The nature of all phenomena is emptiness

04 Commentary on the Awakening Mind

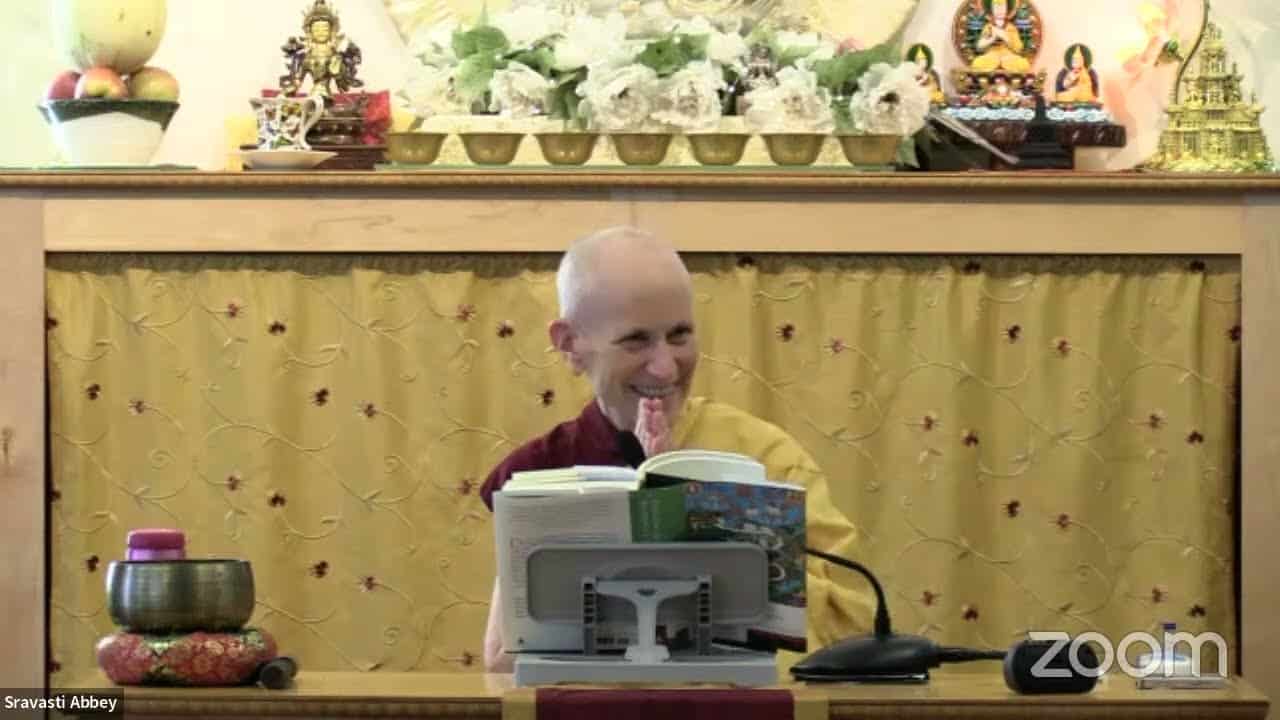

Translated by Geshe Kelsang Wangmo, Yangten Rinpoche explains A Commentary on the Awakening Mind.

If we think about the different reasonings that establish past and future lives then we will realize that having existed since beginningless lifetimes, we will continue to take rebirth in samsara. There are some beings, of course, who remember their past lives. Therefore, in the scriptures, you find so many different reasonings. We can think about these, and then also in society we can meet people who do remember their past lives. When we think about the concept of past and future lives, what does that actually mean? We should really understand what it means. This consciousness has come from a previous life, and it’s taken rebirth in this life and so forth. And we can actually get a good understanding of that if we think about it. This being the case, we’ve existed since beginningless time, and we will continue to be reborn. This is one aspect. And then, what is the root of our samsaric existence? It’s ignorance.

All these problems we have, all our sufferings, come from our own mind. They come from our ignorant mind. This is how it’s explained. From the point of view of just this life, there’s pleasure that comes from the body, and there’s pleasure that comes from the mind. There’s physical suffering and happiness, and there’s mental suffering and happiness. So, when we talk about mental feelings, whether pleasant or unpleasant, they all come from the mind. And when we’re unhappy, for instance, our unhappiness has to do with our mistaken way of thinking, our mistaken reflection on things. All our thoughts have their root cause in attachment.

Attachment is the source of our unhappiness

Attachment is one of the main root afflictions. And if we reflect on this, we realize that all our problems really arise from attachment. Where do our problems come from? Well, first of all, we have this body. Since we’ve taken rebirth in this body then the potential for suffering to arise is there. So, what is the root cause for taking this body? It is ignorance; it’s attachment. It’s these afflictions that give rise to this existence. But if we eliminate the root of ignorance then all the other afflictions and suffering will be eliminated.

And it’s not just that. All impermanent phenomena arise from a cause. This is the nature of impermanent things. Whatever we attach to, we can only achieve it, we can only obtain it, in connection to causes and conditions, or in dependence on causes and conditions. We need to understand, therefore, that there’s a cause for our sufferings. What is the cause of our suffering? It’s ignorance. Ignorance is a mistaken mind; it’s an erroneous mind. Since it’s a mistaken mind, it can be transformed. It can be eliminated. And we cannot rely on this mind because it’s a mistaken mind. But a mistaken mind can be transformed into a non-mistaken mind. This is true for any kind of mistaken mind. So, it can be changed. It can be transformed. It can be overcome. That is just the nature of things; that’s just the nature of this mind.

Repaying the kindness of sentient beings

Therefore, there’s liberation from the afflictions. Liberation is something amazing, but there’s something even greater than liberation, which is to work for the benefit of all sentient beings. While we cycle in cyclic existence, we depend on other sentient beings. This will also be explained in this text later on. Even when we practice the Dharma, when we practice the path, we depend on sentient beings. Even when we attain Buddhahood, we depend on sentient beings. It’s not like once you become a Buddha, you don’t depend on other sentient beings. The Buddha’s enlightened actions are all dependent on other sentient beings. All the activities of a Buddha depend on sentient beings. So, we always have to depend on sentient beings.

Even from the point of view of just this life, from the time we were born we had to depend on our parents. And, of course, our parents depended on other beings, so we depended on those beings, too. Then we went to school, and there were so many other people who helped us while we were in school. We had to depend on teachers and other students, for instance. We needed a school building to go to, and then there had to be people who worked in this school. And then once we graduated from school we needed to find a job. We needed employers and colleagues. We depend on other people when we work. Then when we become older, we need even more support from others. We need hospitals and so forth. So, all our happiness comes from other sentient beings.

It makes sense that if our happiness comes from other sentient beings, we should look after them.Therefore, it’s important to work for the benefit of all sentient beings. Our goal should be to help sentient beings to find lasting happiness, to help sentient beings to overcome suffering, and that is Buddhahood. So,we want to help sentient beings to reach that state, to give them Buddhahood in that way. There’s no greater benefit we can offer to sentient beings. This is the final benefit we can give to sentient beings. There’s no greater benefit that we can offer sentient beings.

Of course, there are other ways in which we can benefit others: we can give them money or a house and so forth, but that’s only temporary. If we give them a house, the house will slowly decay. The house will slowly become old, and it won’t help them in the long term. And anyway, we don’t know whether the person will really find happiness by giving them a house. The best state we can give them is the state of Buddhahood. The best benefit we can give them is to help them to become enlightened. So, in order to do this, we first have to become enlightened ourselves. That’s why we should have the aspiration, the wish, to become enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings. It’s actually a consequence from really reflecting on this. It makes sense that we should work towards becoming enlightened. If we just understand that the root cause of all our problems is a wrong mind then we understand that ignorance can be removed.

