Dharma masala

Kabir Saxena discusses his diverse religious background—Hindu on this father's side and Protestant on his mother's—and how they nourished him as a child and continue to do so as an adult. He shows how we can build upon our childhood religious contacts, taking their positive aspirations and practices into the spiritual path we follow as we mature. In this way our path is enriched, yet we respect each faith that contributed to it, without indiscriminately mixing them together into a religious soup.

If, as His Holiness the Dalai Lama has remarked, the world’s religions are like various nourishing foods, then I was born into a family matrix resembling a veritable feast, the tastes of which have permeated my life hitherto.

However, neither parent was religious in any overt sense. My English mother would have called herself agnostic. My grandfather, perhaps in reaction to his father, a renowned preacher (of whom more in a moment) was, broadly speaking, a humanist. As a child I remember playing table tennis with him on the dining room table in his Golders Green home (a Jewish neighborhood of London), while he held forth on one of his favorite themes—the awful crimes against humanity perpetrated in the name of religion. While the ping-pong ball was noisily struck back and forth Grandpa would entertain me with descriptions of real and alleged burnings, fryings, hotplates and other sundry acts of former religious personages and inquisitions. He would always, however, remind me later that, in fact, he loved the authorized version of the Bible for its magnificent, moving language. This was not the sole means of moving the heart at Grandpa’s. I would consider the evenings spent with him listening to Mozart and Beethoven on BBC Radio 3 as religious in the sense of aiding the process of linking up again (“re-ligare”) with a source of strength and joy within. These are perhaps the earliest memories I have of transcendent feeling (albeit at a far lower rung of experience than that of the yogis or saints, but very significant and nurturing nonetheless).

My great-grandfather was the Rev. Walter Walsh, whose photos and voluminous sermons dotted Grandpa’s shelves, as they do now our living room in a New Delhi suburb. Brought up in a strict Scottish Presbyterian tradition, it took him years of painful reevaluation and logical reasoning at university before he felt he had emerged from the dark tunnel of his rigid doctrinal cocoon of an upbringing. He went on to become the foremost radical preacher in Dundee at the Gilfillan church, which, to this day I am told, maintains a healthy alternative line in sermons. Rev. Walsh communicated with many of the great religious and philosophical thinkers of his time, including Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi in India. His weekly sermons were liberally sprinkled with quotations from all the major religions as well as from mystical traditions like Sufism. He founded the Free Religious Movement for World Religion and World Brotherhood, and it seems as though he aroused some interest in India: “I have many eager friends in India who are palpitating with earnestness and self-devotion towards the same great cause of universal religion and universal brotherhood,” he wrote.

In a series of moving lectures given in the first decade of this century, Rev. Walsh feels “the religion of the future will not be sectarian, but universal.” A noble hope, that often seems a forlorn one, except that there is hope contained in the statement he then makes, which resonates well with the hopes and needs of today, that “for the religion of Jesus we must now substitute the religion of humanity.” What the world wants, states Rev. Walsh, is “the union of all who love in the service of all who suffer.” How wonderful it would have been had the altruistic Reverend undertaken a journey to the Potala with Younghusband’s expedition. My mother would then have brought me up a Buddhist.

I have never undertaken an extensive reading of my great-grandfather’s works but knew enough about him by the time I was in my mid-teens to benefit from his example of a man of God who in his inner process never forgot the service of humanity. It means a lot to me today when, at the age of 42, I sit and write in the grounds of the former Senior Tutor to His Holiness the fourteenth Dalai Lama above the Indian hill station of Dharamsala and ponder the value of the Tibetan Buddhist thought transformation teachings with their emphasis on courageous great compassion.1

This crucible of my youth didn’t consist only of a Western radical Christianity tempered with a universal humanism. I am half Indian by birth and my Indian father’s clan provided another fascinating complex of ingredients that were to prove by no means insubstantial in their effect on my mental development.

My father was a staunch socialist with an intellectual’s antipathy towards the machinations of priesthoods. He changed later, but as I grew up with him, the atheist in him was still strong. Dad’s father was in the Ministry of Defense under the British and then in Independent India. What I remember of him is his increasing visual impairment and incessant recitation of mantras on his rosary. Like Tiresias, outer loss of vision was compensated by an inner fortitude that, for me at least, appeared calm, strong and at peace with the often tempestuous goings on of the Saxena household. If he were the quiet contemplative, grandmother was the pujari, or ritual priestess of the household. In between scoldings, complaints and many small acts of kindness, she would do her daily puja at her shrine in the kitchen. In India, as no doubt elsewhere, the spiritual and food and beverage departments often coincide. (pahle payt puja, first the offering to the stomach, as we say in India.) Only after that follows puja, or offering, to the deity. After all, didn’t Gautama have to eat delicious rice pudding before he could meditate powerfully enough to attain Awakening?

