What changes when you become a monastic

A talk given during Sravasti Abbey’s annual Exploring Monastic Life program in 2013.

- Appearance, name, livelihood/occupation, dress, shelter, diet, responsibilities towards community

- Minimizing possessions, simplifying wants, sharing resources

- Not doing business or having a job but depending on the kindness of others, being of service to the community

http://www.youtu.be/ILGXoTGHUS8

Let’s recall our motivation and remember that the bottom line motivation for becoming a monastic is to have the aspiration for liberation; then as Mahayana practitioners we also want to add onto that the bodhicitta motivation. Our monastic life has to have a deep purpose and meaning, a very clear motivation. It’s not something that we just fall into or do on automatic, but that we’re quite consciously choosing.

Dispelling myths about the monastic lifestyle

I was saying in the motivation that we’re consciously choosing this lifestyle. I think that’s quite important. We’re not doing it just on automatic. When you’ve been ordained for a while you have to really make this something you keep coming back to every day, “This is why I’m doing what I’m doing, this is why I’m doing what I’m doing.” It’s not just that you ordain and you space out and just keep doing what you’re doing and what monastics are doing, but without really thinking why you’re doing it. This motivation is quite important to keep very vivid in our mind. Not only for monastic life but for Dharma practice in general.

Today Venerable Tarpa and Venerable Yeshe are in Spokane shopping. Now you might say, “Well if monastics are going shopping…” but the work that they’re doing is in service of the sangha. When we live together as a community then we divide up the different jobs and the different things and people do them all in service for the sangha. Although we try and arrange it so that nobody has to miss teachings and so on, sometimes there’s things that come up. Like when you’re building a building and you need a stove—and the only hours they’re open are in the daytime that are the time when the teachings are—then clearly you have to miss one of the regular activities the sangha is doing.

I think it’s important because lots of times we have this airy-fairy idea of monastic life. Like you ordain and then after that all you do is meditate, and preferably all alone in a cave, and then realizations just shower upon you magically as you float up in the sky and that are blissful. Oh! I’m sorry to disappoint you but it’s really not like that. It’s like the precepts are designed for ordinary beings and we’re ordinary beings. They help us become extraordinary beings, but we really need to get over this fantasy of what monastic life is: like I’m just going to study and meditate—that’s all I do, I don’t have to do any work for anything. Well, actually if you’re living in a community, you have to do something because everybody has to work together to sustain the community.

Even if you live on your own, you have to do something. It’s not like in your cave they have an instant water dispenser and kerosene flows through the rock—I’m sorry you don’t use kerosene… that there’s a ready-made gas stove, propane that automatically gets filled. And anything that tears, your robes that tear, automatically get fixed. No, I mean like the meditators above Dharamshala, they all carry their own water. You have to walk to the stream with a big barrel or pot or whatever it is and bring your water back. And then if you’re fortunate a disciple brings you kerosene, you don’t have a nice gas stove. And you have to sew your own stuff when your robes break and if your hut needs repairs you have to repair them.

What I’m trying to say is that people have such a fanciful idea sometimes of monastic life. Then they’re very disappointed afterwards when they realize, “Gee I still have to do things to take care of this body and I still have to do things to you know to take care of the community.” They somehow feel like, “Well now I’m a monastic and everybody should take care of me.” No. Lama Yeshe, one of the big things he really hammered into us, and I have this very vivid image of him as he really made it a point one day, to pick up his mala and he said, “Your mantra is, ‘I the servant of others, I am the servant of others, I am the servant of others.’ That’s got to be your motivation for whatever you do. Don’t expect other people to serve you.”

Having said that, we do receive a lot of offerings and services from lay people, and we depend on the lay support a great deal. But knowing what it’s like ourselves to serve others, then we should really make sure that we appreciate the service we receive and not just take it for granted and not have some kind of idea of, “Well I sit in the front row because I’m a monastic, so they should do stuff for me.” That kind of arrogant thing, which sometimes you find amongst people, that just doesn’t fly. That’s the easiest way to have lay people disrespect you, is if you’re arrogant and you have a big mouth or a bad mouth. Easiest way to lose respect.

So we’ve always got to work on our motivation. Then when we serve to really have an attitude of serving, not an attitude of, “Oh well okay I guess somebody’s got to do this, gee I hope it can be somebody else next time!” But to really kind of appreciate that opportunity and do our service work with joy. I mean we have to keep our precepts while we are doing service work. Don’t we? Because so many of the precepts regard like how we get along with other people and how we treat other people, so those precepts are for when you are dealing with other people! They’re not for when you are in your fanciful dream in a cave where you’re up there complaining because they don’t have all the modern things you want and at the same time hoping that everybody all your friends know how renounced you are and what a great yogi you are. So, to serve with joy.

And everybody contributes something different according to their different abilities. But also what they do at some monasteries…the monasteries are quite different. In the Tibetan monasteries because they have such a huge population of people who ordain and many of them ordain when they were young, their philosophy is ordain a lot of people and out of a big batch you’ll get a few gems and then the rest will serve the monastery. So you have a whole group of people who after some years of education, that way of teaching doesn’t speak to them and so they prefer very much to offer service. In the Chinese monasteries they do it a little bit different. You get a basic education program and then after that everybody offers service. But even during the basic education program, they consider part of it’s learning to do the different jobs in the monastery. So everybody rotates taking care of the altar, everybody rotates being in the kitchen or doing this or that. There are some jobs that have specific skills so those you have to have people who have those skills, but many others you rotate so you get an idea really of how the entire monastery runs and an appreciation of the jobs that everybody does.

