The Buddhist path and emptiness

01 The Wisdom of Emptiness

A series about emptiness hosted online by Thubten Norbu Ling in 2021.

- Overview of the Buddhist path

- Four Noble Truths

- Three Higher Trainings

- Samsara

- The Two Truths:

- Conventional and ultimate

- The four systems/schools of Buddhist philosophy

- Two aspects of the Path to Enlightenment:

- Wisdom and method

I’m very happy to have this opportunity to talk about this topic. It’s a really, really precious and important topic, but I don’t want you to think I’m an “expert.” I’ve been studying for many years and have been fortunate to receive teachings from many wonderful teachers on this topic. I can definitely see that my knowledge and my understanding have grown over the years, but it’s a very complicated topic. I’ll just do the best I can and hopefully make it more clear for you. Just don’t expect me to know all the answers to your questions and to have perfect understanding. [laughter]

We’ll start with some prayers. As always, when we listen to Dharma teachings, we need to have a good state of mind. We need to have a positive attitude and a positive motivation, so the prayers help us to get into that positive state of mind. We take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha and generate love and compassion and altruism with respect to other beings. We’ll say these prayers and then spend a few minutes making sure that we do have a positive, altruistic motivation for participating in this class.

While reciting the prayers, I invite you to imagine the Buddha in front of you. You may find it difficult to do that, but it’s very helpful to feel that we are sitting in the presence of the Buddha. And we can also imagine there are many other buddhas and bodhisattvas around him and around us. Lama Zopa Rinpoche said, “All the time, wherever we are, there are many buddhas and bodhisattvas around us feeling love and compassion for us and wanting to help us.” So, we’re never alone.

The way that the buddhas want to help us is to help us be free of all of our mental and physical suffering and the causes of suffering, which are mainly afflictive states of mind, such as attachment and anger. But the main problem is ignorance: not knowing how things really exist, not knowing the true nature of things. The topic we’re looking at in this course is the direct antidote to ignorance. It’s like the medicine, the cure, for ignorance, and if we can cure our ignorance then we’ll be able to free ourselves from all suffering and causes of suffering. And then we’ll be able to help others do the same. Those are just some thoughts you can have in your mind as you recite these prayers.

Prayer of refuge and bodhicitta

I go for refuge until I am enlightened

To the Buddha, the Dharma, and the supreme assembly.

By my practice of giving and other perfections,

May I become a Buddha to benefit all sentient beings. (3 times)

The four immeasurable thoughts

May all sentient beings have happiness and the causes of happiness.

May all sentient beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering.

May all sentient beings be inseparable from the happiness that is free from suffering.

May all sentient beings abide in equanimity, free from attachment for friends and hatred for enemies.

Seven-limb prayer

The seven-limb prayer consists of seven different practices that enable us to purify our mind from negative karma, obscurations—all the negative aspects of our mind. At the same time, it also enables us to accumulate positive energy or merit. So, those two practices—purification and accumulation of merit—are important complementary practices to our study, learning and meditating on a topic like emptiness. They boost our practice so that it’s successful.

Reverently, I prostrate with body, speech and mind;

I present clouds of every type of offering, actual and imagined;

I declare all my negative actions accumulated since beginningless time

And rejoice in the merit of all holy and ordinary beings.

Please, remain until the end of cyclic existence

And turn the wheel of Dharma for living beings.

I dedicate my own merits and those of all others to the great enlightenment.

Mandala offering

The mandala offering is imagining all the beautiful, precious, enjoyable things that exist in the world and the universe, gathering them together, transforming them mentally into a pure land, offering that to the Buddha, and then having the aspiration that all living beings be able to experience the pure land.

This ground, anointed with perfume, strewn with flowers,

Adorned with Mount Meru, four continents, the sun and the moon,

I imagine this as a buddha-field and offer it.

May all living beings enjoy this pure land.

Idam guru ratna mandalakam niryatayami

(I send forth this jeweled mandala to you precious gurus)

Mantra of the Buddha

Now, let’s recite the mantra of the Buddha a few times. You might want to imagine rays of light streaming from the Buddha into yourself. You can also imagine them going out in all directions and going to all living beings everywhere. The light fills us completely, and it’s like an internal shower clearing away our negative karma and deluded thoughts. All the negative energy we have within us gets washed away, cleared away, just like when we take a shower and wash away the dirt from our body. This light also nourishes our positive potential. We all have positive qualities and good karma. You can imagine light nourishing the goodness we have within ourselves so that it can grow more and more and help us make progress on the path to enlightenment.

Tadyatha om muni muni maha muniye svaha

Cultivating our motivation

Now take a few moments to look at your state of mind. When we listen to Dharma teachings, ideally we try to keep our mind attentive, not distracted thinking about other things. Although that’s difficult to do for an extended period of time, if we start off with the intention or the resolution that we will keep our minds attentive, focused and not wandering elsewhere then that can help us. Even if our mind does get distracted, it will be easier to bring it back.

It’s also important to have a positive motivation, a positive intention. If you’re familiar with the idea of becoming enlightened just like the Buddha, attaining the same state the Buddha attained in order to be of benefit to all living beings, if you’re familiar with that and comfortable with that, you can think that that is your motivation for attending this talk and listening to these teachings. You want to eventually become a buddha so that you can benefit all living beings, and wisdom is one of the qualities we need to develop in order to become a buddha. We need to transform our mind into the mind of a buddha so then we can work to help all other living beings to become buddhas as well. If you’re comfortable with that motivation, you can remind yourself of that, bring that back into your mind.

If you’re not so familiar with that kind of motivation, or if you’ve heard of it but you’re not sure if that’s something you want to do or are even able to do, that’s okay. Try to at least have an altruistic intention, meaning you want to benefit others with what you learn from this talk. We do all have a wish to benefit others. It may not be there every minute or every second, but at certain times, we do feel the wish to help other beings—to relieve their suffering and bring them more peace and happiness. So, recall that feeling, bring that back into your mind and into your heart. And then you can connect that with our class. You can have the aspiration that you would like to learn things in this course that will help you to be more helpful to others.

The importance of emptiness

As I said, I was very happy to have the opportunity to teach this course because the topic we’re looking at, the wisdom of emptiness, is really, really important. If we want to attain buddhahood, enlightenment, it’s crucial that we understand emptiness. There’s no way to become enlightened without understanding emptiness. It’s also crucial for the attainment of nirvana or liberation, which is freedom from all suffering and the causes of suffering. It’s even important for our happiness and peace of mind here and now, in this present lifetime. So much unhappiness, so many problems, occur because we don’t understand things correctly. We see things in mistaken ways, ways in which things don’t exist.

The more we can learn about this topic of emptiness and investigate the way we see things, the more we ask ourselves, “Do things really exist that way or not?” The more we can do that, then the more we will also experience more peace in this lifetime and also fewer problems and difficulties in our relationships with other people, both our family and friends and neighbors and our boss and so forth. I will talk about how we can use these teachings on emptiness in practical ways to improve our lives here and now in this course also.