And when ignorance is removed then all the other afflictions are removed as well, and there’s no longer any suffering. That’s just the nature of things. It’s the nature of ignorance and so forth that it can be eliminated. And we have the potential to eliminate ignorance. We also have the seeds for great love and compassion. Love and compassion can grow much greater. And that’s just the nature of our mind. Therefore, it’s important to give Buddhahood to other sentient beings. And based on that wish to offer it to others, we should ourselves generate the wish to become enlightened. Unless we’ve reached Buddhahood ourselves, we won’t be able to give it to others. So, that should be our motivation here: to generate the aspiration to become enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings. And there are different methods to attain enlightenment, so we need to know about this. And to know the different methods, we study the commentary of the awakening mind. This should be your motivation for continuing to study this text.

Phenomena are merely labeled

Last time, we made it through verse 43. So, to continue, verse 44 says:

“Entity” is a conceptualization;

Absence of conceptualization is emptiness;

Where conceptualization occurs,

How can there be emptiness?

Here, we talk about entity as inherent existence. This is a computer; this is a cup. This is a vessel to drink tea from. It’s like perceiving it as existing by way of its own character. So, whatever we recognize from the perspective of our mind, it exists. It’s actually just fabricated by the mind. It’s superimposed by the mind. For instance, there are different ways in which we superimpose things. When we say “I,” actually the I is dependent on the five aggregates. But sometimes it seems that the I is the body. Sometimes it seems the I is the mind. Sometimes it seems the I is the feelings. We merely label the I. We label it sometimes on the basis of the body, sometimes on the basis of the mind, sometimes on the basis of feelings. So actually, the self is merely labeled.

We say, “This person is really strong,” or “This person is really thin,” or “This person is really big.” We label this person on the basis of their body. Or we might say, “This person is really happy; this is a happy person.” We label them on the basis of their feelings. Similarly, if it is a person who has a lot of problems then based on the feeling of suffering, we label that this is an unhappy person who has a lot of problems. And we label others as experts, as being well educated; we label some people as having good hearts. All these labels, these designations, depend on certain mental factors. So, they depend on the mental factors of the compositional factor. For example, wisdom or intelligence is one of the 55 mental factors. It’s part of the aggregate of compositional factor. Therefore, on the basis of the compositional factor, we label someone as intelligent and so forth.

Maybe a person’s external appearance is very pleasant, but what about their mind? Externally, they may look really nice, but we distinguish between the external and the internal. And most important is the mind. To determine who this person really is, we check out the mind. So, maybe they look handsome, maybe they’re beautiful from the outside, but actually they’re not a good person, because their mind is mean. They don’t have a good mind. That’s how we label usually.

Similarly, consider someone who can sing really well, like a chanting master. It’s dependent on their voice. And when we say, “This is a dancer,” about someone else then it’s dependent on the body, on their movements. Whatever we label someone—a scholar or an expert, for example—what is the basis for labeling, for designating that? What is the basis for imputing or designating this label? It seems there’s something solid, something concrete, that is that dancer or that expert and so forth. But actually, that’s just an appearance. This is just created by the mind.

So, when it says in this verse that “Entity is a conceptualization; absence of conceptualization is emptiness,” it means that we need to be free from these mistaken conceptualizations, and that is emptiness. In this instance, conceptualization doesn’t just mean attachment and anger and so forth. This is not what this means here in this context. It doesn’t just mean a wrong kind of perception, but it specifically refers to holding on to true existence, perceiving phenomena to exist inherently by way of their own character, by way of existing in and of itself, as if able to sustain themselves. It’s this kind of conceptualization that is meant here.

Emptiness is the absence of this fabrication. Where conceptualization occurs, how can there be emptiness? We superimpose things. When we say, “I don’t exist inherently,” there’s a sense that my aggregates exist inherently. For instance, I can touch my body; I can see my body. So, there’s a sense that my body exists truly, exists inherently. This is how it appears to my mind. When I say, “There’s no self; I don’t exist inherently, but I have a form body; I have a form aggregate” then I’m not able to really understand the final nature, the ultimate nature of phenomena. When I understand emptiness then these mistaken conceptualizations all have to be gone. I come to the conclusion that “I can’t find the self; I can’t find the body.” If I have a sense that the body can be found upon ultimate analysis then I won’t be able to really understand emptiness.

The objects that appear to us, do they exist intrinsically or not? The Buddha, for example: he has attained enlightenment; he’s our teacher, our guide. He’s the one who shows us the path, so he’s very precious and so forth. There’s a sense that the Buddha exists inherently. It appears to our mind as if the Buddha were inherently, objectively existent. But that’s wrong because when we have that sense, we haven’t fully understood emptiness. Therefore, when it comes to emptiness, we need to understand the true meaning. This verse says the absence of conceptualization is emptiness. So, no matter what phenomenon there is, we should understand that it doesn’t exist inherently either. Phenomena cannot be found upon ultimate analysis. They’re not found; they can’t exist inherently. They don’t exist inherently; they don’t exist in and of themselves. We have to have this sense with regard to all phenomena. Once we’re able to do that then we really understand emptiness. We can really grasp emptiness. This is the actual measure of emptiness: understanding that this is true for all phenomena. Therefore, how can there be emptiness unless conceptualization occurs?

There are a lot of explanations when it comes to emptiness. So, when we go through this, we have to explain a lot here. And many of you are probably familiar with emptiness. So here, what is the object of negation? The object of negation is that there’s no existence from the side of the object. And this non-existence, that is the view of emptiness. That is the ultimate view—that phenomena do not exist from their own side. We’re not saying that everything is non-existent. We don’t say all phenomena are the object of negation. That would mean that I don’t exist, that there’s no protector, that you don’t exist, that there’s no path to meditate on, that there’s no bodhichitta, that there’s no Buddha, that there’s no buddhahood. If we were to say all phenomena are the object of negation, then what are we going to meditate on? There’s nothing to practice; there’s nothing left to practice. Therefore, we have to think in a very profound way about this.

Then verse 45 says:

The mind in terms of the perceived and perceiver,

This the Tathagatas have never seen;

Where there is the perceived and perceiver,

There is no enlightenment.

When it says “perceived and perceiver,” maybe this could be interpreted from the point of view of the Cittamatra school: in relation to the same thing, something is the perceiver and the perceived. Like the self-knower, for instance; it could be interpreted to mean this. If something perceives itself then it has to exist truly. Or we could say the perceiver is a mistaken mind perceiving phenomena to exist inherently. It perceives that which is being used to exist inherently, to exist by way of its own character and so forth. So, this verse is saying that perceiving something as inherently existent—grasping a true existence—is something the Tathagatas have never seen. The Tathagatas are free from this kind of mistaken perceiver, since it’s not in accordance with reality. This is the kind of temporary obscurations that a Buddha has eliminated. These obstructions have been eliminated.

When it says, “Where there is perceived and perceiver, there’s no enlightenment” means that whenever there’s a mistaken appearance, whether the mind is mistaken or the object is mistaken, there’s no enlightenment. Enlightenment means a state where everything is purified. So, what is emptiness, actually? What is this emptiness? What is the actual meaning when we say emptiness? We need to immerse our mind into this emptiness as if it was water. We immerse ourselves in the water of emptiness.

Not-finding versus not existing

Verse 46:

Devoid of characteristics and origination,

Devoid of substantive reality and transcending speech,

Space, awakening mind and enlightenment

Possess the characteristics of non-duality.