In the Tibetan monasteries it really is quite different, there is much more distinction. The Rinpoches don’t work. If you enter a monastery and you have benefactors, then they can make a large donation to the monastery and then you don’t do as much work. When they were first exiled in India then almost everybody, not everybody, most people worked in the fields. Now the monasteries are richer so they pay the Indians to work in the fields so the monks have more time for their practice. So things are different in each kind of place.

What changes when you become a monastic

Today I thought we’d talk about what changes when you become a monastic. I’ll just briefly read the list and then go through and talk about them. One is a change in appearance; and then second is a change in your name; third change in livelihood or occupation; fourth change in dress; fifth change in diet; sixth, a change in your lodging or you shelter; and seven, change in responsibility towards the Buddhist community and society.

Change in appearance and dress

I’ll talk about change in appearance and change in dress together as they kind of come together. So our appearance does change when we ordain doesn’t it? One thing is shave your hair, shave your beard. That is the way that it’s been since in Ancient India. I think one of the reasons is because hair is, in a way, an adornment in how we have our hair creates an appearance and makes us attractive. Since we aren’t trying to be attractive to anybody else then there’s no need to have the hair. It makes it so much easier! You don’t have to worry about how your hair looks or what color it is, the guys don’t have to worry about if they have hair or don’t have hair because it all gets shaved off anyway. Not only is our hair specifically referring to our vanity about our physical appearance, which applies to men as well as women, but also shaving it off represents cutting off ignorance anger and attachment, the three poisonous minds that are consistently creating problems for us and keeping us bound in samsara.

Another change in appearance is we don’t wear jewelry or ornaments or perfumes. Without hair you don’t have all the hair ornaments. We don’t wear any jewelry that could be adorning in any way. Now the question of watches comes up a lot. In Tibet when they first had watches they didn’t know what they were for, so they were quite a status symbol. Even here too, what kind of watch you have, it creates an image doesn’t it? It kind of shows what kind of person you are: if you have one of those ones with all those different dials and barometer pressure and this and that, or if you have a Rolex. You create an image, you draw attention to yourself through your watch. That’s why we keep our watches in our pockets or, [as in] the Venerable Semkye lineage, you tack it onto the back of your cap. Again all other jewelry, we have no need to decorate our body because we’re not trying to attract anybody. No need for perfumes or aftershave because we’re not trying to attract anybody. It’s fine to use deodorant, in fact please use deodorant, and get an unscented version. Somebody gave me some unscented and it still smells, but you do your best.

Same with soap, try and use unscented soap whenever possible; sometimes it’s not possible but try and do that. If you are getting glasses, I mean get one glass frame and you just keep using those same frames unless they break or your old lenses don’t fit in them or whatever. But we don’t need to get the latest style in glass frame because that can also become an adornment can’t it? Have you ever noticed, people are really into their glass frames. All that kind of stuff we’re just ignoring. No cosmetics. You can use hand lotion or some kind of lotion if your skin is getting dry, you can use Chapstick, but no lipstick, don’t draw in your eyebrows. I have seen monastics who draw in their eyebrows. Don’t do that.

There’s other monastics who shave their eyebrows. In the Thai tradition, in Thailand they shave their eyebrows, but that is not required in the vinaya. The story I heard why the Thais do that is because some Thai monks were making eyes at women, moving their eyebrows—I’m not sure quite how they do it—so after that, they had to shave their eyebrows.

We wear our robes all the time. The exceptions are unless you are doing manual work where your robes would get totally filthy, in which case it’s disrespectful to the robes, or in which your robes would be a safety hazard. If you’re working around equipment with an engine and your robes could get caught in that engine or something like that, then definitely you would put on work clothes. You see all of us in work clothes when we’re in the forest or working with the tools in the tool shop and stuff like that. You get maroon work clothes—you don’t put on jeans and a nice fashionable in-style sweatshirt or t-shirt, but you just wear maroon clothes and keep it at that.

The only other exception I think is if you’re going through a border check. Like if you’re going to go on pilgrimage in China, then maybe you might want to put on just some maroon pants and not wear your robes out because sometimes the immigration officials in China can make a problem with that. Everywhere else in the world it’s no problem, but in China sometimes it’s better just to really be as incognito as you can, even though you’re not doing anything anyway. The only other time where I wore lay clothes was because my parents were quite upset when I became a nun and didn’t speak to me for quite a while and then my brother got married and they wanted me to come to the wedding. So my teacher told me to wear lay clothes and he said, “You look like California girl.” “Ugh. I don’t want to be California girl.” But he was actually quite wise, because I think if I had landed in the LA international airport with my head shaved and robes my mother probably would have gone hysterical in the middle of the airport.

