Overview of the stages of the path

Part of a series of teachings on The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, a lamrim text by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the first Panchen Lama.

- Overview of the stages of the path to awakening

- How the three scopes of practitioners relate to the three principal aspects of the path

- The motivation and practices of each scope

Easy Path 04: Lamrim overview (download)

I want to say hello to everybody, good evening to some people, and I think good morning to some others, depending on where you are. For our friends in Singapore listening it’s Saturday morning. Venerable Chodron wanted me to let you know that she couldn’t be here because her father passed away, and so she hopes to be back next week. We’re pretty sure she will be. And she’s doing okay, but sorry that she couldn’t make it.

She asked me to give a little overview of the lamrim, the gradual path to awakening, and especially related to the three principal aspects of the path—so that’s basically the complete path to full awakening from beginning to end in one hour. [Laughter] We will give it our best. Let’s start first by doing a little bit of silence, and then I’ll set up a very simple visualization and we’ll do the recitations, then we’ll have some silent meditation and I’ll set the motivation. So let’s start with a minute of silence just to bring ourselves from what we were doing before to what we’re doing now.

[Silent meditation]

Guided meditation and abbreviated recitations

Visualize in the space in front of you, made of radiant transparent light, the divine form of Shakyamuni Buddha, golden in color, sitting on a throne, with snow lions, sun and moon disc.

Around the Buddha are all the holy beings: Manjushri is on his left, Maitreya is on his right, Vajradhara is behind him, around him are all of the various buddhas of different types of tantra and around those are all the thousand buddhas of this eon. Around them are all the bodhisattvas and then the different kinds of arhats, the hearers and the solitary realizers, around them are all the dakas and dakinis, so in this great space in front of us are all these holy beings, and our spiritual mentors are in front of the Buddha. The Dharma texts are on beautiful tables, and the sounds of the Dharma are filling the air. Around us we imagine all sentient beings. We’ll start with the recitations:

I take refuge until I have awakened in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. By the merit I create by engaging in generosity and the other far-reaching practices may I attain Buddhahood in order to benefit all sentient beings. (3X)

Then we’ll recite the four immeasurables:

May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes.

May all sentient beings be free of suffering and its causes.

May all sentient beings not be separated from sorrowless bliss.

May all sentient beings abide in equanimity, free of bias, attachment and anger.

As we recite the seven-limb prayer, visualize yourself doing these activities of each verse:

Reverently I prostrate with my body, speech and mind,

And present clouds of every type of offering, actual and mentally transformed.

I confess all my destructive actions accumulated since beginningless time,

And rejoice in the virtues of all holy and ordinary beings.

Please remain until cyclic existence ends

And turn the Wheel of Dharma for sentient beings.

I dedicate all the virtues of myself and others to the great awakening.

When we offer the mandala you want to visualize everything beautiful in the universe. You want to offer this with the wish to receive Dharma teachings and to generate realizations within your mindstream. So visualize offerings filling the sky and offer these to the Buddha and all the holy beings—and take great delight in making this offering; multiply it hundreds and hundreds of times.

This ground anointed with perfume, flowers strewn,

Mount Meru, four lands, sun and moon;

Imagined as a Buddha land and offered to you,

May all beings enjoy this pure land.The objects of attachment, aversion and ignorance, friends, enemies and strangers, my body, wealth and enjoyments – I offer these without any sense of loss. Please accept them with pleasure and inspire me and others to be free from the three poisonous attitudes.

Idam guru ratna mandala kam nirya tayami

All these offerings melt into light and dissolve into the Buddha, and he accepts them with pleasure, and then he radiates light back into you, and this light inspires us to complete the gradual path to awakening.

Now imagine that a replica of your teacher in the aspect of Shakyamuni Buddha comes to the crown of your head as we make this request. This Buddha on the crown of your head is acting as your advocate as we make this request to all of the holy beings and the lineage holders.

Glorious and precious root guru,

Sit upon a lotus and moon seat on my crown.

Guiding me with your great kindness

Bestow upon me the attainments of your body, speech and mind.The eyes through whom the vast scriptures are seen,

Supreme doors for the fortunate who would cross over to spiritual freedom,

Illuminators whose wise means vibrate with compassion –

To the entire line of spiritual masters I make request.

Then we’ll say the mantra and imagine this light flowing from the Buddha on the crown of your head into you—white light purifying you, and then you can also imagine golden light bringing in realizations.

Tayata om muni muni maha muniye soha (7X)

Now sit silently and do breathing meditation. [Silent meditation]

Motivation

As we listen to these teachings, let’s have the motivation to really make the determination to follow this path. As we get to hear about all the different aspects of the path—and we’ll be going through rather quickly, of course—we can still carry with us all the way through this teaching this wish to be of benefit to others by becoming a Buddha. Let’s expand our minds and consider the possibility of what we’re doing tonight being one step further along that path—especially with this topic which has so many benefits. So you can slowly come out of your meditation.

Benefits of the lamrim

I’m very happy to give this talk because it’s very helpful for me to study the lamrim. In the teachings of the lamrim they talk about the benefits of studying it. So I want to introduce this topic with a story I heard from Venerable Chodron about these two Tibetan Kadampa geshes. Way back when one geshe asked his disciple, “Would you rather be a master—really knowledgeable, and proficient in all those sciences, and have single-pointed concentration, and have clairvoyance? Or would you rather be a person who’s heard Lama Atisha’s teachings, these lamrim teachings, yet hasn’t realized them but has a firm recognition of their truth?”

Actually what you’re doing is here is saying “Do you want to be somebody who has all these worldly skills or to be somebody who doesn’t even have any realizations?” Whereas the first one even had realizations of single-pointed concentration and clairvoyance…or, “Would you rather have just this recognition of the truth of the full path?” The disciple said, “I’d rather be someone who actually has this firm recognition of the truth.” And why would he say that—especially when these kind of accomplishments are so valued, both spiritually and otherwise? Worldly and spiritually we value single-pointed concentration and all this knowledge of the world and sciences. The reason he choose as he did is because, actually, that kind of worldly knowledge and even single-pointed concentration—when you die, it’s gone. It alone is not going to actually help you in that it doesn’t liberate us.

This disciple really had the awareness that death comes so suddenly, we just never know. And all of these good qualities would end; and negative karma could ripen and just throw him into any kind of rebirth in the future. So there’s no security. Because those worldly qualities don’t have a lasting impact on the mind, he understood that it was important to train in the Buddha’s teachings, and plant these seeds that we can carry with us into the future—that eventually will lead to realizations of liberation and enlightenment. He also might have known that having clairvoyant powers alone isn’t really necessarily beneficial, because if you don’t have ethics along with it you can actually do a lot of damage. He clearly knew it was more important to train in the gradual path.

Four greatnesses of the teachings

When you read Lama Tsongkhapa’s Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path you’ll find that one of the earlier chapters talks about the greatness of the teachings. Our teachers tell us these things so that we’ll have more respect for the teaching, and the first thing they talk about are the qualities that come to students who study this. This is one of things that motivates me in actually giving this talk, because I’ve seen the truth of this in my own experience of practicing the Dharma.

