered spiritual practice. Contrasting this with the bodhisattva practice of benefiting other beings, they say that monastic life is unnecessary because the bodhisattva path, which can be followed as a lay practitioner, is higher. In fact, there is not a split between being a monastic and being a bodhisattva. In fact, they can easily go together. By regulating our physical and verbal actions, monastic precepts increase our mindfulness of what we say and do. This in turn makes us look at the mental attitudes and emotions that motivate us to speak and act. In doing this, our gross misbehavior is curbed as are the attachment, anger, and confusion that motivate them. With this as a basis, we can cultivate the heart that cherishes others, wishes to work for their benefit, and aspires to become a Buddha in order to be able to do so most effectively. Thus, the monastic life style is a helpful foundation for the bodhisattva path.

The contributions of Western nuns

Many people in the West, particularly those from Protestant cultures, have preconceived ideas of monastics as people who withdraw from society and do not contribute to its betterment. They think monastics are escapists who cannot face the difficulties of ordinary life. My experiences and observations have not validated any of these preconceptions. The fundamental cause of our problems is not the external circumstances, but our internal mental states—the disturbing attitudes of clinging attachment, anger, and confusion. These do not vanish by shaving the head, putting on monastic robes, and going to live in a monastery. If it were so easy to be free of anger, then wouldn’t everyone take ordination right away? Until we eliminate them through spiritual practice, these disturbing attitudes follow us wherever we go. Thus, living as a nun is not a way to avoid or escape problems. Rather, it makes us look at ourselves, for we can no longer engage in distractions as shopping, entertainment, alcohol, and intoxicants. Monastics are committed to eliminating the root causes of suffering in their own minds and in showing others how to do the same.

Although they try to spend the majority of their time in study and practice, monastics offer valuable contributions to society. Like monastics of all spiritual traditions, Western Buddhist nuns demonstrate a life of simplicity and purity to society. By avoiding consumerism—both the clutter of many possessions and the mentality of greed that consumerism fosters—nuns show that it is indeed possible to live simply and be content with what one has. Second, in curtailing their consumerist tendencies, they safeguard the environment for future generations. And third, as celibates, they practice birth control (as well as rebirth control) and thus help stop overpopulation!

By taming their own “monkey minds,” nuns can show other people the methods to do so. As others practice, their lives will be happier and their marriages better. They will be less stressed and angry. Teaching the Buddha’s techniques for subduing disturbing emotions within oneself and for resolving conflicts with others is an invaluable contribution that the nuns can make to society.

Because they are Westerners who have immersed themselves in the Dharma completely, the nuns are cultural bridges between East and West. Often they have lived in multiple cultures and can not only translate from one language to another but also from one set of cultural concepts and norms to another. In bringing Buddhism to the West and engaging in the ongoing process of differentiating the Dharma from its Asian cultural forms, they provide invaluable help along the path to those interested in the Buddha’s teachings. They can also help Westerners to recognize their own cultural preconceptions that block correctly understanding or practicing the Dharma. The nuns are able to speak to diverse audiences and communicate well with all of them, from American high school students to Asian senior citizens.

As Westerners, these nuns are not bound by certain pressures within Asian societies. For example, we can easily receive teachings from a variety of masters of different Buddhist traditions. We are not bound by centuries-old misconceptions about other traditions, nor do we face social pressure to be loyal to the Buddhist tradition of our own country in the same way that many Asian nuns are. This gives us tremendous latitude in our education and enables us to adopt the best from various Buddhist traditions into our lifestyle. This enhances our abilities to teach others and to promote dialogue and harmony among various Buddhist traditions.

The Western nuns offer many skills to the Buddhist community. Some are Dharma teachers; others translate both oral and written teachings. A number of nuns have engaged in long meditation retreats, serving society through their example and their practice. Some nuns are counselors who help Dharma students work through the difficulties that arise in practice. Many people, particularly women, feel more comfortable discussing emotional or personal issues with a nun rather than a monk. Other nuns work in day-care centers, in hospices with the terminally ill, or in refugee communities in their own countries and abroad. Some nuns are artists, others writers, therapists, or professors at universities. Many nuns work in the background: they are the crucial but unseen workers whose selfless labor enables Dharma centers and their resident teachers to serve the public.