Except for situations that are definitely something like that, then otherwise there’s no need to have lay clothes or to wear lay clothes. I say this because I remember visiting one Dharma center—this was so strange—the guy who was the director and one of the teachers of the Dharma center was a lay man, married, and there was a Tibetan monk there who was teaching. It was so funny because the lay man wanted to wear robes, even though he was a lay man, so he would wear these maroon skirts and it kind of ups your status if you look for a monk and he wore a white thing which is appropriate for a lay practitioner. I think that sometimes he was wearing a maroon one, which is not appropriate, but he really wanted to look like a sangha member. Meanwhile, the Tibetan monk was putting on lay clothes as he was going to an ESL program and he wanted to become Americanized.

It was like, “Gee, this is really backwards. That’s not the way it should be.” I mean if you have the opportunity to become a monastic, you should treasure your robes and respect your robes and feel privileged to wear them and not just kind of put on something else when you have to go into town. Unless there is some danger, if you are in a situation where there is some danger, then of course.

Within wearing robes, I also noticed that because our robes are dictated, then sometimes people really look for nice quality cloth. We get attached to nice quality cloth. So some people wear like silk shirts or things with a pattern in them or whatever. Although in the Chinese tradition you don’t wear silk and you don’t wear leather. So again, not looking for the best quality cloth and really precious soft shiny cloth. In India, shoes are a big status thing for monastics. Everybody wants Nike shoes; and your jola, your monastic bag, so people now want fancy backpacks. So we have to always keep aware: are we getting something that we carry with us because it’s nice and we use it as a status symbol? Like a really nice backpack, or special shoes or this or that? We should be completely content with whatever shoes we have. Best is not to wear leather and also we don’t wear black and white as they are considered lay people’s colors. It’s okay to have brown shoes or dark blue shoes. But not powder blue shoes or pink shoes, because they really decorate the shoes now with all sorts of different patches and things like that. My personal feeling is that’s not appropriate for a monastic as it’s too easy for your mind to start thinking, “I’m different, I’m better.” But, if course you also have to have shoes that fit your feet properly and if you have foot trouble and need arches or whatever, then you need to get the kind of shoes that work for you and sometimes those may cost more but if it’s the difference between being able to walk and not being able to walk, I think that’s okay.

Did I cover everything about dress? Underwear should be plain and simple, no fancy underwear.

Audience: One coat.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, by vinaya, the monks have three robes, the nuns have five robes. Of those you are allowed to have one set that is your own. Most people have a spare set, so that they can wash what they are wearing. But your spare set, and there is a little ceremony for doing it, either you place it under joint ownership where you share it with somebody else, or you think, “I’m going to give it somebody at a certain time, I’m going to give them this robe. In the meantime, I will use it.” It really cuts out this possessive mind that wants a lot of robes.

I mean you might need maybe three donkas, something like that, because you switch, you have to wash your clothes and we only wash on certain days and things like that. But you don’t need a whole pile of donkas, we don’t need a whole pile of undershirts and we sleep in our underskirt and then a t-shirt, that’s good enough. And we don’t need like… well one jacket, well actually two jackets in case one needs to be washed, and then I need two coats and then I also need a light coat and then I need a sweater—maybe two sweaters, and maybe four sweaters as there’s some sweaters I wear when it’s a little bit cold and some I wear when it’s very cold. And then pretty soon you wind up with a drawer full of various jackets, sweaters, vest and so on and that’s not appropriate. The same thing can go with hats, gloves, scarfs because we need those things. So to really try and keep it simple.

People give us many different things and so even if you think I will need this later, for the time being put it in the closet with all the monastic robes and then if you need it later, if it’s still there you take it. If it’s not still there I’m sure you will find something because we very fortunately don’t suffer from a lack of things and we have a surplus. But we don’t need to keep so many things in our room. You may need some long underwear but you don’t need five pairs of long underwear. Same with socks. And then we try and repair things if something tears we don’t just throw it away and go get a new one—we repair it, and we wear things until they are really old and worn out.

At the time of the Buddha, it was very difficult for them to get robes. That’s one reason, if you look at all of our robes, they’re all patched because you were lucky if you found just scraps of material. They would often go to the cemetery and take the material—the shrouds when they dumped the bodies in the cemetery—they would take the shrouds and dye them and stick them together and they’re stitched together in this pattern because the Buddha one day was standing looking out over the rice fields and noticing the beautiful pattern—and you can still see this in India today—of how the small plots are arranged and so [he] wanted the robes arranged in a certain way.

We definitely don’t need more than one chogyu and more than one namjar. If you ordained in the Chinese tradition and you have your robes from that, then your present Tibetan robes are your namjar and your chogyu. Then the other ones, if you want to keep them, you don’t claim them as your own as then you would possess too many, or we can give them to other people who may need them. That doesn’t happen too often because usually at the ordinations people are very happy to offer the new robes. Did we cover everything there? Anything else?

Change in Name

Then, a change in your name. So we should be addressed by our dharma name. I know when I started out, very few people used their dharma names as nobody could pronounce the Tibetan and we couldn’t remember each other’s names and it’s just so much easier to use the name you knew somebody by. But I think it really does change your feeling when you have a new name, because your old name is just associated with so many different things. I heard somebody say once, why do kids have middle names? Because then you know when you’re really in trouble. Because its true isn’t it, when you’re really in trouble, it’s Cheryl Andrea Greene! It’s like my passport name! So it’s much better actually if we could use our ordained names, because our ordained names also have meanings and it’s inspiring when you reflect on the meaning of your ordained name, it gives you something to live up to in some way.