When we say different objects, for instance, like a pen or other objects, none of those exist inherently. They don’t exist from their own side. There’s nothing concrete to really point at as being its essence. When it says, “Devoid of substantive reality and transcending speech,” what does it really mean? Nothing can be recognized from the side of the object—that’s probably what it means. It doesn’t exist in and of itself. Emptiness cannot be expressed the way it exists actually. It’s like it transcends speech. When we try to explain emptiness on the basis of our understanding of the conceptual mind, we can talk about it, but it won’t be the same experience. It’s impossible that speech exactly expresses what emptiness is. We can have a coarse sense of what emptiness is and, on that basis, talk about it. But it’s impossible that we can actually see it as clearly as we would see like a clear fruit on the palm of our hand. In that sense, we cannot see it exactly the way it exists.

Whatever emptiness means to us, it’s like a coarse sense of emptiness that we have that we can talk about indirectly. We can indirectly talk about emptiness. We can never really express it exactly the way it does exist. It’s impossible for speech. And this is not just true for emptiness but for anything that we’ve experienced directly. For instance, if we eat a sweet object, like a candy, how do you explain what sweetness is for someone who has never experienced it? If you want to explain to them that there is something that is sweet, what are you going to tell them? It’s very difficult to describe with your own words what sweetness is, so, in the end, all we can say is, “Eat it and then you’ll know what I’m talking about.”

With emptiness it’s even more difficult. When it comes to emptiness, it’s very difficult to actually put it into words and really explain it. In The Heart Sutra they say it cannot be expressed; it is beyond thought. To really understand when we talk about emptiness, we can say it just appears. For instance, with the person, it just appears. From the top of our head all the way to the soles of our feet, there’s nothing from this side of the aggregates. It seems that there’s something really from the side of the aggregates. There seems to be something there—something existing by way of its own character, something that is self-sustained. It seems like somewhere within this body there is this self, but actually, that cannot be found. So, this non-existence is selflessness, but is this self totally non-existent?

Really, we should have to say there’s no self. There’s nothing to really point at, so we have to say it’s not there. But there’s a difference between analyzing and not finding it and it not being there. There’s a difference between not being able to find it and it not being there. We analyzed it and couldn’t find it, but there’s a difference between saying I didn’t find it with ultimate analysis and saying it’s non-existent. There’s a difference here. If we apply ultimate analysis we can’t find it, but we’re not finding its non-existence. There’s a difference between not finding it versus finding its non-existence.

Examples of dependently existing

For instance, our eye consciousness cannot perceive sound, and our ear consciousness cannot hear color and shapes. But does our eye consciousness perceive the non-existence of sound? No, that’s not the case. If the eye consciousness were to realize the non-existence of sound then sound wouldn’t exist. Here, we’re not saying that we find the non-existence of something. We just don’t find phenomena. And this is not just true for the eye; this is true for all phenomena. None of the phenomena we see can be found. To give an example of a computer, when we engage in ultimate analysis and look for it among its basis of imputation, what is the computer? What makes it a computer? If it has certain characteristics then it’s a computer. There are so many different computers nowadays, so we can’t say it has to have a certain shape or that it has to have a keyboard. We can’t even say it’s something we can use the internet with because then even our phone becomes the computer. But when we say “computer,” what does it mean? It seems like the computer has a brain. It sounds like there’s a mechanical brain inside it. So, what is the computer? Is it this brain inside it? That itself doesn’t really perform the function of a computer; you need more than that. We need to be able to type documents, to be able to enter them into the computer, to upload things, to download things. Just this internal aspect, this internal brain, is not sufficient.

And there are different levels to that. When it was first made, for instance, how many technical things do you need to add when you put the computer together? When does it become a computer? What is it exactly that is needed? In short, what is it exactly that makes a computer? When we analyze, the more we look for the computer, the clearer it becomes that it cannot be found. That’s the sign that shows that it doesn’t exist truly, because if it existed truly, the moment we look for it, it should become clear what a computer is exactly. So, what does it really mean to be a computer?

Or what about the human brain? Is that a computer? Is the human brain a computer? A lot of functions that a computer performs a human brain performs as well. And, of course, a lot of things that a computer can’t do, a human brain can do. Our brain can do so because humans made the computer. It’s not like the computer made humans; it’s the other way around. That means we have a lot of things we can do that a computer can’t do. Therefore, if we analyze, it’s very difficult to really determine what is a computer or not. Take the situation in this world, for instance: we can’t really know all the things because we don’t have clairvoyance. If we had clairvoyance, if we were able to know everything, then we wouldn’t need a computer. If a person knows everything, if they can do everything, if they have a super brain, they wouldn’t need a computer. So, in dependence on that person,that is really a computer.

It’s helpful to give a lot of examples because it becomes clearer. So, sometimes there is wind. When the walls of this building stop the wind it actually benefits us. The wind doesn’t come through the walls. When we close the windows and the doors, we are protected from the wind. Also, when we close everything and lock the doors and windows then no thieves can come. But if there was someone who could walk through walls then we couldn’t stop this person. There would be nothing to stop them. Therefore, if they can walk through walls, then in relation to that person, this is not a lock. A lock on the window doesn’t become a lock in relation to a person who can walk through walls. They are not stopped by such a wall, so in relation to that person, we don’t say that this is a lock.

Consider Wi-Fi: it can actually come through the wall. The wall is not like an object of obstruction for the Wi-Fi. There is nothing that obstructs it, so in relation to the Wi-Fi, it is not obstructed. Being obstructed or not is dependent on something else. This is also true for other things. This is also true regarding the computer: for the person who uses this object as a computer, it becomes a computer. So, with a person who needs to use the computer, if there is a certain job that this person is doing, then in dependence on that person we can say it’s a computer, isn’t it? If this person doesn’t need this computer, if it has no connection to that person then it’s not a computer for that person. In that sense, all phenomena depend on other things in relation to which they are something.

When we analyze phenomena there is nothing that we can really point at, saying that it doesn’t exist in relation to something else. Here at Sravasti Abbey, I know you are all vegetarian, but I’m going to use the example of meat. When I say “meat,” what is it actually what are we calling “meat”? Is it all the body of an animal? Is every body of an animal meat? Our body is meat actually. If we say that it’s meat, we don’t have a problem with it. Everyone will say, “Of course.” But these insects that look like a leaf from a tree, for instance, or like a piece of wood, are they meat? These insects that look like little sticks: are they meat?

When we analyze, it’s difficult to determine what is and is not meat. There are so many different types of meat. There are so many different animals. There are so many different fish in the ocean and so many different types of animals. There are animals that look like flowers and some that look like mucus and some that look like grass. There are so many different kinds, so are they meat or not? And some animals don’t have blood, for instance. There is only like a white substance coming out of their body, so is it blood or not? Is that type of animal meat or not? And what is blood anyway? So again, it’s all in dependence on other things. It’s very difficult to determine exactly what something is and what it’s not. When we analyze it, we don’t really find anything from the side of the object.

Space, the awakening mind and enlightenment possess the characteristics of nonduality. Here, space is what we usually think of when we think “space,” and then the awakening mind is the mind of bodhicitta in the continuum of a bodhisattva. And then enlightenment is the resultant mind. So, when we talk about the basis, the path and the result, none of those can be found. When we say “the basis,” the objects that we see around us are the basis. So, here it uses space as an example, but everything else around us, all these sense objects that we can see around us, are all a basis. On that basis, we then meditate on the path, and in dependence on that, we attain enlightenment. None of those can be found. Whether it’s samsara or nirvana, none of them can be found. There’s no difference in terms of these two not being findable. So actually, they are nondual.

Explaining non-duality

Here, nonduality means that when it comes to good and bad, they are really not separate. Virtue and non virtue are also non-dual. They are non-dual in the sense that they are not really different from the point of view of not being able to find them. But what does that really mean? We don’t say that negative karma is positive karma, so when we say a negative path or a harmful path, it doesn’t mean it’s a beneficial path. If a harmful path were a beneficial path we would have already become enlightened. And saying negative karma is also positive karma doesn’t make sense. So, no one is saying that, but here, from the point of view of the basis, path and result, there’s no difference between them.