I don’t suppose for a moment that these are in any way dramatic influences on my spiritual development. And yet this context of practice, however unsophisticated and workaday, did, I believe, leave its leavening imprint. To say that the ritual actions and altar of my grandmother generated a sense of the sacred within me may not be an exaggeration. I was not yet ten years old, very impressionistic, and it was important for me to ascertain that adults didn’t just talk, eat, look after us and issue reprimands but also had some kind of communication with an unseen world that wasn’t totally explicable through its symbols. The gaudy posters of gods and goddesses took on a fascination for me, an almost erotic quality that I recall with amused interest.

Festivals never were as important for my family as for many others in India, but were observed nevertheless, with varying degrees of enthusiasm by all the family. During visits to the Kali statues in the local market-place at Dussehra, I found that there were beings with more heads and limbs than I had and this has proved an invaluable piece of information since!

I also learned that dissent and non-conformity are as acceptable as belief. Father’s elder brother had books of all types, and nourished his spirit through poetry. How well I remembered him berating me: “What, you don’t know the poetry of Tennyson!” Another uncle was outright disdainful of all matters religious; another was an exemplar of generosity, bringing sweet jalebis home more evenings than not.

One aunt was into Aurobindo and both she and another aunt were into duty and the fulfilling of obligations that were considered “karmic” and therefore unavoidable, however distasteful or unfortunate they appeared to me.

From my teens onwards I was always reminded of my namesake, the great poet and mystic Sant Kabir (1440-1518), whose works have touched the hearts of millions of Indians, both Hindu and Muslim. Friends and guests as well as family would recite couplets that illustrated the sensitive and observant humanity of Kabir as well as his ecstatic experience of a personal god within that was not dependent upon temple or mosque for its realization. Kabir’s tolerance, as well as his critique of the spiritual sloth and hypocrisy, left their marks and echoed to some extent the sentiments of Rev. Walsh. I love the story of Kabir’s death. It’s said that Hindus and Muslims were arguing over how the body should be given its last rites. When they removed the shroud they found the body transformed into flowers which they evenly divided up and disposed of each according to their religious tenets.

Throughout my early adulthood I experienced again and again how poetic and musical experience in the Indian tradition was infused with a deep sense of the sacred, a process that could stop the chattering mind and awaken the heart; induce a special feeling and sense of participation in life that is hard to describe in words. The Buddhist chanting I so relish now has its antecedents for me in the hymn-singing at school in England, where the magnificent organ produced sounds that stirred and reached parts of oneself that daily routine left untouched. When, through a surfeit of adolescent rebelliousness and self-importance, I stopped joining in the congregation’s vocal invocation of God’s mystery and glory, I was left the poorer, at a time when the healing power of sound would have helped restore my wounded and damaged teenage self, as it heals me now.

The transformational quality of sacred sound was for me brought home in a very powerful way on an OXFAM-organized drought relief project in central India in 1980. A local village mukhiya, or chief, was known as a bit of a scoundrel and I disliked him intensely. I was inspired to sponsor a recitation of the holy Ramayana during the festival days commemorating Rama’s holy deeds and was happily surprised to witness the effect the chanting had on the participants and myself. The mukhiya sang with great gusto and devotion. He himself appeared to change, as did my perception of him, in a kind of blessed moment when the objections of the mind were drowned in the elevated feelings of the yearning heart.

All this said, however, I am certain that the most powerful formative influence on my later mental development and adoption of Buddhism was the Bhagavad Gita, (c. 500 B.C.), of the Hindu tradition, a crowning ornament of Sanskrit literature and inspirer of countless generations of Hindus and Westerners alike. Henry David Thoreau in his Walden had this to say of it: “In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita… in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial.” Most of its main themes inspired me in my teens and have proved to be of utmost import to me as a so-called Buddhist at the end of the twentieth century. These themes are as follows: yoga as harmony, a balance between extremes; the weight given to tolerance, as in the idea that all paths lead ultimately to God, salvation; joy as an attribute of the true spiritual path; the supremacy of the path of detached action without concern for a reward; the central importance of a serene wisdom beyond the violence of the senses; and last, salvation through the wisdom of reason.

I find most of these themes reflected in the other classic that informed my formative years—the Dhammapada—as well as in much of the Dalai Lama’s writings. Take reason, a factor that attracted many, including myself, to the teachings of the Buddha. The Gita says,2 “Greater than the mind is buddhi, reason.” For those who think Buddhism is largely ritual and devotion, His Holiness sets the record straight: “At the heart of Buddhism and in particular at the heart of the Great Vehicle, great importance is placed on analytical reasoning.”3

The serene wisdom, joy and control over the senses extolled in the Gita were clearly manifested in my first serious Buddhist teachers. Furthermore, the sublime thought of bodhicitta—the awakened heart striving for complete enlightenment for the benefit of all suffering beings—was a marvelous progression from and expansion of a beautiful line in the Gita: “(The yogi) sees himself in the heart of all beings and sees all beings in his heart.”4 Such a being, according to the Upanishads, “loses all fear.”5 These kinds of spiritual insights, though only “paper insights,” still had the power to feed my thirsting teenage mind as they do today, except that now I read mostly Buddhist literature and hear teachings from Buddhist masters alone. Is this narrow-minded? Not, I think, according to the broad-minded vision of the Gita: “For many are the paths of man but they all in the end come to me.”6

Buddhists are often annoyed at what they see as Hindu inclusivism in the Hindu notion, for example, that Buddha was the ninth avatar or incarnation of Vishnu and therefore was a Hindu. So what if Hindus say this? Doesn’t it actually lead to greater harmony and acceptance of Buddhism by Hindus? Perhaps if they didn’t feel this way there’d be no room in India for Buddhism and I would be writing this in the mountains of New Mexico rather than in the Himalayan foothills. So I actually am growing fonder of this approach of the Gita. It is a little like Buddhists showing respect and appreciation for Jesus Christ by regarding him as a great bodhisattva, a being inexorably headed towards complete Buddhahood for the sake of all beings.