The four qualities are listed for a student. The first is that you will know that all the teachings are free of contradiction. The second is you will come to understand all the teachings as instructions for practice. The third is you will easily find the Buddha’s intent in giving teachings. Then the fourth is you will automatically refrain from great wrongdoing.

1. All the teachings are free of contradiction

First, knowing that teachings are free of contradiction: When you first meet the Dharma, and if you don’t have this kind of presentation of the gradual stages of the path, it’s hard to figure out what to do. It’s hard to understand all these various practices and how they all fit together.

2. All the teachings as instructions for practice

In the context of the lamrim, with its root text that Atisha wrote called The Lamp to the Path to Enlightenment, what does this mean that the teachings are free of contradiction? It means that one person practices all of these teachings in order to become a Buddha. And why is that? It’s because the lamrim has gathered up all of the key points from both the sutra and the mantra vehicles—both the sutra teachings and the Vajrayana teachings. Some of these topics are main points and some of them are side branches; but Atisha basically gathered all of that together and put it in an order. This is what we’ll speak about tonight. And so in that way they’re free of contradiction.

Also we come to understand that everything that the Buddha taught, all of these scriptures, are actually instructions for practice. That’s a very important point and Lama Tsongkhapa wrote about this too. We see this all the time here when people don’t get that point. For example, when people don’t understand this then they think there are like two separate forms presented: there are all these great classic texts and then there’s what someone teaches you in person. And then people sometimes really don’t know how to practice, because they think that whatever they’ve studied— “Well, that’s not what I practice, so then what do I do?” One of Atisha’s students was meditating on Atisha’s instructions, and he said something that really explains this very clearly. He said he understands all of the texts as instructions for practice, and they “grind into dust all of the wrong actions of our body, speech, and mind.” Regarding this Lama Tsongkhapa says that this is the understanding that we need to have—that all of the teachings are for practice, and all of the practices are to help us get rid of all our wrongdoings and generate all of the realizations of the path.

The person who carried on Atisha’s teachings was Dromtonpa. He said that it’s a mistake after hearing all these teachings and studying all these teachings if you feel like you need to look elsewhere to figure out how to practice. Dromtonpa had met people who had made this mistake. They’d studied for a long time, but they didn’t know how to practice. And so that’s what Lama Tsongkhapa is emphasizing here: That’s an error, and you haven’t really understood that the teachings are all meant for practice. How you get to putting all the teachings into practice is another story, but you at least have to start from this understanding.

3. Refraining from great wrongdoing

Then regarding ‘We will automatically refrain from wrongdoing’: Lama Tsongkhapa said that if you understand these first two points that we just went over—these first two greatnesses of the teachings—you automatically will be kept from wrongdoing.

In another way, you could say that these lamrim teachings encompass the three principal aspects of the path. The first of which is renunciation—a determination to free ourselves from all unsatisfactory conditions that we have in cyclic existence. The second one is bodhicitta—the heart that’s totally dedicated to others, where we want to become enlightened for their benefit, to free them from suffering. Then third is the correct view, which is the correct view of reality. That, of course, in the highest view is the understanding of emptiness of inherent existence. So these three principal aspects of the path are, when you think about it, the path. And the path is our mind, it’s pathways of our mind. All of these three actually help us to purify our motivation. Then with a pure motivation everything we do in our life becomes part of our practice. This is because the motivation is the chief determining factor of the value of what we do. It’s not the action or how things look to others. It’s actually our motivation. We can understand how by putting into practice the renunciation, the bodhicitta, and the correct view will help us to refrain from great wrongdoing. These things really all tie together.

When we think about our motivation, and even think about coming to teachings and things like that, we need to be careful in looking clearly at our motivations. It’s very easy for them to start one way (like virtuous) and move another way and get mixed with non-virtue. We don’t want to have motivations of listening to teachings so that we can be a know-it-all or anything like that. That’s just not what it’s about. If you do find those types of motivations in yourself, then you want to kind of clean them out—because they’re not going to lead to any place that is helpful for the path.

Setting a good motivation

Let’s talk a little bit about how it is the case that our motivation, when we have the three principal aspects of the path in our mind, is naturally going to be a good motivation. First with renunciation: What happens with that is we get out of just living our life for this life alone. We get beyond the happiness of this life. So that changes our motivation to one that thinks about the future; because if we just think about this life we’re not thinking about liberation. Then even if what we do looks like the Dharma, but we’re still thinking about the eight worldly concerns, that’s not Dharma. You haven’t started practicing the Dharma yet until you overcome these eight worldly concerns. (The eight worldly concerns are “the four cravings for gain, fame, praise, and pleasure and the dislike for their four opposites.) And that’s really, when you look at your life, a little bit hard to swallow. I say this because these things come up all the time—these concerns about gain and loss, and reputation, and all the attachment and aversions that we have that come up in our daily life. But we have to recognize those things and work with them, and then try to move our motivation from one of this life to full liberation.

With the second principal aspect of the path, the one of bodhicitta, then we enhance our motivation even more. Here because of the power of our motivation of having the bodhicitta in our mind, then any action we do becomes a cause for our full awakening.

And then with the correct view in our mind, we don’t see things so solidly and we don’t see things as inherently existent; and that allows us to see things as like an illusion. This too is very helpful on a practical level, even if it’s just sometimes an intellectual understanding, because it helps us not to be so attached to things, or so angry when things don’t go how we want. Even with the cursory understanding that we have now we can use that as a tool. Also this kind of wisdom of correct view actually gives us the courage to follow the bodhisattva path to full awakening, and of course this wisdom cuts the root of cyclic existence.

Thus having these three motivations can help all the things that we do in our life become something virtuous that’s leading us to enlightenment. This is why that Kadampa geshe gave the answer that he did: he understood this clearly from what Atisha had taught him.

4. To easily find the Buddha’s intent in giving teachings

One of the other greatnesses of these lamrim teachings and the benefits for a student is that it helps us to see what the intention of the Buddha is.

So there are these different themes that come up—and this is kind of a segue into these three levels of spiritual motivation. This is how Atisha organized the Lamp to the Path to Enlightenment text based on the three scopes or three levels of motivation of a practitioner. You could say that’s the general theme of the lamrim; but the more specific themes are actually these three principal aspects of the path. Now we’re going to try to go through the Dharma path as outlined in the lamrim and also pick out from Lama Tsongkhapa’s verses from the Three Principal Aspects of the Path text to see how they fit into the whole path.

One reference for a lot of the material I’m using tonight is Geshe Ngawang Dhargye. I really would recommend this book, especially if you want to read about renunciation. It’s a little challenging because the language is different. The translations are different from how we translate things. But once you have a pretty good understanding you can figure it out. Like “clearly evolved one” is the Buddha—so all these different expressions come up. But if you know the teachings well enough you can understand what he’s talking about because the translator has an interesting way of translating things. Geshe Ngawang Dhargye’s teachings on renunciation are just completely powerful, and I’d like to try to present some of those tonight. The book is called An Anthology of Well-Spoken Advice on the Graded Path of the Mind, but it’s usually just known as that first part, An Anthology of Well-Spoken Advice. It’s still available and has been out for many years.