Slow and steady progress

This topic is important, but it’s also very difficult. It’s not easy. It’s probably one of the most difficult topics in the whole of Buddhism. And we only have five weeks. [laughter] That’s really short. Just to give you some idea, in the Tibetan monasteries, at least in the Gelug tradition, monks and nuns spend many, many years studying. They first study more basic, fundamental teachings, a kind of overview of the Buddhist path to enlightenment. They probably study those more basic philosophical topics for about twelve years before embarking on the study of emptiness using the text by Chandrakirti called Entering the Middle Way. The main topic in that text is emptiness. They spend four years studying just that one text, and they study five days a week, not just one day a week. [laughter] They study for five days a week for four years, and they memorize the text before they even begin studying. And then they are also debating it with each other. That’s pretty intensive, right?

Even after that much time, you might think they understand emptiness really well, but I’ve had a few encounters with monks who have spent that much time studying emptiness, and when I say this to them, they say, “No, no, no!” [laughter] It’s so difficult. Maybe they are just being humble; I don’t know. But it just kind of shows you that it’s not easy. It’s not something we can quickly and easily grasp and be fluent in. I’m not telling you that to scare you away but just to warn you that it is difficult, and it does take time and effort, so that you don’t have unrealistic expectations that after just five weeks you’re going to have a perfect understanding of every single aspect of emptiness and no more doubts or questions. [laughter] Don’t have that expectation.

Sometimes we can also get frustrated. That was definitely my experience when I first started learning Buddhism, and when I heard or read something about emptiness, I just didn’t understand anything. It was almost like it was another language that I didn’t understand. I couldn’t make any sense of what I was hearing or reading. But I didn’t give up, and slowly, slowly, over the years, things started making more sense. I started getting more understanding of it. And now I’m even at the point where I can talk about it. [laughter] I can give talks about it and explain it to other people. If you don’t get frustrated and give up but keep trying, then slowly, slowly it does start to make sense. Your questions will get answered.

The four noble truths

Before we jump into the actual topic of emptiness, I would like to start with an overview of the Buddhist path because I don’t know who is following this course and whether you’ve done in-depth study of Buddhism. Perhaps you have, but some of you might be new, and even if we have studied for many years and we know a lot about Buddhism, it doesn’t hurt to hear basic teachings again. Like if I was going to talk about the four noble truths, we might think, “Oh, the four noble truths, yeah. I’ve heard that before. I know that.” But actually, the four noble truths is very deep. We can go into a lot of depth with the four noble truths. It’s not that easy. So, it doesn’t hurt to hear those teachings again and again. Each time we do, we might learn something new. Also, in talking about this overview of the Buddhist path, I want to show where this topic, the wisdom of emptiness, fits into the overall structure of the Buddhist path.

The first topic we’ll look at is usually called the four noble truths, but a more accurate translation is the four truths of noble ones. It isn’t that these four things are noble. That’s a little strange—especially the first one, duhkha. Suffering is noble? Is there anything noble about suffering? That’s not really an accurate translation. Rather, these four things are called the four truths of noble ones. The Sanskrit term for noble ones is aryas. An arya is a person who has attained the realization of emptiness, not just an intellectual understanding of emptiness. We do have to start by having an intellectual or conceptual understanding, but then we have to continue meditating on our understanding until it becomes a direct realization. A direct realization means our mind is directly experiencing emptiness. That’s quite amazing. I’ve not attained it. [laughter] I’m definitely not there. But when a person does have that realization, it’s really amazing and incredible.

When a person does have that direct realization of emptiness they are given this name “arya.” It means “a noble one.” Sometimes it’s translated as “superior,” but I’m a little uncomfortable with that term. I like the term noble one or just arya. So, these are four truths of noble ones, meaning that for those beings who have directly realized emptiness, these four things are true. They know these four things to be true. And for those of us who are not aryas, who have not reached that level, these four things are not necessarily true. [laughter] In fact, a lot of people might disagree with these four things and think, “Oh no, that’s not true! That’s false!” Anyway, from the point of view of the aryas, those who have direct realization of emptiness, they really know how things are. They have a very clear and correct understanding of things. They know that these four things are true.

The first one is true duhkha. You’ve probably heard it referred to as “true suffering,” but I’m using the Sanskrit term duhkha because the term “suffering” is a little misleading. In English, when we hear the word “suffering,” we usually think of really terrible things, like war or grief when somebody loses a loved one or physical pain or terrible diseases like cancer. It’s usually something really extreme and awful; that’s our usual connotation of the word “suffering.” Whereas the term “duhkha” does include those extreme cases of suffering, but it also includes experiences that most people wouldn’t consider suffering at all. We might even think they are pleasurable. [laughter]

A more accurate explanation of duhkha is any kind of experience that isn’t completely satisfying, that’s not wonderful and satisfying. Some teachers use the term “unsatisfactoriness.” That’s actually a better term than suffering. But I’m just mentioning all those different terms there because you do encounter them in different books or by different teachers. This point then refers to any kind of experience that isn’t completely perfect and wonderful and satisfying. All beings who haven’t yet attained nirvana or enlightenment are still just ordinary beings. That definitely includes me and most other beings. I don’t know about you. Some of you might have attained nirvana, but I haven’t. [laughter] And samsara has the meaning of cycling—going through a cycle, going through a cycle. And the cycle is death and rebirth, so we are born, we live, we die, and then again we are born, we live, we die. So, for those of us who are still in samsara, we keep going through this cycle of death and rebirth again and again and again without any choice or control.

Three kinds of duhkha

That’s the rough meaning of samsara: that kind of existence. So, all the beings who are in samsara do experience duhkha. Nobody is free of duhkha. Everyone has duhkha. And there are different kinds of duhkha, but they can be included in three categories. There’s this list of three types of duhkha. The first one is the duhkha of duhkha or the duhkha of suffering. Or the suffering of suffering. [laughter] That one just refers to gross experiences of suffering that everybody recognizes as painful, unpleasant, undesirable. Again, this is physical pain and sickness and emotional suffering, like being depressed or being lonely. This is feeling grief over the loss of a loved one or the loss of a job. There are many different kinds of mental suffering that people can have. As soon as we have that kind of experience, nobody has to tell us, “This is suffering.” We know it. We are suffering, and we want to be free of that experience.

Even animals are aware of this kind of suffering. They don’t like being cold or hungry or abused. So, they try to avoid those kinds of experiences. That’s easy to understand. There’s no challenge to understand that. And then the second kind of duhkha is called the duhkha of change, and this refers to experiences we have that appear to be pleasant and enjoyable but because they’re impermanent—they last a short time and then they disappear—they don’t completely satisfy us. So, they are considered another kind of duhkha. Here the word “suffering” doesn’t seem quite appropriate whereas “unsatisfactoriness” is a better term.