Some writers7 have powerfully attacked aspects of Hindu belief as representing a “defect of vision,” a “negative self-absorption,” Hindus as being fascinated by “the stupor of meditation,” and the religion itself as the “spiritual solace of a conquered people.”8 There is much in what such writers say, but I myself have not been influenced by these narcissistic, rigid streams within the modern practice of Hinduism and have been well-guarded against the stupor of meditation by the excellent advice of my highly-qualified spiritual friends and teachers.

However, many people question the validity and ability of religion to respond creatively to the challenges of a world that our grandfathers and grandmothers would hardly recognize. A good friend of mine recently wrote to me, concerned that Buddhism still represented for him an “escape from involvement.” He wrote this, despite many years of receiving my letters that detailed our extensive work in the larger community and in our inner community, which was peopled by a multitude of troublesome and helpful characters. Obviously the prejudice runs deep. Why? There’s a lack of skillful and meaningful spiritual instruction worldwide—and almost no scope for mind-transforming practice—the kind of inner work that produces the likes of Milarepa, the Kadampa masters,9 and some great teachers in this very century. Even where valid spiritual literature exists, it tends to fossilize on bookshelves in the absence of authentic guides who can show us how to actualize it in our lives. This is where I feel very fortunate in having met the Buddhist tradition and its exponents—here were living embodiments of what the Buddhist scriptures spoke of. By contrast, I never met a living embodiment of the Gita from the Hindu tradition until much later when I encountered Baba Amte and his selfless work for the leprosy-affected,10 and Baba wouldn’t call himself a religious person, just a humble servant of others who finds it painful that people can find so much interest “in the ruins of old buildings, but not in the ruins of men.” It is of great importance to me that His Holiness the Dalai Lama met Baba Amte at the latter’s project in the early 1990s. I see it as a vindication of the union of the good heart and consecrated action that has always been the balm for this suffering world. Both the Dalai Lama and Baba Amte have emerged spiritually victorious in unbelievably adverse circumstances. They are my icons, the courageous examples I aspire to emulate in my life, beings who fully manifest the meaning of these inspiring words of St. John of the Cross with which I wish to conclude: “Never fail, whatever may befall you, be it good or evil, to keep your heart quiet and calm in the tenderness of love.”11

See especially Lightening the Heart, Awakening the Mind, His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Harper Collins, 1995 ↩

The Bhagavad Gita: 3:42. Translated by Juan Mascaro, Penguin, 1962. ↩

Beyond Dogma, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Rupa & Co., 1997. ↩

Bhagavad Gita: 6:29. ↩

The Upanishads, pg. 49, translated by Juan Mascaro, Penguin, 1985. ↩

Gita: 4:11. ↩

See especially V. S. Naipaul’s India: A Wounded Civilization for an interesting, if controversial, discussion of Hinduism’s atrophying and progress-hindering effects. Penguin. ↩

All quotes from Naipaul, op. cit. ↩

Great ascetic practitioners of the eleventh and twelfth centuries whose pithy instructions embody the essence of the mind training or thought-transformation teachings of Mahayana Buddhism. ↩

Baba Amte’s main project, Anandwan, is approximately one hundred kilometers south of Nagpur near the town of Warora in India’s Maharashtra state. Described by His Holiness the Dalai Lama as “practical compassion, real transformation; the proper way to develop India.” ↩

From his Spiritual Letters, quoted in Mascaro, Upanishads, op. cit., pg. 37. ↩

Kabir Saxena

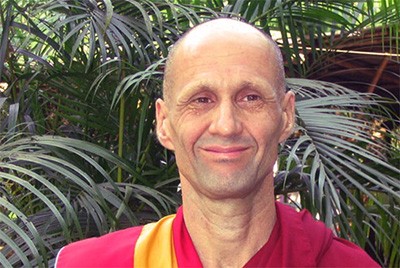

Venerable Kabir Saxena (Venerable Sumati), was born to an English mother and an Indian father and raised in both Delhi and London, attending Oxford University. He met his main teachers Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche in 1979 and has been living and working in FPMT Centres almost ever since, including helping to establish Root Institute and serving as its Director for many years, before being ordained as a monk in 2002. He is currently the Spiritual Programme Coordinator at Tushita Delhi. Ven Kabir has been teaching Buddhism to Westerners and Indians in India and Nepal since 1988 and presents the Dharma in an appropriately humourous and meaningful way for modern students. (Photo and bio courtesy of Tushita Meditation Centre)