Generating the awakening mind

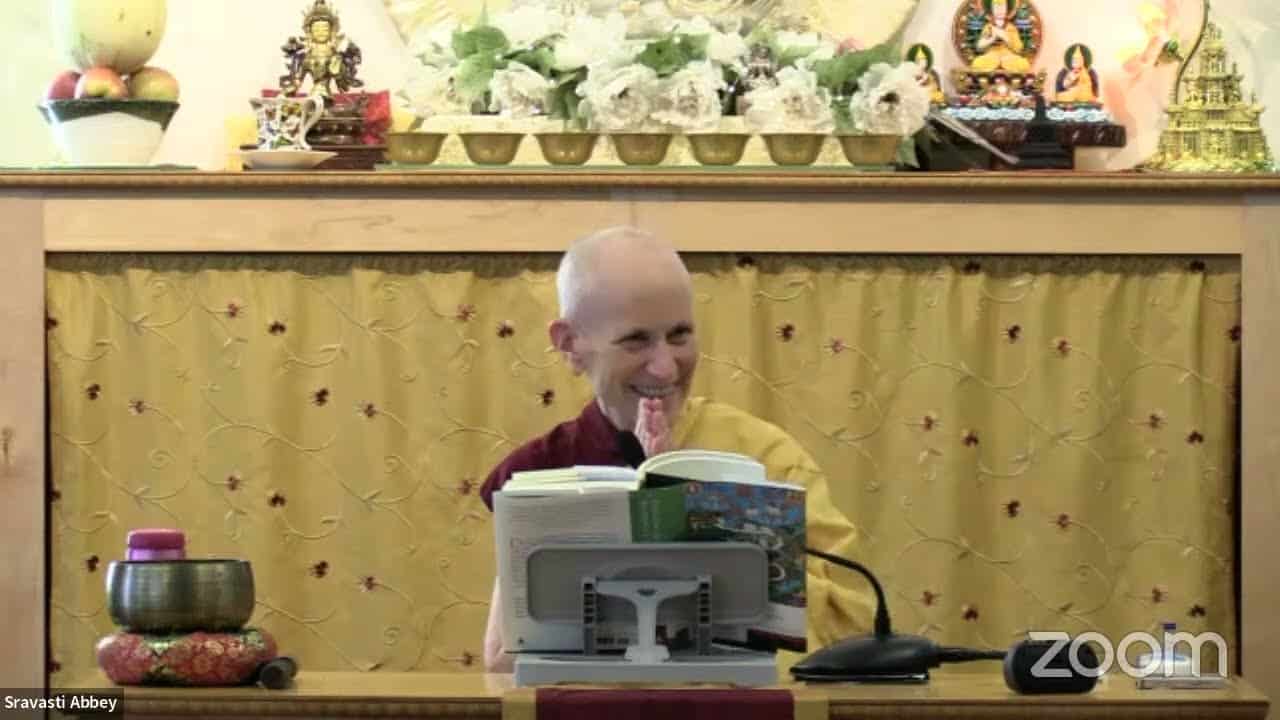

05 Commentary on the Awakening Mind

Translated by Geshe Kelsang Wangmo, Yangten Rinpoche explains A Commentary on the Awakening Mind.

We ended last time with verse 72:

Those who do not understand emptiness

Are not receptive vehicles for liberation;

Such ignorant beings will revolve

In the existence prison of six classes of beings.

This text describes selflessness, and without understanding that subtle selflessness, that subtle emptiness of phenomena, we cannot attain liberation. That’s what it means when it says, “Such ignorant beings will revolve in the existence prison of six classes of beings.” The root of cyclic existence is ignorance. That doesn’t just refer to the mind that’s grasped by the self, but also the grasping at signs, grasping at characteristics and so forth. All these are part of the root ignorance, and without overcoming that, we cannot overcome cyclic existence. In the first chapter of Lama Tsongkhapa’s Entering The Middle Way, there are three kinds of reasonings to establish why heroes and solitary realizers realize emptiness. Because if they didn’t realize emptiness, there would be three contradictions. This is similar here; this is connected to or related to that. In order to understand this, you have these three reasonings from Entering The Middle Way.

Likewise, in the special insight section of the Lam Rim Chen Mo by Lama Tsongkhapa, this is also explained. So, the question arises: “In order to overcome samsara, do I have to realize emptiness or not?” Do we have to realize the emptiness of phenomena, the subtlest type of emptiness of all phenomena? Lama Tsongkhapa talks about this. Also, in Ayadeva’s 400 Stanzas on the Middle Way, and in the commentary by Chandrakirti on the 400 Stanzas, they both explain the same thing. It’s not like Chandrakirti gives a different explanation. If it were different then that would mean that one didn’t have to realize the subtlest type of emptiness that is free from all mistaken appearances or all mistaken perceptions. If there were a different explanation then that could mean that you didn’t have to realize emptiness to become liberated. However, that’s not the case. Chandrakirti explains it the same way in Entering The Middle Way and in his commentary on the 400 Stanzas.

There are many different reasonings. For instance, there’s the reasoning that something doesn’t arise from a cause that is totally different or from the same cause; it doesn’t arise from both; and it doesn’t arise without a cause. And then there are other reasonings, such as dependent origination. All these are reasonings establish the lack of inherent existence. And that’s what we need to realize, because if we do that, then once we realize emptiness, we can also overcome the other afflictions. This is something we need to think about again and again. Now, when we say self-grasping, what is this self-grasping? It’s a mind that holds on to the true existence of the self. And this self-grasping mind then induces afflictions, such as anger, aversion, attachment and so forth. So, how does the mind that realizes emptiness actually harm these afflictions, such as aversion and attachment? This is something we really need to think about. (Translator: This verse that Rinpoche just read is connected to a lot of other texts that we should analyze and investigate.) But anyway, we’re not going into all these different texts; we don’t have time. We’ll just go through the verses here. For more on this, though, you can see the Six Collections of Reasonings, and the special insight section of The Middle Length Lam Rim.

Stages of self-grasping: the analogy of a snake

What is the root of samsara? What is it that we need to overcome? What is it we have to overcome in the sense that if we don’t overcome it then we won’t be able to overcome samsara? What is this ignorance? If we pay some attention to that then we will get a good understanding of all the texts, of all the scriptures. It will be beneficial in that way, I think. So, attachment and aversion—how do they arise from self-grasping? How does self-grasping give rise to them? I would like to talk about this. I’ve spoken about this before a little bit.

When talking about self-grasping, there’s an example that is usually cited. Right now it’s very light, but when the light fades in the evening, you can’t really see as clearly as you would see at midday, for instance. So, for this example, say it’s not totally dark but you can’t see clearly, and then you see a speckled rope in the shape of a snake’s body. Say someone threw it in the road, and it formed the wavy body of a snake. It’s almost dark, but you can still see. When you walk on that street at that time, there’s the thought that there is really a snake. “There’s a snake over there”: this thought arises. The person who thinks that perceives a snake. There’s a sense that from the side of this object, there is a snake. In the mind of that person perceiving the snake, there’s something objectively over there. This speckled rope in our mind appears as a snake, but where is that snake? It’s objectively over there, where this speckled object is. It seems there’s really, truly something there. That’s how it appears to our mind. There’s a sense that it’s really over there, that there’s really this object there. There’s really a snake. This is true especially when it’s someone who’s afraid of snakes. In the case of that person, there’s this real snake over there.

Actually, there’s no snake over there. But we have this strong thought. Is there really a snake? No, there’s no snake at all. There’s not even an atom of a snake over there. So, we can say a hundred percent that this is merely designated by thought. But it seems that although it’s just labeled by the mind, by thought, by conceptual consciousness, there’s something from the side of the object. It seems that the object exists objectively as a snake. The sense that it’s a hundred percent coming from the object—this snake—that’s the sense to the mind. It’s as if it existed from its own side. So, it appears clearly to our mind; it appears directly to our mind. There’s a sense that there’s a direct perception of an actual snake. That’s how it feels. There’s no sense that our mind just fabricated that. No, it seems it all comes from the side of the object.

