How can we deal with anger?

Buddhism teaches us not to become angry. But isn’t anger a natural part of being human and therefore acceptable if it were to arise occasionally?

From the point of view of a being in samsara, who is caught in the cycle of existence and influenced by afflictions and karma, anger is natural. But the real question should be whether anger is beneficial. Just because it is natural does not mean it is beneficial. When we examine anger more closely, we see firstly that anger is based on exaggerating the negative quality of someone or projecting negative qualities that are not there on a person or object. Secondly, anger is not beneficial because it creates many problems for us in this life and creates negative karma which will bring about suffering for us in our future lives. Anger also obscures the mind and prevents us from generating Dharma realizations and thus from attaining liberation and enlightenment.

Why is it that certain people get angry easily while others do not? Is this due to their past karma and thus nothing can be done about it?

One of the results of karma is that people have the tendency to do the same action again. This result of karma could be at play when people have a strong tendency towards malicious thought or they act out their anger by harming others physically or verbally.

However, the fact of anger arising in the mind to begin with is due to the seed of anger existing in the mindstream. If that seed is strong because someone had a habit of getting angry in previous lives, then he could easily become angry in this life due to the habit. Other people are less easily angered because of practicing patience and loving-kindness in their previous lives. They established a habit that is the opposite of anger and thus those positive emotions arise more frequently in this live.

However, when we say that there are elements of karma and habit involved, this does not mean that there is nothing that can be done about it. We may carry the habit of anger but because of the function of cause and effect, we can reduce our anger (effect) if we practice the antidotes to anger (cause).

The Buddha taught methods for counteracting anger and for purifying negative karma created by anger. So there is absolutely no excuse to say that you are born like that and there is nothing that can be done about it. Don’t think, “I’m just an angry person. There’s nothing that can be done, so everyone just has to live with me and love me anyway.” That’s nonsense!

Sometimes, we act angry with our children so that they behave. This is done out of compassion. Is this acceptable in Buddhism?

It is true that sometimes when children misbehave, it may help to speak strongly to them. But that does not necessarily mean speaking with anger. Because people don’t communicate well when they are angry, if your mind is filled with anger when you speak to your children, they might not even understand what they have done wrong and what you expect of them. Instead, practice remaining calm inside, knowing that they are just children and are imperfect sentient beings. They need your help to become good people. With the motivation to help them, correct their mistaken actions. You may have to speak strongly to them in order to communicate your wishes. For example, when young children are playing in the middle of the street, if you don’t speak strongly they probably won’t understand that they should not do this because, by themselves, they don’t see the danger. But if you are firm, they will know “I better don’t do this.” You can be stern with children without being angry.

Some psychologists say that it is better to release negative emotions such as anger rather than keeping them within us as it will affect our health. What does Buddhism have to say about this?

I think psychologists assume that there are only two things that can be done about anger. One is to express it and the other is to suppress it. From a Buddhist perspective, both are unhealthy. If you suppress anger, it is still there and that is not good for your health. If you express it, it is not good as well because you might harm others and you will create negative karma in the process.

So Buddhism teaches us how to look at the situation from a different perspective and how to interpret events in a different way. If we do that, we will find that there is no reason to get angry to start with. Then there is no anger to express or to suppress.

For example, when someone tells us that we did something wrong, we usually think that person is trying to harm us. But look at it from a different perspective and consider that he may be giving us some useful information. He may be trying to help us. By seeing the situation in this way, we won’t get angry. In other words, what creates anger is not so much what the other person did, but how we chose to interpret what he did. If we interpret it in a different way, the anger will not arise.

Another example is let’s say someone lied to or deceived us. Think, “This is the fruit of my negative karma. In a previous lifetime, under the influence of my self-centered attitude I deceived and betrayed others. Now I am receiving the result of this.” In this way, instead of blaming others, we see that the cause of our being deceived or betrayed is our own self-centeredness. There’s no reason to get mad at others. We realize that our self-centeredness is the real enemy. Then, we will have a strong determination not to act like that again because we know that self-centeredness brings suffering. If we want to be happy, we must release the self-centeredness, so we do not act so negatively toward each other.

What are the antidotes to prevent anger from arising? As lay people, how do we apply them in our everyday life?

Whether you are lay or monastic, applying antidotes to destructive emotions is important. We must practice the antidotes that the Buddha taught again and again. Listening to one Dharma talk or meditating once cannot change mistaken ways of interpreting events and destructive emotions. There isn’t the opportunity now to describe the various antidotes in depth, so I’ll refer you to some books that will help you: Healing Anger by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Guide to a Bodhisattva’s Way of Life (chapter 6) by Shantideva, and my book, Working with Anger.

In training my mind in patience, I find it beneficial to recall a situation in the past when I got angry, had ill will, or held a grudge towards another person. Then, I select one of antidotes to anger and practice seeing that situation with the Dharma antidote. In that way, I start to heal my negative emotions from that past event and, in addition, gain experience in practicing the antidote and seeing that situation from a different angle. I’ve done this often because I held onto a lot of anger. Now when I find myself in similar situations, I don’t get as angry as before because I’m more familiar with the antidotes and it’s easier to apply them in the actual situation. At some point in my training, due to being very familiar with the antidotes, I will not even get angry to start with.