This is a little difficult to understand, but it’s definitely very beneficial. So, for example, from the point of view of emptiness, samsara and nirvana are non-dual. And consider bodhicitta, the wish to become enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings: when we have this attitude that perceives all sentient beings equally, when we have this conventional mind with regard to the path that is practiced and all sentient beings, then it’s all equal in that sense that it doesn’t matter who this person is or whether this person is poor or has a high status. Our view with regard to sentient beings is totally impartial. We have the same attitude regardless. So, this mind becomes very fast. It has a similar attitude when it comes to all sentient beings—like having this view that they are all equal. So, whether someone pays us a lot of compliments or not or whether someone criticizes us, it doesn’t matter.

Enlightenment is what we aspire to, so we have respect for the Buddha, but it’s because the Buddha is precious, not because of attachment and so forth. For a practitioner, the Buddha is precious because of his incredible qualities but not due to attachment. Buddhas are not the same as beings of samsara. A Buddha has attained Buddhahood, so they are not the same. But actually, both are extremely precious because we need to depend on both of them—the samsaric being and the Buddha. They are both extremely kind to us, and they are both the same in not wanting to suffer and wanting to be happy. One of them has attachment while the other is free from attachment, but just because a person is poor we don’t need to have aversion towards them. Even if they make a mistake, there is no reason to become angry with them. Rather, we need to help them so that in the end they can become a Buddha. Therefore, if our mind is impartial then we see all sentient beings as equal. So, from a conventional point of view, we are saying that samsara and nirvana are equal and that all sentient beings are equal.

Enlightenment is very precious, but it doesn’t exist inherently. It cannot be found using ultimate analysis. So, the Buddha’s mind, the Buddha’s consciousness, is impermanent. It doesn’t change into something else. There is no coarse impermanence—it’s not like the Buddha loses his qualities. But still, subtle impermanence also applies to a Buddha. Therefore, the Buddha doesn’t exist inherently. Sentient beings don’t exist inherently. And in that way they are equal. Both buddhas and sentient beings lack inherent existence. Likewise, nirvana and samsara are equal in that they lack inherent existence. And nirvana and samsara are not that far from each other in our minds. If there are no afflictions then there is nirvana; if the afflictions are there then there is samsara. It’s really just about having certain obstructions or not having these obstructions. On the basis of that, we say liberation or samsara.

It seems like it’s really far away, like “Samsara is over there, somewhere in Asia, and liberation is somewhere in the West.” It seems like you have to take a plane to be able to get from one to the other, but in reality, it’s not like that. Once the obstructions in our mind are gone then we attain liberation; we attain buddhahood. And if they are there then we are in samsara. It doesn’t matter where you are,whether you are in the states or in china—if you have the afflictions you are in samsara. That’s what it’s saying in verse 46. And when we’re talking about removing the defilements, it’s important to start with the coarser afflictions. We won’t be able to reduce the subtle afflictions right away; that’s impossible. So, we start with the coarser ones.

Attachment doesn’t benefit us

In our mind we have strong attachment, so we have the defilement of attachment. And especially we have attachment towards our selves. This kind of attachment binds us to the self. This has to do with our mind; it only has to do with our attitude. It’s not like something else that binds us. It’s not like that they can protect us; it’s only our mind. Actually, this binding doesn’t help us; it seems to benefit us, but actually, our mind being so attached to the I means we can’t let go of this attachment. It doesn’t benefit us at all. Our mind is just holding on, and in reality, it doesn’t make sense. With all it’s holding onto, what benefits us? What is it that benefits us? Our right thoughts, our correct thoughts that are in accordance with reality, are what really help us. If we have a mind that’s in accordance with reality and we act on the basis of that mind, that’s what really benefits us. This attachment doesn’t benefit us. If we have a mind thinking, “I’m so precious,” and we only consider ourselves to be so precious when we see our good qualities and never think of negative qualities then no one is allowed to be angry. So, we have a sense that we’re being humiliated by this other person, but that’s just because of attachment.

For instance, take this cup: if I’m really attached to this cup then if I were in my bed right now I would be worried about this cup the whole time. I’m thinking, “Oh, this cup—what is happening to this cup?” I’m just thinking about this cup. Will this protect this cup? No, it won’t protect the cup. If I really want to protect this cup I put it in a special place, maybe in some iron cabinet. And I lock the cabinet, or I will appoint someone to protect my cup. I give someone some money every month so that they will look after my cup. Then you can really protect the cup. So, what really protects the cup is not the attachment. It requires you to actively do something; we have to really engage in some kind of protective actions. Just having attachment doesn’t protect the cup. And having attachment actually gives us just a hard time, too. Not only does it not protect the cup, but it just gives us a really hard time.

We’re worried that someone will break it or that someone will steal my cup. I’m always worried about this cup or that I will lose it to someone. So, if I don’t see the cup then I’ll always be worried. If I can’t see the cup then I’m thinking about it; I can’t sleep at night. This is what attachment does. Attachment causes so many problems, so we have to understand the nature of attachment. We have the sense that this cup is really precious, so I have to look after it. That’s not attachment saying that something is precious and I have to look after it, but attachment is this extreme mind.

Why am I saying this? It’s because it’s important to let go of the attachment to the self. If we’re so attached to ourselves—if we always think about I, I, I—how does that help us? How does it benefit us? It can benefit us if we look after our health; that’s what really helps, but there’s nothing more we can do. So then we can relax and we can sleep well without this attachment. We can sleep well, we can eat food well, we can look after our health, we can study, we can respect others, we can have a good relationship with others: that’s what really protects us. That’s what’s important. This is what really benefits the self. But we have to let go of this defiled mind, which is attachment. We can let go of that and then we will really be happy. Then we can really experience happiness because our mind will be relaxed. This is similar to liberation. Of course it’s not liberation, but it has a similarity to liberation because we kind of liberate it. There’s a sense of freedom. It’s not actual liberation, it’s not actual freedom, but it’s similar. There’s a similarity in how beneficial this freedom from attachment is. And, of course, how much greater is it when we have actual liberation. It’s so much greater actually. So, in that sense, this is what it says here in the last line of 46. When it says “Possess the characteristics of non-duality,” it’s just a matter of attitude. When it comes to samsara and nirvana, we have to just change our attitude.

Why meditating on emptiness matters

Verse 47:

Those abiding in the heart of enlightenment,

Such as the Buddhas, the great beings,

And all the great compassionate ones

Always understand emptiness to be like space.

Emptiness is like the absence of obstructive contact, so here when we say emptiness, it’s just the absence of something. When we say all phenomena, it’s not like saying that all phenomena don’t exist. Instead, we are saying it’s like space in the sense that it pervades everything. Space and emptiness have some similarities. First of all, space is non-obstructive. It has no limit, so we can go endlessly. There’s no kind of end to space, so even if we had a plane, we could go on endlessly.

Verse 48:

Therefore constantly meditate on this emptiness:

The basis of all phenomena,

Tranquil and illusion-like,

Groundless and destroyer of cyclic existence.

In the Cittamatra school, they say it’s the foundation of consciousness. But this kind of mind doesn’t exist. There’s no truly existent mind, so it’s like an illusion. It doesn’t exist. So, we should meditate on this emptiness, the basis of all phenomena.

Then verse 49:

As “non-origination” and as “emptiness,”

Or as “no-self,” [grasping at] emptiness [as such],

He who meditates on a lesser truth,

This is not [true] meditation.