We might think, “If a snake bites me then I will die right away. The poison will kill me.” All these extreme thoughts—these inappropriate attitudes as they’re called—are minds that exaggerate. “Oh, I’m going to die. I’m going to have so many problems”—and so forth. A lot of negative thoughts arise: “It’s so dangerous. It’s so terrible. It’s worse than samsara. This is worse than anything that can happen.” What happens in these cases is that our mind arises in the form of this extreme, exaggerating attitude and just sees it as so negative, so terrible, and so fearful. It’s this attitude that exaggerates negativity of the object. And then that extreme mind gives rise to fear. It gives rise to this incredible fear, this panic—you feel real terror because of seeing this snake. This really scared mind arises from this exaggerating attitude.

So, first we don’t perceive the rope as a rope; we instead perceive it as a snake. That’s the first step. When we see this rope, our mind fabricates a real snake. Actually, it doesn’t exist over there, but there’s a sense that “Oh, there’s a real snake just over there.” We perceive it to be objectively over there, without realizing that it’s just fabricated by the mind. Some people like snakes, and some people even eat snakes. Therefore, although it’s still just fabricated, they have the sense that “Oh, that’s wonderful” or “Maybe I could eat some snake. It’s so beneficial. It would be so delicious,” and so forth. So again, the mind fabricates, the mind imputes, the mind designates it’s being delicious and so forth. Then the mind exaggerates: “Oh, this is so wonderful; this is so delicious.” Again, the exaggerating mind arises, but this time it exaggerates the positive aspects, which gives rise then as the third step to attachment: “I can drink the blood of this snake. I can eat its meat, its flesh,” and so forth.

Where did it come from? The first step was this misperception, this sense that there’s an objective snake over there. That was the first step: giving rise to the extreme attitude and then to attachment. And sometimes people get angry. Some people have aversion toward snakes. Again, it’s similar. What first appears is this rope, but on the basis of that, this misperception of a snake arises, and then this extreme attitude arises. This extreme attitude is generated, this feeling of “That’s so terrible; that’s such a horrible thing.” They are seeing it as totally negative, which then gives rise to aversion, gives rise to anger.

In all these cases, the first step is perceiving this object over there. So basically, what’s actually there is this rope, but this rope is perceived to be a real snake. It’s fabricated. The mind labels “snake,” and believes it to be objectively there. If we were to see the rope right from the beginning then all these extreme minds wouldn’t arise. The exaggerating attitude and so forth would not arise. As I said earlier, in the case of the snake, aversion and attachment can only arise because there’s this mind that fabricates this true existence. Perceiving there to be an objective snake gives rise to the extreme attitude, and that extreme attitude then induces all the other afflictions. For some people, it’s attachment. For other people, there’s anger. Sometimes there is even arrogance: “Oh, I don’t need to be scared of some kind of snake. I’m so much stronger than this snake.” Arrogance may also rise as a result of this scenario. But, in all cases, the first mind that arises is this mind that fabricates or that feels there’s a truly existent snake.

Actually, there’s no snake at all. It’s only created by the mind. It just appears to the mind. There’s not a single atom of a snake over there. The mind just labeled it and then that gave rise to this sense of an inherently existent snake. It doesn’t exist truly on the basis of this rope. Similarly, to our mind there appears to be a self, so we label “self.” And based on that, we then come to believe that there’s a truly existent I. But in the same way as there’s no truly existent snake, there’s also no truly existent I. Just as the snake cannot be found in this example, likewise, the self cannot be found somewhere as part of the aggregates. In relation to the aggregates, it cannot be found. So, these two examples are similar in that just as there’s no snake that exists beyond being merely labeled, there’s no I that exists beyond being labeled. This example is very beautiful.

In this example, we have the perception of a snake because it’s not very light out, and we can’t see clearly. This is similar in our case. The slight darkness is like our ignorance. Just like this slight darkness affects our perception, so our ignorance also affects our perception. In that way, they’re similar. There are similarities between the example and that which the examples describe. Now, in the case of the snake, not only do we have ignorance, but we also come to understand that first there’s this imputation—the labeling—and then there’s the ignorance. So, that gives rise to this. That’s the sense that a snake is truly there, that it exists by way of its own character and so forth. Likewise, this also happens when it comes to the self. We label the self, and then we perceive that to be a truly existent self. These two are similar in that case. When we label something then we perceive it. After that, we perceive it to exist truly.

It’s based on cause and effect: there’s a cause that gives rise then to the misperception that gives rise to the afflictions and so forth. Similar to the example here of the snake and the rope, when we perceive an object, because of our ignorance, we perceive things in a mistaken way. We perceive things to exist truly, to exist objectively. So, if we think about the example and that which it describes, it may be beneficial.

Meditating on emptiness gives rise to compassion

Then verse 73:

When this emptiness [as explained]

Is thus meditated upon by yogis,

No doubt there will arise in them

A sentiment attached to others’ welfare.

When we directly meditate on great compassion, we think of the suffering of other sentient beings and reflect on the fact that other sentient beings don’t want to suffer, that they want to be happy. Also, we think that they’re just like me; we all want to be happy and free from suffering. All sentient beings are like myself in that way. There’s no difference in that. We all want to be free from suffering. We all want to be happy. This is true for all of us. So, we share this intuitive kind of wish to be free from suffering. And then based on that, it gives rise to love. There are different techniques for generating love and compassion, such as Equalizing and Exchanging Self and Others and the Seven-Point Cause and Effect. Whichever technique we follow, we don’t perceive sentient beings as totally disconnected to us. We have a sense that we’re very connected to every sentient being, that they’ve been really kind to us in the past, and that they’re very kind to us now. On the basis of these two techniques, we’re able to generate that closeness.

For instance, we talk about recognizing all sentient beings as having been our mother, having been our father, and then recognizing that kindness, wanting to repay that kindness, and so forth. It doesn’t have to be our mother; we can focus on anyone who’s been extremely kind to us. The important thing is to focus on the fact that someone has been so kind to us. We remember that time and again, they’ve done so much for us. Once we are remembering that kindness, once we reflect on that kindness, then the wish arises: “May I be able to benefit or may I be able to repay that kindness.” Therefore, when this emptiness is explained and we meditate upon it, no doubt there will arise in us a sentiment attached to others’ welfare. That’s what this verse is talking about: meditating on emptiness will give rise to compassion.

How do we do this? First of all, we all have grasping at the self. We have self-grasping. We are under the control of this ignorance, and we are under the control of the other afflictions. We have so many problems, so many difficulties. And this is the same for others. We are impaired by ignorance. Because of ignorance, our eyes of wisdom are not functioning, so we are sightless—us and all sentient beings. We have to understand this. Then when we understand emptiness, we also get a sense that all sentient beings, especially those who are uncontrollably reborn in samsara, are sightless. They don’t see. They are these poor beings who are caught in samsara, who have no freedom. And these poor beings have no control. There is nothing they can do. And then compassion arises. In that way, compassion develops by thinking of emptiness; it’s because of emptiness. On the basis of an understanding of emptiness, then we can really generate compassion. So, emptiness is very powerful here. This is what it says here: that emptiness can really help us to generate more compassion.

Everything we have depends on others

Verse 74:

‘Towards those beings that have

Bestowed benefits upon me in the past,

Such as through being my parents or friends,

I shall strive to repay their kindness.‘

This verse is talking about the Seven-Point Cause and Effect Instruction, this one technique for generating love and compassion. Everyone has been my parent, my friend. They have been so close to me in the past. So many times in the past, sentient beings have benefited me so much. And in this case, we have to also remember that our mind is a continuum that has no beginning and no end. It’s a clear and knowing mind that has always existed. And so when our body and our mind separate, then we go on to the next life. We take on a new body. And so this has happened since beginningless time. Therefore, there’s been no beginning to us having had parents. There’s no limit to the number of parents we’ve had. We’ve never been separated from sentient beings. Even in the present, everything we have right now comes from other sentient beings: our education, our health, the food we get every day, our physical well being, the place we stay at, our house. Everything comes from other sentient beings. Even our life is dependent on other sentient beings—on their kindness, their love, and so forth.