The nuns also offer an alternative version of women’s liberation. Nowadays some Buddhist women say that associating women with sexuality, the body, sensuality, and the earth denigrates women. Their remedy is to say that the body, sensuality, and the ability to give birth to children are good. As philosophical support, they speak of tantric Buddhism which trains one to transform sense pleasures into the path. Regardless of whether they are actually able to transform sensuality into the path or not, these women maintain the paradigm that women are associated with sensuality. Nuns offer a different view. As nuns, we do not exalt the body and sensuality, nor do we disparage them. The human body is simply a vehicle with which we practice the Dharma. It doesn’t have to be judged as good or bad. It is just seen as it is and related to accordingly. Human beings are sexual beings, but we are also much more than that. In essence, nuns stop making a big deal out of sex.

Western nuns also have the opportunity to be very creative in their practice and in setting up institutions that reflect an effective way to live a Dharma life in the West. Because they are Western, they are not subject to many of the social pressures and ingrained self-concepts that many Asian nuns must deal with. On the other hand, because they are trained in the Dharma and have often lived in Asian cultures, they are faithful to the purity of the tradition. This prevents them from “throwing the Buddha out with the bath water” when distinguishing the Dharma to bring to the West from the Asian cultural practices that do not necessarily apply to Western practitioners. In this way, nuns are not seeking to change Buddhism, but to be changed by it! The essence of the Dharma cannot be changed and should not be tampered with. Buddhist institutions, however, are created by human beings and reflect the cultures in which they are found. As Western nuns, we can change the form that these Buddhism institutions take in our society.

Prejudice and pride

People often ask if we face discrimination because we are women. Of course! Most societies in our world are male-oriented, and Buddhist ones are no exception. For example, to avoid sexual attraction that is a distraction to our Dharma practice, monks and nuns are housed and seated separately. Since males have traditionally been the leaders in most societies and because monks are more numerous than nuns, the monks generally receive the preferable seats and living quarters. In Tibetan society, the monks receive a better education and more respect from society. There is also a scarcity of ordained female role models. The public—including many Western women—generally give larger donations to monks than to nuns. Traditionally the sangha has received their material requisites—food, shelter, clothing, and medicine—through donations from the public. When these are lacking, the nuns find it more difficult to receive proper training and education because they cannot cover the expenses those entail and because they must spend their time, not in study and practice, but in finding alternative means of income.

As Western nuns, we face similar external circumstances. Nevertheless, Western nuns are generally self-confident and assertive. Thus, we are apt to take advantage of situations that present themselves. Due to the relatively small number of Western monks and nuns, we are trained and receive teachings together. Thus the Western nuns receive the same education as Western monks, and our teachers give us equal responsibilities. Nevertheless, when participating in Asian Dharma events, we are not treated the same as men. Interestingly, Asians often do not notice this. It is so much “the way things are done” that it is never questioned. Sometimes people ask me to discuss at length how nuns in general, and Western nuns in particular, face discrimination. However, I do not find this particularly useful. For me, it is sufficient to be aware in various situations, understand the cultural roots and habits for the discrimination, and thus not let it affect my self-confidence. Then I try to deal with the situation in a beneficial way. Sometimes this is by politely questioning a situation. Other times it is by first winning someone’s confidence and respect over time, and later pointing out difficulties. However, in all situations, it necessitates maintaining a kind attitude in my own mind.

Many years ago, I would become angry when encountering gender prejudice, particularly in Asian Buddhist institutions. For example, I was once attending a large “tsog” offering ceremony in Dharamsala, India. I watched three Tibetan monks stand up and present a large food offering to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Other monks then rose to distribute offerings to the entire congregation. Inside I fumed, “The monks always do these important functions and we nuns have to sit here! It’s not fair.” Then I considered that if we nuns had to get up to make the offering to His Holiness and distribute offerings to the crowd, I would complain that we had to do all the work while the monks remained seated. Noticing this, I saw that both the problem and the solution to it lay in my attitude, not in the external situation.

Being a Dharma practitioner, I could not escape the fact that anger is a defilement that misconstrues a situation and is therefore a cause of suffering. I had to face my anger and my arrogance, and apply the Dharma antidotes to deal with them. Now it is actually intriguing and fun to deal with feeling offended. I observe the sense of “I” that feels offended, the I who wants to retaliate. I pause and examine, “Who is this I?” Or I stop and reflect, “How is my mind viewing this situation and creating my experience by the way I interpret it?” Some people think that if a woman relinquishes her anger and pride in such circumstances, she must see herself as inferior and will not work to remedy the situation. This is not a correct understanding of the Dharma, however; for only when our own mind is peaceful can we clearly see methods to improve bad circumstances.