Three levels of spiritual practitioner

What are these three levels of spiritual seekers that Atisha defined for us? I’m going to read this as it’s written in Anthology.

The first one is “Anyone who works fervently by some means for merely the happiness to be found in the uncontrollably reoccurring situations of future lives is known as someone of minimal spiritual motivation.” So that’s basically someone trying to have a favorable rebirth—still in samsara—and they’re working fervently to do that. What that person has done—and maybe it doesn’t like sound so much, but it’s more than what I’ve done—is they’ve gotten beyond the concerns of this life. That in itself is really something. And they’re trying to get into rebirths—to have precious human rebirth or maybe into the form or formless realms or something like that. They’re doing this by cultivating the causes of this. So that’s the first level of spiritual practitioner motivation.

The second level, as they wrote it, is “Anyone who having turned his or her back on the pleasures compulsive existence…”—which is cyclic existence. I like his translation, “compulsive existence.” It’s interesting. “…and with a nature turned from negativities,” —so they’re dropping all the negative actions— “works fervently for merely his own serenity”—his or her own serenity. “This is known as a person of intermediate motivation.” This is the person who wants to be free of cyclic existence; who wants to have the permanent peace of nirvana.

The third level or scope is, “Anyone who wishes to eliminate completely all the problems of others as he would the problems afflicting his own mindstream, and this is the person of supreme spiritual motivation.”

When we practice the lamrim as a Mahayana practitioner our goal is this third scope. We want to become buddhas. We try to make that bodhicitta our motivation so we can become buddhas for everyone’s benefit. But we actually practice ‘in common with’ the other two scopes; so we’re practicing all three scopes. We always use this terminology that we’re practicing ‘in common with’ the initial and intermediate level practitioners. We say that ‘in common with’ because actually our motivation is the third scope; and the practices we’re doing are ‘in common with’ them, because we need to generate those aspirations and realizations of the initial and intermediate levels.

The first scope – Initial level practitioner

Let’s talk first about this first scope, the initial level practitioners. The aspiration they are trying to develop is to die peacefully and have a good rebirth. That’s their aspiration. But how do they get to that point, how do they come to have that aspiration? You meditate on precious human life, impermanence and death, and the unfortunate realms of rebirth—the lower realms. That’s how you generate that aspiration. Once you’ve got that aspiration firm, then what do you do to actualize it? What do you do to actually attain a precious human rebirth or a rebirth in a higher realm? You have to practice refuge and karma and its effects. You have to make that the central part of your practice. So let’s explain this a little bit.

The initial-level practitioner—they’re contemplating death and impermanence. When you really soak your mind in this, you just realize that this life is transitory, there’s no stability in it, things like that. You know it’s going to end; and so you want to have a good situation. When you’ve seen all of the realities of the unfortunate situations you could have, you develop this fear or sense of alarm about that. You want something better than that. So those topics of contemplation are both how we get to the aspiration, and then how we actualize that aspiration.

To die peacefully and have a good rebirth: I want to contemplate this because it’s helpful for my mind. A lot of times with Westerners, teachers don’t like to emphasize the topics of death and impermanence or the lower realms and things like that—because sometimes we run into problems with these topics. But I find these to be very good for my mind. I just have to find a way to work with them so I don’t reject them. You don’t want to reject the teachings! You have to find a way to put these things in your own paradigm, because maybe you don’t believe—like, “What about all these lower realms?” Often times, first people think of those as psychological states. They work with it that way. When you think about it, you see things in the human and animal realms (that we do know about) that are very unfortunate, very suffering, very hellish kind of situations. So if you don’t want to think about your mind being in the lower realms, just think about something that you can see.

In The Three Principal Aspects of the Path this is the verse that, when the person’s attained this kind of thought, says, “By contemplating the freedoms and fortunes so difficult to find and the fleeting nature of your life, reverse the clinging to this life.” So that’s what the person has attained. When they’ve reversed the clinging to this life they have their thoughts on a future life. To take on these practices and the meditations in common with this initial level practitioner helps us to change our attitudes and our behaviors; and this actually helps us to be happier and to get along with others better. So that’s a very immediate thing. Most importantly, we have created the causes to have a peaceful death and a good rebirth; but even if we’re going for the third scope, no problem enjoying the benefits of the first scope. We want to have a peaceful death, we want to have fortunate rebirths.

Precious human life meditations

In order to understand the idea of the precious human life, we have to understand the meaning and the purpose of having a precious human life, or why would we make that aspiration? You wouldn’t have a motivation for it if you don’t know what it is. So we have to learn about that and see that the situation that we have now of a precious human life is actually quite rare and it’s very precious. We do those meditations so that we don’t take things for granted which is really easy to do. If we do this precious human life meditation well, our practice actually becomes very enjoyable and it’s with much less effort. In fact, Geshe Ngawang Dhargye says our practice becomes “effortless, wholesome and enjoyable.”

We have to understand the rarity of this life—it’s not just a human life, but a precious human life where you have the teachings and you’re interested in the teachings. When you think about it, if there weren’t people interested in the Dharma, if there weren’t people who had that interest, the Buddhas actually wouldn’t even come. The Buddhas don’t go to universes where there’s no one that’s going to listen to them. They spontaneously go where they’re needed. If no one’s interested, no Buddhas come. To me that’s a wakeup call.

What Geshe Ngawang Dhargye is pointing here where he brings this out is that “Hey, we’re in the situation now where things are pretty good. My life’s pretty good. I can have this very comfortable existence…” That’s often true. In many ways you can kind of arrange your life so that it’s very sheltered and comfortable and whatever. But oftentimes in that situation people don’t have a spiritual interest. So we can’t let our minds go there. We can’t get sidetracked in those ways. We have to think about the importance of spiritual development. That’s the only way we’re going to achieve true happiness for it allows us to change our mindstates and work on our attitudes, make constructive attitudes.

Precious human life meditations also helps us see if these changes are realistic. Like, do we have the ability to practice this path as we learn about it? Because when you look at a precious human life, what you’re looking at are: ‘Do I have the external factors and conditions? Do I have the internal conditions for practice? (These are described as the eight freedoms and the ten fortunes in the lamrim.) And if you have these, no matter what else is going on in your life—even if you have chronic back pain, even if you have loss of limb, even if you have this and that, whatever problems you have— you still have all the things you need to progress along the path. It’s important to do these reflections because it gives us a lot of energy.

Think about it. There’s no difference in our precious human life and Milarepa’s precious human life. I don’t think we think that way so I put that in bold print in my notes here. [Laughter] It always makes an impact on my mind.