If we didn’t have any faith in others, if we didn’t trust others, if we didn’t have any connection with others, we wouldn’t have a life. We wouldn’t be able to survive. If I were to not trust anyone, and if I didn’t want to be with other people, then I’d really have a problem. There are eight billion people on this planet, so if I were to just live on my own, it would be difficult. If I were to live in some kind of isolated place where there are no sentient beings, I wouldn’t survive. So, with this technique, we reflect on the fact that without others I couldn’t be here. I need a place to sleep, I need the sun, I need oxygen, I need all these objects, I need the four elements, but more than all of that, I need sentient beings. It’s actually the foundation from which everything comes. Sentient beings are like a wish-fulfilling jewel because I get everything from sentient beings. It’s always the case that I have to rely on sentient beings. I have to rely on society. Look around you: everything comes from other sentient beings—even this building we’re in right now.

In this building there’s a fan, so there’s a way to cool us down. Who made this fan? It was people. There’s a factory that created it, there were people who designed it, there are people who put the parts together, and there are people who created the parts. There are so many people involved in the process of just making a fan. And then we should also reflect on past lives. We have had so many different relationships. Everyone has been related to us. They have been our parents. They have been so close to us at some point. When we say “sentient beings,” we’re talking about society in the sense of the community of living beings. So actually, when we compare that to the kindness of our mother in this life, sentient beings have been much, much kinder.

Repaying the kindness of others

Verse 75:

‘To those beings that are being scorched

By the fires of afflictions in existence’s prison,

Just as I have given them sufferings [in the past],

It’s befitting [today] that I give them happiness.‘

We need to think of all sentient beings having been so kind to us, which leads to wanting to repay that kindness. So far, I’ve just given problems to people. We’ve lived in samsara for so long, and due to our self-centeredness—“I need this; I don’t need that,” and so forth—we’ve created problems for others. I’ve harmed sentient beings, so from now on, I should start to give them happiness. This happens by first having the thought “May they have happiness,” and then acting accordingly. We work towards this. Our attitude should be such that we want them to be happy, and our actions should be based on that attitude. This is the technique of the Seven-Point Cause and Effect Instruction.

Verse 76:

The fruits which are desirable or undesirable

In the form of fortunate or unfortunate births in the world,

They come about from helping the sentient beings

Or harming them.

If we help sentient beings, if we benefit sentient beings, then we will experience a fortunate birth. If we harm them, we will experience an unfortunate birth. There’s like this connection between this. When we benefit sentient beings, we’ll find happiness. If we harm sentient beings, we also experience harm. Suffering arises as a result of harming others. Isn’t that amazing? So, if I benefit another person, I gain the benefit. The attitude is “I want to benefit the other person,” but actually I get the benefit. Isn’t that amazing?

Consequences of helping or harming

Verses 77 and 78:

If by relying upon the sentient beings

The unexcelled state [of Buddhahood] is brought about,

So what is so astonishing about the fact

That whatever prosperities there are in the gods and humans,

Such as those enjoyed by Brahma, Indra and Rudra,

And the [worldly] guardians of the world,

There is nothing in this triple world system

That is not brought forth by helping others?

In this samsara, there are these beings who have great power. There are humans, but there are also celestial beings, such as Brahma, Indra and so forth. But there’s nothing in this triple world system that is not brought forth by helping others. So, we consider other sentient beings as our life—we respect others, consider them to be precious, rely on them. We have this closeness and a sense that this community of sentient beings is so precious. And if we generate love and compassion and forbearance and so forth, then by really having this love and compassion for other sentient beings, ultimately we will also reach Buddhahood. No matter what human or celestial enjoyments there are, such as being Brahma, Indra or Rudra, if we have the attitude of benefiting others, we can also reach these states. We will be reborn as gods and humans. That would be possible. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t be. If we can become fully enlightened by benefiting others, we can definitely achieve these higher states in samsara—becoming powerful celestial beings or humans and so forth. There’s nothing astonishing about this. If we can even attain Buddhahood by relying upon sentient beings, there’s nothing astonishing about the fact that we can take on these great states.

Then verses 79 and 80:

As hell beings, as animals and as hungry ghosts,

The different kinds of sufferings,

Which sentient beings experience,

These come about from harming others.

Hunger, thirst, and attacking each other,

And the agony of being tormented,

Which are difficult to avert and unending—

These are the fruits of harming others.

Hell beings, animals and hungry ghosts have so many different kinds of sufferings. Hunger and thirst is referring to the preta suffering or the hungry ghost suffering. Attacking each other refers to animals; animals attack each other. So, hunger and thirst is the suffering typical for the hungry ghosts, and attacking each other is typical for animals. For instance, birds eat worms, and they feed their offspring by killing worms. There are some birds like eagles and other types of huge birds that kill other animals. They steal the eggs from other birds and then suck out these eggs to feed their own offspring. Sometimes these birds actually seem to be very clever. They put the eggs somewhere else. (Translator: I think what Rinpoche is explaining here is that there are really clever birds that put their eggs somewhere else because they know someone else will come and steal them.) So, they’re really, really clever in the way they deal with the eggs and their offspring and so forth. But that’s what animals do: they attack each other, and they experience the agony of being tormented and so forth.

Then verse 81:

[Just as] there is Buddhahood and awakening mind

And the fortunate birth [on the one hand]

And the unfortunate birth [on the other],

Know that the [karmic] fruition of beings too is twofold.

When we accumulate something positive then the result is something positive. So, Buddhahood and awakening mind, fortunate and unfortunate births—they all come from other sentient beings. An unfortunate rebirth is the result of harming other sentient beings. When it comes to harming and benefiting sentient beings, you have two types of results. So, the real question is: how do I rely on sentient beings? How can I respect them? How can I consider them to be precious? How can I look after them? That is explained in the next verse.

How to rely on other beings

Verse 82:

Support others with all possible factors;

Protect them as you would your own body.

Detachment towards other sentient beings

Must be shunned as you would a poison.

We should give everything if we can. Whatever we have, we should give. Let it go for the benefit of all sentient beings. We need to rely on other sentient beings in that way. We should protect them. We should consider them to be really precious. Asanga says that a bodhisattva’s generosity is such that it’s very effective and very intelligent. So, generosity should be practiced with wisdom. Giving everything to sentient beings is not what generosity is all about. We need to be clever. We need to be intelligent when we practice generosity. Giving everything—our food, our drink, everything—and becoming beggars ourselves is not what it means to be generous. For instance, we don’t need to give up our body when someone asks us to give our body. We need to have a certain degree of compassion before we can actually give up our body. It’s not okay to just give it away. Even if the other person wants our body, there needs to be a specific necessity. There are cases when giving up our own body is not as important. If giving up our body versus keeping our body is more beneficial, then it’s okay to give up our body.

And the same is true with regard to objects. We need to reflect: “Is it suitable to give this away or not?” There’s a lot of reflection required. Our attitude, the time, the situation—all this needs to be considered before we practice generosity. For instance, if you give food to a bhikshu after lunch—if you give them dinner—that is not appropriate. That is not considered to be an appropriate or suitable object of offering. If you give someone who is a drug addict money, then again, it’s not appropriate. It’s not an appropriate type of generosity because they continue with their habit. In that way, it’s important to understand the situation when we give something, and to give something that is appropriate, that’s really beneficial. If we have a lot of things, then of course we can give. But whatever we can give, it should be given with intelligence in order to benefit other sentient beings. We shouldn’t let go of sentient beings. We shouldn’t be attached to sentient beings, but detachment is not the right kind of attitude. We should protect them. Detachment is like poison.

Verse 83:

Because of their detachment,

Did not the Disciples attain lesser awakening?

By never abandoning the sentient beings

The fully awakened Buddhas attained awakening.

If we don’t have that strong feeling towards sentient beings, then there’s a lesser awakening. We have to consider sentient beings to be more important than ourselves. If we don’t have that attitude, then the liberation we attain is of a lesser kind. But if we never abandon sentient beings, if we feel very close towards them and consider them to be extremely important, then the fully awakened state of a Buddha is attained.

Verse 84:

Thus when one considers the occurrence of

The fruits of beneficial and non-beneficial deeds,

How can anyone remain even for an instant

Attached [only] to one’s own welfare?

