How precious is monastic community

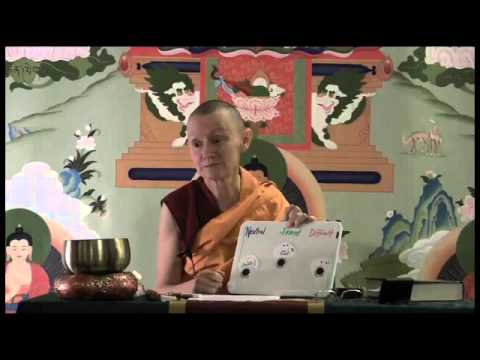

Ruby Pan (now Venerable Damcho) had the good fortune to travel with Venerable Chodron in Asia as her attendant on two occasions in 2012. She shares her reflections on the monastic communities they encountered on their travels.

If the followers of my teachings, the Buddhadharma, who wear even four inches of robe don’t get food, then my having achieved Buddhahood has betrayed sentient beings and may I not receive enlightenment.

—Compassionate White Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni Buddha

It has been an eye-opening experience traveling with Venerable Chodron in Asia, first on her teaching tour in Indonesia in May 2012, and now to attend teachings by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in India from November to December 2012. We are constantly surrounded by the kindness of sentient beings who go out of the way to make sure that Venerable Chodron is well cared for, because they respect her as a Dharma teacher.

I am astounded that more than 2,500 years later, a confused sentient being like myself is still benefiting from the kindness of the Buddha, who taught the pure Dharma, which was passed on through an unbroken lineage to our kind teacher Venerable Chodron. It is because Venerable Chodron practices the Dharma purely that she can teach it from the heart, and in return, people are moved by the Dharma and respond with gratitude and generosity both to her and Sravasti Abbey.

What strikes me repeatedly on these travels is how a place like Sravasti Abbey is incredibly rare, for the following reasons:

- We have a qualified Mahayana spiritual mentor who is a permanent resident at the Abbey;

- There are bhikshunis and elders in the community who practice with great effort and sincerity, maintain community rules, and are happy to guide newer members;

- There are practical structures in place to support community life, such as the schedule, community meetings, regular discussion groups, and training in non-violent communication;

- There is a balance between practice, study, and offering service in the schedule;

- The Abbey runs on an economy of generosity, and aside from maintaining personal health insurance, room and board is provided for all monastics at the Abbey;

- The Abbey is located in a rural environment conducive to meditation and practice, but remains socially engaged and connected to lay communities in the immediate neighborhood, and to Buddhist communities worldwide through the website, Venerable Chodron’s books, and teaching tours.

These are not conditions to take for granted. In Indonesia, the Buddhist Sangha declined for a period of time and was only revived in the 1970s, so the number of nuns is still small, relative to the needs of a Buddhist population spread across an archipelago of islands. As such, there are no established nuns’ communities, and nuns are dispersed in Dharma centers across Indonesia, where they may live alone or in the company of one or two other nuns. Often, the nuns are busy with administrative work, organizing pujas for the deceased, and fund-raising, such that they do not have time for personal study and retreat.

Fortunately, the monks and lay people of Ekayana Buddhist Centre, who organized Venerable Chodron’s teachings in Indonesia, were aware of this problem and requested her to lead a retreat for nuns near the holy site of Borobodur, with limited spaces for lay people.

The retreat saw 27 nuns from different Buddhist traditions flying in from all around Indonesia and practicing together for the first time. It was clear that it was meaningful and important for the nuns to be in community. The organizers requested Venerable Chodron to lead discussion groups for the nuns, during which they spoke openly about their struggles—feeling overwhelmed by running a Dharma centre and attending to lay peoples’ requests; feeling upset when their teacher was too busy to give them teachings; becoming bored with their practice over the years. Being able to share these concerns with fellow monastics and receive empathy, encouragement, and Dharma advice provided solace. From the discussion groups, it became clear to me that it is not only rare to ordain, but also incredibly rare to live in a monastic community and environment that is conducive for Dharma practice.

In Dharamsala, India, we met with two nuns’ communities that had been intentionally established despite difficulties. Again, I saw how being in community is key to supporting monastic life.

The Dharmadatta nuns’ community is made up of four Western nuns who share two floors in a rented building. They divide their chores and have meals together, which fosters a sense of community spirit. Sharing a space has also allowed them to establish a communal meditation room, from which they record and broadcast Dharma teachings online. These may seem like small things, but I think they make a world of difference compared to living alone in a rented room in the middle of a city, worrying about whether your savings can sustain you. If your mind is strong, external circumstances wouldn’t matter, but for the fledgling monastic, I think it helps to have a structure to guide your daily life and to have support from elder monastics who have trodden the same path.

