A Benedictine’s view

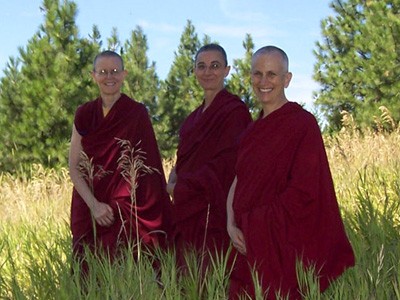

Spiritual Sisters: A Benedictine and a Buddhist nun in dialogue - part 1 of 3

A talk given by Sister Donald Corcoran and Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron in September 1991, at the chapel of Anabel Taylor Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. It was cosponsored by the Center for Religion, Ethics, and Social Policy at Cornell University and the St. Francis Spiritual Renewal Center.

- The monastic archetype

- The Benedictine tradition

- My vocation and experience as a nun

- Spiritual formation

A Benedictine’s view (download)

Part 2: A bhikshuni’s view

Part 3: Comparing and contrasting views

We have great fortune to be here together, to learn from each other and to share with each other. This evening I would like to speak about four topics: the monastic archetype, my particular tradition, how I came to be a Benedictine nun, and spiritual formation.

The monastic archetype

Monasticism is a worldwide phenomenon: we find Buddhist monks and nuns, Hindu ascetics, the Taoist hermits of China, the Sufi brotherhoods, and Christian monastic life. Thus, it’s accurate to say that monastic life existed prior to the Gospel. For whatever reasons, there is an instinct in the human heart which some persons have chosen to live out in a deliberate and continual way for their entire life; they have chosen a life of total consecration to spiritual practice. In a New York Times book review of Thomas Merton’s poems a number of years ago, the reviewer commented that a remarkable thing about Merton was that he made an extreme life option seem reasonable. That was a wonderful comment about monastic life! It is an extreme life option: the normal way is the life of the householder. The way of the monastic is the exception, and yet I think that there is a monastic dimension to every human heart—that sense of the absolute, that sense of a preoccupation with the ultimate and what it means. This has been lived out and concretized historically in several of the major religious traditions of humankind. So, Venerable Thubten Chodron and I are here this evening to speak to you and share with you about our own experience in our traditions as women monastics and what monastic life means.

The Benedictine tradition

I am a Roman Catholic Benedictine and love my tradition very much. In fact, I think any good Buddhist would tell me that I am far too attached, but maybe a little ebullience like that creates some success. Many years ago a sister from another order told me, “Maybe we should just finish with having so many Orders in the Church and have just one group called the American Sisters.” I said, “That’s fine. As long as everyone wants to be Benedictine, that’s fine!”

Founded in 529, the Benedictine order is the oldest monastic order of the West. St. Benedict is the patron of Europe and is called the father of Western monasticism. Two and one-half centuries of monastic life and experience happened before him and he is, to some extent, the conduit through which the earlier traditions—the spirituality of the desert fathers, John Cassian, Evagrius, and so on—was channeled through southern France, Gaul. The source that Benedict primarily used, “The Rule of the Master,” is a distillation of much of that two and one-half centuries of monastic experience and tradition. Benedict added a pure Gospel rendering and provided a form of monastic life that was the via media, a way of moderation between extremes. It was a livable form of monastic life that was created just at the time the Roman Empire was crumbling. Thus Benedict’s monastic lifestyle and his monasteries became a backbone of Western civilization, and the Benedictine monks saved much of classical culture—manuscripts and so forth. The sixth to the twelfth centuries are called by historians the Benedictine Centuries.

Benedict represents a kind of mainline monastic life. Both men and women have existed in Benedictine monastic life from the beginning because St. Benedict had a twin sister named St. Scholastica who had a convent nearby his monastery. Even when the Benedictines finally were sent to England by Pope St. Gregory the Great—St. Augustine—Benedictine nuns were established very early on the Isle of Thanet off of England. In that way the male and female branches of the Order have existed right from the beginning in the Benedictine tradition. In fact, this is true also of the older religious Orders in the Catholic Church: the Franciscans and Dominicans both have male and female branches, although as far as I know, there are no female Jesuits—yet.