In terms of legally changing your name, some people do, some people don’t. I think that’s completely up to the individual. I didn’t legally change my name basically because I’m too lazy and it’s too much of a hassle, so I use my legal name for legal things and use Thubten Chodron for everything else and it’s worked out. I know other people who have legally changed their name to their ordination name, so it’s up to you as a person.

Change in Livelihood

Then change in livelihood or occupation. This is a big one. This is very important as Buddhism goes to the West, extremely important. If you look at Buddhism in Asia, the monastics do not work individually for their own personal income. If they’re working, they’re working for the monastery. So for example, some of the monasteries in India will set up guesthouses and they’ll send a few of the monks to manage the guesthouse. Personally speaking, I don’t think that’s a good idea, because I think when monastics are hanging out with tourists and travelers, their minds change. So personally speaking, I wouldn’t choose that. But, they’re doing it. But the money goes to the monastery. When they have these tours, the profits go to the monasteries. Very often people will give them individual offerings, they tend to keep that themselves.

What I’m getting into now is the whole financial structure of the sangha, which I think is quite important, because in old Tibet, you had rich monks and poor monks. If you’ve ever read Geshe Rabten’s autobiography, he had hardly anything to eat because he came from a very poor family and didn’t make friends with all the rich people in town who would give him money. And then there were other people who had benefactors and who ate better and who had better housing. In the monasteries nowadays, what they often do is they try and get individual sponsors for individual monks.

The nuns have been doing it completely differently, which I think is much, much better. And that is instead of the sponsors giving the money directly to the individuals, which again can easily create class differences: those that have benefactors that give more and benefactors who send presents and those who don’t have benefactors or whose benefactors don’t send as much, and then you have some monks that have two or three benefactors, whilst others don’t have any. So this whole thing that comes, I don’t think is a good idea. We were emphasizing before that the monastics should have equal access to resources, and that’s very important for the quality in the sangha. So I think it’s much better when donations are given, that they come to the monastery and that the monastery then supports everybody. That way everybody is supported equally and the money—some people get more offerings, some people get less offerings—it’s used to support everybody in the monastery.

In the US we have to take it into consideration the high cost of health things here. In no other country do you have to pay as much for medical as in this country. It’s really outlandish and outrageous. So what we have is if people have money from before they ordain, this is the way we do it at the Abbey, is they can keep that money but they can only use it for medical and dental expenses. When you are fully ordained, then the monastery pays your health insurance but until you’re fully ordained you have to pay your own. That’s because the monastery wants to know that you’re really in there for the long haul, that you’re really stable in the practice, before covering your health insurance. So if you have funds from before you can keep them but you can only use them for that, or you can use them for travelling to teachings or for making offerings.

If you don’t have enough money for your health expenses, then the monastery, the Abbey will supply them. But if you have savings from before, then you’re expected to use those savings. But you cannot go and buy your own clothes. Usually regarding shoes, we see if there is somebody who wants to offer them and we may need to go out and try them on because otherwise they don’t fit. You can’t go buy a new blanket for yourself, or a new light for your room or a new anything for your room. We have a common supply for toiletries and things. If you have certain skin problems, you can’t use the soap, then when somebody calls and says I want to offer something, then we can give them the name of the kind of soap you need for your skin, or if you need something special. But aside from that, you can’t go out and buy your own stuff because that really creates too much of a class difference. I have been very aware of that as I’ve lived in monastic communities and it doesn’t create a good feeling.

Also, when you can go to the store and buy stuff for yourself, then that consumer minds comes back. It’s like, “Well I just want to get a few artificial flowers for my altar. It’s for my altar! Come on, I can go get [them]. But while I’m at the store, I also see a nice vase for my altar. Not for the community, but my altar. And also at the store, oh! They also sell certain kinds of this or that and I happen to need that as well.” So then it’s very easy to just start buying all sorts of stuff for yourself. The issue of computers come up. At the Abbey we may use the term “my computer” or “so and so’s computer,” but in fact all the computers belong to the Abbey. They are not your individual computer, and if your computer doesn’t work, we get it fixed; if it breaks, and you need a new one, we’ll supply it. But you can’t just go around getting a new computer because you want a new computer.

Some people say, “Well I need a computer for my work, and I need a computer for my study.” Really? The computers have so many gigabytes on them now, why do you need two different computers? Well if you’re doing your study in Gotami house where there is no internet and you have a big computer over here and you can’t carry your big computer over there, then that makes some sense you have a smaller computer you use for your study. But if you do your study where there is internet, you don’t need a separate computer for that. If you’re afraid of using your work computer for study, then you just make two different logons and you logoff your work thing when you’re using your computer for study.

Because otherwise, especially for technology, we always need the latest, newest this and that, don’t we? There’s never any end to it. So the same with cell phones or fancy phones. Maybe we have one or two for the Abbey, which we usually forget to take with us when we need them but we’re trying to remember because sometimes people need to call us when we’re in town. But aside from that, we don’t have our own cell phones, there’s no need for that. There is no need to get the latest this that and the other thing. So let’s remember to try and keep it simple. Of course if your old computer just isn’t working with the new programs or it takes fifteen minutes to turn on, which we did have that problem at one point, then you say something and the Abbey gets you a new computer. But we have to keep the mind wanting possessions to a minimum.

