The 22nd Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering

Every year for twenty-two years, Western Buddhist monastics have been meeting for a five-day gathering to learn about each other’s teachings and practices and to discuss topics of common interest. This year forty of us met at Land of Medicine Buddha in Soquel, California, October 17-21, our topic this year being Sustaining the Sangha in the West. Most of our sessions began with a presentation, followed by discussion. Sometimes our discussions were in dyads or small groups, other times with the entire group. The gathering follows the traditional meaning of the word “sangha” as a community of four or more fully-ordained monastics.

Participants at the 22nd Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering. (Photo courtesy of Land of Medicine Buddha)

In meeting together in harmony and learning about each other’s practices, Western monastics are doing what our Asian forebearers could not due to their speaking different languages and lacking modern transportation—we are discarding misconceptions about one another’s traditions, cultivating genuine respect for each other, and sharing ideas to spread the Dharma. We are experiencing our unity as the Buddha’s followers while acknowledging our differences.

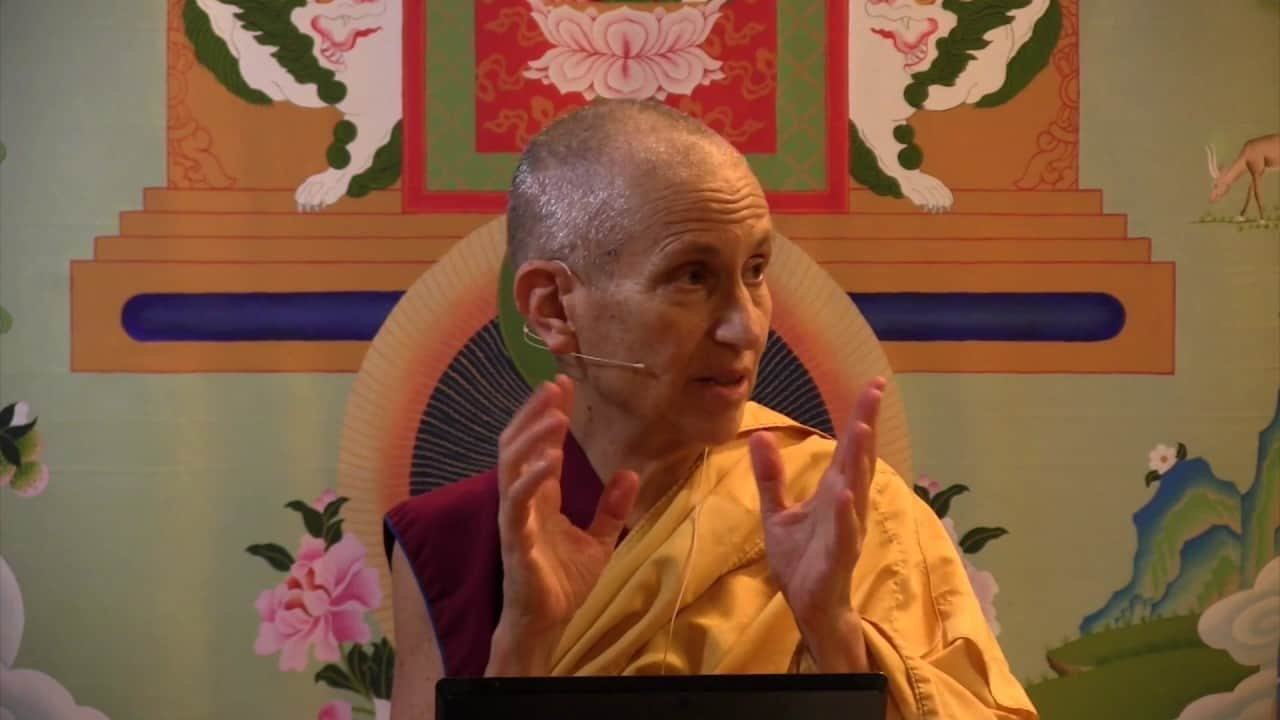

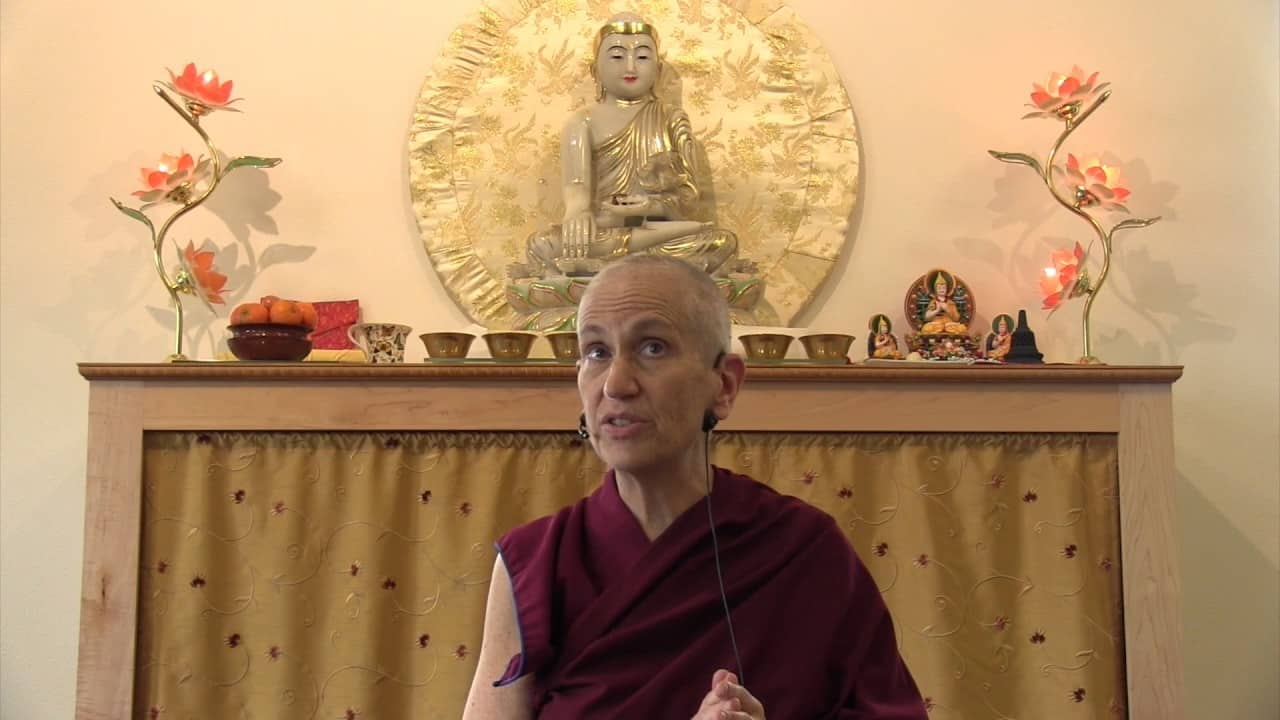

Tuesday morning, Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron, author, teacher, and abbess of Sravasti Abbey, gave the opening talk. She began by honoring the assembly, saying that the future of Buddhism in the West to a great extent depends on the sangha, who for centuries have been tasked with learning, practicing, and teaching the Dharma and the Vinaya (monastic discipline) to future generations. When monastics live in community, they can do so much more than they can individually; the accumulated virtue of a group of monastics attracts great