The Benedictine way of life is a balanced life of prayer, work, and study. Benedict had the genius to provide a balanced daily rhythm of certain hours for prayer in common—the Divine Office or Liturgical Prayer—times for private prayer, times for study—a practice called lectio divina, a spiritual reading of the sacred text—and time for work. The Benedictine motto is ora et labora–prayer and work—although some people say it’s prayer and work, work, work! This balanced life is a key to the success of the Benedictine tradition. It has lasted for fifteen centuries because of a common sense, and because of an emphasis on Gospel values. Benedict had a great sensitivity for the old and the young, the infirm, the pilgrim. For example, an entire chapter of the Rule deals with hospitality and the reception of guests. One way the Benedictine motto has been described is that it is the love of learning and the desire of God. The Benedictines have a wonderful sense of culture and a great tradition of scholarship.

Women have been very important in the Benedictine tradition. Women like St. Gertrude and Hildegarde of Bingen, who have been rediscovered in the last five or ten years, have always been important in the Benedictine tradition. Earlier today when Venerable Thubten Chodron and I met, we discussed transmission and lineage, and although we in the West don’t have the master/disciple type of lineage that Buddhism has, we do have a kind of subtle transmission in the monasteries, a spirit that carries over from generation to generation. For example, an abbey of Benedictine nuns in England has a unique style of prayer which they trace back four centuries to Augustine Baker, the great spiritual writer. The nuns in this monastery pass this tradition on from one person to another. Monasteries are great reservoirs of spiritual power and spiritual knowledge in the tradition; they are a priceless resource.

In early Buddhism, monastics wandered from place to place in groups and were stable only during the monsoon season. Chodron told me she is continuing this tradition of wandering, even if it be by airplane! Meanwhile, the Benedictines are the only order in the Roman Church that has a vow of stability. That doesn’t mean that we have a chain and ball and have to literally be in one place. Rather, at the time Benedict wrote the rule in the sixth century, there were a lot of free lance monks wandering around. Some of them were not very reputable, and these were called the gyrovagues, or those who traveled around. Benedict tried to reform this by creating a stable monastic community. However, throughout the history of the Benedictines, there have been many who have wandered or who have been pilgrims. Even I have been on the road a lot for someone who has a vow of stability! The essential thing, of course, is stability in the community and its way of life.

My vocation and experience as a nun

I trace my vocation back to when I was in the eighth grade and my maternal grandmother unexpectedly died of a heart attack. I was suddenly confronted with the question, “What is the purpose of human existence? What is it all about?” I remember very clearly thinking, “Either God exists and everything makes sense, or God does not exist and nothing makes sense.” I reflected that if God exists, then it makes sense to live entirely in accordance with that fact. Although I was not going to a Catholic school and did not know any nuns, in a sense that was the beginning of my vocation because I concluded, “Yes, God exists and I am going to live entirely in terms of that.” Although I was a normal child who went to Sunday Mass, but not daily Mass, I really didn’t have much of a spirituality before this sudden confrontation with death brought me to question the purpose of human existence.

A few years later, in high school, I began to perceive a distinct call toward religious life and Benedictine life in particular. It was at this time that I felt the rising of desire for prayer and contact with that divine reality. In 1959, I entered an active Benedictine Community in Minnesota that engaged in teaching, nursing, and social work.

I have been a Benedictine for more than thirty years now, and I think it is a great grace and a wonderful experience. I have no regrets at all; it’s been a wonderful journey. At the beginning of my monastic life in Minnesota, I taught as well as lived a monastic life. As time went on I felt that I wanted to concentrate on my spiritual practice; I felt a call to contemplative life and didn’t know how I would live this out. For six years I taught high school, and then came to the east coast to study at Fordham. Increasingly I began to sense that living a contemplative life was the right thing to do, but before that was actualized I taught at St. Louis University for three years. I knew two sisters who were in Syracuse and intended to start the foundation from scratch in the Diocese of Syracuse, and I asked my community in Minnesota for permission to join them. But before doing that I decided that I should visit first, and so in 1978 drove from St. Louis to New York City, with a stop in Syracuse. On the Feast of the Transfiguration, I drove from Syracuse to New York City and on the way was almost out of gas. I pulled into the little town of Windsor, and as I drove down the main street, said to myself, “It would be nice to live in a small town like this.” The sisters had no idea where in the Diocese of Syracuse they were going to locate. Six months later I got a letter from Sister Jean-Marie saying that they had bought property in the southern tier of New York about fifteen miles east of Binghamton. I had a funny feeling that I remembered what town that was, and sure enough, it was Windsor. I believe the hand of God has been clearly guiding me along the way, specifically to Windsor.