An example is eating food. Most people like to eat, and we have to eat to survive. When we’re eating, we usually feel a lot of pleasure and enjoyment. We think, “This is great. This is a nice experience. I enjoy this.” Of course, we can also get very attached to eating food and want to eat more than we need and so on. So, it can be the cause of suffering in that way. But even if we don’t have attachment, just the fact that it’s temporary, that the pleasure of eating food only lasts for a limited amount of time and then it’s over and then a few hours later we’re hungry and need to eat again, means the pleasure of eating isn’t fully satisfying. It doesn’t really remove any problems or suffering that we have. It just gives us a temporary respite from our suffering. It doesn’t eliminate our suffering; our suffering is still there.

Also, it can lead to suffering if we don’t know when to stop. We overeat and then we can have the suffering of indigestion or obesity, and that can lead to health problems and so on. If we look carefully and analyze what appears to be the pleasure of eating food, we can see that it’s not real pleasure. It’s not lasting pleasure. It’s not real satisfaction. And there’s the potential there to turn into suffering. It can turn into suffering. This is true for all the experiences we have that appear to be pleasurable experiences. They’re not fully satisfying. And they can even turn into suffering.

Another example is traveling. A lot of people love to travel. They go to different places and see the sights in that place, tour the food, go to the markets and buy all the interesting things. I’ve been there and done that. [laughter] I know what traveling is like. And there is some pleasure in having those experiences, but again, it’s short-term. It doesn’t last. And it can also turn into suffering in the sense that you don’t always have pleasant experiences when you travel. You can also have unpleasant experiences. And we’re still left where we were before.You come back home, and you have all those photos that you’ve taken and all these souvenirs that you’ve collected to show your friends, but has anything really changed in your life? You may have learned some things and had some nice experiences, but when it comes to our suffering in samsara, it’s still there. It hasn’t really gone away.

That is not easy to understand, and we probably feel a lot of resistance to it because we don’t like hearing that our enjoyments are not really enjoyable or are not real pleasure. We like to think, “They’re real pleasure. They really are pleasurable.” We’re quite attached to them and want to keep doing them. But in the Buddhist point of view, they’re not really pleasurable in the sense that they don’t last. But there is true happiness. There are wonderful experiences that do last. That’s the happiness of nirvana, the happiness of enlightenment. Those experiences are unceasing happiness. It’s happiness that doesn’t disappear after a few seconds or a few hours. It just keeps going. That kind of happiness does exist, and we can achieve it if we are willing to put in the time and energy. So, prepared with that kind of happiness, we can see that samsaric happiness, samsaric pleasure, is not really that great. In fact, it’s another kind of unsatisfactoriness.

The third of the three types of suffering is one that is even more difficult to understand, and it has a rather complicated name, which is “pervasive, compounded duhkha.” This refers to our very existence in samsara. It’s just the fact that we are in samsara. We’re not free from samsara. What it means to be in samsara is not a physical or geographical location. It’s not like planet Earth is samsara and nirvana is somewhere else. Samsara is actually our body and mind, what we call “aggregates” in Buddhism. The term “aggregates” refers to this combination of body and mind that we have. So, this very body and mind that we have, that’s sitting here now and listening to this talk, is samsara. This is samsara.

Our body and mind, according to Buddhism, don’t come about through some perfect causes and conditions. For example, many people believe in a God, a creator, who is perfect and loving and all-wise and all-knowing and so forth. They believe he created us and the world. And so, since we were created by a perfect being, we, too, are perfect. Well, if you really analyze that, you see a lot of flaws. [laughter] I was raised with that belief, and I saw a lot of holes with it. “What do you mean? This world is terrible! There are lots of problems in this world. It’s not perfect.”

According to Buddhism, where we come from, the causes and conditions that brought us into existence as well as the world and everything happening in the world, are basically two things. We get into these two things with the second noble truth, true origins. They are first, afflictions—afflictive emotions or delusions, like greed, hatred, ignorance and so on. These are mistaken, deluded states of mind. And then second, karma—contaminated karma that we created in a past life under the influence of afflictive emotions. So, we are the product of contaminated karma and afflictions. And those are very imperfect. [laughter] They aren’t perfect at all, and since the causes for existence are imperfect, we are imperfect. Our body and mind is imperfect. Our life is imperfect. Our world is imperfect. We come about through imperfect causes and conditions. And we’re under the control of these. We’re not free. As long as we’re in samsara, we’re never completely free of these causes of suffering: afflictions and karma.

Our whole existence is pervaded by afflictions, by suffering. That’s the meaning of number three: pervasive, compounded suffering. It’s not easy to understand. You do need to learn and think about and meditate on the Buddha’s explanation of things and learn to really understand it, but they say that’s the most important one to understand. It’s just to realize how we and all other ordinary beings in samsara, our whole existence, our individual life and our experiences as well as the world around us, is all pervaded by suffering and the causes of suffering. Because if we can understand that, we really want to get ourselves out.

Samsara is like being in prison. Nobody likes being in prison. Everyone likes their freedom. So, if we can recognize that we are like in a prison, that we’re not free, then that will give rise to this wish to be free, which we call renunciation or the determination to be free. That’s the reason for learning about and meditating on this first noble truth, or true duhkha. It’s so that we get ourselves out. We first have to have the wish to get out, and then we have to do certain things in order to get out. But first we have to wish to get out, and that wish to get out comes by understanding duhkha and how much duhkha there is in the world and in ourselves.

The causes of duhkha

Fortunately, it’s not permanent. There is a solution, which leads us to the second noble truth: true origins of duhkha or true causes of duhkha. What are the causes of all this duhkha, all this suffering? It’s two things mainly: number one is contaminated karma and number two is delusions. Sometimes delusions is called “afflictive emotions,” but I like the term “delusions.” These are states of mind that are mistaken and don’t see things correctly. They disturb our mind. There are things such as anger, hatred, attachment, greed, jealousy, arrogance. Those are some of the chief delusions. But ignorance about the true nature of things is the main delusion. That’s the root of all the other delusions.

To understand how these causes of duhkha do give rise to duhkha, ideally one understands the twelve links. The detailed explanation of this is in the twelve links of dependent origination. But in a simple way, you can say that within our minds there is ignorance about the true nature of things. There’s ignorance about our own self, our “I” and how we exist, but we also have ignorance about how everyone and everything else exists. So, we see everything in a mistaken way. Under the influence of this ignorance, we get caught up in afflictive emotions. We have attachment, desire, clinging for people and things that we find attractive and want to keep close to us. And we also have aversion, anger, hatred towards people and things that we find unpleasant and want to keep far away from us. We might even feel like doing something destructive to them.

Those are the two main afflictive emotions that arise in our mind. And then under the influence of these afflictive emotions, we act. We do actions, and if our actions are nonvirtuous actions, like killing, stealing, lying, speaking harshly, cheating and so on, then we’re creating karma. And it’s contaminated. The meaning of that term “contaminated” is “contaminated by ignorance,” which means it’s kind of under the influence of ignorance; it’s not free of ignorance. So, that karma we create becomes the cause for us to continue being in samsara, taking rebirth, experiencing samsara again and again and again and again. Those are the two main factors that are the cause of being in samsara and experiencing the duhkha, the unsatisfactoriness, of samsara.