By understanding emptiness we can overcome existence. We can become liberated from existence, from samsara. The basis of all phenomena—this tranquil and illusion-like, groundless and destroyer of cyclic existence—that’s what destroys cyclic existence. So, what is emptiness? Emptiness refers to all phenomena. It can be applied to all sentient beings, all phenomena. They’re non-originated, so they’re free from all kinds of mistakes. Once you understand emptiness, you’re free from any kind of mistaken appearance and so forth. That’s what we say is emptiness. We’re saying that being free from any kind of conceptualization, having no self grasping at emptiness as such, is emptiness. Here it talks about member as like lesser truth—like he who meditates on a lesser truth. It’s important that we really meditate on the actual truth, so when it says the member as in like inferior, it means an inferior truth. In the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika school they don’t perceive the actual truth; they don’t meditate on the actual truth. They only meditate on a coarse kind of selflessness. And also the Cittamatra school follows a lesser truth. They are only meditating on the lack of external phenomena. Therefore, we have to meditate not on a lesser truth that’s only a part of the truth, only an aspect of the truth. That would be a lesser truth. That would be an inferior truth. That is not true meditation.

Verse 50:

The notions of virtue and non-virtue

Characterized by being [momentary and] disintegrated;

The Buddha has spoken of their emptiness;

Other than this no emptiness is held.

Whether it’s notions of virtue or non virtue, the Buddha has spoken of their emptiness. When we realize emptiness, all these phenomena disappear. None of these phenomena appear to the mind. The mind is non-dual, so once you realize emptiness directly, the conceptual, the conventional, appearances disappear. The generic image doesn’t appear and also subject and object don’t appear. None of these dual appearances arise. When we say conceptualization, like a conceptual mind, for instance, it’s not a direct perceiver. It doesn’t perceive phenomena as it really is. Here we are talking about the direct perception of emptiness, a direct realization of emptiness. When you realize it directly then all appearances will disappear, and then the mind will become non-dual. The mind itself will be free from any kind of dualism; it will be free from any kind of appearance, such as the appearance of inherent existence or conventional truth. This emptiness that appears to the mind is free from all mistaken appearances, so the mind perceives phenomena as it really is. This realization of emptiness is what emptiness is. This is what the Buddha talked about. When it comes to emptiness, no other perception of emptiness other than the direct realization of emptiness perceives emptiness as it really is.

For instance, the way the Svatantrika school and the Cittamatra school describe it is not emptiness. That’s not really emptiness. Other than this, no emptiness is held here. The Svatantrika school doesn’t talk about the lack of inherent existence; they assert inherent existence. And the Cittamatra school perceives the mind to exist truly. The Vaibhasika and the Svatantrika school only refute a coarse kind of self. They only perceive a coarse kind of self; they don’t perceive any kind of ultimate nature with regard to other phenomena. So, in that way, they don’t perceive emptiness.

Total immersion in emptiness

Verse 51:

The abiding of a mind which has no object

Is defined as the characteristic of space;

[So] they accept that meditation in emptiness

Is [in fact] a meditation on space.

The mind that realizes emptiness, that perceives emptiness, is a non-affirming negation that just takes emptiness to mind. When we look at the sky, for instance, we’re not saying the blue sky or the blue space. That’s not what “space” is in this context. It’s got a color. Here, we’re talking about permanent space, which is defined as that which is free from any kind of obstructive contact. It’s just that non-affirming negation; you just negate the obstructive contact. That absence of obstructive contact is what we call space. When this appears to the mind, that’s when this permanent space appears. So, it’s not the case that you can say the object is that or that or something else; there’s no object appearing in the sense of it being this or that or something else. Rather, it’s just the absence of inherent existence. The mind is kind of immersed in that mere absence, so it’s immersed in the sphere of the mere empty. The mind doesn’t think, “Oh, it is empty.” It doesn’t think, “This is emptiness.” It doesn’t have that thought; there’s no sense of “There’s the lack of inherent existence.” It’s just totally immersed in that emptiness.

It’s just the mere absence; nothing else appears. What appears to the mind is just the lack of inherent existence. Just that absence appears; nothing else appears. Only that appears to the mind, but the mind is not thinking, “This non-existence doesn’t exist,” or any other thoughts than that. It’s just like space; it’s like this lack of obstructive contact where just this absence is perceived. So, they accept that meditation on emptiness is in fact the meditation on space, so it’s like meditating on space. This is what the Buddha has said, so this is how we should meditate.

This is how the Buddha described the meditation on emptiness. For instance, say there is a cat in this room. If I were to say, “Please take the cat out,” someone else could say, “Okay,” and come up this stairway and follow this cat. But if I can’t find the cat then there is a sense that there is no cat. So, I’m checking everywhere, but there is no cat. And then, in the end, if I can’t find it and there is a sense of no cat, what happens in that moment when I can’t find the cat?

So, first you need to look for it: “Where is the cat? Oh, it’s not here; it’s not there; it’s not over there. It’s not up here.” In the end, if you don’t find it, there’s this thought, “Oh, there is no cat. There’s just the absence of a cat.” And then you have certainty with regard to that: ”How does this appear? It’s just an absence; just an absence appears to the mind.” So, with the self, I first start looking for the self: “Where is the self?” And there is the absence of just the self, so what does that mean? Actually, what I am realizing now is the lack of inherent existence of the self. “There is really no cat here”: I realize the non-existence of the cat. But here, the way it appears to the mind is similar except we are saying the non-existence of the cat. In the other case, we are saying not the non-existence of the self but the lack of inherent existence of the self. We are not saying the absence of the cat is emptiness; that would be absurd.

Verse 52:

With the lion’s roar of emptiness

All pronouncements are frightened;

Wherever such speakers reside

There emptiness lies in wait.

The lion’s roar is like something that all other animals are scared of, so that’s representing the speech of the Buddha. The Buddha’s roar of emptiness frightens all these philosophers who say that phenomena exists truly. They are frightened. Wherever such speakers reside, their emptiness lies in wait. So, wherever this explanation is given on emptiness, then emptiness lies in wait.

Refuting inherent existence

Then verse 53:

To whom consciousness is momentary,

To them it cannot be permanent;

So if the mind is impermanent,

How could it be consistent with emptiness?

When we ask, “Do phenomena exist inherently or not,” what is the basis? What is consciousness? This is the main kind of doubt we have: is the consciousness the person and does it exist inherently or not? First of all, consciousness is momentary. It changes all the time, so it cannot be permanent. The mind is changing, and because the mind is changing, it’s momentary. This clear and knowing entity, or this clear entity aspect of the mind, sometimes connects to afflictions. Sometimes it’s not connected with afflictions. Then sometimes the mind sleeps, and sometimes the mind doesn’t sleep. So, there are different kinds of situations that the consciousness or the mind changes depending on what it is affected by. It changes, so there is not only coarse change, but there is also very subtle changes from moment-to-moment. If the mind is impermanent, how could it be inconsistent with emptiness? Because it is impermanent it doesn’t exist inherently. It shows that it doesn’t exist inherently because it is impermanent.

In the Cittamatra school, they say that consciousness is impermanent, but they still say that the mind exists truly. But if you say that the mind exists impermanently, that actually shows that it lacks inherent existence. There is no contradiction. You are saying that if it is impermanent then it has to exist truly or it has to exist inherently. That’s what some philosophers say. They talk about the foundational consciousness. They say the foundational consciousness is the self because it is this truly existent entity. But actually, from a Prasangika school point-of-view, that’s contradictory. Therefore, if it’s impermanent, it must lack inherent existence. It’s not inconsistent with emptiness.

Verses 54 and 55:

In brief if the Buddhas uphold

The mind to be impermanent,

How would they not uphold

That it is empty as well.From the very beginning itself

The mind never had any [intrinsic] nature;

It is not being stated here that an entity

Which possesses intrinsic existence [somehow] lacks this.