We also visited Thosamling Institute, a center for nuns and laywomen situated amidst idyllic rice fields, set against a stunning backdrop of mountains. Venerable Sangmo, who started the centre single-handedly, seems to be the only permanent resident, while other nuns are resident for periods of time, or visit on the weekends to escape the busyness of McCleod Ganj. At a discussion group with the nuns and laywomen, Venerable Chodron highlighted the difficulties that Venerable Sangmo went through to establish the center, which few people seemed to be aware of. I think every Dharma center and monastery has stories like this, which are useful to hear because they help us appreciate all the causes and conditions that have to be in place to establish a space where the Dharma can flourish. Now, Venerable Sangmo is worried about the future of Thosamling Institute as she grows old, as there is no stable sangha community there, in part due to the difficulties of obtaining long-term visas in India. Establishing a center is difficult enough, much less ensuring that it continues to grow with subsequent generations.

One issue that arose in Venerable Chodron’s discussions with both communities in Dharamsala was whether bhikshuni ordination would be established in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. This was especially pertinent because Venerable Chodron had arrived in India in October to attend a conference organized by the Tibetan Department of Religion and Culture, where monastics were gathered to share research on this issue. It struck me that Western-educated nuns ordained in the Tibetan tradition are in a particularly difficult position, as we grow up with certain ideas about feminism and gender equality, which are challenged head-on in a tradition where higher ordination is not available for women.

Venerable Chodron has clearly worked with these struggles, and offered thought transformation tips to the nuns. First, she noted that even though Westerners are excluded from traditional Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, this also means that they have greater freedom. For instance, it is possible for the nuns at Sravasti Abbey to take higher ordination in the Dharmaguptaka lineage in Taiwan.

Venerable Chodron also stressed that women must support women. Instead of feeling resigned about the situation, we must keep working to open doors for fellow female practitioners. In this light, I think it is important for women to take Bhikshuni ordination. Venerable Chodron emphasized that it is not about “advancing your status,” but about taking on leadership and responsibility—to receive, learn and keep the precepts well, so as to pass them on to future generations of monastics.

Soon after arriving in Mundgod, India, where we will stay until the end of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings in December, we visited Jangchub Choeling Nunnery, where there are close to 300 nuns from Tibet and the Himalayan Regions. We were moved to hear stories about how the Tibetan nuns still have to risk life and limb to cross mountains by foot, traveling by torch at night and hiding from Chinese patrols in the day, in order to reach the nunnery. This year, only three nuns made it even though 20 were supposed to arrive from Tibet. Venerable Chodron was glad to see that the conditions for the nuns has improved—Venerable Jampa Tsoedron and the Tibetan Centre in Hamburg have been instrumental in providing fund-raising support to the nunnery. There is now enough housing for all the nuns, which did not use to be the case, and the nuns are now able to go for examinations to receive Geshe-ma degrees. It was also wonderful to see the Abbess who established the nunnery being cared for by all the nuns in her old age. One of the elder nuns joked that the Abbess did not need to worry about not having children to care for her, but if you think about it, it is probably easier to raise a family than to establish and maintain a nunnery with 300 nuns!

We are tremendously fortunate that Venerable Chodron decided to establish Sravasti Abbey. When I hear about how she traveled from one Dharma center to another for many years based on her teacher’s instructions, often not knowing where she would live next, I think community life is the easier option for a young monastic. I feel very fortunate to join the Abbey at a time when there is a stable monastic community, when most of the hard work of getting the Abbey off the ground has already been done—those of us who come to the Abbey now probably don’t know half of the difficulties that the community went through over the past 9 years. Also, I am grateful to all the lay people who believed in Venerable Chodron’s vision, and gave generously to her over the years.

Venerable Chodron gives everything she receives to the Abbey, so that present and future monastics can practice without worrying about necessities. Having benefited from the kindness of our teachers, fellow practitioners, and all sentient beings, we owe it to them to practice sincerely and establish the Dharma in our minds, for the benefit of countless sentient beings in all future lives until we achieve Awakening.

Venerable Thubten Damcho

Ven. Damcho (Ruby Xuequn Pan) met the Dharma through the Buddhist Students’ Group at Princeton University. After graduating in 2006, she returned to Singapore and took refuge at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See (KMSPKS) Monastery in 2007, where she served as a Sunday School teacher. Struck by the aspiration to ordain, she attended a novitiate retreat in the Theravada tradition in 2007, and attended an 8-Precepts retreat in Bodhgaya and a Nyung Ne retreat in Kathmandu in 2008. Inspired after meeting Ven. Chodron in Singapore in 2008 and attending the one-month course at Kopan Monastery in 2009, Ven. Damcho visited Sravasti Abbey for 2 weeks in 2010. She was shocked to discover that monastics did not live in blissful retreat, but worked extremely hard! Confused about her aspirations, she took refuge in her job in the Singapore civil service, where she served as a high school English teacher and a public policy analyst. Offering service as Ven. Chodron’s attendant in Indonesia in 2012 was a wake-up call. After attending the Exploring Monastic Life Program, Ven. Damcho quickly moved to the Abbey to train as an Anagarika in December 2012. She ordained on October 2, 2013 and is the Abbey’s current video manager. Ven. Damcho also manages Ven. Chodron’s schedule and website, helps with editing and publicity for Venerable’s books, and supports the care of the forest and vegetable garden.