True cessations

Then the third noble truth is true cessations, and a cessation here refers to the stopping of at least a portion of one of the delusions. It is possible to eliminate these delusions in our mind. Ignorance, greed and hatred can be eliminated such that they never arise again. And that’s the meaning of “cessation.” But it doesn’t happen all at once. It’s not like all of our delusions get wiped out in one go. Rather, it happens in a gradual way. So, when a portion of a delusion has been eliminated from the mind such that it will never arise again, that’s the meaning of true cessation.

That may sound kind of abstract, but we might get a little understanding of it if we can think of a time when our mind may have felt very peaceful. Maybe it was during meditation or when you were out in nature in some beautiful place or by the sea, but you just feel totally peaceful. You weren’t angry at anybody; you weren’t dissatisfied with anything. You weren’t restless and wanting something. You just felt completely peaceful at that moment with where you were and what’s going on. That’s a little bit like cessation. But it usually doesn’t last, right? [laughter] Sooner or later, something happens. We start getting restless and want to be somewhere else or doing something else. Or something happens that triggers off our anger and our irritation. That moment or those moments of peace usually pass and once again our mind gets afflicted. But just having a moment of that kind of experience can give us an idea of the meaning of cessation.

The way to attain that is by realizing emptiness. Like I mentioned before, the aryas, those who have the direct realization of emptiness, are the ones who experience cessations. When they have that direct realization of emptiness that is the thing that eliminates the delusions in the mind. So, they are gone forever and will never come back. It’s only aryas that really have a true cessation. We can have little glimpses, little moments of that experience, but they don’t last.

And then the fourth noble truth is true paths. A “path” is actually a state of mind. It’s a realization. The main path is the wisdom that directly realizes emptiness. Again, that is what an arya attains. You do have to study; you have to learn about emptiness. You have to think about it for a long time before you understand it. And then you have to meditate on it. Gradually, your meditation on emptiness will lead you to the point of having a direct realization of emptiness. That’s the main true path. That direct realization of emptiness is what eliminates ignorance and the other delusions. It doesn’t do it all at once but gradually. That’s the meaning of a “true path” or “true paths.”

That’s just a brief overview. There’s a lot more that can be said about the four noble truths. There are a number of books written about them. There are books by Geshe Tashi Tsering and Lama Zopa Rinpoche that can give you more information, and there are books by His Holiness as well.

The three higher trainings

Then, the next point, letter B, is the three higher trainings. If we do feel this interest to get out of samsara and attain at least nirvana—further than that is full enlightenment, buddhahood—then what we need to do is follow the path. There are different ways of explaining the Buddhist path. For example, in the Tibetan Gelug tradition, there’s the lamrim, the stages of the path. But that’s specifically the path to enlightenment, to buddhahood. For those who want to attain nirvana, liberation, freedom from samsara, the path mainly consists of three things. This is the simplest formula to explain the path; it’s these three higher trainings: ethics, concentration and wisdom.

Ethics basically means refraining from harmful actions, such as the ten nonvirtuous actions. The ten nonvirtous actions are the physical actions of killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, telling lies, harsh words, divisive speech and idle talk. And then the three nonvirtuous mental actions are covetousness, malice and wrong views. Those are the ten nonvirtues that the Buddha advised us to refrain from because they create suffering. But even if it’s not in that list of ten, any action that is the cause of harm and suffering we try to refrain from. Of course, right from the beginning, we can’t refrain from every single harmful action. But we try to at least stop the worst ones, like killing. Maybe telling lies is not so easy to give up, but gradually as time goes on, we can reduce and stop harmful actions. That’s basically what ethics is all about.

In Buddhism, we also have this practice of taking vows or precepts, like monks and nuns have a set of vows that we take. But even people who don’t want to be monks and nuns but want to be family people and have relationships can also take vows or precepts. These are things like the five precepts for lay people. Taking precepts is really helpful because you make a promise to the Buddha. You say, “I promise I will not kill,” and that becomes very powerful. You think, “I have promised the Buddha that I’m not going to kill anymore,” so that really helps you even in situations where you might want to kill an insect or animals. You remember that promise. That will help you to stop. It’s a powerful way to stop ourselves from doing harmful actions, and it’s also a way to create a lot of virtue and good karma. Because when we take and keep precepts, we’re creating virtue all the time, 24 hours a day. We do need virtue. We do need good karma in order to have good experiences in the future and to progress along the path. So, that’s basically what ethics is about: refraining from harmful actions and doing positive, virtuous, beneficial actions as much as we can.

Next is concentration. That is training the mind to stay on our meditation object, whatever it is. It might be the breath or a visualization of the Buddha, or you might be meditating on impermanence or compassion or love. Whatever the object, we need to keep our mind on our meditation object rather than having it wander here and there, thinking about all kinds of other things. We do have a certain amount of concentration naturally. We can stay concentrated when reading a good book or watching a movie or football game. [laughter] People can concentrate on that very well. But usually our attention span is limited, and eventually we wander away. But it is possible to train our mind to have longer and longer periods of concentration on our object. Eventually we’ll be able to stay concentrated for hours on our meditation object without being distracted or falling asleep or anything like that. Developing concentration is a very important part of the Buddhist path.

Third is wisdom, and there are different kinds of wisdom, even different kinds of conventional wisdom. Wisdom is like understanding the law of cause and effect, karma, gaining some wisdom into that. Wisdom in general just means having a correct understanding of something. But usually when we talk about wisdom, we’re talking about wisdom of the ultimate nature of things, the true nature of things, which is emptiness. That’s very important. That’s what we need in order to become free of suffering and to obtain nirvana and enlightenment.

The third of these three higher trainings is the most essential one, but it’s also not easy to develop. So, one thing we need to develop wisdom is to be able to concentrate. [laughter] We need concentration because if our mind is scattered all over the place then it’s not easy to develop wisdom. Wisdom depends on concentration. But even concentration is not easy to develop. And so, as an aid, as a foundation for concentration, we need ethics. If we don’t have good ethics, if we’re not careful about our behavior and if we’re just acting in any old way and following whatever impulse is coming up in our mind, then we may be doing a lot of harmful and destructive things. We may be doing a lot of nonvirtuous things, and then if we’re living in that way and sit down and try to meditate, to keep our mind concentrated on our object of meditation, it won’t work very well. We’ll be thinking about all these things that we did and probably feeling some regret and some guilt and some worry and fear. Our mind will be very disturbed.

On the other hand, the more we can have good ethical conduct in the way we live our life, the more our mind will be peaceful and calm. Then when we sit down to meditate, it will be easier to concentrate. That’s why the three are arranged in this order. Ethics is like the foundation and then on top of that we can develop concentration and on top of that we can develop wisdom. That doesn’t mean you have to have perfect ethics before you work on concentration. We can work on all three at the same time, but the point is that we can’t do without the first one and the second one and think we can just skip over those and develop wisdom.

Questions & Answers

Before we continue, does anyone have any questions about anything I’ve talked about so far?

Audience: Thank you, Venerable. My question is concerning the lamrim versus the classic approach to nirvana. Does one pass through nirvana on the way to buddhahood or is it just kind of a lone path into full buddhahood?