Similarly, in our rooms no family pictures because it breeds attachment, doesn’t it, family pictures? You don’t need pictures of yourself in your room. I have one picture that Traci gave me of me offering tsok to Geshe Jampa Tegchok, I have that. But I’ve seen some, I went to one monk’s place in the US, and the apartment was filled with pictures of him with His Holiness, with this and that. Gave me a certain impression. But we don’t need mementos, we don’t need small decorative objects and souvenirs. All we need in our room is what we use for study, our altar and clothes. I mean I have my office in my room, so I also have paper in my room and stuff like that. I have some khatas. I have tea bags, vitamins, whatever. Really try and keep things as simple as possible. You’ll notice that at the beginning of the practice, your mind will have one definition of simplicity, like we did yesterday and we think, “Oh I’m really living a simple lifestyle.” and that’s because you’ve pared it down. But as you practice more then you realize, “Actually I could live simpler, I could live simpler.”

At the Zen monastery at Mount Shasta, when you’re a postulant and a novice, so I think for six years, you don’t have your own bedroom. You sleep in the meditation hall so there’s absolutely no question of not getting up for meditation—because you sleep in the hall, so you’ve got to get up! There’s a small cabinet in front of your place and you have your robes and toiletries in there. I don’t know if they have their own desks or not, I’m not sure. But what you have is really at a minimum and it’s very good training. I’ve talked to some of the senior monastics and they say what some of the people were saying yesterday, was then when you’re senior and you get your own room, you are trained and so hopefully you’re not as greedy about possessions. But somehow because there is more space and you don’t have your small cabinet, just the possessions start sticking in your room! So again we have to be vigilant about continually taking things out that we don’t really need. If you need a lamp because your eyes are getting strained reading in your room, then you talk to the monastery and we come up with a lamp somewhere. But really keeping it simple as much as possible.

Then the whole thing, livelihood and occupation. The Buddha was very strict—India was an agricultural society at that time, so the monastics could not grow crops, they could not work the fields. The reason for that was twofold: one was it’s too easy to get into an occupation growing food because that’s what everybody did, and second the possibility of killing animals and insects. Also in our precepts, we’re not allowed to buy and sell things, so we can’t do business. Many monasteries do business, at least in the Tibetan community. They have various businesses. And in the West many monasteries have businesses. I think it’s just much cleaner clearer that we live the way the Buddha intended, which is dependent on the kindness of people who give us donations. Because if we do business then our mind becomes a business mind and we’re always looking for how we can get the most money out of something and what new product we can produce, and where we can market it, and what price we’re going to charge, and who we give discounts to. That gets you into a state of mind that is not very productive for your dharma practice.

So at the Abbey, everything is given freely. The reason we do ask some people to give a deposit for programs or to give us a certain amount of dana before a program is so that they commit to come. At the beginning we didn’t ask people to do this, but we had the situation where people would register and then not show up and because they only cancelled at the last minute, there was no time to fill their place with somebody else. So in order to get people to feel more committed to coming, then we said they have to send in a small donation, some donation beforehand. Or for the long programs they send in some dana—not their own dana, you are not paying your own way—but you’re making it possible for the Abbey to have the program. So everybody is getting sponsored on the longer programs like EML, or the winter retreat we ask for that. The reason is to support everybody doing the program. It’s happened that people come and say I want to attend the program, I don’t have any money. We let them come. It’s fine. But we want to make sure people are committed to coming so that places don’t go unused.

I also think that by doing it and not charging, then that gives us the freedom to give and we create virtue by having a mind of generosity that wants to give. Then we hope that people reciprocate. And I’ve seen many Buddhist centers now charge for courses, charge for teachings, some of them pretty hefty amounts, and the Buddha never charged. The Buddha never charged, his disciples never charged. If there were costs it was covered because there were benefactors who made offerings because they saw it was so virtuous to make offerings so that so many people could come hear the teachings. That’s a really beautiful mind and now when His Holiness teaches in India, this is very much the way it’s done. There is usually somebody who invites and they support or a group of people—an organization—invite and they support. They also have an office open during the teachings where everybody can give donations because you have so many people there, so many monastics and as they say a group that’s that big there’s got to be some bodhisattvas! So just giving even a little bit, you create so much merit making contribution to the sangha. Then everybody creates merit, and everybody has this really happy mind.

Whereas if you have to pay for a ticket to go, and you’re getting charged for it, it just doesn’t feel right, it isn’t good. Now I recognize in the West it’s a different seating thing. In India you don’t have seats. So if ten people don’t show up, it’s not like ten seats go wasted and there’s ten people who wanted to come couldn’t. In India everyone just crams in. In the West, if you give out the tickets and then people don’t come, then there’s a lot of seats that go wasted. So I can see the need there to charge a small amount in order to get people to really think about coming and not just grab a whole bunch of tickets when they don’t need them or aren’t going to use them.