It never has an intrinsic nature. It’s not like sometimes it exists intrinsically. No, it always lacks intrinsic existence. Either it exists inherently or it doesn’t; both are impossible. Something cannot be both intrinsically existent and non intrinsically existent.

Verse 56:

If one asserts this one abandons

The locus of selfhood in the mind;

It’s not the nature of things

To transcend one’s own intrinsic nature.

When we say the mind is the self, it’s being the self that can be abandoned by reasoning, that can be overcome by reasoning, because the mind lacks inherent existence. But actually, the nature of the mind is to lack inherent existence. Not existing truly is the nature of the mind, so the mind has the nature of lacking true existence. We’re not saying that something is beyond its own nature. We’re not saying that.

Conventional versus ultimate natures

Verse 57:

Just as sweetness is the nature of molasses

And heat the nature of fire,

Likewise we maintain that

The nature of all phenomena is emptiness.

So, for instance, sweetness is the nature of molasses, and therefore we say molasses is sweet. If it was not the nature of molasses to be sweet then it wouldn’t always be sweet. There is no molasses that is not sweet, so that’s the nature of it. This is not contradictory. This is definitely the conventional nature. And the nature of fire is heat. So, we’re not abandoning that. We’re not saying that the nature of fire is not heat. Likewise, we maintain that the nature of all phenomena is emptiness. Molasses is that which is sweet. Is there sour molasses? No, what we call molasses is this kind of blackish-yellowish substance that is sweet. Or if we’re talking about the sugar cane itself, nowadays you break it. So, it’s like a bamboo stick, and then you can actually suck out the kind of liquid inside. That’s “molasses”: this sticky kind of substance that is sweet. And there is no molasses that is not sweet.

Verse 58:

When one speaks of emptiness as the nature [of phenomena],

One in no sense propounds nihilism;

By the same token one does not

Propound eternalism either.

The Prasangika school says nothing exists inherently, and still they describe karma the law of karma. So, if someone were to say that the Prasangika has fallen into the extreme of nihilism then the response is that “I’m free from the two extremes. I’m not saying that the phenomena don’t exist. I’m not saying that there is no nature of things. I’m saying that phenomena don’t exist inherently.” In English it’s very difficult actually; there is a word game here. It’s like we are actually saying that phenomena do not exist by way of their own nature, but they have a nature. So, instead of using the phrase “intrinsically existent,” another way to say it is “Phenomena don’t exist by way of their own nature.”

But they have a nature. I’m not saying that phenomena don’t have a nature. If they didn’t have a nature, I would have fallen into the extreme of nihilism. And then because I’m saying phenomena do not exist by way of their own nature, I’ve not fallen into the extreme of eternalism. A vase, for instance, is not permanent. It doesn’t exist truly, so that’s why I don’t propound eternalism. I’m not saying the law of karma is permanent or the self is permanent. I’m not propounding eternalism. I’m not saying phenomena exist truly and permanently. With regard to the different terminology, according to the Prasangika school, the law of karma works and samsara functions. So, all these works of phenomena exist, but they don’t exist intrinsically.

We talk about someone who cycles in samsara. Everything exists: there is a person who cycles in samsara, and there is samsara. Then, on the other hand, the Heart Sutra says there is no eye, no ear, no nose. When another person hears this they would think the Prasangika school is really weird. They are totally contradictory. Sometimes they say karma exists and so forth, but then the Heart Sutra says there is no eye, no ear, no nose and so forth. But this is not what it means here. We are not saying that nothing exists. We are saying phenomena don’t exist inherently, or they don’t exist by way of their own nature. So, how do they exist? In dependence on karma, we are reborn in samsara and so forth on the conventional level.

Phenomena are like a dream or an illusion

Verse 59:

Starting with ignorance and ending with aging,

All processes that arise from

The twelve links of dependent origination,

We accept them to be like a dream and an illusion.

So here, Nagarjuna is saying things are like a dream or like an illusion, so I accept them to be like a dream and an illusion. They appear to exist truly, but they don’t exist truly. I’m not saying that phenomena exist truly, but they still perform a function. This function is merely labeled; it’s merely designated. Because it’s merely designated, how can we say there’s a function? Take a dream, for instance: when we dream, we might perceive elephants and horses and a garden, so at that time, whatever appears to the mind is merely labeled. It’s just an appearance to the mind. It doesn’t exist. There’s no garden there; we’re just dreaming about it. It’s merely designated by the conceptual mind. We may like it. It looks pretty, so we’re happy when we see this beautiful garden. And sometimes when there’s an elephant or a lion or a snake, we are scared.

Also, when we eat food we accumulate negative karma and positive karma. I benefit you; you benefit me. I engage in actions so that I won’t suffer and I’ll be happy. We do all these functions; we engage in certain activities that help us and things that harm. Sometimes there’s suffering; sometimes there’s happiness. This happens, but if we don’t really analyze it seems there’s something concrete there, some essence, that performs this function. But this cannot be found. So, this is where we apply correct reasoning, because phenomena don’t exist inherently. Phenomena not existing by way of their own nature can be understood on the basis of ultimate analysis. It depends on logical reasoning, so it can be understood. If we were to say that phenomena exist truly, that would be in contradiction. That would be contradicted by a lot of other facts. It would be contradicted by reality. Even if phenomena don’t exist truly, even if they don’t exist inherently, still they perform functions. We can see that there are certain activities, certain actions—you can do something. I can do something to you; you can do something to me. It’s our own experience.

Through this experience, for instance, if I beat you, you’ll have pain. So, from our own experience we can know that they exist. We don’t need to give reasonings for that. If I beat you, it hurts you. Why does it hurt? That’s just nature. We don’t need to analyze that. When I eat then I’ll be full at some point. Why will I be full? We don’t need to really analyze that. So, all these objects that appear to us, we can say they exist. We can perceive them. We can experience them. They harm us or they benefit us. From that point of view, we can say they exist. But there’s no other way in which they exist. There’s no other form of existence that they need, so therefore, the twelve links are like a dream or like an illusion.

To give you another example, when you build a house or a building with different rooms, they all look the same. It doesn’t matter if it’s the parent’s room or a child’s room or even an uncle’s room—to the person who builds the house, they look all the same. That’s especially true when you’re building the house. The rooms all look the same. Later we might designate one room as an uncle’s room, so because it was designated as the uncle’s room that’s why it becomes the uncle’s room. It performs the function of an uncle’s room. So, everyone else will not go into that room; only the uncle will go into the room, but it’s actually just designated from the side of the house. It’s merely labelled. It’s merely designated having decided this is the uncle’s room, and now it performs the function of an uncle’s room because only the uncle stays in there. No one else does.

For instance, everyone can recite the prayers, but not everyone will be the chanting master. In the monastery you always have a chanting master, and also you need someone who tells everyone else what to do, someone who looks after the younger monks. They all have certain qualities, but if no one gives them the position of chanting master then they won’t perform the actions of a chanting master. Only after they’ve been designated to be the new chanting master then they act as such. Likewise, with the person who oversees some of the monks, unless this person is designated to be such then they will not perform these actions. Because things are designated in a certain way, they function in that way. Therefore, phenomena don’t exist inherently. Phenomena cannot exist truly. That will be contradicted by logic. Existing inherently is not in accordance with reality, and logic will contradict that.

Phenomena exist. We can perceive them, we can know them, through our own experience. We can experience the things that do exist, but with inherent existence, that’s what we refute that is contradicted by logic. Because it logically doesn’t make sense, we can say it doesn’t exist. Me, you, houses, cars: we can all know that these objects exist. I can see you. You can see me. We can see a house. We can stay in a house. We can experience the house in that way. We say phenomena exist, like a building exists. We know this; we experience the building. We use the building; therefore, we say it exists. So, when it comes to how it really exists, we don’t need to give a lot of reasons. We can just say it exists, but with inherent existence it’s different. We cannot be positive about inherent existence because it’s in contradiction with reality.