masters to give teachings there and inspires lay Buddhists to practice earnestly. Sangha members need to balance three elements: studying and teaching the Dharma, practicing and meditating on it, and serving others. Each person and each community will balance these differently and we can rejoice at all the virtue that others create, knowing that as one individual we can’t do everything in one lifetime. Rejoicing at the practice of all Buddhists of all traditions brings us closer together as one large Buddhist community that transcends sectarian differences. The sangha needs to maintain the teachings of the various Buddhist traditions and clearly differentiate between the Dharma and culture.

Tuesday afternoon, Bhikkhuni Tathālokā Therī, a bhikkhunī preceptor and founder of the Dhammadharini community in Northern California, began by sharing ancient Pāli verses from the Buddhist canon on the excellent qualities of the Sangha. She then spoke on “Monastic Sustainability in the West” in light of the big time frames in Buddhism—this year being (according to traditional Theravada Buddhist counting), the 2600-year Anniversary of both the founding of the Bhikkhuni Sangha and fulfillment of the Buddha’s intention to found a fourfold assembly. She shared the experiences of her monastic community living entirely on dana (offerings given with a generous intention), and the surprising support and participation there is in monastic alms rounds that involve people who might never come to an indoor meditation session or Dharma teaching. She also spoke on “Moral Awakening in the Land” and the rising tide of a new and contemporary valuing of moral integrity in the United States. Finally, she answered question at length on the application of our deepest hearts’ intentions to contemporary circumstances via the applied training and practice of the Buddhist teachings on mindfulness (sati) and clear awareness (sampajañña).