After teaching graduate school in St. Louis for three years, I moved to Windsor to work with the other sisters to start a community from scratch, which is quite a challenge. Our aim is to return to a classical Benedictine lifestyle, very close to the earth, with great solitude, simplicity, and silence. Hospitality is a very important part of our life, so we have two guest houses. We are five nuns, and we hope to grow, although not into a huge community. We have a young sister now who is a very talented icon painter.

One privilege that I’ve had within the Order is that for eight years I was on a committee of both Benedictines and Trappists—monks and nuns—who were commissioned by the Vatican to begin dialogue with Buddhist and Hindu monks and nuns. In the mid-seventies, the Vatican Secretariat dialogued with the other major religions of the world and said that monastics should take a leading role in this because monasticism is a worldwide phenomenon. For eight years I had the privilege of being on a committee that began the dialogue with Hindu and Buddhist monks and nuns in the United States, and we sponsored visits of some of the Tibetan monks to American monasteries. In 1980, I was sent as a representative to the Third Asian Monastic Conference in Kandy, Sri Lanka, which was a meeting of Christian monastics in Asia. Our focus for that meeting was on poverty and simplicity of life, and also the question of dialogue with other traditions.

Spiritual formation

What is spirituality all about? To me, spirituality or the spiritual life comes down to one word—transformation. The path is about transformation, the passage from our old self to the new self, the path from ignorance to enlightenment, the path from selfishness to greater charity. There are many ways that this can be talked about: Hinduism talks about the ahamkara, the superficial self, and the atman, the deep self that one attains through spiritual practice. Merton talked about the transition or the passage from the false self to our true identity in God. The Sufi tradition discusses the necessity of the disintegration of the old self, fana, and ba’qa, the reintegration in a deeper, spiritual self. I am not saying that all of these are identical, but they are certainly analogous, even homologous. Tibetan Buddhism talks about the vajra self, and it is interesting that Theresa of Avila in The Interior Castle describes going inward to the center of her soul through steps and phases of spiritual practice. She said, “I came to the center of my soul, where I saw my soul blazing up like a diamond.” The symbol of the diamond, the vajra, is a universal or archetypal symbol of spiritual transformation. The diamond is luminous—light shines through it—and yet it’s indestructible. It is the result of transformation through intense pressure and intense heat. All true spiritual transformation, I believe, is a result of spiritually intense pressure and intense heat. In the Book of Revelation, chapter 22, there’s a vision of the heavenly Jerusalem which is the consummation of the cosmos or the consummation of our individual spiritual journey. The writer of the Book of Revelation describes a mandala: “I saw the vision of the city, a twelve-gated city and in the center was the throne with the Lamb on it, the Father/Son, and a river of life flowing in four directions, the Holy Spirit.” This is the Christian trinitarian interpretation. As the author of the Book of Revelations describes it, the waters were crystal or diamond-like. That light of the grace of God, the divine, the ultimate that transforms us is that crystal light, that diamond-like luminosity that shines through us. We chose to name the monastery at Windsor Monastery of the Transfiguration, because we believe that monastics are called to be transformed themselves in order to transform the cosmos; to transform not only ourselves, but the entire world; to let that light, that luminosity, radiate out from us to all of creation.

Another way that the Tibetan Buddhists talk about enlightenment is the intermarriage of wisdom and compassion. I’ve thought about this, and may be stretching your meaning of it a little bit, but I think that in each human being there is a tendency towards love and a tendency towards knowledge. Those basic virtues, those instincts in us, must be transformed in order to complete love and knowledge. Our love is like the anima that must become animus, and our knowledge is the animus which must become anima. That is, our knowledge must become wisdom by becoming loving, and our loving must become wise in order to be transformed. I believe that we can identify that process leading to the intermarriage of wisdom and compassion in all the great paths of holiness.

I haven’t said much about women and women’s experience, but we’ll get to that in the discussion after our presentations. Venerable Thubten Chodron and I certainly had some interesting discussions about it today at the monastery! I believe scholars have found that perhaps the first evidence of any sort of monastic life was with the women who were Jains in India. Perhaps the first monastic life in history that we know of was a women’s form of monastic life.