Death and impermanence

When we think this way, it helps us to think, “Yes, I need to do this now.” And why? It’s because we don’t know how long we have to live. When you do these meditations, once you get the idea of your precious human life, what the value is, then you’ve got to turn to think about impermanence and death. Why? It’s because, hey, we never know when our death is going to come. Venerable Chodron’s father was not expecting to die at his birthday party, right? He’s gone—that’s how it is. I know so many people, like my sister had an aneurism burst in her brain—she happened to live. But my former boss’s brother had an aneurism and boom, gone. Those deaths happened very quickly.

Most of us by this age have many situations where we know of deaths that have come quickly, deaths that have come slowly. We need to not shy away from thinking about these things but to use them—because these kinds of reflections actually aren’t depressing at all. If you do them right they’re very energizing, they enlarge our perspective, they help us to get our priorities aligned with wisdom. Then these kind of thoughts and reflections help us to turn away from just being stuck in these eight worldly concerns of my pleasure, my happiness, “I want this, I want that”—that kind of thinking. Instead we think about cultivating compassion. We think about cultivating wisdom.

There are many benefits because it’s a very strong incentive to consider death. So think about the examples that we have that are so strong. This is what Shakyamuni Buddha did. He saw aging, sickness, and death, and he left his wife and his child because he wanted to find a solution for all sentient beings. Milarepa was in the same boat. He killed all these relatives—his uncle and all these other people—with what they call ‘black magic’ or whatever. Then he realized that he was going to die some day and look at what he had done, and then boom! He took that life and he just went forward to Buddhahood that very life! The same thing was true with Gampopa. He was an acclaimed physician. When his wife passed away, he began his search for the Dharma seriously at that point. There are so many examples of how death has been a huge motivator for people to move forward spiritually.

The unfortunate realms

The other stimulus that helps us to have this aspiration for a better rebirth is contemplating the unfortunate realms. I’d like to read from Geshe Ngawang Dhargye: “It’s not difficult to tell beforehand in which direction our next rebirth will be; most of us spend all our time building up negative potentials, and these lead only to a disastrous future. Just look at today: How many times since we have woken up have we become angry, thought ill of others, criticized, or been negative? How often have we done anything positive, constructive or beneficial for others?” We don’t like to really look at that, but this is what I love about his writing. It’s like, “Yes, look at my day, what did I do today?” And then, “What are the results of that going to be?” Where does the Buddha teach that unwholesome actions lead us? That’s the basic teaching on karma, right?

Shantideva says, “In this way, all fears and all the boundless problems originate, in fact, from the mind.” And the Buddha has said that, “All such things are the products of a negative mind.” So we need to see that if we don’t work with the negative mindstates that come up, the result can be very much a future suffering—however you can wrap your mind around what that might look like. Maybe you think of it as psychological realms, maybe you think of it as physical realms.

What Venerable Chodron says about that makes the most sense to me, if I can get her words straight: “Those lower realms are just as real as the reality of what you see around you”—like that. She speaks of lower realms that way sometimes, which I think is an expansive way to look this topic. But most of us rebel against even thinking about these kind of hellish states and suffering, and we don’t want to take them seriously. Also it’s easy to think these are just like a fantasy used maybe scare or frighten primitive people with these kinds of ideas. But Geshe Ngawang Dhargye is suggesting, and I’ll put this in my own words: If you have that idea in your mind, you’re digging yourself into a rut. He says, basically, that we’re being very close-minded and even unfair—because we don’t want to think about these kinds of situations. The idea that he’s presenting is: If your Dharma practice is just a ‘feel good’ kind of thing, then you’re not really using it for all its potential.

We have to look at the first teaching the Buddha gave, which was on dukkha or unsatisfactoriness. He did that for a reason: We have to see that we have a problem. And so not to be able to hear about these things like lower realms, well, I bring this up because of my own experience. I had a point when I first was meeting the Buddhist teachings where I had left the Catholic Church because I didn’t believe in hell. And then all of a sudden I hear about these hell realms in the Buddha’s teachings—I was almost out the door. I was so close to being gone from ever being a Buddhist practitioner. That’s why I bring this up. I see how immature I was and I’m just so grateful that I didn’t follow that thought. It was really close-minded, uninformed, and immature.

But if we become aware of all the problems that exist in samsara, then we’ll develop a sound determination to be free from all of them, not just some of them. That’s a great benefit. We can open our minds to try to understand this and find a way to work with it in our practice. I would refer you to Geshe Ngawang Dhargye’s book, because he has some really great examples about how we don’t let our mind open to this, which we don’t have time for tonight.

Taking refuge

To continue, once you have developed this first aspiration then what do you practice? As I said before, the meditations for this are on refuge and on karma. In terms of refuge, Venerable Chodron has said that once we’ve gotten our mind wrapped around death and impermanence and so we’re preparing ourselves for our death and our future rebirth, we see that we need guides. That’s why we turn to the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha—because we need protection and guides to help us with the situation that we’re in. Unless we can see ourselves in that situation of needing protection, why would we need guides?

Refuge is based upon this wisdom fear. What are the causes of refuge? They are fear (wisdom fear) and faith (or confidence or conviction) that the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha are reliable guides. For a Mahayana practitioner another cause is compassion. They say oftentimes that taking refuge in the Three Jewels is “the excellent door for entering into the Buddhist teachings,” and that “renunciation is the door for entering the path,” and that “bodhicitta is the door for entering the Mahayana.” You might hear those because that’s commonly said.

A really good point Geshe Ngawang Dhargye makes about this is: When we see our situation in cyclic existence, we also have to come to the place where we see that our own techniques for dealing with it can’t overcome it. You can live your life moving from one thing to another and to another. But unless you see the big picture and you look at how you’re actually living your life and what you’re doing, then you have to really ask yourself, “Well, is this going to work? Is distracting myself with playing classical guitar for hours a day, which is something I used to do, going to free me cyclic existence? Is entertaining my next interest—all my interests that I had in this life, moving from one interest to another interest—yes, maybe they were wonderful, but are those things going to overcome this situation?’ So we have to be real clear with that.

Next we have to understand that this situation that we’re trying to be relieved from is actually coming from within. It’s our own counterproductive emotions. These are the trouble-makers and we have to seek protection from them! How bizarre is that? So actually we’re trying to liberate ourselves from our internal enemies. This is what His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “Since what we’re looking for is liberation from internal enemies, a temporary refuge isn’t sufficient.” That’s very insightful.

We’ve just covered the first cause, this wisdom fear that we cultivate. Second is this faith or conviction that we cultivate. That’s where we really have to take a look at the path, and understand it, and see that the Buddha is a reliable refuge because there’s a real possibility that what he’s saying works. We basically have to do just that.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama in his writings lays this out are very clearly. We have to develop a clear understanding of what the Three Jewels are, but in order to do that we actually have to understand the four noble truths. In order to do that, we have to understand the two truths. This is because if we don’t understand the two truths about conventional reality and ultimate reality and how all that works (which is the philosophical basis) then when we try to understand the four noble truths it’s all kind of hazy. And if that’s hazy and we don’t understand the four noble truths, then taking refuge in the Three Jewels isn’t really very stable. Then it would be just mere words. You’re just saying these words, but you don’t have an understanding of it—so we really have to educate ourselves.