How do we benefit from this, and how do others benefit? If we benefit others, how does it benefit us? When we harm others, how does it harm us? If I have just for one second the thought “May all sentient beings find happiness,” then just in that short moment of having this thought, the merit is limitless. Why? Because my focus is all sentient beings that are limitless. So, if I have the thought “May they all be happy; may they be free from suffering,” it’s a thought that is as expansive as space. It’s as limitless as space because it’s focusing on limitless sentient beings. And whose kindness is that? It’s other sentient beings. It’s just through their existence that they give us the opportunity to have these beneficial thoughts. So, when we benefit them, we should benefit them in an expansive way. If, on the other hand, if we let go of all sentient beings and just think selfishly, then it’s impossible to do. It only harms us if we just totally let go of sentient beings and just act for our own benefit. It’s important to accumulate so much merit in each moment. Therefore, even a little merit is important. We shouldn’t give this opportunity up. It’s just one second, but one second gives us such an opportunity to just think of all sentient beings. How can anyone remain even for an instant attached only to one’s own welfare?

The courage of a bodhisattva

Verse 85:

Rooted firmly because of compassion,

And arising from the shoot of awakening mind,

The [true] Awakening that is the sole fruit of altruism—

This the conqueror’s children cultivate.

So, that is the root cause of the awakening mind. It’s kind of like the shoot of the awakening mind. In dependence on compassion then the awakening mind arises, bodhicitta arises. Once we have the awakening mind, once we have bodhicitta, then that’s the sole fruit of altruism. For the benefit of others, we will work towards becoming a buddha. That’s the bodhisattvas’ aim. They aim towards the benefit of all sentient beings. And on the basis of that—wanting to benefit sentient beings—buddhahood is achieved.

Verse 86:

When through practice it becomes firm,

Then alarmed by others’ suffering,

The [bodhisattvas] renounce the bliss of concentration

And plunge even to the depths of relentless hells.

This is really showing the incredible determination of bodhisattvas. When the awakening mind has arisen—when it’s unchangeably there, without degenerating—then bodhisattvas are alarmed by others’ sufferings. When bodhicitta is very firm and stable then we take on the suffering of others. We’re happy to take on the sufferings of others in order to free them from that experience. We’ll be happy to take on the suffering. For the benefit of others, we sacrifice ourselves as much as we can. So, we’ll be happy, we’ll be blissful, to take on others’ sufferings so that they don’t have the experience. And this is much greater than the bliss of concentration. They’re even able to renounce this incredible bliss that bodhisattvas could experience. They’re able to sacrifice that, to give it up. And instead, they’ll be plunged even to the depth of the horrendous hell—the worst kind of hell. On the basis of wanting to take on the suffering of other sentient beings, a bodhisattva would give up the greatest bliss just to be able to experience the suffering of even the relentless hell in the place of someone else. That’s the kind of attitude bodhisattvas develop on the basis of their awakening mind.

When we benefit all sentient beings, this kind of attitude is so expansive. It’s so vast, so extensive. First we can’t have these vast thoughts; we can’t think of all sentient beings. It’s actually a difficult quest. So, for example, say I’m going to clean this environment. I’m cleaning this place. Actually, we can start off with the attitude of “I’m sweeping the ground for the benefit of all sentient beings.” That’s how we can start: “May this act of sweeping the ground be of the benefit of all sentient beings.” And from there, we can extend it. Incredible inner strength and courage arises when we do this. Eventually, there’s a sense that for the benefit of all sentient beings, I’ll work hard. It doesn’t matter how hard. In the beginning, this hardship of sweeping, of cleaning, is done for the benefit of other sentient beings. But later on, I can do even more difficult tasks. I can do all sorts of things just for the benefit of sentient beings. So, there’s no sense of harm or there’s no sense of toil in that moment.

It doesn’t feel like hardship when I do it for the benefit of other sentient beings. It’s not felt as if we’re suffering. I’m not suffering because I’m working for the benefit of sentient beings. It’s not seen as hardship. Take the example of some people who are very patriotic. They’re always working for their own country. A soldier, for instance, who’s very patriotic would go to war for their country. That’s seen as something magnificent. It’s seen as something important. Say they lose their limbs because of a bomb. That’s an incredible problem if you think about it, but they did it for their country. So, when they come back, they have a sense of “I did this for my country. I sacrificed my arms and my legs when they were torn off by a bomb.” For some people, it’s like, “I’ve done my very best, so there’s no regret.” They feel proud of what they’ve done—of their achievement. They don’t consider that to be a problem. They don’t consider this to be hardship because they did it for their country.

When you’re so patriotic and you do this for your country, and you’re able to sacrifice everything, then you don’t see it as hardship. It’s seen as something precious, as something magnificent. They like it even—that they have the opportunity to do this for their country. It’s some kind of pride: you did it for others; you did it for your country. Likewise here, taking this as an example, we’re doing this for the benefit of all sentient beings. We’re doing it for all humans in this world, but not just all humans; we’re doing it for all living beings of the world, of the universe. That’s why we’re doing this. We’re doing this for all sentient beings. That’s why the Buddha said that if we consider only one particular entity—in this case ourselves—to be extremely important, then whatever we do will be mistaken. But if we don’t just focus on one being, but on all sentient beings instead—if we don’t harm others and we benefit other sentient beings—then everything we do will be non-contradictory. It will be in accordance with reality if we act like that. That’s what the Buddha said. If we think of all sentient beings then we don’t contradict reality.

It’s different if we just think of ourselves and consider ourselves to be most important: “It benefits me. It may harm other sentient beings, but I don’t care.” If we just focus on ourselves—“It will help my country or my race or my community, and it harms everyone else, but I don’t care”—if we have that attitude that is partial, and we distinguish between sentient beings, then we will also not live in harmony. Basically, the harmony of society is disrupted. If we just think of ourselves, the harmony of society is disrupted. Also, if we think of just certain groups then society can’t live together in harmony. That leads to a lot of conflict, so it ends up that we build a lot of atomic bombs, that different countries produce all these atomic bombs or nuclear weapons. But why?

The thought is like, “I will destroy those others to protect myself.” That’s the kind of attitude people have, an attitude of “My country versus others’ countries.” There’s a vast difference between this attitude and the attitude of a bodhisattva. The great bodhisattvas let go of even the bliss of concentration for the benefit of the sentient beings. Whatever suffering they have to experience, it doesn’t matter. Even if they have to plunge into the depth of relentless hell, or the relentless hell state, they will do so with joy. They do so with happiness for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Verse 87:

This is indeed amazing, praiseworthy it is;

This is the excellent way of the sublime;

That they give away their own flesh

And wealth is not surprising at all.

There’s nothing greater than the conduct of a bodhisattva, so this is the conduct of a wise person. It’s amazing, praiseworthy and so forth. If someone really plunges into the relentless hells for the benefit of others, then giving their body is nothing amazing actually. In that case, giving away some wealth, that’s not surprising. That’s not so great. Of course giving our flesh is amazing, but plunging into hell is really amazing.

Emptiness and the law of karma

Verse 88:

Those who understand this emptiness of phenomena

Yet [also] conform to the law of karma and its results,

That is more amazing than amazing!

That is more wondrous than wondrous!

On the basis of understanding emptiness, we still conform to the law of karma and its result—we really act according to the law of karma and its result. In the sense that our understanding of emptiness does not contradict the law of karma and its result, they’re both seen as fitting. They both make sense. Although phenomena lack inherent existence, the law of karma and its result is valid. In fact, it exists because phenomena lack inherent existence, so basically, the understanding of emptiness supports our understanding of the law of karma. And from the point of view of wisdom, that is more amazing than amazing. That is more wondrous than wondrous. We talked about the method aspect previously—working for the benefit of other sentient beings, benefiting them. This is talking about the quality of wisdom. And our wisdom benefits our method, so if we have extensive wisdom then we have extensive method.

Wisdom realizing emptiness conjoined with bodhicitta

Verse 89:

Those who wish to save sentient beings,

Even if they are reborn in the mires of existence,

They are not sullied by the stains of its events;

Just like the petals of a lotus born in a lake.

A bodhisattva is reborn in samsara for the benefit of all sentient beings. They’re reborn in the mires of existence, but they’re not sullied by the afflictions. They’re just like the petals of a lotus born in a lake. And then the reason is given in the next verse.

