The wisdom of kindness

Despite spending most of her life pursuing enlightenment, Ani Tenzin Palmo, one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun, gives remarkably straightforward advice. Originally published in The Buddhist Channel.

Bangkok, Thailand—This scene could be a projection of the mind—a cut from an on-going movie that has been recycled again and again. But to have Ani Tenzin Palmo playing a role in it, with an immaculately clean kitchen filled with nuns and lay women at Suan Mokkh forest monastery as the setting, makes this a scenario no film director could have conceived or even dreamed of.

And yet here she is, sitting snugly on a plastic chair, chatting, gesturing and laughing her hearty, joyous laugh.

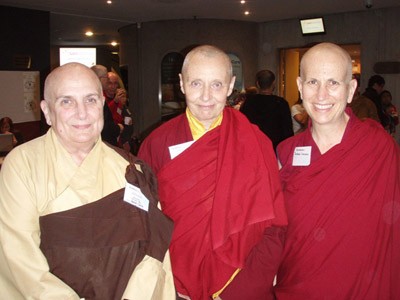

Although there are differences in language and robe colour of the “cast”, the 63-year-old Tibetan Buddhist nun seems to be mingling well with her new Thai friends. This is not surprising given these friends share Tenzin Palmo’s gender and, more importantly, her aspiration to attain enlightenment—if not in this lifetime then in one of the numerous sequels they believe are likely to follow.

That’s exactly the message that the venerable bhikkuni (female monk) repeated throughout her recent whirlwind tour of Thailand. “Don’t waste your time,” she urged the different groups she spoke to, be they Thais or foreigners meditating at Suan Mokkh, business people in Bangkok, Mae Chi students at Mahapajapati Buddhist College for nuns in Nakhon Ratchasima or the general public at retreats held in Nakhon Nayok and Chiang Mai. To all she stressed the importance of nurturing a constant state of mindfulness.

“Don’t waste your human birth, for if you do, the opportunity may not come again for many, many lifetimes.

When I discovered the Buddha-dharma through a course [which was] actually on Thai Buddhism, when I was 18, I recognised immediately that this is the only thing in the world that is important. Therefore, I decided I should try to lead a life that would not distract me from the main point of Buddha-dharma: To attain enlightenment as much as one can in one’s lifetime in order to benefit others, because what else could matter?”

Tenzin Palmo has lived her life in pursuit of what she now teaches. In 1964, aged 20, she left her home in London to undertake a spiritual journey in India. A year later, shortly after meeting her Tibetan guru, the late eighth Khamtrul Rinpoche, Tenzin Palmo was ordained as a novice. (She received full bhikkuni ordination in 1973.) In the following years she diligently studied both Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and the myriad rituals and meditation techniques of Vajrayana Buddhism. At one time, she was the only nun practicing at a temple of 100 monks.

Her journey has been far from easy. Cave in the Snow, Tenzin Palmo’s biography, written by journalist Vicki Mackenzie, details the patriarchal atmosphere within the Tibetan monastic community (a situation found in many Buddhist countries). In 1970, she received permission from her guru to move to another temple in the Himalayan valley of Lahaul.

After spending six years at that snow-bound land, Tenzin Palmo took a radical step on her quest for enlightenment: She began a solitary retreat in a cave 4,000 metres above sea level. For 12 years, the final three in strict isolation, she led a rugged, precarious existence surviving on basic foods in the sparsest conditions while enduring the extreme weather of the Himalayas.

Now, in the dimmed light of the kitchen at Suan Mokkh, such a legendary feat seems a lifetime away. But is it really? The topics of Tenzin Palmo’s chats with the nuns and upasikas (lay practitioners) here range from Hollywood movies like Groundhog Day (she thinks it’s a very Buddhist film) and The Matrix (much too violent), to how to achieve a balance between spiritual retreats and community work and whether living in a cave really helps get rid of one’s ego.

Tenzin Palmo’s serene, light-hearted persona belies her incredible internal strength. Despite her frail health and the packed schedule of her recent visit—almost every day she had to travel, give dharma lectures and answer difficult questions on spirituality—Tenzin Palmo maintains her lucid sharpness. And her immense kindness also. Every now and then, when she senses anguish or a need for solace, she approaches one of the women she’s chatting with and gives them a bear hug. This motherly embrace is the manifestation of kalayanamitta (true friendship).