And His Holiness, nowadays, he prohibits sponsoring groups to make a profit from having him come. He says any money that is left over should be given away to charity. He himself does not take anything from it, or if they give him money, he then gives it away. His Holiness sponsors the whole Tibetan government in exile I think, by his funds. So again, not to have this mind of doing business, but from our side, just being able to give and then other people’s side being able to give and then everybody feels happy because they are giving. That creates such a different mentality, when everybody is giving freely, when you give the dharma freely, people can come and stay here freely.

That doesn’t mean we let everybody come and stay. There also has to be a screening process, because we’ve had people come and they have absolutely no money and then it doesn’t work out for them here and they don’t have any money to go onto wherever they’re going to go onto and that’s not fair to them. So we make sure that when people come that they always have enough money so that if they have to leave they can get to where they are going. So we have different requirements and so on, but we’re not charging so much a day. People will write us and say, “Can I have a single room and I’m willing to pay more….” Sorry we don’t have any single rooms, and we aren’t charging you to start with! Because part of the thing is to be part of the community and to give freely.

The money from the publications—all the money from my royalties—it goes into a special account—it’s used only for dharma money. We use it for statues, for dharma related activities, for teacher’s airfare when we invite guest teachers. All that money does not get used for food, clothing, this kind of stuff. It’s only for dharma related things. So in the West what you see is a lot of monastics working and I think this is a tragedy. In the beginning it was because the dharma centers were very poor and also because westerners didn’t have much respect for monastics and so didn’t think to support the monastics in the dharma centers. So the monastics had to work either for the dharma center where they got room and board and maybe a small stipend, or many monastics work regular jobs where they have to put on lay clothes and they have their own flats and everything and their car and they put on their robes when they go to the dharma center.

I think this is not a good idea. It’s extremely difficulty to keep your precepts when you’re basically living like a lay person except for putting on your robes and going to the dharma center. Very difficult to keep your precepts. The mind is always worried about money and you have to get a job that pays a certain amount as you have to pay for rent and food and all these things. Then also you can so easily go to the market or the department store and get what you want when you want it. So the mind doesn’t change much, because of the physical condition, it’s very much like it was before you ordained. It’s even gotten so bad that some of my friends who were leading the preparing for ordination class at Tushita told me that one man came one year, he wanted to take ordination with His Holiness and he thought after he ordained he could go back and live in the house with his wife! There was no difference in his mind between being a monastic and being a lay person.

That is what makes the dharma degenerate, I think, when that happens. And so I know the situation in the West is difficult, but I think we have to work to make it better instead of just giving into it and saying, “Okay well I need my flat and my car and my this and my that and my TV and my blah blah blah blah blah blah….” Try and at least live together with other sangha members as it helps your practice to live together with other people. When you live on your own, it’s easy not to wear your robes and spend money when you want. When you at least live with some people it just increases your mindfulness of what you are doing.

What I’ve noticed is, in recent years, even some geshes at the center now tell their ordained students to go out and get a job. That I find really interesting because at the very beginning, the geshes would say only work if you have to, but try and get it so that you can stay at the center and study as much as possible. But then some centers just have enormous costs of rent and the sangha who lives there pays rent and so the geshe tells them also go out and get a job. I find that very difficult. You get some of it from that side, you get some of it from the side of people who want to ordain but they really want to keep the same lifestyle they had before. It’s really a rather sticky situation and everybody’s motivations in all of this is going to be very, very different.

Also it’s quite a different thing: I know some senior monastics who are professors, they live on their own, they have their own car and their own stuff. But, they’ve also been ordained for 30 years and they also know how to live simply and they also keep their precepts very well. That’s a completely different ballgame than someone who is brand new ordained or who has only been ordained three, four, five years who really needs training. Because when you live on your own, you don’t get that training. So very, very difficult. I realize community life is not for everybody, but there’s so many benefits that come from living in a community because you can really see when there is a community, the collection of your merit makes so much more possible.

It’s like, if I want to receive teachings, no teacher—no matter how much money I have—is going to come to teach me alone. I do not have the merit for somebody to teach me alone. “I want to learn Abhisamayalankara for five years, come and teach me alone.” I don’t have that merit. Teachers come when there is a group. So when there is a sangha community or at least a lay dharma center with some sangha members in it, then you are able to get teachings and have more dharma in your life. I think this is something really to think about, it’s like if you’re going to ordain, well why do I want to ordain? Like this man, why do I want to ordain if I’m going to go back and live in the house with my wife and keep my job? What is the purpose? He might say, “Well, I want to keep precepts.” Well then, keep the eight precepts. The eight precepts are perfect for lay people, because you have the five fundamental precepts, plus your third precept becomes celibacy and then you have the three other precepts and if you want to live like a monastic but not be a monastic because you have to… I mean that’s what you do and it’s really praiseworthy I think to take the eight precepts and keep them. Then there’s no confusion about, “Is somebody a monastic, or is somebody a lay person?”

Actually we have a few people affiliated with the Abbey that have taken the eight precepts and live like that and I think it’s wonderful.

Questions and Answers

Any questions about that? I think this whole thing about livelihood and occupation is quite important.