Venerable Sangye Khadro: That’s a good question. In the lamrim, there are three main parts which are called three scopes usually. In the small scope—that’s kind of the initial level of the path—we learn about our precious human life and then death and impermanence, the fact that we’re not going to be here forever. We’re going to die one day, and after we die, we’re going to have another rebirth. And there could be an unfortunate rebirth if we’re not careful. That induces the initial interest in Dharma practice, trying to make sure that our next life will not be a bad one but will be a good one. And then the solution to that is learning about karma.

Then the middle scope is to think about the whole of samsara: cyclic existence, the four noble truths, how we’re in this situation of duhkha and afflictions and karma. We’re not really free. So, the middle scope section of the lamrim is basically about how to generate the wish to obtain liberation or nirvana, to get ourselves out of samsara. But for somebody who wants to go all the way to buddhahood, they don’t want to attain what’s sometimes called “self liberation” or “solitary peace.” That means that you are just liberating yourself; you’re getting yourself out of samsara and to the state of peace and that’s it. You stop there. In the Mahayana, which Tibetan Buddhism is a part of, we want to go further. We want to go to full enlightenment or buddhahood. We don’t want to go to just solitary peace.

However, even if you want to become a buddha, you do still have to eliminate the causes of suffering in your mind. You have to eliminate ignorance and all the other afflictive emotions like greed, hatred and so on. You do have to do that, and you do have to develop the wisdom realizing emptiness, which is the method to be free of suffering and the causes of suffering. But your motivation is different. Your motivation isn’t just to free yourself from suffering. Rather, it’s to reach buddhahood and help all other living beings to be free of suffering.

It’s a little complicated, but for a bodhisattva, meaning the person who wants to go all the way to buddhahood, there are different divisions of the bodhisattva path. I can explain this later if you’re really interested, but it can be divided up into what are called five paths. These are five different sections of your progress to buddhahood. And a further division is into what are called the ten bhumis or the ten grounds of the bodhisattva. When you reach the eight of those ten bhumis, you are at the same level as an arhat, as somebody who has attained nirvana. So, your mind has become completely free of all the delusions, like ignorance, greed, hatred and so on. A bodhisattva at that level is at the same level as an arhat, but they don’t stop there. They have three more bhumis to go to reach full enlightenment. What they do on those last three bhumis is remove another kind of obstacle in the mind, which are called “cognitive obscurations” or “obscurations to omniscience.” There are different terms for these. But those are factors in the mind that prevent the mind from being fully enlightened, fully awakened.

Now, someone who has reached nirvana has not eliminated those. They still have those in their mind, and that’s why their mind is not fully enlightened as a buddha. The bodhisattva wants to remove those, so that’s what they do on the last stages of their path. When the last of those obscurations have been eliminated then they become a buddha. That’s kind of a long answer, but it’s actually quite short because it’s much more complicated than that. [laughter] This is just in a simple way. A bodhisattva does want to eliminate the causes of suffering and the causes of samsara; they do want to eliminate those in their mind. And they do along their path. But then they go further than that. Does that make sense?

Audience: It does. Thank you, Venerable.

Audience: Thank you so much, Venerable. I’ve never heard the fourth truth referred to as attaining realizations. Could you say more about that?

Venerable Sangye Khadro: Well, that’s how it’s explained in our tradition. The word “path” might be different from the Theravada or Pali tradition. In our tradition the word “path” actually means a realization. It means a mental state. It’s not like a physical path obviously that one follows but rather a series of realizations that one attains in one’s mind. And as one attains those realizations, one is moving closer and closer to nirvana or enlightenment. That’s how it’s explained in our tradition. That’s generally the meaning of “the path.” It’s a certain kind of realization. But for the fourth noble truth, true path isn’t just any path but it’s specifically the wisdom that realizes emptiness, the true nature of things. It does include some other realizations as well, but that is the main one. That’s how it’s explained in our tradition.

Audience: Good evening from Scotland, Venerable! Mark Zuckerberg will not like me for asking this, but does scrolling through Facebook constitute gossip if we don’t respond to a post? Or if we do and we answer angrily, does that wipe out any good merit we may have accumulated during the day? Is it better to just not be on social media at all? [laughter] Is there a way to use it skillfully?

Venerable Sangye Khadro: I’m not on any social media. I don’t have time for it. I don’t know how people find time for that. But I remember having a conversation once with some people, and they were definitely people who were learning and practicing the Dharma. They said that you can use social media skillfully if you choose which Facebook sites you get information from, and you can ignore the others. It’s the same with posts: you don’t have to look at every single post that’s on there. You can choose your friends and the people who make posts that are conducive for your spiritual practice, your spiritual growth and so forth. I know there are some Buddhist teachers who use Facebook as a way to teach and connect with their students, so I think that if you have wisdom and a good motivation and you’re skillful at recognizing what is helpful information and what is not, then you can do that. Right now I’m at Sravasti Abbey, and the Abbey has a Facebook account. So, there are people who connect in that way. I think if you are careful in choosing who you connect with—individuals, groups and so forth—then that is possible.

If you do get angry, that is something to be careful about. We do try to watch our mind. But it’s not always possible. Even living here in the monastery with like-minded people, you still sometimes get angry. [laughter] Somebody says or does something that triggers off your anger. But at least in this kind of context, we’re more likely to recognize the anger and recognize that it’s not a skillful state of mind. We’re more likely to work on it and then to try and communicate with the other people that you’re angry at and work out a healthy, positive resolution to the problem. It’s difficult to never get angry. Even if you’re staying all by yourself in a little cabin in the woods and you don’t have any internet or communication with other people, you can get angry at animals and insects and so on. [laughter] You might even get angry at thoughts that come up in your mind when you remember things from the past. As long as we’re ordinary beings, that will still be the case. But at least we have the Dharma, and so if anger does come up in our mind, we notice it and recognize that it’s unskillful and apply an antidote and try not to act it out and create karma. But, it is also helpful to try to avoid situations that you know are going to make you angry if you can help it. [laughter]

The two truths

The next topic, letter C, is the two truths. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has sometimes said that when it comes to people learning Buddhism, for people who were not raised Buddhist, it’s good to start with the four noble truths and the two truths. That’s his recommendation. The four noble truths are not terribly difficult to understand, but the two truths are more challenging. I’m just going to give a brief introduction now, but as we continue through the course, we will come back to this topic of the two truths, and it will become more clear as we go along.

Again, I’m speaking from Mahayana tradition, specifically the Gelug tradition in Tibetan Buddhism. Other traditions might explain these in different ways, so this is one perspective. According to what I’ve learned, all phenomena that exists in the world and in the universe, in samsara and nirvana, is either one of these two truths. So, it’s like a division of phenomena, a way of dividing phenomena into two groups. Whatever exists has to be one or the other. Nothing is both. Nothing can be both of them, but also there’s nothing which is neither of them. There’s nothing that doesn’t fit into these categories. We already came across the term “truths” in the four noble truths, so let me explain what this term means. In Buddhism, a truth is something that exists the way it appears. The way it appears and the way it exists are concordant.