Three points of reasoned faith

That’s why we learn about the teachings, and contemplate, and meditate on them. Over time the refuge deepens as your understanding deepens. We have to gain conviction. The thing is as we gain understanding, we gain conviction or reasoned faith. Three points have been explained that we need to develop this conviction and that we will develop conviction in. The first one is that the basic nature of the mind is pure and luminous. That’s a very important point in Buddhist teachings. With this we come to understand that the afflictions are based on ignorance that apprehends phenomena as existing in the opposite way that they actually do, and that this isn’t the nature of our mind. That’s a huge understanding. Next we see, due to that reality, that it’s actually possible to cultivate antidotes, very powerful antidotes, to these afflictions that are based on this ignorance. Lastly, we determine that these antidotes are realistic and beneficial mental states, and they can root out the afflictions. We can’t just stay with prayer. We have to come to a place where we understand these points.

Karma

We’ve briefly completed the part about refuge. Now with karma, what is the first thing the Buddha says after we have taken refuge? He says you’ve got to stop harming others and yourself.

Here’s short quote from Geshe Sopa that sums this up very quickly: “The most important thing to do in the beginning is to take refuge in the Three Jewels; this is the way to enter deeply into the teachings of the Buddha. The next step is to examine causality, drawing from examples in your own experience until you’re convinced that positive actions result in happiness and non-virtue leads to unhappiness. Strong trust in the relationship between cause and effect is the basis for living a life of virtue and engaging in spiritual training. To obtain happiness and avoid misery, you have to accumulate their causes: practicing virtue and eliminating non-virtue. It’s not easy to control your actions, and it requires great mental and physical effort. If you don’t have the confidence in the truth and the benefit of the practice, you’ll not be able to change your attitude and your behavior. This is why faith in karmic causality is the root of all happiness from worldly joy up to the bliss of supramundane happiness, liberation, and enlightenment.” That just says it all.

I’ve spent most of the time tonight on the initial scope, because this is where we are essentially. We want to study all this, all the teachings of all the three scopes, and just keep cycling through and cycling through with these teachings. In fact, Venerable Chodron told me once that you want to always balance these three in your spiritual practice: renunciation, bodhicitta, and wisdom. Don’t let it become lop-sided. That’s been very helpful advice and it also boils down to something I can remember.

So we don’t just stay with this first scope, but realistically that’s where most of us are. We’re still thinking about this life—so we have to not jump through that hoop too quickly and go to the other parts of the practice.

The second scope – Intermediate level practitioner

The second scope is the path in common with middle-level practitioners. What is their aspiration, what are they trying to develop? They’re trying to be free from cyclic existence, to become liberated, attain nirvana. That’s the first of the three principal aspects of the path—renunciation. How do they meditate to develop that kind of aspiration? They meditate on the Four Noble Truths, the disadvantages of cyclic existence, the nature of the afflictions, and the factors that stimulate their arousal. Here I’m summarizing these points at first, and then we’ll talk a little bit about them.

Once you’ve meditated on those topics, and you’ve developed that aspiration, then what do you do to actualize that aspiration to liberate yourself from cyclic existence? That’s when you do practices of the three higher trainings: ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. This wisdom is the correct view, and that’s the third of the three principal aspects of the path. So the three principal aspects are completely woven within the lamrim.

Freedom from cyclic existence

In developing this aspiration to be free from cyclic existence and attain liberation, what happens? Basically we see, “Okay, a good rebirth is nice, but it’s going to end”—and we have to really take the big picture here and get ourselves out of cyclic existence altogether. Here we see all the various disadvantages of samsara—all the different sufferings, and we want to be free completely.

This is where Lama Tsongkhapa in The Three Principal Aspects of the Path says, “For you embodied beings bound by the craving for existence, without the pure determination to be free from the ocean of cyclic existence, there is no way for you to pacify the attractions to its pleasurable effects.” You hear that? That’s important. We have to get to this place of renunciation. “Thus from the outset seek to generate the determination to be free.” Then he goes on, “By contemplating the leisure and endowments so difficult to find and the fleeting the nature of your life, reverse the clinging to this life.” So that was the first scope. And then, “By repeatedly contemplating the infallible effects of karma and the miseries of cyclic existence, reverse the clinging to future lives.” There he takes us all the way to wanting to become liberated.

Renunciation we’ve already talked about a bit in the first scope—because it naturally comes up. This is not a small realization. It brings incredible energy and focus to your practice—which helps us not to be distracted by the concerns of this life. Why is that? It’s because we’re clear about the meaning of our life and what we’re going to do. It’s something that’s more important than just this life, which is get out of this larger situation. So instead of trying to decorate our prison cell, and be content to be there, and tweaking samsara, now we have this aspiration to get out—and so we meditate on the Four Noble Truths.

Eliminate the causes of suffering: Self-grasping ignorance

Maitreya said that this is the core perspective, “Just as you recognize that you’re ill and you see you can eliminate the cause of illness by attaining health, by relying on a remedy, so recognize suffering, or dukkha, eliminate its cause, attain cessation and rely on the path.” That’s basically our job. The self-grasping ignorance we have to come to see as the root of cyclic existence, and liberating ourselves from it is going to free us from all afflictions and karma. Our obstacle to liberation is tied to the view of the self; and that’s related to the self-grasping ignorance. It’s this view of self (called view of personal identity or view of the transitory collection) that is the real root of samsara. That view leads us to have afflictions, which lead us to actions, which keeps us just going, going, going around in samsara.

This is Nagarjuna speaking, “Through the cessation of karma and afflictions there is nirvana. Karma and afflictions come from conceptualization, these come from elaboration, and elaborations are ceased by emptiness or ceased in emptiness.” The Dalai Lama translates this differently in a another text. He says, “When afflictive emotions and actions cease, there is liberation. Afflictive emotions and actions arise from false conceptions. These arise from erroneous proliferations, and these proliferations are ceased in emptiness.”

Basically we find that it’s these subtle things going on in the mind, these distortions (like the four distortions, etc.), that lead us to have this elaboration of inherent existence. Seeing things as inherently existent is the basic problem, especially the view of the self. It’s not so big deal that I think this clock exists in and of itself. But the fact that I conceive “I” to exist inherently makes me so important; it makes the afflictions arise and then I do karma—all kinds of actions. Then I cycle around cyclic existence. So that’s really where we have to get to.

