Moving from the heart

By Tracy Lee Kendall

Tracy Lee Kendall writes about how another person in prison, Cory, moved their Dharma group deeply through his honest sharing about having stage four cancer. Learn more about Tracy here.

We constantly move through each other, throughout life and beyond as our bodies, minds, art, technologies, music, words, dreams, and other dynamics forge a human world in the universe. Within this context, we can become desensitized, feeling our movements through each other less and less. Yet at times, we move through each other in such profound ways that our hearts are touched enough to feel more deeply, and new potentials of our humanity are unlocked, as I experienced on March 24, 2023.

Cory1 had returned to the Beto Unit Eastern Religions Service after a number of absences for health and personal struggles. There, Cory opened up his heart to us about stage four cancer in multiple parts of his body, his fears, his love, and everything else evoked in human minds by such circumstances. Then he emphasized: “What I am going through is no worse than what any of you are going through.” This stunned everyone in the group, and for a while, there was only silence. We sat in the concrete and steel sanctuary, decorated with paintings of baptism, a prostitute, supper, and what someone posited as the end of all things.

Soon, I found us all standing in a small circle of eight different people—formerly entertainment workers, military personnel, career criminals, drifters, businessmen, and others from a variety of locales, who prison brought together. Although I cannot remember how or when, I know it was Cory who moved us to stand. In our desperation, each of us struggled to offer him something of comfort, and while the offerings were pleasant, nothing was truly moving at first.

In Texas prisons, the majority of inmates attempt to impose a desensitized culture to help normalize corruption such as drugs and violence they capitalize on.2 Concurrently, the system itself affects desensitization among staff and inmates to maintain security and cut corners with less repercussions. This environment can make people feel numb inside to varying degrees. The resulting numbness restricts our ability to move through each other in positive ways, yet perpetuates the ability to have negative impacts upon others.

Ironically, with all of the rhetoric moving through the general public about rehabilitation in prison, actual practice can be counterproductive to such efforts, including the capacity for people to contribute to each other. So we inmates often struggle whenever we want to reach out effectively to another human being, especially during times of adversity. Yet this is not because it is hard for us to care. Rather, the problem has to do with prison culture obstructing us from our feelings (which are a catalyst of our movements through each other). So because of the inherent desensitization normalized in prison, it is harder for us to reach our own feelings and share them.

Since our movements through each other are synonymous with the facets of humanity we share with each other, there are no movements in our human context without sharing. This was confirmed initially, as we remained frozen in our shoes on March 24, 2023. Then a correctional officer came in to count us. As he was counting, Cory moved to embrace us, and I stood there and held him against me as he cried the most sincere tears I have ever witnessed in another human being. He has no idea what will happen to him (and is actually at risk because this unit lacks adequate facilities to treat cancer), does not want to die, and has dreams like anyone else. Yet in those moments, he moved through all of us, sharing everything he is and loves to show us compassion.

Cory’s movement contributed to our ability to share with each other more deeply. Instead of focusing upon himself, he continually reminded us of our value, what we mean to him, and the significance of a woman in the free world he calls his “cancer buddy.” (She is also battling cancer, and reciprocates hope with Cory) So despite of our desperation to help Cory in some way, he ended up enriching our lives. And we were able to move through and with each other for the rest of our time that day in the sanctuary of one of the worst prisons in Texas. This movement reinforced our ability to better share with others in the future.

This is the heart everyone should have, that no matter what we are going through, we never lose our empathy and compassion for others. The movement that enriches all it touches, from the moment of contact and beyond. With such a profound example, we decided to name our group “Cory’s Heart Sangha” (Sangha is a Sanskrit word, basically meaning “association,” with a connotation of interdependence). Thus, wherever Cory’s journey takes him, he will continue to make the world a better place as the seeds of his compassion grow through the lives he touched and beyond.

Like Cory, we all have the ability to open ourselves up and move through others. Some people choose to move with corruption, violence, and predation, which perpetuates events and cycles of devastation. Others choose to move in profound ways with a paintbrush, or a song, or a cure, or in other ways that bring life and joy to the world. While Cory is a fighter (his motto: “Enjoy life while you can, fight when you have to”) he opened his heart in the most painful (physically and mentally) and uncertain period of his life and cared for us. By expressing his profound love, he set an example which changed our lives, and the lives of everyone who we open ourselves up to.

