Meditating on death and impermanence

Stages of the Path #23: Death & Impermanence

Part of a series of Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on the Stages of the Path (or lamrim) as described in the Guru Puja text by Panchen Lama I Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen.

- Where the meditation on death and impermanence fits in the sequence

- How vital the meditation on death is

- Challenging the status quo

We’re moving on to the third verse:

Aghast at the searing blaze of suffering in the lower realms,

we take heartfelt refuge in the Three Jewels.

Inspire us to eagerly endeavor to practice the means

for abandoning negativities and accumulating virtues.

This verse starts out with, “Aghast at the searing blaze of suffering of the lower realms,” (in the lamrim the meditation on unfortunate rebirths) which is followed by, “We take heartfelt refuge in the Three Jewels.” That’s the next meditation in the lamrim. And then, “Inspire us to eagerly practice the means for abandoning negativities and accumulating virtues” is the meditation on karma, which is the following one.

Then you’re going to say, “What happened to death and impermanence?” Did it die? [laughter] It’s actually referred to in the second verse and in the third verse. In the second verse, when we talked about our precious human life and partaking of its essence, making it worthwhile and not be distracted by the meaningless affairs of this life, one of the antidotes to the eight worldly concerns that distract us is the meditation on death and impermanence. Then similarly, the meditation on death and impermanence is what we must do so that we even get a feeling of the possibility of having an unfortunate rebirth. Because if we don’t think of our death we’re not going to think about what comes after that.

The meditation on death and impermanence is really quite a vital one. They say if you don’t remember death and impermanence in the morning you’ll waste your morning, if you don’t remember it in the afternoon you’ll waste your afternoon, and if you don’t remember it at night you’ll waste your night. The idea is that the fact that we’re going to die, and we aren’t going to continue to exist forever, is what acts as the mirror that makes us ask ourselves, “What am I doing in my life? And what is of value in my life? And at the time I die, when I look back on my life, what will I have rejoiced about having done, and what will I regret having done?” The fact of our mortality puts us up against those very important questions. And those questions, I think, are the most important ones we ever have to ask in our lives, about “what’s the meaning of my life?” What is of value in our lives?

So often in our society people don’t like to ask those questions. They’re afraid to because it challenges the status quo. It challenges all the “shoulds” and “oughts” and “supposed to bes” that you grow up with, of how you’re supposed to be, and what you’re supposed to do, and have, and act, and so forth. And saying “well, I’m going to die, so what meaning do all these things that I should and supposed to do have if I’m going to die and separate from all of them. So that whole questioning can be a terrifying process for people because the more attached you are to something the harder it is to say, “I made a mistake in what I did, I made my priorities incorrectly.” Because if you’re very attached, and then it’s so hard on your ego to say “I made my priorities incorrectly and now I have to re-prioritize and do things differently. For some people that process is very scary because they get into a lot of self-judgment. They don’t need to get into self-judgment, they could say, “I acted on automatic at that time in my life because nobody ever told me, “Think about death and impermanence.” Now I have this in front of me, it’s really important to think about, and now it’s really invigorating my life, giving me a lot of oomph and courage and enthusiasm to live my life in a different way. So people could look at that self-examination process in that way. They don’t have to look at it as “Oh, death and impermanence is telling me that everything I did in my life until now is useless, and therefore I’m bad.” You see where we go wrong? We always add the “And I’m bad” to it. Which, why do we have to add “and I’m bad”? It has nothing to do with that.

When we evaluate our lives in that mirror of “it’s not going to last forever so what’s really meaningful?” Then that helps us get very clear on what’s important and what’s useless. And it can actually make our mind quite clear, quite strong in following what we know to be really true and meaningful. Of course, sometimes in our lives we don’t know what’s true and meaningful. That fits in with how fortunate we are to have a precious human life in which we have met the teachings that provide an alternative for us to scrutinize, to see if that’s a meaningful alternative. How precious our life is that we’ve met the teachings, we see some alternatives. And then to have the inspiration to really follow that and do that, rather than just live on automatic, do what we think we’re supposed to do, and then get to the point where we’re dying and say, “What did I spend my whole life doing?” Because at the time of death it’s our karma that comes with us, whereas all the things that we spent our lives doing to please other people and be what we’re supposed to be, all those things get left behind.

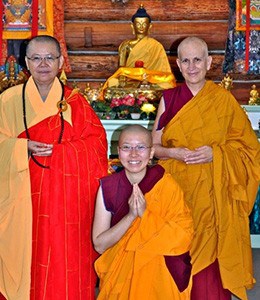

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.