Three types of dukkha

We have to see the disadvantages of cyclic existence to want to get out. We’ve talked about that a little bit. Another way that that’s done is by talking about the three sufferings: First is the dukkha of pain—which is like gross suffering. Even animals have that fear. They want to be free of suffering. Second, there’s the dukkha of change—which non-Buddhists religious folks understand as well. It’s that you have to turn away from so called pleasures, because they’re unsatisfactory. They don’t last. The third one, which is uniquely Buddhist, is the dukkha of pervasive conditioning. This is really tying into the wisdom aspect in a way too. We have to see that our mind-body complex is in the nature of being under the control of these afflictions and karma. This is the basic condition that we live in. This induces all kinds of suffering in the future. And this is what we want to transcend. These three kinds of suffering are some of the disadvantages of samsara.

What are afflictions?

So what are afflictions? Asanga defines them as, “A phenomena that, when it arises, is disturbing in character and that through arising, it disturbs the mind-stream.” I think we’re all pretty aware of this. It’s disturbing to have afflictions.

What are the causes of our dukkha in cyclic existence? It’s the afflictions, the negative emotions and disturbing attitudes in our mind. So there are six main ones: attachment, anger, pride, ignorance, deluded doubt, and various distorted views. Why do these arise? Well, they arise because we have seeds of them in us. They arise because we have contact with objects, “Oh, I’ve got to have this!” They arise because we have detrimental influences around us—like bad friends. They arise because of the different kind of verbal stimulation around—like media, and books, the Internet, and whatever things that we’re around. They arise because we’re creatures of habit and we have habitual ways of thinking, habitual emotions. They arise because we have this inappropriate attention. That’s the mind that pays attention to the negative aspects of things; that makes us have biases and jump to conclusions and be judgmental. That’s the mind that makes up all the dramas and stories in our life. We impute all these meanings on things when things happen—like we have this deluded perception and then we write a novel about it. This is the inappropriate attention. So these are the factors that cause afflictions to arise in our mind.

Once you’ve seen all of that, which of course, it takes years to understand a lot of that—then you go the Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas: “In brief, whatever you are doing ask yourself, ‘What’s the state of my mind?’ With constant mindfulness and mental alertness accomplish others’ good. This is the practice of bodhisattvas.” We’re only in the second scope here. We aren’t into the third (bodhisattva) scope yet. But the point is: How do you deal with afflictions? Well, you definitely have to have mindfulness and introspective awareness onboard. Otherwise we’re going to be lost! You can have all teachings under your belt, and if you don’t have—as Shantideva says, “You’re between the fangs of the afflictions if your mind is distracted.”—right? So we have to develop our mindfulness and be paying attention to…it could be your ethical behavior in this situation.

The three higher trainings

Once you have the aspiration to liberate yourself, then what do you do practice? Practice the three higher trainings—which said in another way is the noble eightfold path. But three is easier to remember than eight, so we’ll talk about three. [Laughter]

The three higher trainings are ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. These are how we free ourselves. When we talk about ethical conduct, if you boil it down, you basically want to avoid the ten nonvirtues—that’s the long and short of it. With concentration you want to eventually develop single-pointed concentration so you have this powerful mind. And with wisdom you understand the correct view, which we’ve talked about just very briefly. This understanding that the appearances of this world are not as they seem, that is, we think things are inherently existent and they aren’t.

The reason those three come in that order: If you don’t clean up your ethical conduct, you’ll never be able to develop concentration. If you don’t develop single-pointed concentration, you’ll never be able to have direct realization of emptiness—because that’s a precondition to the direct realization of emptiness. You have to have the direct realization of emptiness to free yourself from samsara. So these things are very related. They are the same in the eightfold noble path. It has the same ideas just presented differently.

One last thing that we’ll say about this scope, and then we’ll move to the next scope, is something that the Dalai Lama said in his book called Becoming Enlightened. It just gives us more of a flavor for this kind of wisdom: “When, through meditative analysis, you realize the lack of inherent existence or emptiness within yourself, you understand for the first time that your self and other phenomena are false. They appear to exist in their own right, but do not. You begin to see things as being like illusions, recognizing the appearance of phenomena yet at the same time understanding that they are empty of existing the way that they appear. Just as physicists distinguish between what appears and what actually exists, we need to recognize that there is a discrepancy between appearance and the actual fact.” That’s one brief way to explain the correct view.

The third scope – Advanced level practitioner

The third level is the advanced practitioners. This is basically the second of the three principal aspects of the path—bodhicitta, the altruistic intention. This is the intention to become a Buddha in order to help alleviate the suffering of and benefit all sentient beings. There are two different ways to cultivate this. But to develop bodhicitta we definitely first have to get to a place of equanimity. There are many meditations to cultivate equanimity. After that we do practice either the seven-point instructions on cause and effect or the equalizing and exchanging self for other practices to generate bodhicitta. There is also a method where they combine these two methods into one.

Once you’ve developed that bodhicitta aspiration, then what do you practice to actually reach the goal of full Buddhahood? That’s when you practice the six far-reaching practices, the four ways of gathering disciples, and the path of tantra. We’ll just say a little bit about each of these and then we’ll try to leave time for questions.

This third level is the path of the advanced practitioners. So we’ve practiced in common with the initial and the middle-level practitioners, but we don’t stop there with those objectives. We’re not going to be satisfied with an upper rebirth, and we’re not going to be satisfied just with liberation. What are we doing?

The altruistic intention – Freeing all sentient beings

Our motivation is based on this: We’re seeing all sentient beings—they’ve been kind to us in our many, many lives since beginningless time—and we’re all in the same situation. We’re all in this situation of recurring birth, aging, sickness, and death. So we generate this bodhicitta, this aspiration to attain full awakening in order to benefit all of these kind mother sentient beings most effectively. This is the motivation.

In The Three Principal Aspects of the Path it comes in this verse:

Swept by the current of the four powerful rivers, tied by the strong bonds of karma which are so hard to undo, caught in the iron net of self-grasping egoism, completely enveloped by the darkness of ignorance, born and reborn in boundless cyclic existence, unceasingly tormented by the three sufferings—by thinking of all mother sentient beings in this condition, generate the supreme altruistic intention.

In that verse Lama Tsongkhapa has taken us from the second—even the first scope, where we were talking about karma, “the strong bonds of karma.” He’s taken us through “the darkness of ignorance” so we see that “boundless cyclic existence.” We don’t want to be born and reborn in that with its the three sufferings. Then when we think of all mother sentient beings in this situation of these three sufferings then we generate this altruistic intention.

Aryasura says that “When people see that joy and unhappiness are like a dream and that beings degenerate due to faults of delusion, why would they strive for their own welfare, forsaking delight in the excellent deeds of altruism?” This is a verse that I find quite helpful, because it brings up these points that happiness, unhappiness—these things are like a dream. It brings up that illusion-like quality that they’re talking about. He also brings up this point that sentient beings—we degenerate due to these delusions in our mind. When we see that, when we really see that, how could we not want everyone to be free of that situation? I mean, how would we not?