Some people claim that the fact that fully ordained nuns have more precepts than monks indicates gender discrimination. They disapprove of the fact that some precepts which are minor transgressions for monks are major ones for nuns. Understanding the evolution of the precepts puts this is proper perspective. When the sangha was initially formed, there were no precepts. After several years, some monks acted in ways that provoked criticism either from other monastics or from the general public. In response to each situation, the Buddha established a precept to guide the behavior of the sangha in the future. While bhikshus (fully ordained monks) follow precepts that were established due to unwise behavior of the monks only, bhikshunis (fully ordained nuns) follow the precepts that arose due to inappropriate behavior of both monks and nuns. Also, some of the additional precepts relate only to female practitioners. For example, it would be useless for a monk to have a precept to avoid promising a nun a menses garment but not giving it!

Personally speaking, as a nun, having more precepts than a monk does not bother me. The more numerous and the stricter the precepts, the more my mindfulness improves. This increased mindfulness aids my practice. It is not a hindrance, nor is it indicative of discrimination. The increased mindfulness helps me progress on the path and I welcome it.

In short, while Western nuns face certain difficulties, these very same situations can become the fuel propelling them towards internal transformation. Women who have the inclination and ability to receive and keep the monastic precepts experience a special fortune and joy through their spiritual practice. Through their practice in overcoming attachment, developing a kind heart, and realizing the ultimate nature of phenomena, they can benefit many people directly and indirectly. Whether or not oneself is a monastic, the benefit of having nuns in our society is evident.

Bibliography

-

- Batchelor, Martine. Walking on Lotus Flowers. Thorsons/HarperCollins, San Francisco, 1996.

- Chodron, Thubten, ed. Blossoms of the Dharma: Living as a Buddhist Nun. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, 2000.

- Chodron, Thubten, ed. Preparing for Ordination: Reflections for Westerners Considering Monastic Ordination in the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition. Life as a Western Buddhist Nun, Seattle, 1997. For free distribution. Write to: Dharma Friendship Foundation, P. O. Box 30011, Seattle WA 98103, USA.

- Gyatso, Tenzin. Advice from Buddha Shakyamuni Concerning a Monk’s Discipline. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, 1982)

- Hanh, Thich Nhat. For a Future to Be Possible. Parallax Press, Berkeley, 1993.

- Horner, I. B. Book of the Discipline (Vinaya-Pitaka), Part I-IV in the Sacred Books of the Buddhists. Pali Text Society, London, 1983 (and Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd, London, 1982.)

- The Profound Path of Peace, Issue No. 12, Feb. 1993. International Kagyu Sangha Association (c/o Gampo Abbey, Pleasant Bay, N.S. BOE 2PO, Canada)

- Mohoupt, Fran, ed. Sangha. International Mahayana Institute. (Box 817, Kathmandu, Nepal)

- Murcott, Susan, tr. The First Buddhist Women: Translations and Commentary on the Therigatha. Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1991.

- Sakyadhita newletter. Past issues available from: Ven. Lekshe Tsomo, 400 Honbron Lane #2615, Honolulu HI96815, USA.

- Tegchok, Geshe. Monastic Rites. Wisdom Publications, London, 1985.

- Tsedroen, Jampa. A Brief Survey of the Vinaya. Dharma Edition, Hamburg, 1992.

- Tsomo, Karma Lekshe, ed. Sakyadhita Daughters of the Buddha. Snow Lion, Ithaca NY, 1988.

- Tsomo, Karma Lekshe. Sisters in Solitude: Two Traditions of Monastic Ethics for Women. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1996.

Yasodhara (formerly NIBWA) newsletter. Past issues available from: Dr. Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

- Wu Yin, Teachings on the Dharmagupta Bhikshuni Pratimoksa, given at Life as a Western Buddhist Nun. For audio tapes, please write to Hsiang Kuang Temple, 49-1 Nei-pu, Chu-chi, Chia-I County 60406, Taiwan.

This article is taken from the book Women’s Buddhism, Buddhism’s Women, edited by Elison Findly, published by Wisdom Publications, 2000.

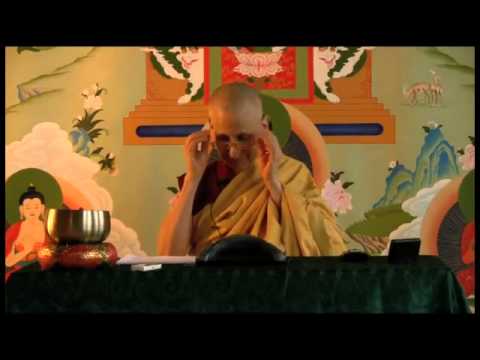

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.