Renunciation and simplicity

Report on the 10th annual gathering of Western Buddhist monastics, held at Land of Medicine Buddha in Soquel, California, from September 27 to October 1, 2004.

Renunciation and simplicity are challenging topics for a materialistic, status-conscious culture such as ours, where “more is better.” But this is precisely the topic we dove into at the Tenth Annual Buddhist Monastic Conference, held at Land of Medicine Buddha (LMB), Sept. 27 to Oct. 1. During these days, thirty Western monastics from the Thai and Sri Lankan Theravadin, Japanese and Vietnamese Zen, Chinese Ch’an, and Tibetan Buddhist traditions discussed topics such as: What is the relationship between renunciation and simplicity? What changes occurred for us individually as we went from greed to need and as we transitioned from indulgence to sustenance? What is the value of simplicity? While living a simple lifestyle, how do we handle the complexity of the world? Of our minds? Of living in community with others, be that in a monastery or in society as a whole?

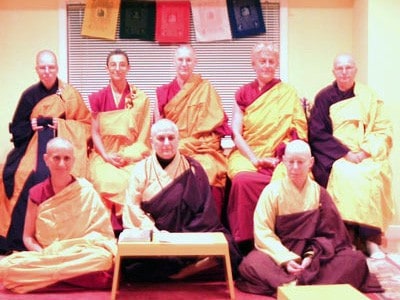

Five presenters shared their thoughts on these and other topics: Rev. Kusala from International Buddhist Meditation Center, Rev. Meian from Shasta Abbey, Bhikshuni Heng Ch’ih from City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Viradhammo Bhikkhu, and Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron from Sravasti Abbey. After the presentation to the large group, we broke into smaller discussion groups where we shared personal reflections, doctrinal perspectives, empathy, and laughter. One afternoon we went to the beach near Santa Cruz, California, to do the practice of Water Charity to the hungry ghosts. Can you imagine the display of our various colored robes against the blue ocean and white sand? That same multi-colored display was apparent as the bhikshus and bhikshunis did our Posadha ceremonies—the bi-monthly confession and restoration of precepts—and when we lined the road to greet Choden Rinpoche, a Tibetan master, as he arrived at LMB.

One evening we had a “town square” meeting with members of the larger Buddhist community where we fielded questions about our monastic practice and communities. At that time, the director of Land of Medicine Buddha commented that hosting the conference was a tremendous blessing for the center. I believe such a gathering is a blessing for society-at-large as well: It is a blessing to know that in a world where people quarrel and kill each other in the name of religion, monastics from various Buddhist traditions gather in harmony for the purpose of supporting each other in spiritual practice and creating peace. Since many of the participants have attended this conference over the years, our friendship continues to deepen, and the bonds among our monastic communities strengthen.

While summarizing the rich discussions on renunciation and simplicity cannot be done in a short article, sharing a few points is helpful:

- The sangha (monastics) works all the time, but our work is not linked to the market place economy. For us, time is more important than money; we don’t seek happiness from having possessions, romantic relationships, or societal status, but spend our time on internal cultivation and benefiting others. Sangha lifestyle is 24-7, and our “job” is to become enlightened.

- Renunciation doesn’t mean to give up happiness, but to give up suffering and its causes and to cultivate genuine satisfaction and joy. Since cyclic existence continues without break, we aspire to make our Dharma practice just as consistent. We “relax” in a different way from laypeople, because we have chosen to abstain from what is usually called “fun.”

- Each of the three Higher Trainings involves a level of renunciation. The Higher Training in Ethical Discipline involves giving up destructive actions of body and speech; the Higher Training in Concentration necessitates abandoning distractions; and the Higher Training in Wisdom relinquishes mistaken views and grasping at self. True simplicity is to let go of self.

- While as monastics, we voluntarily give up certain things according to our precepts. In addition, we may choose to give up other things for a while as a training. For example, by living in community, we explore what happens to our minds when we don’t have our own space, our favorite food, or our own vehicle. We watch what our mind does when we give up our preferences and voluminous opinions and follow the abbot or abbess’s instructions. We take as a practice letting go of the duality between having our own time to do what we want and participating in community practice sessions and work periods. We grow by renouncing having our own way when we live in a community in which decisions are made either by consensus or in some cases by majority vote.

- While renunciation often has the implication of giving up, it also involves keeping. We keep precepts; we commit ourselves to attaining enlightenment. We preserve key aspects of the precious monastic tradition that has played a major role in passing the Buddha’s teachings from one generation to the next for over 2,500 years. May these teachings spread in our world and bring peace in the hearts and lives of all beings through our practice of them.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.