What cycles through samsara?

Verse 60:

This wheel with twelve links

Rolls along the road of cyclic existence;

Outside this there cannot be sentient beings

Experiencing the fruits of their deeds.

On the basis of cycling within the twelve links, we label sentient beings. But outside of that we cannot talk of a sentient being. There’s also nothing else outside of the twelve links that experiences the fruits of their deeds, so how are we cycling? It’s inside the existence.

Verse 61:

Just as in dependence upon a mirror

A full image of one’s face appears,

The face did not move onto the mirror;

Yet without it there is no image [of the face].

When you have a reflection of a face in a mirror, it’s not like it’s been added onto the mirror. It’s not that it’s added there or that it was actually put there. It’s just natural that a mirror reflects a face. Likewise, it’s not like sentient beings are actually put in their next life. It’s not like they’re kind of inserted somewhere. It’s just this mind that continues on. This continuum of consciousness goes on to the next life. And depending on karma and so forth, we’re reborn.

Verse 62:

Likewise aggregates recompose in a new existence

Yet the wise always understand

That no one is born in another existence,

Nor does someone transfer to such existence.

For instance, take this object in front of me. It’s not like that this object unchangeably will be sitting there. Now I’ve moved this object. When I have an impermanent object and I put it on the other side then I transfer it. But in terms of rebirth, it’s not like there’s a transference really. It’s really just this mind that leaves the body, and the mind is changing, and it enters another body. So, it’s not transference as in someone puts this person somewhere else.

Verse 63:

In brief from empty phenomena

Empty phenomena arise;

Agent, karma, fruits and their enjoyer—

The conqueror taught these to be [only] conventional.

This is similar to a verse in Entering the Middle Way. That which accumulates karma, that which experiences the karma and so forth—these only exist conventionally. They only exist nominally. Existing conventionally is that which we experience. They exist conventionally.

Dependence on many different factors

Verse 64:

Just as the sound of a drum as well as a shoot

Are produced from a collection [of factors],

We accept the external world of dependent origination

To be like a dream and an illusion.

For instance, when we talk about the sound of a drum, we need certain factors. We need something like a stick that makes the sound, and we need a roundish kind of vessel, and we need leather on top that is tightly bound around it. There are a lot of factors that have to be complete in order to be able to make a sound with a drum. You need to have a person, and you need something that is beaten. And without this movement of the hand, you won’t be able to make the sound of a drum. All these objects coming together results in the sound of a drum. We have the result that is the sound of a drum because so many causes and conditions come together. Without oxygen, space and so forth, you wouldn’t be able to beat a drum.

Also, when you plant a seed, you need all these different factors in order for a sprout to grow. You need soil, fertilizer, warmth, and water. You need someone to look after the seeds and so forth. And then on the basis of all that then something arises. So, you have internal objects and you have external objects. They are all like dreams and illusions. External objects are like the seed and so forth: they arise on the basis of many causes and conditions—of the drum and the internal factors as well. Can there be sound if there is no ear consciousness? Without an ear consciousness, can there be sound? Could sound exist without an ear consciousness existing?

Can we say that because there is sound therefore there must be an ear consciousness? Not just that, but for instance, the mind is like a continuum without beginning or end. So, we can’t really distinguish. It’s all this continuum. When we take the continuum of a sprout, for instance, when it arises, a sprout is just a sprout for some time. It’s not like it doesn’t have a continuum that is beginningless and endless. Actually, in the continuum as a sprout, there is a beginning, but the continuum itself as a physical object has no beginning and no end. It’s a bit like a wave in the ocean. Sometimes it’s a sprout and sometimes it’s something else. So, like the wave in an ocean, it goes up and it goes down. The continuum of the sprout always goes on and always existed and will always exist. As a physical object, it has always existed and will always exist. Sometimes it arises as a sprout, but then it grows bigger. Then it becomes again a seed, and then again it grows into something else. So basically, when we talk about physical objects, there is no beginning and no end. And the same is true for consciousness. The mind is not always born. It’s not aging and not getting sick and so forth. We’re talking about just a continuum that’s always there, that has no beginning and no end. This clear and knowing entity called the mind or consciousness doesn’t come into existence. That basic characteristic doesn’t come into existence, and it doesn’t go out of existence. The mind is always clear and knowing, so really, can we say it has come into existence?

Of course, the body—on the basis of which the mind exists—is different. Sometimes it’s this body; sometimes it’s another body. On the basis of the elements of father and mother—the ovum, the seed from the father and so on—on the basis of that, you have a body. And the consciousness is connected to different bodies, but for the mind itself, the consciousness itself, its basic nature doesn’t disappear. It has always been there; it will always exist. This is what verse 64 is saying.

Then verse 65 says:

That phenomena are born from causes

Can never be inconsistent [with facts];

Since the cause is empty of cause,

We understand it to be empty of origination.

So, even though the cause doesn’t exist inherently, it exists as a cause. But it doesn’t exist by way of its own nature as a cause because it’s dependent on an effect. In dependence on an effect, it’s a cause. Likewise, for instance, a son or a daughter are in relation to their parents, their son and their daughter. You couldn’t have one without the other. There’s mutual dependence.

Ultimate and conventional truth are not contradictory

Verses 66 and 67:

The non-origination of all phenomena

Is clearly taught to be emptiness;

In brief the five aggregates are denoted

By [the expression] “all phenomena.”When the [ultimate] truth is explained as it is

The conventional is not obstructed;

Independent of the conventional

No [ultimate] truth can be found.

When the ultimate truth is explained as it is, the conventional truth is not obstructed. There’s no contradiction to conventional truth; they don’t contradict each other. Both exist equally in dependence. If we understand cause and effect and so forth, then we overcome the extreme of nihilism. This is what it said earlier. So, when we talk about the five aggregates, that refers to conventional truth, but it doesn’t harm the ultimate truth because they’re not contradictory. Independent of the conventional, no ultimate truth can be found. They are of one nature. Conventional truth and ultimate truth are of one nature. They depend on each other. Here we’re talking about emptiness; that’s the ultimate truth. So actually, without one you can’t have the other.

The ultimate truth doesn’t exist without conventional truth, and the conventional truth doesn’t exist without ultimate truth. For instance, in Tibet, some philosophers say that emptiness is not of the same nature, but Lama Tsongkhapa says that the two truths are not of a different nature. They are of one nature. When we say they are of one nature, we don’t mean ultimately. They’re not ultimately of one nature because nothing exists ultimately. But conventionally they are of one nature. So, what Nagarjuna says is accepted everywhere: product and impermanence are of one nature. And the conventional is taught to be emptiness. Emptiness itself is the conventional. One does not occur without the other, just like being produced and impermanent.

Produced and impermanent are of one nature

Whatever is impermanent is also produced; whatever is produced is also impermanent. This is a produced object. Something we can point at, an object is produced, and therefore it’s also impermanent. Whatever is impermanent is also produced. So, being produced and impermanent are of one nature—it’s impossible to say being produced is over here and being impermanent is over there. It’s the same object, so if we cannot distinguish between two things from the point of view of their nature, are they identical? The Vaibhasika school says that if something is of one nature they have to be one. They cannot really distinguish that. So, they would say that if something is a phenomenon—where we say if something is both produced and impermanent—then they are of one nature.

Also, in the Pramanavarttika, it explains that even the phenomena of the same nature, of the same substance, are still different phenomena. We apply different terminology because they were produced by causes and conditions. We say something is produced and something is impermanent because it changes moment-by-moment. Therefore, we say it’s impermanent. So, there’s a different reason why we call something produced and impermanent, but then it cannot be separated because if something is produced by causes and conditions it has to change moment-by-moment. Therefore, both have to exist together. Something can only be impermanent because it has been produced by causes and conditions, and the other way around. But we still think of it as different; we perceive it differently. But that doesn’t mean that they are of different substances or of a different nature.