In the context Cory intended, “What I am going through is no worse than what any of you are going through,” could move our divided world into unity. And if we all had Cory’s heart moving through us, where would we be? Definitely moving with each other—in our dreams and even beyond, forging new potentials of life, compassion, and empathy on our journey together.

Cory’s name has been changed for privacy reasons. ↩

Ven. Chodron had some further questions for Tracy about this sentence that he responded to:

Q: Who is capitalizing on drugs and violence: the inmates? the guards?

A: Both, but my focus in the statement was more on the inmates. It is relevant in the story because Cory did the exact opposite of that, with the exact opposite results. He gave of himself, instead of took, and we received life, rather than suffering.

Q: What is meant by “capitalize”?

A: It means to receive assets and/or power through the perpetuation of a predatory environment wherein they secure key positions from which they can benefit. The lure of drugs and fear of violence are the key factors which allow them to exploit other inmates.

Q: What does “desensitized culture” mean?

A: One wherein drugs, violence, and other criminal corruption is seen as the norm, rather than anything surprising or to be resisted or changed. Once people are desensitized, they more easily engage in violence and crime and also consider it abnormal and even wrong to stop doing it, or prevent others from engaging in it. Once this norm is established in a prison system, it is conducive to the agendas of those who wish to capitalize on others in a multitude of ways. It also creates a Hell on Earth wherein all of this behavior is considered as good. ↩

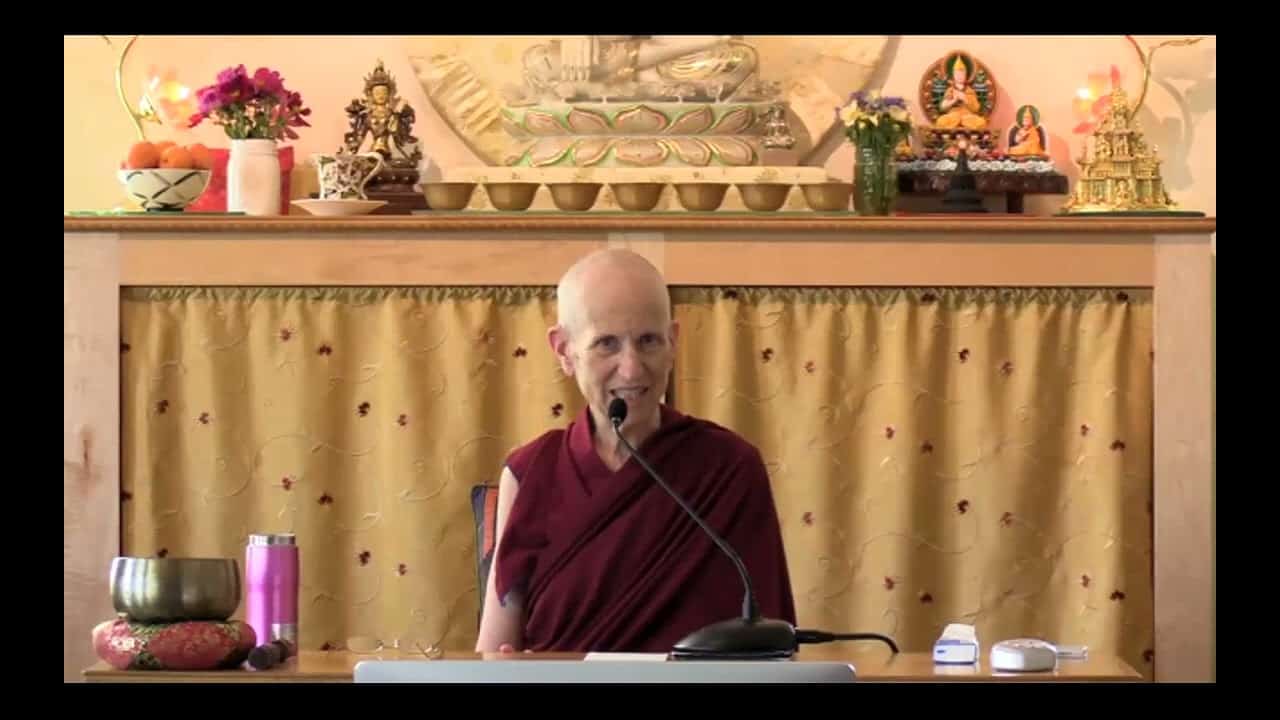

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.