Inside-out practice

By J. H.

J. H., age 26, resides in a maximum security prison in the Midwest, serving a life sentence without parole. We asked him what it’s like to practice Buddhism in a maximum security prison.

If you were asked, “What’s it like to practice Buddhism in a maximum security prison,” you’d probably think, “What an odd question.” I feel the same way. The difference between us is that I am practicing Buddhism in a maximum security prison, and have been for five of the last ten years. That’s how long I’ve been here, ten years. So why does it seem like an odd question to me when it applies perfectly to my life? Let me explain.

When I wake up in the morning, to the sound of a blaring horn that resembles a souped up alarm clock, I don’t really want to get up yet. Six o’clock comes entirely too early in the morning. I have to get up, though. It’s almost time for breakfast and work is right around the corner. I suppose it’s the same for you; morning just coming too early.

Having arisen and washed my face, I lie back down and wait for breakfast. On my good days I go over my bodhisattva vows; on my bad days I grumble about how uncomfortable my bed is. Of course, I also grumble about my cell mate, with his annoying habits (it doesn’t matter what the real or imagined habit is, at six o’clock in the morning, all habits are annoying). I suppose it’s like this for you, lying next to your husband or wife, waiting for your day to begin, mumbling to yourself about your partner’s obnoxious snoring.

When I get to breakfast, I find that my mood comes with me. If I’m grumpy, then the food is terrible. If my mood was good, then the food is delicious. Of course, waiting in line for breakfast, regardless of my mood, always makes me impatient. So I get a few minutes, while waiting in line, to consider this Dharma lesson. Like most Dharma lessons, this one isn’t any fun to learn. Nonetheless, I stand there and contemplate the karma that comes from impatience, and the way I promised to help all sentient beings (but I don’t recall including anything about letting all those sentient beings in front of me in line).

Having acquired my tray, I sit at a table with either friends or strangers. The designations aren’t fixed; some days friends are strangers, and vice-versa—the way I imagine it for most couples. I bow my head and pray, making offerings of the first bite of my food to the Three Jewels. Sometimes the other people at the table are quiet and respectful of my prayer; sometimes they look at me with disdain. I suppose it’s like that for you too. Sometimes people respect you for what you are trying to do, and sometimes they don’t.

Breakfast ends and the wait for work begins. Work is supposed to begin at 7:30 a.m., but there are a hundred things which can change that. Inevitably, I get another Dharma lesson in patience at this time of the day. I sit there waiting, impatiently, for everyone who must be in place to get to his or her place so I can go to work. I guess this is equivalent to rush hour.

Work, I love work. I am blessed with a good job, one that helps people and that challenges me. Of course, some days the challenges are so great that I end up stressed out. Some days everything goes smoothly, and I feel very happy and self-satisfied. Whichever way that it goes, I always end up liking my job too much. Not that this is apparent to me at the time I am working. I only become aware of this when I sit down on my cushion to meditate, late in the evening, and realize that all I can do is to think about work and ways to problem solve the challenges of the day. I guess you know what I am talking about.

Then is a lunch break, which inevitably leads to another lesson in patience. Again, I can’t get back to work until all the people who have to be in their places for me to move are in their places. You know what I’m talking about, right? It’s the lunchtime rush.

Work ends and yoga begins (on some days). Man, is it hard to go from work to yoga. It’s necessary, though, if I am to stay healthy. Working through the asanas, feeling grumpy at my yoga partner because he’s going too fast or breathing too loud, or doing whatever it is he’s doing … maybe it’s my really not wanting to be doing yoga at that moment, though I am not going to admit it.

By the time yoga is done, I will be glad I did it. Then, I will thank my yoga partner with “namaste.” Of course, that means I will get another Dharma lesson, the one about the emptiness of labeling someone too this or too that.

Finally supper arrives, and then the evening. The evening is when I find time to read and study. Some days it’s wonderful lamrim studies. Some days it’s computer manuals and programming books. Always it is either Dharma or work, that’s the division in my life.

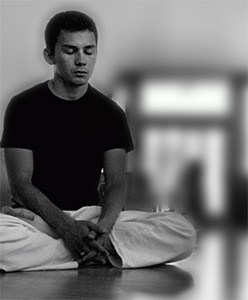

Three or four hours pass, studies have gone well. I am usually pretty exhausted by now; but I know bedtime’s not far off. Lockdown time comes and things finally settle down. The last sitting or standing count happens and we are free to do as we please. So, I set up my little altar and my wool blanket. My cellmate is kind and gets up on his bunk for the next hour. I pray, I prostrate, I settle in with my mala, and I undertake my meditation practice. It’s 10:30 at night; kind of late to be starting a Dharma practice, but that’s the only time it’s quiet around here, and the noise of the world seems to dictate when I meditate.

At different times there are meditation classes, Yoga classes, trauma and wellness classes. No matter what, though, the days are always filled with Dharma lessons.

So you might be wondering why I said at the beginning that being asked what it’s like to practice in a maximum security prison was such an odd question. It’s odd because practicing Buddhism inside a prison is just like practicing on the outside.

You might say, “Oh, but you are surrounded by murderers and rapists, won’t they think you are weak if you talk about compassion and practice loving-kindness? Won’t that put you in harm’s way?” I ask you, “Where do you think all these people lived before they came to prison? That’s right, in your neighborhood.”

“But what about the guards, don’t they pick on you and ridicule you? How can you develop bodhicitta in that kind of environment?” Oddly enough, guards are people too. And like other people in the world, they generally treat you the way you treat them. Certainly there are a few difficult ones, but that’s only because they are suffering (like all of us). Besides, you don’t learn patience from your friends; you learn it from those blessed bodhisattvas in disguise that irritate you to no end.

Ultimately, I am simply saying this. We are all practicing in a maximum security prison. It’s called samsara.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.