Verse 90:

Though bodhisattvas such as Samantabhadra

Have burned the wood of afflictions

With the wisdom fire of emptiness,

They still remain moistened by compassion.

Again, this is the reason explaining verse 89: the bodhisattvas such as Samantabhadra have burned the wood of afflictions. So, it’s the internal afflictions. Due to having realized emptiness, that is very stable in their continuum, and they’re awake. This is the mind realizing emptiness that is conjoined with bodhichitta. This is so stable that it cannot be lost. And this mind realizing emptiness is an incredible force, an incredible power. It burns the wood of all afflictions in the continuum of a bodhisattva like Samantabhadra. Even though their body is still in samsara, their mind is not under the control of the afflictions because of the mind realizing emptiness. Their powerful mind of wisdom—this wisdom mind that realizes emptiness—is able to burn the wood of afflictions, so the faults of samsara don’t affect them. They don’t affect bodhisattvas.

We are reborn through the power of our afflictions, therefore afflictions of samsara actually harm us. We experience all the different disadvantages of samsara: being uncontrolled, being reborn, experiencing suffering all the time. Without wanting to, we accumulate a lot of negative karma, so these are the disadvantages of samsara. But a bodhisattva is free from all this because of the wisdom fire of emptiness. And the stronger their wisdom of emptiness, the stronger their love and compassion becomes. They are not reduced by their realization of emptiness. Instead, with their afflictions being reduced, being weakened, being overcome, then in its place, there is more love, more compassion, more forbearance, the awakening mind. All these positive qualities are not reduced, but they become stronger because of their mind realizing emptiness. In the place of the afflictions, now these incredible qualities are generated, and they become stronger. Therefore, they still remain moistened by compassion as it says in this verse. It increases their compassion.

How buddhas benefit sentient beings

Verses 91 and 92:

Those under the power of compassion

Display acts of departing, birth and merriment,

Renouncing kingdom, engaging in ascetic penance,

Great awakening and defeating the maras,Turning the wheel of Dharma,

Entering the realm of all gods,

And likewise display the act of going

Beyond the bounds of sorrow.

This talks about Buddha himself. Everything he does is all for the benefit of sentient beings. This is describing the twelve enlightened activities of a Buddha: coming down from Tushita, being born in the mother’s womb, enjoying the life of a king, leaving the kingdom behind, and engaging in ascetic practices and so forth. This verse is describing the twelve enlightened deeds of a wheel-turning Buddha.

Then verse 93:

In guises of Brahma, Indra and Vishnu,

And that of fierce Rudra forms,

They perform the compassionate dance

With acts bringing peace to the beings.

The Buddha may manifest, may emanate, as Brahma, Indra and so forth and bring benefit to others. It’s this compassionate dance. When we say Brahma, Indra and Vishnu, does this mean that these celestial beings are actually emanations of the Buddha? Or does the Buddha manifest somewhere else? Brahma, Indra and Vishnu are ordinary beings, samsaric beings. When it says the Buddha manifests as Brahma, Indra and Vishnu, that needs to be analysed. These emanations of Brahma and so forth benefit limitless sentient beings. The Buddha has this power, has this ability, because of the great prayers the Buddha previously made and the virtue he has accumulated.

It’s important to understand that if there’s not enough virtue or not enough positive karma that has been accumulated, they won’t be able to engage in these actions. This incredible merit had to be accumulated first. The verses previously talked about working for the benefit of all sentient beings—attaining liberation or Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings—and it said that solitary realizers don’t have the same love and compassion or determination to benefit other sentient beings. So, they reach a lesser kind of awakening because of not having the same determination. This verse says that liberation is the final goal, so with regard to this particular view, the next verse is given.

Different paths to awakening

Verse 94:

For those disheartened on existence’s road,

For their respite the two wisdoms that lead

To the great vehicle had been taught;

They are [however] not ultimate.

This is talking about those who are disheartened by samsara, who are disgusted by samsara, who just want to be free from samsara. If they only aim towards self-liberation, if someone has that strong attitude and wants to become a solitary realizer—someone whose attitude doesn’t include the welfare of all sentient beings—then it is explained that this is the final goal. This is the final goal for their respite. But if we compare the two wisdoms—those on the fundamental vehicle and those on the bodhisattva path—saying that both are final results is not definitive. It needs to be interpreted. Self-liberation and Buddhahood are not both final results. It is not the case that the fundamental vehicle is a final vehicle. Because those who attain self-liberation also enter the bodhisattva path and will attain Buddhahood, but there are some who first become self-liberated and then enter the universal vehicle. That’s why it is taught that it is appropriate for those beings who are not ready now to enter the universal vehicle path. For those beings, the Buddha taught that there is another vehicle that he described as an ultimate vehicle.

Verses 95-96::

So long not exhorted by the Buddhas,

So long the disciples will remain

In a bodily state of wisdom

Swoon and intoxicated by absorption.When exhorted then in diverse forms

They will become attached to others’ welfare;

And if they gather stores of merit and wisdom,

They will attain the Buddha’s [full] awakening.

So, this is talking about a hero who has attained the state of self-liberation. Once they have reached that state of liberation then having attained the pacification of all afflictions, of all sufferings, they are absorbed in this meditative equipoise. They are just absorbed in that cessation for many many lifetimes. For many eons, they may remain in that absorption—this concentration that is so deep that they remain focused on their cessation of suffering. Being in that state of wisdom, it is possible to enter the Mahayana path when they become attached to others’ welfare, and if they gather stores of merit and wisdom. Then they will attain the Buddha’s full awakening, but first they remain in this absorption.

So, from that point of view, remaining in that state of self-liberation for a long time seems to be a final vehicle, but it is not. In the end, the Buddha will basically awaken them from this absorption. The Buddha inspires them to arise from concentration, so then they have no body. They don’t have a body when they arise from that concentration, because they have overcome afflictions. But there is no coarse body, and they will need a body to benefit other sentient beings. Therefore, there is something like a mental body that is manifested, and on that basis, they benefit other sentient beings and gather the stores of merit and wisdom. So, this verse is talking about beings who remain in the state of self-liberation totally focused on their sensations for many, many eons, and then when they are inspired by the Buddhas, when they are exhorted by the Buddhas, they emanate this mental body on the basis of which they can accumulate merit and wisdom and work for the benefit of other sentient beings. This kind of body gathers stores of merit and wisdom, and they will attain the Buddha’s full awakening.

Verse 97:

Because the propensities for two [obscurations] exist,

These propensities are referred to as seeds [of existence],

From the meeting of the seeds with conditions

The shoot of cyclic existence is produced.

The appearance of inherent existence, that dualistic appearance, comes from the obscurations. These imprints for the dualistic appearance—for the appearance of inherent existence—are defiled imprints, so this gives rise to a body. We take a coarse body as a result of our afflictions, but these beings who’ve attained self-liberation and now enter the Mahayana path also take birth in a sense, but it’s not the same kind of taking birth. It’s a controlled process where the cognitive obscurations give rise to this mental body that also needs to be left behind in the end. It’s an imprint. It’s something that needs to be eventually overcome. Therefore, this is also not the final goal. That kind of mental body is not a totally pure body. The imprints give rise to this mental body, but because the imprints need to be overcome, then this particular body also needs to be overcome. So, a bodhisattva who has taken on this mental body will eventually leave it behind. They need to overcome that. They overcome the imprints which gave rise to this particular body.

These propensities are referred to as seeds. From the meeting of the seeds with conditions, the shoot of cyclic existence is produced. They’re born in cyclic existence, but in a sense, it’s a controlled birth because it’s not just the seeds. It’s also the wish to benefit other sentient beings. It’s this aspiration to benefit others and also undefiled karma. So, the combination of undefiled karma, the wish to benefit sentient beings, and the seeds—these propensities or imprints—give rise to this special kind of body. When we say undefiled karma, it’s like having the power to control this process.

Verse 98:

[The paths] revealed by the saviors of the world,

Which follow the pattern of beings’ mentalities,

Differ variously among the diverse people

Due to the diverse methods [employed by the Buddhas].