Audience: When I hear this kind of thing and I have my own concerns, the concern for the pure dharma to flourish and sustain in the West because living here I’m more and more convinced that it’s the sangha that can do that. So the quality of the sangha, as far as keeping the dharma pure, can become the bigger issue for the long term.

VTC: I think that’s a big part of it. Because the sangha acts as the example and when you have a community and a place where the sangha lives, then there’s a place where people in society associate with the dharma. There are many lay teachers and its fine to be a lay teacher, but your house with your spouse and your kids does not give the same energy as a monastery. Your house is not going to be the house where people think of when they want to think of virtue being created. So it’s a very different thing.

I really see the difficulty for lay dharma teachers who don’t work another job. It’s very admirable they’ve devoted their life to the dharma, they don’t work another job, but by not working another job, then even though they do dharma talks on dana, the places that give the most dana get those teachers more. A lay teacher always has to think, I have to pay my rent and my kids have to have Nike shoes and go to summer camp, and my spouse and I want to go on vacation and our whole income is dependent on my teaching the dharma and it’s all done on dana basis. So let’s think about where the crowds are going to be biggest and where those people are the most generous and those are the places that I choose to go. Whereas as a monastic, we don’t have to feed a family, we don’t go on vacation, so you don’t have those concerns.

Now it’s true that a lot of our support does come from teaching. But we don’t choose where we go to teach based on who gives us the most dana. We choose where we go to teach based on the sincerity of the people who invite us and the people who really we can see practice and have the most sincere interest in the dharma. Some places we go and the people give a lot of dana and some places we go the people don’t give much dana and it’s okay. The same: some people stay here and they give a lot, some people don’t. It’s okay. Whatever people give we want them to give from their hearts, not because they are doing business.

Audience: From what you said I take it I couldn’t move here with a truck full of stuff?

VTC: Well most everybody who comes and moves here arrives with a truckful of stuff and they offer it all to the community. Yes? So that’s what most people do when they vacate their houses, the furniture comes here. But then you have to be careful because the furniture goes in other people’s rooms and then you look and it’s like, “They stained it! They’re not taking care of my beautiful furniture!” Well it’s not your beautiful furniture anymore!

Audience: You know when the Tibetan nuns were here and I was learning to make momos from them, they kept saying, “Is there a market in Spokane where we can go and sell momos there? It took me a while to see that’s what monastics do in the cities in India, to make food and sell it at teachings. They kept telling me that I should promise to go to the market and set up shop with them. I hope they were kidding. I don’t remember them selling things anyway.

Audience: I don’t remember monastics selling things at teachings, only lay people. Maybe they were joking.

VTC: The monasteries will have restaurants, usually they’ll ask lay people to work in them but I’ve seen monastics work in them too—and guesthouses, and selling carpets, and I don’t know.

Audience: When His Holiness was in Sydney a couple of months ago, a three-day teaching on bodhicitta, there were lots of stalls outside and many of them were run by monastics. They were selling Dharma things…

VTC: But it’s still selling. It’s still selling and it gives… like with our dharma things here we just put them out, people can take them and we hope they give a donation. Which is quite different than being there taking their money, giving them the change.

Audience: A few years ago I met a fellow who was a monk, I think he was living in Spain and he had to work as a photographer because he didn’t live close to the center. But I guess he had to drive to the center a lot and he was constantly changing his cloths. And then I thought, what does his neighbors think about what a monastic is? Some days he’s a lay person taking photographs and sometimes he’s looking like a monk. So that’s really hard for lay people too.

VTC: Yes, it is. It is very hard for lay people when they don’t know what you are. Serkong Rinpoche used the example of a bat. For a bat, when people are putting out mouse traps then the bat says, “I’m not a mouse, I’m not a mouse, I’m a bird.” And when people are trapping birds, then the bat says, “I’m not a bird, I’m not a bird, I’m a mouse!” So you’re not quite sure what you are, like a chameleon. It’s not so good for the mind.

You can really see what we are doing involves an incredible process of education because people come here they have no idea what a monastic is, how monastics live, anything about it. So we’ve really had to teach them and explain what dana means, and the economy of generosity and explain some of the etiquette and different things like that. But what we’ve really seen is how the lay supporters are really generating sincere respect for the sangha, not for us as individuals because respect for the sangha is not for the individual. It has nothing to do with you as an individual, so if somebody offers you respect because you are in robes, don’t start getting all inflated. It has nothing to do with you as an individual. It has to do with you wearing the Buddha’s robes, and those robes are inspiring and those robes give people a visualization of what they can become, and of people’s potential in general. They give people a vision of ethical conduct and of people trying to develop love, compassion, joy and equanimity.

So we find as we’re going along that people are developing that kind of association with the robes. But really, especially if you go to Asia—not in the Tibetan society, but if you go to Taiwan or Singapore—people will bow to you because you are wearing robes. You always think, “There’s the buddha in my heart and the people are bowing to the buddha. It has nothing to do with me.” But you really see how when people are doing that, you develop this sense of, “Wow, their minds are so virtuous.” They have this incredible faith in the triple gem, and this cloth is representing that to them and when they’re bowing, their faith in the triple gem is being expressed and it’s so beautiful to think about that. So you really rejoice at their merit.