“That’s why you need a female monk,” she says after hugging a woman in tears. “Because [male] monks can’t do that.”

This casual giving of love is mixed with an indescribable sense of non-attachment, an awareness of space that enables Tenzin Palmo to accommodate others but never cling to them. During her lecture at Suan Mokkh (where she was offered the prestigious speaker’s seat once occupied by the monastery’s late founder, Buddhadasa Bhikkhu), Tenzin Palmo told a story about her mother’s love as an example of a love that does not bind.

“When I was 19 years old, I wanted to go to India to find a spiritual teacher. Finally, I got an invitation letter. I remember running along the road to meet my mother as she was coming from work and saying to her ‘I’m going to India!’ And she replied ‘Oh yes dear, when are you leaving?’ Because she loved me, she was happy for me to leave her.”

She went on to explain the moral of the story. “We mistake love and attachment. We think they are the same thing, but actually, they are opposites. Love is ‘I want you to be happy.’ Attachment is ‘I want you to make me happy.”

Tenzin Palmo’s dharma talks are simple yet moving because every word she says is tinged with sincerity. As she speaks, her words seem to spring from within through a process as natural as breathing. In a way she is like a tree, sucking in pollution and harm and releasing it as positive energy.

How does she maintain this crisp state of awareness? To be “in” but not “of” the world? One analogy Tenzin Palmo often uses is to compare one’s existence to a movie. Most people let themselves become completely immersed in the drama that is their life. But if you take a step back, you can see a completely different picture.

“What you’ve got, really, is just a projector of light and in front of that light are little transparent frames that are moving very, very fast. And that projects what looks like reality. When we see that it’s just a movie, we can still enjoy it, but we don’t have to take it so seriously.”

The cultivation of mindfulness, she says, can enable us to see “through” the rapid movement of those “frames of thought”. Once we master this practice, the “mind moments” will become remarkably slower, slow enough for us to catch the gaps between each frame.

And what lies beneath the illusory “truth” of the mind? Tenzin Palmo describes the presence of the true, original mind (“Buddha nature”) as the sky stripped of clouds or a mirror without dirt. Something clear, luminous, and infinite. “It’s always there, it belongs to everybody. There is no ‘I’, no centre.”

But for most of us most of the time, we are trapped in our relative mind. A mind that “naturally makes a division between the thinker and everyone outside the thinker. That thinks in terms of past, present and future.

“The point is to get some glimpses of the clear blue sky behind the clouds or the mirror beneath the dirt. So even though there’s thick layers of clouds or dirt, you know that it’s not the real thing and that there’s something beyond that.

“When we are completely in this state of naked primordial awareness all the time, 24 hours a day, whether we are awake or asleep, we become Buddha. Until then, we are still on the path.”

But do we all have to cocoon ourselves in a cave in order to seek enlightenment? From her experience, Tenzin Palmo describes intense solitary retreat as a “a pressure cooker. It gives you the chance to really look inwards.” But, if the practitioner becomes addicted to the quiet atmosphere or thinks they have become superior to others, then “the practice has gone wrong”, she says.

For Tenzin Palmo, true dharma is found in daily life. It is the ability to “be here and now and put others before oneself. This helps us to overcome our innate selfishness and our innate concern with only me, me, me.”

One story she often shares tells of an invaluable piece of advice she received from a Catholic priest. Asked if he thought Tenzin Palmo should resume her retreat or undertake the far more formidable task of starting a nunnery, the priest straight away recommended the second option.

“He said we are like rough pieces of wood. If we rub ourselves with silk or velvet, it may be nice, but it won’t make us smooth. To become smooth, we need sandpaper.”

Minutes pass into hours. At some point, Tenzin Palmo closed her eyes while still sitting in the same plastic chair. It has been an exhaustingly long day for her. But is the venerable monk sleeping? Or is she meditating like she did for most of her time in the mountains 20 years ago? The two frames of possibility almost merge, almost transcend the boundaries of space and time. Which is real? And which is just a projection from the perpetually rolling film of the mind?