There are a few slogans which I remember when anger begins to arise. One is, “Sentient beings do what sentient beings do.” That is, sentient beings are under the influence of ignorance, afflictions, and karma and. Any being that is under the influence of those obscurations is going to do harmful actions. It is clear that living beings are imperfect. So my expectation that they be perfect is totally unrealistic. When I accept this, I understand why they act like that and am more compassionate regarding what they do. They are caught in this dreadful prison of cyclic existence. I don’t what them to suffer, and I certainly don’t want to inflict more suffering on them by getting angry. Holding this big picture of sentient beings trapped in cyclic existence enables us to feel compassion instead of anger when they act in mistaken ways.

How can we learn to accept criticism without being angry?

If someone criticizes you, don’t pay attention to the tone, vocabulary, or volume of their voice. Just focus on the content of their criticism. If it is true, there’s no reason to get angry. For example, if someone says, “There is a nose on your face,” you are not angry because it is true. There is no use pretending we don’t have a nose—or didn’t make a mistake—because everyone, including us, knows we did. As Buddhists we must always improve ourselves and so we should put our hands together and say, “Thank you.” On the other hand, if someone says, “There is a horn on your face” there is no reason to get angry because that person is mistaken. We can explain this to the person later when they are receptive to listening.

Can we meditate on our anger when it arises? How do we do it?

When we are in the midst of feeling a strong negative emotion, we are very involved in the story that we are telling ourselves about what is happening, “He did this. Then he said that. What nerve he has! Who does he think he is speaking to me that way? How dare he!” At that time, we cannot take in any new information. When my mind is like that, I try to excuse myself from the situation, so that I will not say or do something harmful that I will regret later. I watch my breath and calm down. At this time, it can be helpful to sit down and focus on what anger feels like in our body and in our mind. Just focus on the feeling of anger and pull our mind out of thinking about the story. When we are calmer and are able to practice the antidotes, we can come back to reassess that situation from a different perspective.

Patience is the opposite of anger and is highly praised in Buddhism. But sometimes others take advantage when we cultivate patience. What do we do in such a situation?

Some people fear that if they are kind or patient, others will take advantage of them. I think they misunderstand what patience and compassion mean. Being patient and compassionate does not mean you let people take advantage of you. It does not mean that you allow other people to harm and beat you up. That is stupidity, not compassion! Being patient means being calm when confronted with suffering or harm. It does not mean being like a doormat. You can be kind and at the same time, be firm and have a clear sense of your own human dignity and self-worth. You know what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior in that situation. If you are clear in this way, others will know that they cannot take advantage of you. But if you are fearful, they will sense your fear and take advantage of that. If you try very hard to please people and do what they want so that they will like you, other people will take advantage because your own mind is unclear and attached to approval. But when your mind is clear and patient, there is a different energy about you. Others won’t try to take advantage of you and even if they did, you would stop them and say, “No, that’s not appropriate.”

Is there a difference in being angry and being hateful?

Anger is when we have a rush of hostility towards somebody. Hate is when we hold on to that feeling of anger over period of time, generate a lot of ill will, and contemplate how to retaliate, take revenge, or humiliate the other person. Hatefulness is anger that has been held on to for a long time.

Hate is very harmful to ourselves and others. In addition to creating so much negative karma and motivating us to harm others, hate ties us up in misery. No one is happy when his or her mind is full of hate and vengefulness. Furthermore, when parents are hateful, they are teaching their children to hate because children learn emotions and behavior by observing their parents. Therefore, if you love your children, do your best to abandon hate by forgiving others.

In Buddhism, anger is one of the three roots of evil, the other two being greed and ignorance. Which should be our first priority to eradicate as part of our spiritual practice?

That depends very much on the individual. The great masters say that we should look inside of ourselves and see which one is stronger, which disturbs our mind most, and then focus on that and try to diminish it. For example, if you see that your confusion and lack of good judgment is the most troublesome of the three, then emphasize the development of wisdom. If attachment, lust, or desire are the greatest, then first work to diminish those. If anger is the most harmful in your life, do more meditation on patience, love, and compassion. When we emphasize reducing one affliction, we should not neglect to apply the antidotes to the other two when needed.

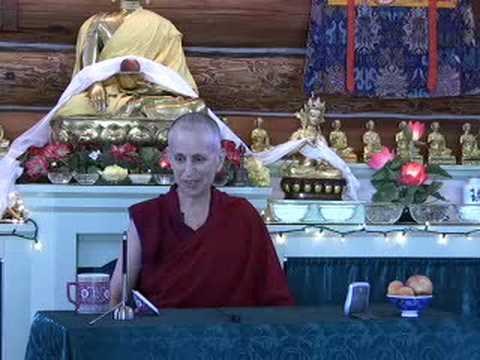

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.