It’s not like the Buddha just teaches, thinking, “I think that’s best.” This is not what the Buddha thinks. The Buddha doesn’t teach considering this Dharma to be the best Dharma. It’s always in relation to what beings need. It’s in accordance to their mentalities, their needs, their attitudes, and so forth. For instance, we can’t say a certain medicine is the best kind of medicine because it depends on a person’s disease. There are certain medicines that don’t help a person, because they don’t have the kind of sickness that these medicines can cure. If someone has a cold, you need to give them medicine for the cold, but there are different types of colds. There are different kinds of flus. Determining which medicine is best is all in relation to the disease. Likewise, the Buddha teaches in accordance with beings’ needs, mentalities, and so forth. That’s why the Buddha teaches in so many different ways. That’s why there are so many different methods. It’s because there are so many different needs that sentient beings have.

Sometimes the Buddha said that there is a self. So, he taught the law of karma, but he also said there is a self. And sometimes he said there is no self. Sometimes he said there are external phenomena, and sometimes he said there are no external phenomena. It always depended on the needs, on the predispositions, on the interests, and so forth of the different disciples, and depending on all these factors, the Buddha then taught what is most appropriate to that person. The Buddha only taught what benefited the person the most given their present situation. That’s the quality of the Buddha: that he taught what is most beneficial to beings.

Verse 99:

[The instructions] differ as the profound and as the vast;

On some occasions [an instruction] is characterized by both;

Though such diverse approaches are taught,

They are [all] equal in being empty and non-dual.

Sometimes a profound teaching is given, a teaching based on wisdom. And sometimes a very vast teaching is given, an explanation on a different method and so forth. Sometimes both are taught, so profound and vast teachings are given. There are so many different approaches, but they are all equal in being empty and non-dual. In the end, the Buddha always taught emptiness, so there is no difference when leading a being to the final goal. Emptiness is always the same. It all comes down to suchness. Everything the Buddha taught is to lead sentient beings to the final suchness. Either directly or indirectly, the Buddha basically always taught to lead sentient beings to understanding emptiness.

Buddhahood is the ultimate goal

Verse 100:

The retention powers and the [bodhisattva] levels,

As well as the perfection of the Buddhas,

The omniscient ones taught these to be

Aspects of the awakening mind.

Self-liberation is not the final goal. The final ultimate goal is Buddhahood. If Buddhahood is the ultimate goal, then the methods that lead there also have to be the ultimate. They also have to be the final methods. They have to be complete in order to lead a bodhisattva to the state of Buddhahood. If the result is excellent, the cause has to be excellent. The methods of the bodhisattva are excellent, and so the vehicle of the bodhisattva is the final vehicle that leads to the final goal of Buddhahood. There are so many different methods. The retention powers and the different bodhisattva levels, the six perfections—all these different teachings are all methods. They’re all different methods that lead to enlightenment. The six clairvoyances, the five special perceptions and so forth, the different powers for mindfulness—all these teachings are methods that lead a bodhisattva to the state of Buddhahood. These are all branches of bodhicitta, of the awakening mind. We need all these other practices as well, but they all support bodhicitta. They’re all part of bodhicitta. They are all branches of the mind of enlightenment, so when we meditate on bodhicitta, we need all these other aspects as well. Then we will be able to reach the state of a Buddha with this complete practice of all these methods. So, the enlightenment of a Buddha is the final state, the ultimate goal.

Buddhas never stop benefiting others

Verse 101:

Those who fulfill other’s welfare in this way

Constantly through their body, speech and mind,

Who advocate the dialectic of emptiness,

There is no dispute at all of being nihilistic.

Some would say that once you become an arhat your mental continuum is cut. In the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika schools, they would have said that once you become an arhat your continuum is cut. You’re severed. The Buddha’s continuum is severed after a Buddha becomes enlightened, and after the Buddha passes away. They say that the mind no longer continues. there’s this view. But here it says that once they become enlightened, they always continue on. They always exist. The mental continuum of a Buddha is not severed. When it says “dialectic,” it means in the sense of a debate; it’s saying they set forth these different discussions. Therefore, this view of nihilism doesn’t arise. Just because they overcome this body, it doesn’t mean that they stop working for the benefit of other sentient beings. So, there is this nihilistic kind of view that the Buddha’s continuum will be severed, but actually, that’s not the case from a Prasangika school point of view.

Verse 102:

Neither in cyclic existence nor in nirvana

The great beings reside;

Therefore the Buddhas taught here

The non-abiding nirvana.

Even though they are not caught in the two extremes of nirvana and samsara, this doesn’t mean that they don’t remain in samsara. They do remain in samsara, but they’re not caught in the extreme of samsara. There’s a difference. What is the extreme of samsara? It means being reborn as caused by karma and afflictions—being reborn uncontrollably in samsara. That’s what it means to be caught in the extreme of samsara: being reborn uncontrollably. For a buddha or a bodhisattva, they don’t consider samsara to be something that has to be totally left behind. They want to benefit sentient beings, so they remain in samsara, but they’re not caught in the extreme of samsara. They’re not caught in the extreme of just self-liberation. Therefore, Buddhahood means non-abiding nirvana: not abiding in the extreme of cyclic existence nor abiding in the extreme of nirvana. Once attained, self-liberation would be in the extreme, because you remain in that absorption for a long time.

Verse 103:

The single taste of compassion is merit;

The taste of emptiness is most excellent;

Those who drink [the elixir of emptiness] to realize

Self and other’s welfare are conqueror’s children.

Working for the benefit of sentient beings, a buddha’s continuum is not severed. When we talk about “conqueror’s children,” we’re referring to bodhisattvas. That’s another word for bodhisattva. Before you become a Buddha, you have to be a bodhisattva. So, those who drink the elixir of emptiness to realize self-enlightenment and for the welfare of others are conqueror’s children. They practice both emptiness and compassion.

Verse 104:

Bow to them with your entire being;

They are always worthy of honor in the three worlds;

These guides of the world reside

As representatives of the Buddhas.

Because they work towards Buddhahood, they are similar to buddhas. Therefore, we have to bow to them with our entire being. If we offer something to a buddha or to a bodhisattva, we’re actually offering it to all sentient beings. So, we should offer everything to them, because we benefit indirectly all sentient beings. The bodhisattvas are always worthy of honor because they’re like representatives of the Buddhas. Therefore, we should honor Bodhisattvas. This is mainly referring to the bodhisattvas as the representatives of the buddhas.

The jewel of the awakening mind

Verse 105:

This awakening mind is stated

To be the highest [ideal] in the great vehicle;

So with an absorbed [determined] effort

Generate this awakening mind.

A bodhisattva’s awakening mind is the heart, the life force, of the universal vehicle. With an absorbed, determined effort, we should meditate on this awakening mind. We should reflect on this again and again in order to generate it in our own continuum.

Verse 106:

To accomplish self and others’ welfare

No other means exist in the world;

Apart from the awakening mind

To date the Buddhas saw no other means.

This is similar to what it says in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life by Shantideva. So, there’s no other method than the awakening mind. Even the Buddhas so far have never seen any other means than the awakening mind. There’s no other method to attaining enlightenment. There are no other methods to dedicate ourselves for the welfare of sentient beings. There’s nothing greater than bodhicitta, so we definitely have to generate that.

Verse 107:

The merit that is obtained

From mere generation of awakening mind,

If it were to assume a form

It will fill more than the expanse of space.

The merit that comes from the awakening mind has no limit. It’s so vast.

Verse 108:

A person who for an instant

Meditates on the awakening mind,

The heap of merit obtained [from this],

Not even the conquerors can measure.

In the same way that there’s no limit to space, a person who for an instant meditates on the awakening mind creates a heap of merit that not even the conquerors can measure. It’s just one second; it’s just for an instant. But the merit is so limitless. Not even a conqueror can actually measure it. How amazing! There’s no way that the Buddha can express verbally what this merit is.

Verse 109:

A precious mind that is free of afflictions,

This is the most unique and excellent jewel;

It can be neither harmed nor stolen by

Such robbers as the mara of afflictions.