Same with if they give you an offering, it has nothing to do with you. It has to do with the robes, with the sangha, with keeping the precepts that the buddha set down. So you see people’s virtuous minds and there they are giving money or whatever and you think, “What did I do? I’m not doing anything.” Then you think, “Well my part of the thing is I’ve got to keep my precepts well and I’ve got to do my practice well. So I can’t oversleep, and I can’t just kind of indulge in my attachments, I really have to work with my mind because I’m wearing those robes and that’s what those robes are indicating.”

It’s not a thing of guilt-tripping ourselves or pushing ourselves, it’s a thing of growing into an awareness of your potential to be a beneficial influence to people. Simply by wearing the robes, by doing your practice, by how you carry yourself, by how you talk to other people. Then of course all of that depends on how you really work with your own mind. If you are monastic and you’re out in public and you’re getting angry, it gives people a certain visualization. Or you’re hanging out in the movie theaters, it gives people a certain visualization.

We will continue with this tomorrow. But I think these are important topics to constantly remind ourselves so that we get some kind of idea really about what monastic life is all about. And because we’re just creating it here let’s try and create it in a really good way. Instead of creating it in the lowest common denominator, let’s try and create it in a really excellent way.

Audience: The geshes often, they don’t screen people so directly. I have seen that, people ordain and they do crazy things. They don’t have the experience, they don’t have a sangha [where they can] learn from seniors and so on and then disrobe. And then they take the robes again and all these very confusing things for lay people. The geshes are doing it because they are thinking one day ordained is more virtuous than another day or..?

VTC: This is part of a cultural difference. The geshes, first of all, think that it’s more virtue keeping the precepts one day in this degenerate age than it is keeping them for your entire lifetime at the time of the Buddha. Second of all, they have the idea as this is the way it was in old Tibet, in old Tibet you need a lot of people to do the study program where you’re doing debate and discussion. You need a lot of people and so their idea is you ordain a lot of people, so you can do that program. Then also, because they take so many people in when they’re children, you don’t really know what they’re going to grow up to be. The idea is you take in a lot of people and then through that the ones who are really suitable and are good scholars in something, they will rise and you will see them—and then the rest will serve the monastery or disrobe and go and sell sweaters or whatever. So that’s their way of thinking and then also when they’re in the West, they think, “Oh well somebody came and asked me for ordination, they’re going to be very upset if I say no so I should say yes.” But then, it gets really sticky as you noted: people are in robes and out of robes and people with very severe mental problems get ordained and then they don’t act properly. It really makes the lay people lose respect for the sangha as an institution, which is really unfortunate when that happens.

But the geshes so many of them don’t speak our own western languages, and whenever anybody goes in front of a geshe they always act really well, so it looks like the person is fine even though they could be totally psychotic—and I’ve seen this happen. Whenever we’ve tried to establish it, when there is a large organization, so that the westerners do the screening, the geshes don’t like that. They like to ordain people and then they send them to the westerners and we have to live with them. But that doesn’t work in a monastery. If you have a monastery, you’re the ones who have to be able to discern who comes and lives with you and who ordains. So when the geshes don’t do that, that’s difficult. Also, technically speaking according to vinaya, if you ordain somebody you should help them with their support at least with simple accommodation, food and so on. And for most of the geshes who ordain westerners, most of their dana goes back to their own communities—the Tibetan communities in exile or in Tibet. If anything, they expect the westerners to help them raise money. So it’s difficult.

Audience: I get the impression they have more priorities towards the teachings too, philosophically teachings, than the vinaya teachings.

VTC: Yes. The Tibetans have this joke they think it’s completely hilarious, and I don’t think it’s so funny but anyway. Because when you do your studies, the vinaya comes at the end. Theoretically the idea is you study prajnaparamita, you study emptiness, you study logic, you study abhidharma, then through all that study of course you want to become a monastic to really practice, so vinaya comes at the end. The reality is, you take ordination first and then you go study all those topics in the Tibetan monasteries. As lay people you really can’t go into the monasteries. The monasteries don’t have very many lay disciples, if any at all. So then the Tibetans say, “Oh when you have your precepts, then you don’t study vinaya because that’s at the beginning of your training, you have your precepts but you don’t study vinaya because that’s an advanced class. And by the time you get to the vinaya, you don’t have your precepts any more.”

So they go, “Hahahahaha,” and I go, “Ohohohohoh [holds head]. Whereas in the Theravada countries and also in Chinese Buddhism, at the beginning you learn vinaya. I think that’s quite helpful.

Audience: Just a comment about that is that I’ve seen a couple of curricula at different lineages monasteries that aren’t Gelugpa and they do put vinaya first in the first couple of years.

VTC: That’s good.

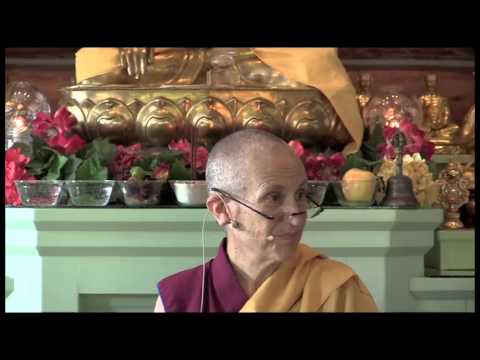

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.