A simple example would be a real rose growing on a rosebush. That is a truth in a way because it looks real and it is real. But on the other hand, there are artificial flowers and sometimes they are so well made that it’s hard to tell if they are real or not. If you’re a little bit far away, you might look at it and think, “Is that a real rose or an artificial one?” You might have to go up and touch it to know. Maybe it’s a false rose, an artificial rose, rather than a real rose. Another example is money. There’s real money, like what a government produces, and they call it a “mint.” So, the United States government produces real dollars. But then there are people who produce counterfeit money. [laughter] So, there are counterfeit dollars, and sometimes they are made so well that it’s difficult to tell at first glance. You may even have to be an expert to tell if it’s a counterfeit bill or a real bill.

That’s the meaning of “truth” as opposed to “falsity.” A truth is something that looks a certain way, and it is that way. A hundred dollar bill that is real and produced by the American government is a true piece of money. And the real rose growing on the bush is a true rose. That’s the general meaning of a truth. And then the opposite of a truth is a falsity. A falsity or something that’s false means there’s discordance between the way it looks and what it is. How it looks and how it appears are not concordant. So, it’s like how the counterfeit hundred dollar bill may look like a real bill, but it’s not. It was not produced by the American government. It was produced by somebody in their basement or whatever. [laughter] That’s a falsity. That’s the meaning of a falsity. It’s not true. It’s false.

Of these two truths, the first one is conventional truth. Within Buddhism, not all Buddhists agree on everything. [laughter] In fact, there are a number of different points-of-view, which isn’t surprising because the Buddha lived and taught more than two thousand five hundred years ago, and then after he passed away, his teachings spread in many different places and were picked up and studied by different people. Over time, different interpretations of Buddhist teachings arose, because some of the Buddha’s words were not easy to understand. They could be interpreted in different ways. So, this is how we have these different schools.

In the Tibetan Gelug tradition, the school that they favor and consider the most correct is called Madhyamaka Prasangika. It traces its teachings to Nagarjuna who lived about four hundred years after the Buddha. He wrote a number of texts, and he was an amazing philosopher. His texts are actually quite difficult to understand, like the Buddha’s were, so they needed further interpretation and clarification. That’s the background of the Madhyamaka Prasangika school. It went from Nagarjuna to other masters down to the present day.

According to this school, the explanation of the two truths starts with ultimate truths. Ultimate truths—and it’s plural rather than singular—are emptinesses of inherent existence. The term “inherent existence” is often used, and there are other terms used that are synonymous with that, such as “true existence,” “objective existence,” and the like. This is a certain mode of existence that appears to us ordinary, unenlightened beings. We see things as if they have this mode of existence: inherent existence or true existence. However, it’s actually not true. [laughter] It’s a false appearance, a mistaken appearance. The reality is that things are actually empty of inherent existence. Inherent existence just isn’t really there although it appears to be there.

The emptiness of inherent existence means the absence, the lack, of that type of existence. Emptiness itself does exist. It is something that exists; it is something that can be known. Aryas are those beings who have realized emptiness. They see emptiness directly. They have a direct, non-conceptual realization of emptiness, so they can see the emptinesses of things. The reason it’s plural—emptinesses rather than just emptiness—is because every single phenomena, everything that exists, has its own emptiness, has emptiness as a kind of quality. Emptiness is a quality of it, so each thing has its own emptiness. So, we talk about the emptiness of my cup, for example, or the emptiness of a table, or the emptiness of our body, or the emptiness of our mind, or the emptiness of our own self: who we are, what we are. Everything has emptiness as its true way of existing, it’s actual way of existing. That’s the meaning of ultimate truth according to this school, the Prasangika.

Emptiness in different traditions

Ultimate truths are the emptinesses of inherent existence of all phenomena. I have in parentheses there that another term for emptiness is selflessness. That term is also used in the text and in the teachings. We’ll use it again later. So, emptiness and selflessness are interchangeable. You do have to be a bit careful with these terms. Even the term emptiness doesn’t always have the same meaning for different schools. For example, one of the schools is called the Chittamatra or the “mind only school,” and they use the term emptiness. The school is still very popular in Eastern Asia, Japan, Korea and the like. That school also talks about emptiness; they also have the term emptiness. But when you investigate what they mean by emptiness, it’s not the same as Madhyamaka Prasangika’s idea of emptiness.

Also, the Madhyamaka, the Middle Way School, has two divisions. The first one is called Madhyamaka Svatantrika, the translation is “Middle Way Autonomous.” And then there’s Madhyamaka Prasangika, “Middle Way Consequentialists.” I’ve been talking about the second one, Madhyamaka Prasangika. But the first one, Madhyamaka Svatantrika, also uses the term emptiness. But again, it’s a little different. It’s not exactly the same as Prasangika. I’m just saying this as a warning because you might read different books and encounter the term emptiness, but don’t assume every time you encounter that word that it’s talking about the same thing. You have to investigate. [laughter] Buddhism is complicated.

Ultimate truths are emptinesses. This means the emptiness of inherent or true existence: a false mode of existence. You’re probably wondering “what does that mean?” We’ll get to that. That’s coming. [laughter] That’s what this course is all about. Then conventional truths is everything else. Everything else that isn’t an emptiness is a conventional truth. That includes bodies, minds, beings, cars, phones, buildings, trees and so forth. All phenomena other than emptinesses are conventional truths. Even though we use the term “conventional truth,” actually they’re not truths. [laughter] They are not truths but rather falsitities. Remember, the meaning of a falsity is something that has some discordance between how it appears and how it exists. For example, let’s just say a car. That’s a conventional truth. When we ordinary beings see a car, it appears inherently existing, truly existing. It appears to exist in that way. But in fact, it doesn’t. It’s not inherently existing. It’s empty. The real nature of a car is empty of inherent existence. So, there’s some discordance between the way it appears and the way it actually exists.

This is a difficult point, so don’t worry if you don’t understand it. It’s just a bit of an interesting point that a car is called a conventional truth because it’s empty of inherent existence, but actually it’s not a truth because it doesn’t exist as it appears. There’s a discrepancy between the way it exists and the way it appears. The topic of the two truths is not easy. It’s also complicated because each of the four Buddhist schools views emptiness differently. The first is called the Vaibhasika, the “Great Exposition School,” and the second is Sautrantika, the “Sutra School.” Those are called Hinayana schools. The teachings they give are primarily directed to the attainment of nirvana or liberation. The other two schools are Mahayana and Chittamatra Madhyamaka, and those are mainly aiming for full enlightenment or buddhahood. If you are interested in this topic, this is a really good book. It’s called Appearance and Reality, and the author is Guy Newland. He’s a professor who has a PhD from the University of Virginia. He’s a student of Jeffrey Hopkins, and he’s very knowledgeable.