There’s no sense of self-centeredness. The thought of “I, I, I” doesn’t arise. A precious mind is free from these afflictions, and that’s like a jewel. For instance, in the third chapter of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, it says that there’s nothing greater than the suffering of sentient beings—of poverty and so forth. So, bodhicitta is like the greatest kind of jewel that helps us in our difficult states. Bodhichitta is this incredible jewel. It’s the final jewel. It’s the ultimate jewel. Even external jewels, material jewels, can be destroyed. They can be stolen. They can be lost. They can basically decay. They can deteriorate. But bodhichitta cannot be destroyed. No one can take it away from us. It’s free of the afflictions, so it cannot be harmed or stolen by robbers, such as Mara or the evil forces of afflictions. Bodhichitta can destroy other things. It can destroy the afflictions and so forth. But the afflictions cannot destroy bodhichitta. It’s like when you have gold and you have dirt. The afflictions are like dirt and gold is like bodhichitta. Gold is always more magnificent than the dirt. It’s not like the dirt outshines the gold.

May I be unswerving

Verse 110:

Just as aspirations of the Buddhas

And the bodhisattvas are unswerving,

Likewise those who immerse themselves in

Awakening mind must hold firm their thought.

This is similar to our aspiration prayer: “As long as space remains, as long as sentient beings remain, may I also remain to remove the misery of sentient beings.” So, just as aspirations of the buddhas and the bodhisattvas are unswerving and so forth, may I, too, always work for the benefit of sentient beings. This is saying to immerse ourselves in the awakening mind and hold this firm. It means remaining in samsara and continuing to work for the sentient beings. That’s the prayer here: “May I be unswerving.” Just like with the aspiration prayer, “May I always remain, just as space remains, and so forth.”

Verse 111:

Even with wonder you should strive

As explained here [in the preceding lines];

Thereafter you will yourself realize

Samantabhadra’s [great enlightened] deed.

Now Nagarjuna is talking to us like wisdom disciples. He’s saying, “You should strive as I’ve explained in the previous verses. If you don’t do that, then that’s silly because thereafter you will realize the great enlightened deeds of Samantabhadra.” So, in dependence on the practice of a bodhisattva, your mind will expand. It will become more vast, and you will be able to realize the same state as Samantabhadra. You will be able to gradually reach this incredible state.

Verse 112:

By praising the awakening mind hailed by the excellent conquerors,

The incomparable merits I have obtained today from this act,

May through this all sentient beings submerged in the waves of existence ocean

Travel on the path trodden by the leader of the bipeds.

Therefore, may all sentient beings—who are now in samsara, who are submerged in cyclic existence—travel on the path of the great master Arya Nagarjuna. This concludes Commentary on the Awakening Mind composed by the great master Arya Nagarjuna. It was translated and edited by the Indian abbot Gunakara and the translator Rapshi Shenyen, and was later revised by the Indian abbot Kanakavarma and the Tibetan translator Patsap Nyima Drak.

Questions & Answers

Audience: When anger arises towards another, thinking they are wrong and I’m right, how can I more quickly recall the true aspect of non-duality and fully appreciate the felt peace of that recognition?

Yangten Rinpoche: We do think like this when we are really angry with another person: “This person is wrong, and I’m right.” We have this attitude. At that time, first we need to think that maybe they have made a mistake. But that’s not the main point. We need to reflect: “How does anger benefit me? How does it harm me?” We really need to reflect on that. If we consider what it is that really harms or benefits us, then we realize that when we get really angry it’s difficult to think of the path right away. It’s difficult to reflect on emptiness, on the awakening mind. When there’s strong anger, we can’t think of emptiness right away. It’s very difficult to switch. So, unless we’re very familiar with emptiness, we won’t be able to deal with it. Therefore, when we’re really, really angry, we should think, “I’m angry. How does it benefit me? Does it really benefit me to get angry?” That thought should arise.

When we have a lot of anger, it will not benefit us. It will actually really harm us. Let’s leave aside whether or not it benefits us for a moment. First, will it not harm us? This attitude should arise. If we have this thought then the anger will slowly weaken, and we can start thinking about the path. We can think about emptiness, about forbearance, patience and so forth. But when anger is really strong, this is not going to happen. For instance, when we plant a flower, we have to undergo certain steps. We can’t go from planting a seed to right away having a flower. Similarly, when we’re angry, we can’t right away meditate on emptiness. When we plant a seed, we have to wait for a while. Likewise, we can’t meditate on the path right away when we’re really, really angry or meditate on emptiness. It’s not going to happen. It takes time. That’s not in accordance with reality, I believe.

When we’re really angry with another person, our focus is the other person we’re angry with, so we have to let go of that focus. We need to think of something else—maybe a person we really like. Think about them, because as long as we’re focused on the person we’re angry at then we’ll be angry. We have to let go of our object and then the anger will be reduced. Another thing we can do is to become aware of our anger. We can reflect that “This will harm me. This will make me unhappy.” Reflect on that; ask, “How does it benefit me if I get angry?” We can really remember that in that moment, and in that way, the anger can be weakened. If we think about it, anger doesn’t serve any purpose. Not only does it not benefit us, it only harms us. It really just harms us.

Audience: When we have a lot of anger in our mind, but we don’t harm the other person then what does it harm? How does it harm the other person?

Yangten Rinpoche: The anger doesn’t harm the other person, but our actions out of anger do. For instance, I might start beating this person or hitting this person with a stick out of anger. So, does it really harm the other person? No, it doesn’t really harm the other. If we act upon this anger, if we harm the other person, who is this really harming? We need to reflect on that. In short, that which really harms us is anger. Anger is really what harms us the most. If you think about it, it doesn’t solve the problem, but it just harms us.

The best thing for us is compassion. Even if we beat someone up, there’s no guarantee that we harm the other person. There’s no guarantee if we beat them up that it harms them. But being angry doesn’t benefit us in any way because our mind is not peaceful. So, we cannot really act or respond in a good way. Therefore, the best thing we can do is to actually show this other person that their way of doing things is not okay. We can show them that it’s much better if you remain calm. Then we can also guide the other person and help them to overcome this anger.

Audience: Are the Four Noble Truths essentially true? Is the emptiness of emptiness essentially true?

Yangten Rinpoche: I guess “essentially true” here means does it exist by way of its own nature? All phenomena from form all the way up to the enlightened mind don’t exist inherently. Nothing exists inherently. All phenomena lack inherent existence. Whatever exists lacks inherent existence. It doesn’t exist by way of its own nature. This is true for all phenomena.

Audience: Rinpoche, how can it be that the bliss of working for sentient beings or bodhicitta is greater than the bliss of concentration?

Yangten Rinpoche: The bliss of absorption or the bliss of concentration only benefits us. It benefits us when we have this concentration. We have this experience, this bliss. But bodhicitta benefits all sentient beings. There’s a mind that is focused on all sentient beings: “What can I do to benefit all sentient beings? How can I benefit them?” When we think about other sentient beings all the time, it’s a very vast and extensive mind. There’s no more extensive attitude. There’s nothing more positive, more magnificent. Therefore, it’s so much more precious. But when we talk about the bliss of concentration, there are so many different kinds of happiness or bliss. We have the first concentration of the former, the second concentration of the former, and so forth. There are these forms of bliss that come along with them. There’s this state of absence of any disruptive thoughts, so that’s the kind of bliss that is experienced. Or there’s the liberation that our heart experiences, for instance. So, this absorption in the cessation of all afflictive obstructions is also very, very blissful.

For instance, when it’s really hot, if we go inside the room and the air conditioner is running, there’s like this physical bliss. This is just an example—an analogy. Those who attained liberation, because they’re free now from the afflictive obstructions, are just absorbed in the state of cessation. There’s some great bliss apparently because of having overcome these afflictions. The experience you have as a result of the first absorption of the form realm is said to be incredible bliss and joy. Say, for example, that we win the lottery, and we make a lot of money. There’s also a great joy. There’s a lot of happiness. But the happiness or the bliss of this concentration is much greater than that. But we need to let go of this focus on bliss. We need to let go of this and instead focus on all sentient beings. There’s nothing greater than this inner strength that is focused on the welfare of all sentient beings. So, it’s important to be able to let go of any kind of bliss and happiness and instead focus on sentient beings. That is really amazing. This dedication for sentient beings arises as a result of the awakening mind.

Audience: The warm-heartedness that His Holiness the Dalai Lama talks about, is that the same as bodhicitta?