On Wednesday morning, Venerable Haemin Sunim presented elements of his dissertation research which involves planning a training program for Western Buddhist monastics from all Buddhist traditions. The program revolves around knowledge, ethics, and compassion. Knowledge is primarily learning the Buddha’s teachings and the practices of one’s tradition, but also includes practical areas of knowledge such as temple management, basic psychology, and counseling skills. Although monastics have traditional training in ethics, the numerous problems we have seen among Buddhist teachers engaging in inappropriate relationships with their students necessitates a careful investigation of this phenomenon and ways to avoid it. In addition, the ethical sphere will include training in inclusiveness in an effort to diversify our communities and to engage our communities in creating positive change in regard to privilege and oppression in society in general. Compassion includes both the inner cultivation of a compassionate mind and compassionate action in the world through the completion of an extensive service project in which students meet the suffering of the world head on. All of us were very interested in this project and contributed our feedback to help it be successful.

Khenmo Drolma, founder of Vajra Dakini Nunnery in Maine, also gave a presentation on Wednesday morning about creativity, the process of opening our minds and manifesting thought and visions into tangible form as a training in generating wisdom. Khenmo Drolma addressed this topic in regards to both teaching others and enriching monastic lives. People learn with all their senses, absorbing concepts visually, kinesthetically, as well as linguistically. Khenmo Drolma illuminated the importance of creatively addressing all learning styles when teaching. Noting the integration of the arts in the Tibetan system, and that the education of monastics includes sacred music, dance, and sculpture, she advocated that this sensibility become a part of Western Dharma training. She also traced for us her process of creating a 32’ tall statue of Songtsen Gampo, the king who first welcomed Buddhism to Tibet. This magnificent statue was set in the courtyard of a Tibetan Buddhist Library in Dehradun, India.

Wednesday afternoon we visited Pema Osel Ling, a Nyingma center near Watsonville, where deep in a madrone forest we came upon a huge stupa for Dorje Drollo, a wrathful manifestation of Padmasambhava, surrounded by the tradition eight stupas. Lama Sonam gave us a helpful explanation and the residents offered tea and treats in their large prayer hall, which held an enormous statue of Guru Padmasambhava as well as inspiring paintings and photos of their lamas.

Bhiksu Steve Carlier, a translator and teacher, gave the morning presentation on Thursday, discussing what he saw as an important but neglected and difficult-to-discuss aspect of sangha life: having and showing respect for Western sangha members. This concerned not only people often showing respect for all Tibetans and not valuing Western practitioners, but also within the Western sangha, the difficulty that junior and senior monastics have in respecting each other. The Vinaya instructs junior members to respect seniors, but it does not say that seniors can demand respect from juniors. In fact, the Buddha set up a system of care for each other, with seniors guiding, advising, and encouraging juniors and juniors aiding seniors with daily tasks and errands. Venerable Steve also shared his thoughts on Buddhists’ attitudes towards women and gays and lesbians and based on scriptural analysis, he advocated for gender equality and acceptance of sexual orientation.

Rev. Jisho Perry, a senior monastic from Shasta Abbey, spoke about making sure we focus on deepening our practice. We should make strong aspirations to return in the next life to continue our training in order to realize bodhicitta and progress to full awakening. He also encouraged us to creative skillful means to teach the Dharma, especially to young people and children, and to find joy in our Dharma practice and manifest that joy skillfully. He gave practical examples such as Rev. Master Jiyu Kennett’s “enlightenment board game” and young children playing the hordes of Mara while they took turns sitting quietly like the Buddha. To help spread the Dharma, we need to be willing to take disciples and to ordain and train them. In addition, we need to have the courage and vision to found monasteries, temples, and religious communities. Developing educational and learning opportunities for young monastics is also part of that process. In short, rather than leave the future of Buddhism in the West to others, as sangha we must be active in teaching the Dharma, guiding students, and creating places for them to study and practice.

Friday morning we had discussion groups focused on the topics from the previous days. Then, to conclude the 22nd Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering, we one-by-one expressed our dedication of merit. Listening to everyone’s inspiring dedication for specific aims that were dear to their hearts bonded us together and instilled in us the aspiration to personally bring these aims about.

Report written by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.