He actually wrote a bigger book called The Two Truths, which is primarily about the Madhyamaka Prasangika’s version of the two truths. This other book, though, is relatively small. It’s only about a hundred pages. He goes through the four schools and explains how each of them explains the two truths. I wouldn’t say it’s easy to read this book, but it’s relatively easy because he’s one of us. [laughter] He’s an American, and so he’s using ordinary language, and he’s also kind of having questions of the same kind that we would have about this topic. And he did talk with teachers to get answers to his questions, so it’s kind of a relatively easy, accessible book to learn more about the four schools and in particular how they explain the two truths: conventional truths and ultimate truths. We don’t have time to go into all of that, but for those who are interested, that’s a good text you could explore.

Background on emptiness

There’s a lot of explanation one can do regarding this topic of emptiness. It’s vast and deep and detailed. So, we will come back to the two truths a bit later. I would like to move on now to giving some background on the topic of emptiness. I guess I already talked about this, but just to reemphasize this, why is it important to learn about and meditate on emptiness? The realization of emptiness is the main antidote to ignorance. In fact, it’s the only one. [laughter] It’s the only thing that’s going to work to get rid of ignorance. Even if we develop love and compassion and bodhicitta, and we have these wonderful feelings for sentient beings and want to help them, that will not eliminate our ignorance. It’s only the understanding of emptiness, the wisdom realizing emptiness, that is able to eliminate ignorance. And why we want to eliminate ignorance is that it’s the root of all our problems. It’s the root of samsara.

Our ignorance about the true nature of things is what keeps us stuck in samsara, in cyclic existence, with all of this suffering and problems. So, if we want to get out, we have to overcome ignorance. The last bullet point says, “Without the realization of emptiness it is not possible to obtain liberation or enlightenment.” Whether one wants to attain nirvana, liberation from samsara, or one wants to go all the way to full enlightenment, buddhahood, you can’t do that without the realization of emptiness. That’s why it’s so important.

Background on the teachings

Now the lineage, the background of the teachings on emptiness, started with the Buddha, specifically what are called the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras or the Prajnaparamita. There are a number of these. They were taught by the Buddha, and some of them are really long. The longest one is 100,000 verses. It hasn’t been translated into English, and in the Tibetan form, it’s a very thick book. But then there are shorter ones, and you’re probably familiar with the Heart Sutra. That’s a sutra that is recited in all the Mahayana traditions: Korean, Chinese, Japanese and so on. That is an example of a Perfection of Wisdom sutra.

The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras have two meanings, two main topics you might say. The next bullet point says, “There are two levels of meaning in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras. The first one is explicit,” meaning this is mainly what the Buddha is talking about in an overt or explicit way. He’s talking about wisdom, specifically the wisdom that understands emptiness. That’s the main topic explained in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras. Those teachings were passed from Manjushri to Nagarjuna and so forth. Nagarjuna lived about four hundred years after the Buddha, and he had access to the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras. He studied them and wrote commentaries to them. He also had this connection with Manjushri, the Buddha of wisdom. I presume he had visions of Manjushri and received help and guidance from Majushri. That’s kind of the lineage of these teachings on emptiness.

Number two says “implicit,” meaning when the Buddha was giving these Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, mainly he was talking about emptiness, but a less obvious meaning was about method. It’s about the method side of the path, which includes things like compassion, love, bodhicitta, the six perfections. It’s that side of the path which is more about the bodhisattva cultivating these positive altruistic attitudes and working for the benefit of sentient beings and following the path to enlightenment. That’s explained in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras in a less obvious way. The lineage of those teachings were passed from Maitreya. Maitreyea is also a buddha, and in fact he is the Buddha who will come next, in the future. I’m not sure exactly what year, but at some point in the future, Maitreya will come into the world and again teach the Dharma. But Maitreya is already existing in some pure land, and he had a human disciple named Asanga who lived maybe a thousand or twelve hundred years ago. Asanga is the person who received these teachings on the method side of the path, and then he passed them on. So, there are these two lineages, the wisdom and method lineages. They were passed from teacher to disciple up to the present day.

They’re still very much alive and being taught and practiced today. These two lineages also are two sides of the path that we need to develop if we want to reach enlightenment. You’ve probably heard this analogy of method, the compassion side of the path, and wisdom being like two wings of a bird. Just as a bird needs two wings in order to fly, if we want to go to enlightenment, we need both of these wings of method and wisdom. If we only have wisdom but we lack compassion and love and bodhicitta, we won’t be able to go all the way to enlightenment. We can go to nirvana. We can reach nirvana with wisdom alone, but not full enlightenment. We do need the compassion, the bodhicitta, side of the path. But if we only have that side of the path without wisdom, we also won’t be able to go all the way to full enlightenment. We do need to realize the true nature of things to overcome ignorance.

So, there are these two lineages of the teachings and two aspects of the path that we need to develop. These two lineages were both brought to Tibet by great masters. Some of the masters who brought Buddhism to Tibet were Santaraksita, Kamalasila, Atisha and so on. And then these teachings were disseminated in Tibet and passed on from teacher to disciple. In the Gelug tradition, Lama Tsongkhapa was the founder of this tradition, and he received these teachings and then continued to disseminate them. Eventually, they came down to our own spiritual teachers. I don’t know if this is interesting for you or not, but it is good to know where these teachings on emptiness came from. They weren’t just invented by Tibetans. [laughter] They weren’t just invented by our current lamas. They can be traced all the way to the Buddha.

Meditation on emptiness

We’ve only got about ten minutes left, and the next topic is going into more depth on the topic of emptiness. So, let’s do a little bit of meditation. There’s been quite a bit of information that you’ve heard this morning, so let’s do some meditation and see if we can absorb and digest some of this information. Make yourself comfortable and try to keep your back straight. That helps the mind to be more clear and focused. But still be relaxed as much as possible. Then let your mind settle down into your body. Be aware of your body, your posture. Be aware of your breathing, flowing in and flowing out.

Then let’s contemplate some of the main points we have covered in this class. We started off by looking at the four noble truths. The first two truths explain our situation as ordinary, unenlightened beings. We have suffering, problems, difficulties, and we’re not alone. The eight or so billion people, and other beings as well like animals, all of us experience duhkha: different kinds of suffering, unsatisfactory experiences. See if that makes sense to you. See if you’re able to accept that.

When contemplating duhkha, we need to do it in a balanced way. We need to be aware of it, not deny it. But we also need to remain positive and optimistic and not feel overwhelmed and in despair. It does exist, but it’s not something permanent that will be there forever and ever and ever. There is an end to duhkha. The Buddha explained that in order to bring about the end to duhkha, we need to look at its causes. Where does duhkha come from? What causes it? In his experience, what he realized, is that it’s caused by mainly factors in our own mind. We can call these delusions or afflictive emotions. The Sanskrit term is klesha. These are aspects of our mind that are mistaken, that see things incorrectly. And the meaning of them is negative as well; for example, anger and hatred can lead us to do harmful things. Also, greed and attachment can lead us to do harmful things, like depriving others of their possessions or cheating and manipulating them so that we get more of the things we want. These mental afflictions or delusions are the main cause of suffering. Think about that and see if that makes sense to you.