Yangten Rinpoche: Just warm-heartedness is not the same as bodhicitta. Just wanting to benefit other sentient beings is also not bodhicitta. That is incredible. It’s amazing to have warm-heartedness. It’s important. But that’s not bodhicitta yet. We need bodhicitta that is associated with true aspirations. We need compassion that focuses on sentient beings, and wisdom that focuses on enlightenment. So, this is an attitude of not being able to bear the suffering of sentient beings, and based on the wish to help sentient beings to overcome suffering, to need to do something. I need to help sentient beings. It’s this altruistic attitude. Right now I cannot do this. I cannot remove the suffering of sentient beings. Only a Buddha can actually help sentient beings to overcome suffering.

So, in order to benefit sentient beings, to lead sentient beings to Buddhahood, for that reason I aspire to become a Buddha. This thought—“I want to become a buddha for the benefit of all sentient beings. May I become a buddha. May I remove the suffering of all sentient beings. May I lead sentient beings to happiness. May I lead all sentient beings to liberation and Buddhahood”—that is bodhicitta. For that goal, may I become a Buddha. This sincere aspiration to become a Buddha for the benefit of all sentient beings, that’s bodhichitta. And bodhichitta needs a lot of qualities to come together. We need to generate bodhicitta, but we need warmheartedness first in order to generate the mind of enlightenment.

Audience: What is the relationship between bodhichitta and rigpa and Dzogchen?

Yangten Rinpoche: I’m not sure they’re directly related, but we meditate on Dzogchen conjoined with bodhichitta. We meditate on Dzogchen based on bodhichitta. I don’t think you can meditate on Dzogchen without conjoining it with bodhichitta. It doesn’t become a practice of the universal vehicle if it’s not conjoined with bodhichitta. So, on the basis of bodhichitta, conjoined with bodhichitta, we meditate on Dzogchen—or a practitioner practices Dzogchen. It’s difficult to explain this in a few words. This is just a rough explanation to give you a sense of what I’m talking about. There’s a difference between mind and rigpa. With regard to all phenomena, everything is pervaded by rigpa—by this clarity and knowing. So here, rigpa is referring to awareness in the sense of not being affected by concepts, not being defiled by conceptualization. There’s just this purity—this pure awareness or rigpa. There’s this aspect of clarity and knowing without being affected by conceptualization. In order to actualize that, we meditate. To generate this pure awareness of rigpa, we meditate. That’s a different type of meditation.

There are so many different meditations, such as meditation on concentration, on special insight. There’s also meditating on many different aspects of phenomena: meditating on ugliness as an antidote to attachment, meditating on all the different great elements that we find as an antidote to arrogance. There are so many different meditations that help certain afflictions. Dependent arising is also an antidote to arrogance, so we might meditate on dependent arising. There are many different antidotes to the different afflictions we have. There are said to be 84,000, so that means many afflictions. The Buddha taught many different methods to reduce these different afflictions. Therefore, there are many different techniques. We need to pay attention to that and understand that there are so many methods.

Audience: Thank you, Rinpoche. I was wondering what the difference is between the alaya-vijnana and the clear light mind.

Yangten Rinpoche: When we say clear light mind, we refer to the clear light as the spiritual light. That’s where you see the difference between all the different spiritual lights—the clear light and black light. Clear light mind is explained in the tantric texts. This text—A Commentary on the Awakening Mind—is connected to the tantric text, but it’s mainly a sutric text. So, this clear light mind is sometimes described as foundational consciousness or alaya-vijnana. It’s said to be the basis for samsara and the basis for buddhahood. But when we talked about foundational consciousness early on, or alaya-vijnana as it was described earlier, that was the Cittamatra view. In the Cittamatra school, the alaya-vijnana or the foundational consciousness is something else. This foundational consciousness has many different qualities or different attributes that they describe. It is not virtuous; it is not non-virtuous. It’s like the storehouse of the imprints. It has the five omnipresent mental factors and its nature has many different characteristics. This is the view of the Cittamatra school. They talk about a foundational consciousness. That is very different from the clear light mind as it is described in tantra.

Audience: Rinpoche, I’ve heard that the precept body is an imperceptible form, and I’m wondering if you could explain and expand on how the precept body acts as a form.

Yangten Rinpoche: The Vaibhasika and Prangika schools say the precepts or the vows are physical non-perceptible forms. So, what does it mean? Vows are mainly refraining from certain actions of body and speech. You refrain from certain verbal and physical actions. So, this is mainly physical actions they are refraining from. That’s what the vow is. Therefore, these vows are basically physical. They’re in relation to the physical aspects—physical verbal actions and actions of the body. When you refrain from these certain actions then that also has to be physical. If that which you refrain from is physical, then the vow or that refrain has to also be physical.

Actually, we talk about two types of forms here, two types of physical objects: perceptible and non-perceptible. When you have the thought “I will not engage in these actions,” that gives rise to certain actions of body and speech as a result of wanting to refrain from those. This can be perceived. But then based on that determination to not engage in certain actions of body and speech—to refrain from the seven particular physical actions—when you do refrain, there’s also a very subtle form, an internal form, that is created that is physical. Since that which is being refrained from is physical, the precept has to also be physical. For instance, say you want to stop water. Water is physical, so to stop water you need some other physical entity like a wall that can stop the water. Both need to be physical. Likewise here, when you have a very strong wish to refrain from certain actions of body and speech, then that refraining is therefore a form. That’s what the Vaibhasika school says.

Audience: What about the bodhisattva vow: is that a form? What does the Prasangika school say?

Yangten Rinpoche: I’m not sure that they say that it’s a form of refraining. I’m not sure. It’s a non-perceptive kind of form in the Prasangika school. So, they probably also say that it’s form in the Prasangika school. What the Vaibhasika school says is similar to what the Prasangika school says.

Audience: I was just wondering if you could clarify more about the mental absorption in bodhicitta. Is there a middle way? Can we cultivate the bliss of absorption for the benefit of all sentient beings—like these jhanic states that lead to Brahma realms—so that our Brahmas have a quality of immeasurable loving kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity for the benefit of all sentient beings?

Yangten Rinpoche: When it comes to these different concentrations of the first formless realm and so forth, we need to meditate on them to generate bodhicitta. We don’t generate them only to be reborn in the higher realms, but we can meditate on them to deepen our bodhicitta and so forth. Once we have these concentrations then our virtue will become stronger; our virtue will deepen. For instance, if we have the concentration of the form realm, it will benefit in understanding emptiness; it will benefit us when we meditate on bodhicitta and so forth. But it’s not in order to be reborn in some higher states, but just the concentration itself. We’re not saying it’s something we need to overcome, but if we are only attached to these concentrations, if we consider these concentrations to be the goal, then that’s a problem. If we utilize them to meditate on compassion and so forth, that’s acceptable. That’s beneficial.

Audience: Rinpoche, how does monasticism support bodhicitta?

Yangten Rinpoche: When we say bodhicitta or the awakening mind, it arises mainly by meditating on compassion: reflecting on the suffering of other sentient beings, not being able to bear the suffering of other sentient beings. On that basis, we generate compassion. So, first we need to reflect on our own situation, our own suffering, and generate the wish to be free from suffering. We have to first generate renunciation. Without being able to understand our own suffering and wanting to overcome it, we can’t wish that for other sentient beings. When we generate renunciation and then take the vows of a monk or a nun, then it’s more beneficial. It strengthens this in the sense that our afflictions come from our mind. So, before we can overcome the afflictions, before we can reduce them, we have to refrain from negative actions of body and speech.

First we have to overcome the coarser afflictions that give rise to these actions of body and speech. It would be ridiculous to say, “I’m reducing my afflictions, but I’m still engaging in negative actions of body and speech.” Actually, our physical and verbal actions come from the mind. It’s easier to refrain from physical and verbal actions than it is to refrain from having afflictions in the first place. So, if I were to say, “I will only engage in overcoming the afflictions, but I won’t overcome my negative actions,” then that’s not appropriate. It’s important to refrain from certain actions. Once we can control our speech and our body, then we need to control the more subtle afflictions. That’s the kind of sequence here. What really harms others is our physical and verbal actions. Our mental actions don’t really directly harm anyone. In that sense, it’s important to refrain in that way by taking the vows from negative actions of body and speech.

Part 4 in this series:

Yangten Rinpoche