Nonviolence and compassion

A student responds to Venerable Thubten Chodron's recent talk, "Our game plan in a time of war."

Dear Venerable Chodron,

Thank you for your excellent and (thorough!) Dharma talk “Our Game Plan in a Time of War.” It was much needed medicine in this moment. I especially appreciated how you tied the complicated history of the previous wars, NATO, and other causes and conditions together in trying to understand both the facts of history and Putin’s perspective. This was a great example for me of the path to reconciliation that I hope diplomats and politicians will also take, to be able to see not only history but to see from both sides and understand the other’s “side,” and it helped me to see and hear you do this at a time when there is so much dogmatism and reactive expression of hate based on the very understandable anger and fear going on in media and elsewhere.

Just the other day I had read this essay from His Holiness on “The Reality of War,” which I thought expressed the issues at hand very well. In it, His Holiness talks about the question of how to respond to aggression, which also came up during the questions in your talk, and toward the end he mentions examples. The beginning of it is a powerful description of the truth of war, the kind of truth telling we need now when many well-intentioned people seem to be almost entertained by the spectacle of war. His Holiness writes, “In fact, we have been brainwashed. War is neither glamorous nor attractive. It is monstrous. Its very nature is one of tragedy and suffering.”

On that same issue, I had also recently been reading Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who wrote in 1960 that due to the destructive power of modern weapons, he had changed his own position on this question:

“More recently I have come to see the need for the method of nonviolence in international relations. Although I was not yet convinced of its efficacy in conflicts between nations, I felt that while war could never be a positive good, it could serve as a negative good by preventing the spread and growth of an evil force. War, horrible as it is, might be preferable to surrender to a totalitarian system. But now I believe that the potential destructiveness of modern weapons totally rules out the possibility of war ever again achieving a negative good. If we assume that mankind has a right to survive then we must find an alternative to war and destruction.” (“Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” from Strength to Love, 13 April 1960)

During your talk when you mentioned Shantideva I was also reminded of Thich Nhat Hanh’s words: “Our real enemy is not man, is not another human being. Our real enemy is our ignorance, discrimination, fear, craving, and violence” and his related question, “Men are not our enemies, if we kill men with whom shall we live?” There is a striking photo of Martin Luther King marching under a banner with that question on it, in both English and Vietnamese.

Again on the question of nonviolence, I had read this passage below and it came to mind when I heard the specific question that came up of how we should deal with nonviolence when we’re in danger, or during invasion, whether it’s moral to fight back or not. This is from Thich Nhat Hanh’s newest book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet where there is a section called “The Art of Non-Violence” in which he writes:

“The word ‘non-violence’ may give the impression that you’re not very active, that you’re passive. But it’s not true. To live peacefully with non-violence is an art, and we have to learn how to do it. Non-violence is not a strategy, a skill, or a tactic to arrive at some kind of goal. It is the kind of action or response that springs from understanding and compassion. As long as you have understanding and compassion in your heart, everything you do will be non-violent. But, as soon as you become dogmatic about being non-violent, you’re no longer non-violent. The spirit of non-violence should be intelligent. […]

“Sometimes non-action is violence. If you allow others to kill and destroy, although you are not doing anything, you are also implicit in that violence. So, violence can be action or non-action. […]”

“Non-violence can never be absolute. We can only say that we should be as non-violent as we can. When we think of the military, we think that what the military does is only violent. But there are many ways of conducting an army, protecting a town, and stopping an invasion. There are more-violent ways and less-violent ways. You can always choose. Perhaps it’s not possible to be 100 percent non-violent, but 80 percent non-violent is better than 10 percent non-violent. Don’t ask for the absolute. You cannot be perfect. You do your best; that is what’s needed. What is important is that you’re determined to go in the direction of understanding and compassion. Non-violence is like a North Star. We only have to do our best, and that is good enough.”

And a final line from bell hooks that I had also recently read in her book All About Love which came to mind after your talk was sinking in: “In a world anguished by rampant destruction, fear prevails. When we love, we no longer allow our hearts to be held captive by fear.”

Thank you again for taking time to share this talk with us all. Thank you for your words, and practice. Wishing you and all at the Abbey joy, peace, and freedom.

Michael

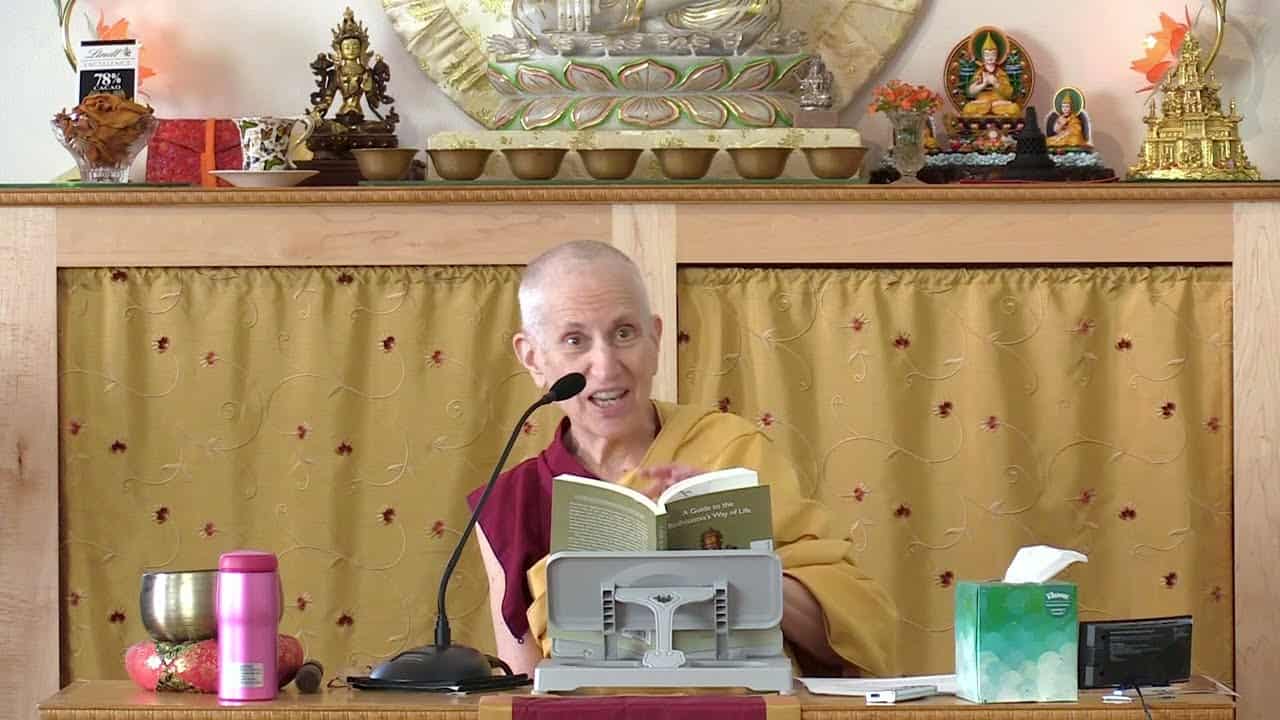

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.