It’s not too difficult to see how these afflictive emotions cause suffering right away. They make our own minds disturbed, and if we get caught up in them and act them out, then we do things that can cause suffering to others. But they also cause suffering in a more long-term way. When we do actions motivated by delusions then we plant karmic seeds in our mind. And then later, maybe in this life or future lives, those seeds become the cause for more suffering and continuing to take birth in samsara, cyclic existence. The main cause of all of this is ignorance of the true nature of things, ignorance of how things actually exist—our own “I” or self, others and everything around us. We see these in mistaken ways. We’re ignorant of the real way things exist, and that’s why we act in such deluded ways, creating suffering for ourselves and others.

Fortunately, there is a solution. Ignorance is not something permanent in our mind. It’s just a factor in our minds that can be eliminated. And all the other afflictive emotions can also be eliminated such that they will never arise again. That’s the meaning of the third truth, true cessations. And the way to do that is by developing the wisdom that understands the true nature of things, what we call “emptiness” in our tradition. Wisdom of emptiness completely eliminates ignorance and all the other afflictive emotions, and then we stop creating the karma that leads to further suffering in the future. We are really fortunate that we have the opportunity to learn these teachings because if we can develop this wisdom in our minds, we can free ourselves from suffering,and we can also develop our potential for full enlightenment, buddhahood, at which time we can help others to be free of suffering and help them to reach enlightenment. See if that sounds like something inviting, something you would like to do.

Dedicating the merit

Let’s conclude by dedicating the merit, the positive energy, we have accumulated by following this class with a good motivation. It’s said that any effort we make to learn about emptiness, even if we feel like we don’t understand it, is so beneficial. We definitely create merit, positive energy, and the best thing to do with that positive energy is to share it with others.

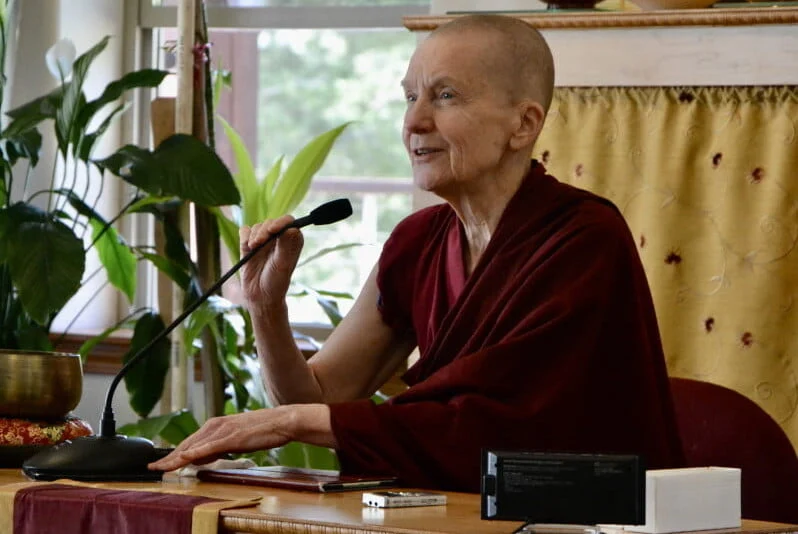

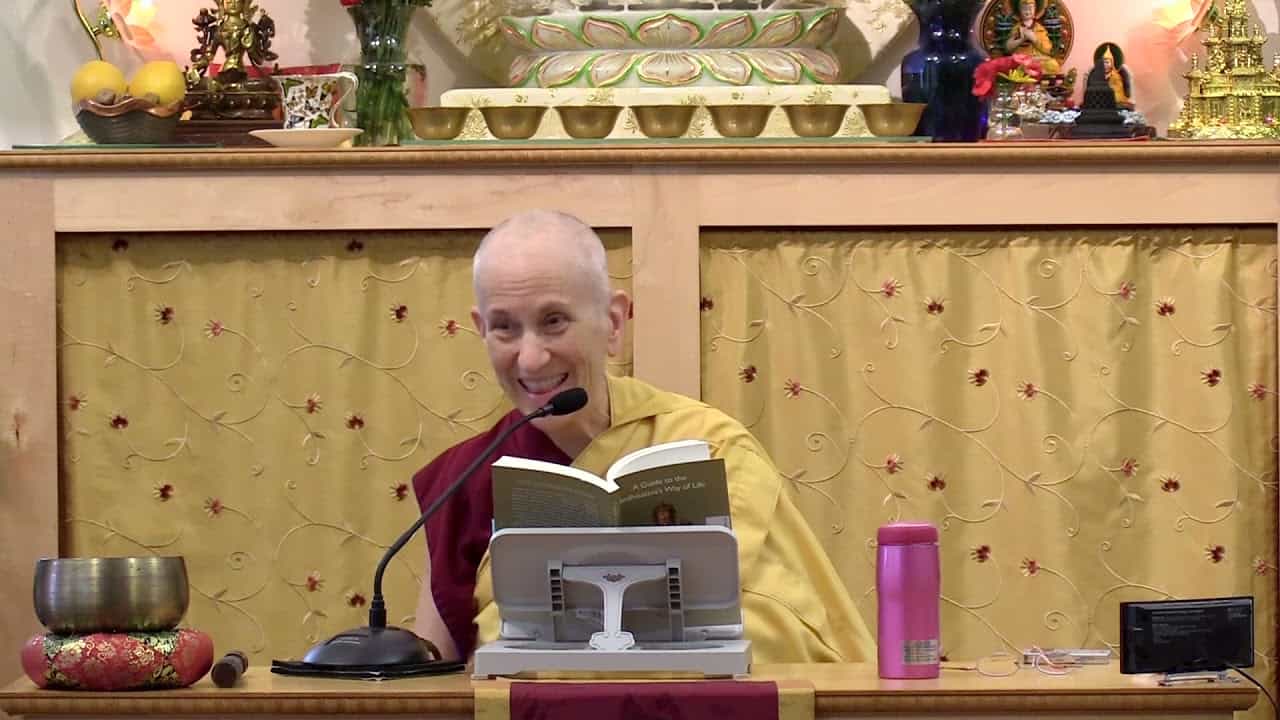

Venerable Sangye Khadro

California-born, Venerable Sangye Khadro ordained as a Buddhist nun at Kopan Monastery in 1974, and is a longtime friend and colleague of Abbey founder Ven. Thubten Chodron. Ven. Sangye Khadro took the full (bhikshuni) ordination in 1988. While studying at Nalanda Monastery in France in the 1980s, she helped to start the Dorje Pamo Nunnery, along with Venerable Chodron. Venerable Sangye Khadro has studied Buddhism with many great masters including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, and Khensur Jampa Tegchok. She began teaching in 1979 and was a resident teacher at Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore for 11 years. She has been resident teacher at the FPMT centre in Denmark since 2016, and from 2008-2015, she followed the Masters Program at the Lama Tsong Khapa Institute in Italy. Venerable Sangye Khadro has authored several books, including the best-selling How to Meditate, now in its 17th printing, which has been translated into eight languages. She has taught at Sravasti Abbey since 2017 and is now a full-time resident.