End-of-life care

End-of-life care

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, many children, spouses, partners, siblings, or friends have been faced with end-of-life care decisions for their loved ones. Of course, making these kinds of decisions has been going on in one form or another since human beings appeared on this Earth, but with over 30 million cases in the US and 550,000 deaths in the last year due to COVID-19, end-of-life decisions are impacting more people. Yesterday, on March 28, 2021, there were 500,419 new cases of COVID-19 worldwide and 6,585 deaths yesterday. This pandemic is not yet close to being contained.

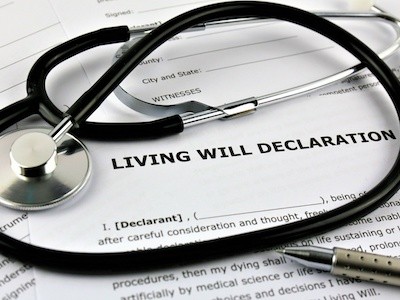

How can we approach the difficult process of making end-of-life care decisions regarding loved ones? First, if all of us would fill out advance care directives, our loved ones would be spared a lot of pain and anxiety when our death is approaching. Advance care planning involves learning about the types of decisions that might need to be made, considering those decisions ahead of time, and then letting others know about your preferences. These preferences then are often put into an advance directive—a legal document that goes into effect only if you are incapacitated and unable to speak for yourself.

It is a kindness to others and is so helpful for them to know what type of medical care you want. An advance directive also allows you to express your values and desires related to end-of-life care. Of course we do not know when we will die, but we all know that we will die at some point. Being prepared for the transition has a calming effect on our minds.

An advance directive is a living document—one that can be adjusted as your situation changes over time due to changing health status or new information or treatments. When people have filled out and signed an advance directive, this becomes a legally binding document that drives the medical care of the person. Advance directives include decisions about the use of emergency treatments to keep you alive. Medical technology now contains several artificial or mechanical ways to keep a person breathing and their heart beating. Decisions that may come up at this time relate to such things as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ventilator use, artificial nutrition, and hydration, among others.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) might restore your heartbeat if your heart stops or is in a life-threatening abnormal rhythm. It involves repeatedly pushing on the chest with force, while putting air into the lungs. This force has to be quite strong, and sometimes ribs are broken or a lung collapses. Electric shocks, known as defibrillation, and medicines might also be used as part of the process. The heart of a young, otherwise healthy person might resume beating normally after CPR, but CPR often is not successful in older adults who have multiple chronic illnesses or who are already frail.

Ventilators are machines that help you breathe. When a ventilator is used as an emergency treatment, a tube connected to the ventilator is put through the throat into the trachea (windpipe) so the machine can force air into the lungs. Putting the tube down the throat is called intubation. Because the tube is uncomfortable, medicines are often used to keep the person sedated while on a ventilator.

If you are not able to eat, you may be fed through a feeding tube that is threaded through the nose down to your stomach. If tube feeding is still needed for an extended period, a feeding tube may be surgically inserted directly into your stomach.

If you are not able to drink, you may be provided with IV fluids. These are delivered through a thin plastic tube inserted into a vein.

Artificial nutrition and hydration can be helpful if you are recovering from an illness. However, studies have shown that artificial nutrition toward the end of life does not meaningfully prolong life. Artificial nutrition and hydration may also be harmful if the dying body cannot use the nutrition properly.

The other option is comfort care. Comfort care is anything that can be done to soothe you and relieve suffering while staying in line with your wishes. Comfort care includes managing shortness of breath, limiting medical testing, providing spiritual and emotional counseling, and giving medication for symptoms experienced.

Often our family members aren’t so keen on talking about death or what they want for medical and spiritual care when they are very ill or approaching death, so the decisions are left to the family when the person can no longer communicate their wishes. This may be uncomfortable for the family members because they don’t know what their loved one wants. Sometimes the dying person may have said communicated one preference to one family member and another preference to another family member, but since an advance directive was not made, the family does not know their loved one’s most recent wish.

So how can we approach this from a Buddhist perspective to help our family members or others who ask for guidance? The Buddhist practice of recognizing impermanence is important. Awareness of impermanence enables us to work with attachment to people and things. Grounding ourselves in our Buddhist practice before we make health-care decisions will go a long way to help us make balanced decisions.

First of all, making care decisions with a motivation of love and compassion is never wrong. There are no right or wrong decisions as long as we discuss the situation with the care team and family or trusted friends. In this age of technology, the simple process that death once was has been replaced with many options to extend life for some time, so discussion with the medical team, friends and relatives, and our spiritual teachers is very helpful. Reach out for help when you need it.

If there is no advance directive, then family members can get together and decide what kind of treatment they think their loved one would want if they were able to communicate. This is not an easy task but if it is a group decision, it is easier. If there aren’t other family members, then reaching out to trusted friends and spiritual advisors to talk about what you are facing can be very helpful. Others cannot make the decisions for you but can be loving sounding boards so you can get clear about what decisions to make. The other resource is of course the health-care team. Tell them you want all the information, you want them to be straightforward and honest about the prognosis and alternative types of care. Asking many questions of the health-care team can clarify the situation. For example, you might ask, What is the chance of your loved one surviving the illness? What is the quality of life if certain treatments are given?

From a Buddhist perspective, when our loved ones are near the end of their life the best circumstance for them to have a fortunate rebirth is for them to be in a calm and loving environment, free from anxiety and chaos.

Karma dictates our lifespan. In my career I have cared for patients with very minor illness that died, and I have cared for patients with catastrophic illnesses that don’t die but from a medical standpoint should have. Because of our attachment, we often get caught up in the latest technology that may prolong life. But when our karma runs out, we die. With technology the body can be kept breathing and the heart beating. Is the person’s consciousness still present? We don’t know.

When I have made these decisions for my family members, I discussed the options with other family members and then decided in a way so that 10 years from now I would remember it was a group decision with the motivation of honoring the family member with love and compassion. When my mother was diagnosed with cancer I sat down with her and helped her fill out an advance directive called Five Wishes. It covers care decisions as well as after-death arrangements. I wasn’t sure she would participate in this, but to my surprise she did wholeheartedly. It was one of the most tender, honest conversations we had ever had.

It is helpful to keep in mind that whatever decisions we make, in the end the person will eventually transition to the next life. So, we hold the decisions lightly, as a dependent arising. There are more causes and conditions for what is happening they we can ever know. There is so much in life that is beyond our control. So rest in the motivation of love and compassion and then there will be no regrets.

Venerable Thubten Jigme

Venerable Jigme met Venerable Chodron in 1998 at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center. She took refuge in 1999 and attended Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle. She moved to the Abbey in 2008 and took sramanerika and sikasamana vows with Venerable Chodron as her preceptor in March 2009. She received bhikshuni ordination at Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan in 2011. Before moving to Sravasti Abbey, Venerable Jigme (then Dianne Pratt) worked as a Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner in private practice in Seattle. In her career as a nurse, she worked in hospitals, clinics and educational settings. At the Abbey, Ven. Jigme is the Guest Master, manages the prison outreach program and oversees the video program.