Different perspectives

Take one person as an example: this person is an expert and the disciplinarian. This person disciplines people, and this person is a scholar with great expertise. This person is also part of a family. Let’s say this person is called Töndrup. We could say it’s the disciplinarian Töndrup and the scholar Töndrup and Töndrup who’s part of this family. There are three different ways to describe this person. When we say this Töndrup who’s part of this family, or when we say this scholar Töndrup, it’s the same person. And when we say the disciplinarian, it’s the same person. Actually, they are the same person. These three ways to describe this one person Töndrup have no different substances; it’s the same substances, the same object. But still, when we talk about the disciplinarian Töndrup or the scholar Töndrup, they are not identical, but they are of one nature. Because some people know that he’s the disciplinarian, but they don’t know he’s the scholar. And some people don’t know he’s the scholar, but they know he’s the disciplinarian. There are different ways to perceive him. If the different ways people perceive him were one, you would have to perceive all these aspects of the person, but that’s not the case. Therefore, when we talk about Töndrup the disciplinarian or Töndrup the scholar, they are of one nature. But they are not identical. This is what it says here in this verse.

Verse 68:

The conventional is taught to be emptiness;

The emptiness itself is the conventional;

One does not occur without the other,

Just as [being] produced and impermanent.

Take the lid on this cup: from the point of view that it has arisen from causes and conditions, it’s a conventional phenomenon. From the point of view that it lacks inherent existence, from the point of view of the absence of inherent existence, it’s an ultimate truth. From the point of view of the fact that it arises from causes and conditions, we say it’s a conventional truth; from the point of view of the lack of inherent existence, we say it’s an ultimate truth. On the basis of one phenomenon, we can say that both exist, and they are of one nature.

The conventional world arises from karma

Verse 69:

The conventional arises from afflictions and karma;

And karma arises from the mind;

The mind is accumulated by the propensities;

When free from propensities it’s happiness.

By “conventional,” we mean phenomena that appear to us—the external environment, sentient beings and so forth. That’s called conventional. It’s in the nature of suffering, the nature of dukkha, so it arises from afflictions and karma. Actually, it’s explained separately. The conventional arises from karma, and karma arises from afflictions. That’s how it’s explained in some of the commentaries, but I don’t think it’s true. When we say the conventional arises from afflictions, the conventional here is described as afflictions. Because we talk about the conventional as the samsaric world, and that is affliction—affliction not as a mind but an affliction in another sense. When we say afflictions here, because it’s in the nature of suffering, we say it’s an affliction. From that point of view, the samsaric world, the conventional world that is in the nature of suffering is an affliction. It’s afflictive, and it has arisen from karma.

In this world there are so many living beings. There are so many sentient beings in this world, our home. All sentient beings have been born here; they have arrived here. They have arrived here in this world, so that’s in relation to karma. There needs to be a cause why sentient beings are born here, so that’s because of karma. And karma arises from the mind. The mind is accumulated by the propensities. We accumulate all kinds of karma, so that karma leaves imprints on the mind. Virtues and non-virtues leave imprints. From the afflictions and so forth, there are so many different imprints, so many different potentials. The mind has come into existence as a result of past karma, so the present mind is the result of past karmic actions that were also accumulated by the past mind and so forth. When we benefit another person out of attachment or when we harm another person out of attachment and we accumulate karma, it’s this mind that is controlled by attachment that accumulates karma. And that mind is the result of previous types of mind of the previous continuum that also accumulated karma.

Bodhicitta and emptiness

So, on the basis of the extreme attitude that exaggerates the existence of things, on that basis, karma was accumulated and created the present mind. It’s because of ignorance and the afflictions and so forth—on the basis of that, the present mind arises. If we really understand that, it’s very profound. Mind accumulates karma, mind is under the control of the afflictions, but where does the mind come from? It also comes from previous minds, from different imprints. And where did these imprints come from? They come from familiarity. Sometimes people say the familiarity itself is the imprint. These imprints are that which created the present mind, so when free from propensities, it’s happiness. It’s karma that created our present mind from these propensities, from these imprints, as a result of the afflictions. So, the continuum of the mind that has existed since beginningless time, this present mind under the control of the afflictions, the cognitive obstructions, the extreme attitude and so forth: if we were to eliminate these propensities—all these imprints: this familiarity, these afflictions and so forth—then we would experience happiness. Then it says a happy mind is tranquil indeed. A tranquil mind is not confused, so the fewer propensities, the fewer imprints, we have, the less ignorance there is. What makes the mind non tranquil, what confuses the mind, is ignorance. If the defilement of ignorance is gone then we understand the truth.

What does that mean? If our mind right now is under the control of afflictions, that’s samsara. If we overcome the afflictions, if we realize emptiness, that’s liberation. As long as you grasp at the self then we’ll have samsara. By understanding the truth one attains freedom. It’s described as suchness and as signlessness and as the ultimate truth. All these are the ultimate truth: the supreme awakening mind. It’s described also as the emptiness, so here we say the ultimate. We say it’s the ultimate; it doesn’t go further. It’s the limit of reality. That’s the ultimate truth or that’s emptiness.

Of course, there are a lot of different types of suchness, a lot of different kinds of reality. For instance, impermanence, being produced, suffering, conventional truth: these are all realities. But the actual final reality is emptiness, so it’s the limit in that sense. It’s the ultimate truth, signlessness. With conventional truth, you have a lot to perceive: “It’s like this,” “It’s like that.” There are all these different characteristics, but when it comes to emptiness there are no signs. It’s their signlessness. And when we say the ultimate truth here or the ultimate meaning here as the supreme awakening mind, it’s described also as the emptiness. So, when we talk about the object—suchness, the limit of reality, signlessness, the ultimate truth and then the mind—what is the mind that perceives emptiness? That’s ultimate bodhicitta. It’s the mind that realizes emptiness directly. That’s the ultimate awakening mind. We say the mind that realizes emptiness directly is like pouring water into water. The mind is so absorbed into emptiness there’s no sense of the mind and it’s object. The mind is non-dual, and it’s like mind and object are water being poured into water. This supreme or this ultimate awakening mind is also sometimes described as the emptiness. Sometimes we also apply the term emptiness to the mind that perceives emptiness.

Verse 72:

Those who do not understand emptiness

Are not receptive vehicles for liberation;

Such ignorant beings will revolve

In the existence prison of six classes of beings.

Without understanding emptiness, we will not become liberated, so these six classes of beings remain in the prison of existence because of not realizing emptiness. This is important because the root of samsara is the mind that grasps itself: the mind that grasps at the self of phenomena and the self of a person. When we talk about grasping at the true existence of phenomena, without realizing emptiness we don’t understand selflessness. We don’t understand emptiness. We cannot overcome samsara. There’s a lot of debate on that between different philosophers.

We’ve been talking about emptiness that’s free from all fabrications. Next we’ll be talking about conventional bodhicitta.

Part 3 in this series:

Part 5 in this series:

Yangten Rinpoche

Yangten Rinpoche was born in Kham, Tibet in 1978. He was recognized as a reincarnate lama at 10 and entered the Geshe program at Sera Mey Monastery at the unusually young age of 12, graduating with the highest honors, a Geshe Lharampa degree, at 29. In 2008, Rinpoche was called by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to work in his Private Office. He has assisted His Holiness on many projects, including heading the Monastic Ordination Section of the Office of H. H. The Dalai Lama and heading the project for compiling His Holiness’ writings and teachings. Read a full bio here. See more about Yangten Rinpoche, including videos of his recent teachings, on his Facebook page.