Why would you forsake that, when you see what the excellent deeds of altruism are—these bodhisattva practices? These are just fantastic practices. And we get this great side benefit of bringing a lot more happiness to our own lives. It just comes as a by-product. But the things that you do as a bodhisattva—the six practices of generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude (patience), joyous effort, concentration, and wisdom—when you just think of all the things those entail, why would anyone want to forsake that? I can’t even imagine myself, personally, wanting to be in the permanent peace of nirvana. I have a great admiration for this in seeing how hard it is to attain, but I’m much more interested in the bodhisattva ideal.

We want to raise our spiritual practice up to that level, to the point where seeking enlightenment in order to benefit others more effectively is our spontaneous inner motivation. Once it’s actually spontaneous, that’s when you’ve actually entered the bodhisattva paths. That’s the path of accumulation. Remember there are three vehicles: the hearer and the solitary realizer whose goal is liberation, and then the bodhisattva vehicle whose goal is full awakening.

When you enter the first two (hearer and solitary realizer), the way you enter is through having renunciation. Lama Tsongkhapa described this in the verse about “When day and night unceasingly your mind…” wants to be liberated from cyclic existence. That’s the mark of renunciation. If you have that as your motivation and you don’t have the bodhicitta motivation, that’s how you enter the vehicle of either of the hearer and solitary realizer. But when you first enter the bodhisattva vehicle, what gets you there is this spontaneous bodhicitta. (For all three vehicles this is also called the path of accumulation.)

Compassion and the six far-reaching practices

Bodhicitta is the seed of all the Buddha’s qualities. Why is that? Basically when you look at the six far-reaching practices, what underlies all of them is compassion. You can almost call it the seventh aspect, but it isn’t. It’s underlies all of the others.

Bodhicitta is actually a double aspiration, it has two intentions. One is to help others and the other one is to attain full awakening in order to be of highest service. And when have you attained this? The Dalai Lama says that when bodhicitta is as strong outside of meditation as it is in meditation. But it also has to be spontaneous to reach that first path of accumulation.

I’m not going to go through the equanimity meditations that I love—my favorites—and all the bodhicitta ones like the seven-point instructions for cause and effect, and the equalizing self and others, which are beautiful. But remember, these were how you get the motivation of bodhicitta, but then what do you do after you have that motivation? Then you practice the six far-reaching practices. We do these six practices to ripen our own minds—some of them are for our own benefits and some are for others benefit.

It’s Nagarjuna who explains about compassion. “In Precious Garland Nagarjuna speaks of the six far-reaching practices and their corresponding results, and he adds the seventh factor—compassion, which underlies the motivation to engage in the other six. These six far-reaching practices become far-reaching when they’re motivated by this altruistic intention”—so you could be generous, but if you aren’t generous with this motivation to become fully awakened, it’s not far-reaching. “And they’re considered purified and realized when they’re held by wisdom that realizes the emptiness of the agent, the object, and the action.” That’s something we always want to do when we work on these six perfections. We want to also understand them within the sphere of emptiness.

Those two points are important. It’s not just, “I’m being ethical. It’s not like, “I’m just being patient.” It’s not like ‘I’m just trying to develop this concentration.” All of those six far-reaching practices are far-reaching because they’re motivated by the altruistic intention; and they’re purified and realized when they’re held by this wisdom realizing the emptiness. We always seal these practices with our understanding of emptiness.

Also remember that we always want to make dedications. How do you get a precious human life? Let’s go back a little bit. Ethical conduct gets you a human life, but what about a precious human life? The causes are ethical conduct, having in previous lives done the six far-reaching practices, and then making prayers of aspiration dedicated to having precious human lives. (We of course also dedicate for attaining Buddhahood.) We want to make sure that we keep that in mind when we do these six far-reaching practices.

To attain Buddhahood the next thing that you practice is the four ways of gathering disciples. We do this in order to ripen others’ minds—by gathering disciples through our generosity, through teaching them, through encouraging them to practice, and then embodying the Dharma in our life. These are often incorporated in the six far-reaching practices and so these are also part of the main practices of a bodhisattva.

The path of tantra

Lastly to attain Buddhahood is the path of tantra. The sutra vehicle is the path that follows the sutras. These are teachings that the Buddha gave when he was appearing in the aspect of a monastic. This includes teachings of the paths of the hearers, the solitary realizers, and the bodhisattvas. The tantric vehicle are the paths and the practices that were described in the tantras, These were given by the Buddha when he appeared in the form of Vajradhara.

To close, Lama Tsongkhapa gives us some advice about all of this. He says, “Therefore, having relied upon an excellent protector”—which is our spiritual mentor and the Buddha—“solidify your certainty about the way that all the scriptures are causal factors for one person to become a Buddha. Then practice those things that you can practice now. Don’t use your inability as a reason to repudiate what you cannot actually engage in, or turn away from; rather think with anticipation, ‘When will I practice these teachings by actually doing what should be done and turning away from what should not be done?’ Work at the causes for such a practice, accumulating the collections, clearing away obstructions and making aspirational prayers. Before long, your mental power will become greater and greater, and you will be able to practice all the teachings that you were previously unable to practice.”

If you look at lamrim Lines of Experience by Lama Tsongkhapa he always has this line: “I, the great yogi, this what I did and you should do this too.” He always says these things—like you need to make these aspirational prayers, and these other aspects of what we need to do. So we need to be complete—like what he says here: “Accumulate the collections that generate the merit, clear away the obscurations, make aspirational prayers, and your mental power will grow.”

Questions and Answers

Audience: Do you think it’s possible to reach full bodhisattva realizations in this lifetime?

Venerable Thubten Tarpa [VTT]: For who, anyone? Yes, I think it is. I think there are people who can become a bodhisattva in this lifetime—definitely—because there are people who have practiced. The first part of becoming a bodhisattva is this spontaneous bodhicitta. Yes, I do. It’s actually, they say, a little harder to realize than emptiness in some ways, but still. Yes, I do. What do you think?

Audience: I was a bit confused by the question of ‘full bodhisattva realizations.’ Yes, I do think it’s possible to generate spontaneous bodhicitta.

VTT: Oh, ‘full bodhisattva realization.’ Well, full bodhisattva…I don’t know; I take this to mean spontaneous bodhicitta.

What we do now is we contrive our bodhicitta. And that’s what we need to be doing because that’s how we are going to get ourselves there. If we don’t do that we’ll never be able to have it become spontaneous. What can make you have more certainty in this is to see how we’re creatures of our habit with our negative things. That’s the one good thing that comes out of that—when you see how some things are so habitual. Then you realize that you can create new habits, which we also know. Then you realize, “Well, I can create good habits.” And that’s really what you’re asking yourself to do. Yes, and I think things can become spontaneous. They have in other things in my life, why wouldn’t they with that?

One time Venerable Chonyi was asking, “Well, I’m older and if in this life…if I really am not going to be able to study all the great treatises and this and that, what’s realistic?” And Geshe Wangdak replied, “If you feel like you don’t have that much time—because maybe you came to the Dharma later in life,” or this or that, he said, “Cultivate bodhicitta.”

That makes total sense because if you cultivate bodhicitta you’re going to have the motivation to do everything on the path. If you cultivate any of the other ones, you’re not necessarily going to have those motivations. Whereas with bodhicitta you’ll plant seeds that in this lifetime and future lifetimes will lead you to full awakening—with that one thing.

Again, remember what Venerable Chodron said: We always want to balance our practice with study and meditation on renunciation, bodhicitta, and wisdom. This doesn’t mean you’re doing all three at once, but you don’t want to just get lopsided. You’ll find that if you do get lopsided then things will probably get a little out of balance and you’ll need to even it out again. She told me once that if you just do all the philosophical studies all day long, your mind can get real dry, and you need to moisten your mind with bodhicitta. And for me personally, I find the teachings on renunciation really give me energy.

Audience: Someone’s asking: Can you redefine the difference between the precious human rebirth and an ordinary human rebirth?

VTT: Yes. Ordinary human rebirth is a human, but they don’t have the internal and external conditions of a person with a precious human rebirth. And those are basically the mental and physical capacity to take in and think about the teachings. You could be born human, but you could be so developmentally delayed that your brain could be so unable to understand enough to be able to process and even think well. You have to be able to think. It helps to have all your mental and physical capabilities. You have to have the leisure where you are not in situations that make it impossible to put your mind on the Dharma. If you’re in the lower realms, say in the hell realms—having so much pain that you can’t focus on the Dharma. You have to have the kind of situation where you can put your mind on the Dharma.

The Buddha has to have appeared and taught, the teachings still have to be here—there are conditions that you have to have. They basically boil down to having the internal resources like the interest and the internal physical and mental situation, and then the external resources. If you don’t have any teachings in your country, for example, you can’t practice.

And then, of course, the causes of the precious human life are not just the ethical conduct, which is what gets you a human life. But they’re ethical conduct, the six far-reaching attitudes, and we make these dedication prayers. Those are the causes to have a precious human rebirth in the future. But if you only do a part of those causes, you’re only getting a part of the result—so people who just practice ethical conduct, which are many people on this earth, they aren’t necessarily creating the cause for a precious human rebirth. They might have a human rebirth and never meet the Dharma.

Dedicating merit

We’ll make the dedication prayers and we can dedicate any merit and virtue from having thought about these teachings to, first to Bernie Green, Venerable Chodron’s father, for his precious human rebirth, and to all beings in the bardo—I’m sure there are many—and all the beings in all the various realms, to always have precious human rebirths in the future.

Lastly, this is one of the dedications that Venerable Chodron has taught us: “May we always meet qualified Mahayana and Vajrayana teachers; may we recognize them, may we follow their instructions, and may we do this to become fully awakened to benefit all.”

Note: Excerpts from Easy Path used with permission: Translated from the Tibetan under Ven. Dagpo Rinpoche’s guidance by Rosemary Patton; published by Edition Guépèle, Chemin de la passerelle, 77250 Veneux-Les-Sablons, France.

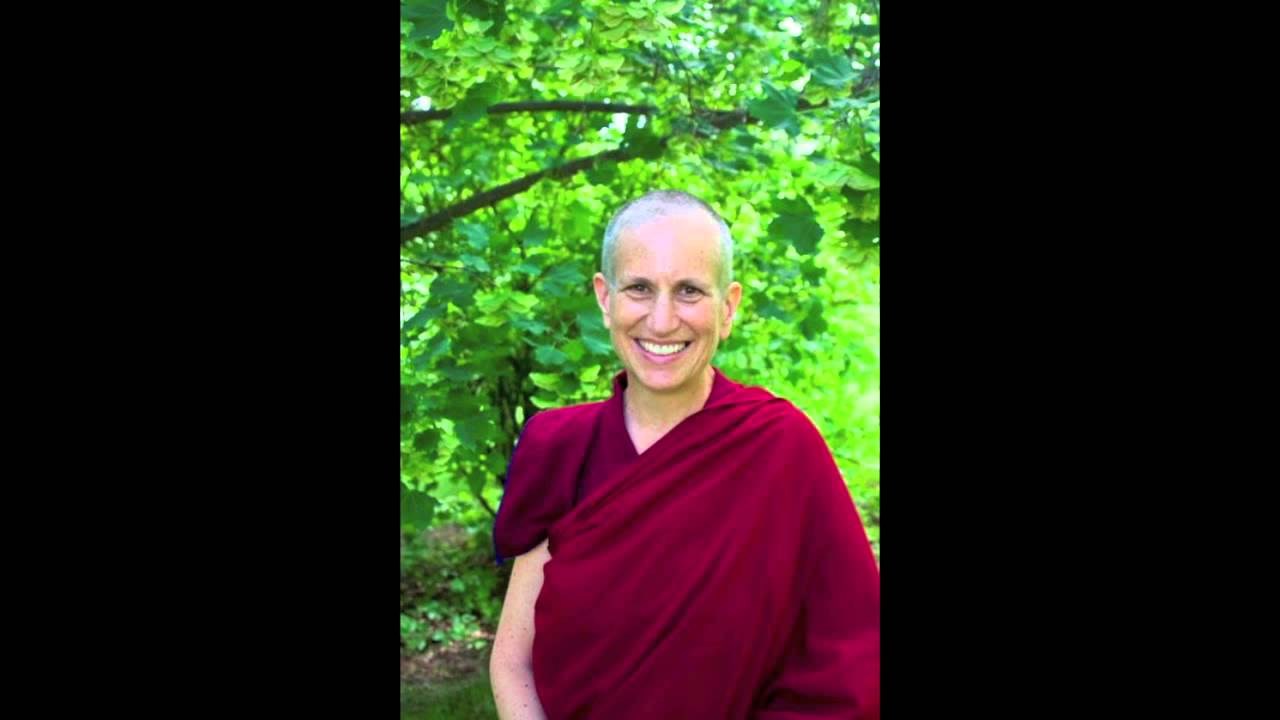

Venerable Thubten Tarpa

Venerable Thubten Tarpa is an American practicing in the Tibetan tradition since 2000 when she took formal refuge. She has lived at Sravasti Abbey under the guidance of Venerable Thubten Chodron since May of 2005. She was the first person to ordain at Sravasti Abbey, taking her sramanerika and sikasamana ordinations with Venerable Chodron as her preceptor in 2006. See pictures of her ordination. Her other main teachers are H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Sakya and H.E. Dagmo Kusho. She has had the good fortune to receive teachings from some of Venerable Chodron's teachers as well. Before moving to Sravasti Abbey, Venerable Tarpa (then Jan Howell) worked as a Physical Therapist/Athletic Trainer for 30 years in colleges, hospital clinics, and private practice settings. In this career she had the opportunity to help patients and teach students and colleagues, which was very rewarding. She has B.S. degrees from Michigan State and University of Washington and an M.S. degree from the University of Oregon. She coordinates the Abbey's building projects. On December 20, 2008 Ven. Tarpa traveled to Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights California receiving bhikhshuni ordination. The temple is affiliated with Taiwan's Fo Guang Shan Buddhist order.