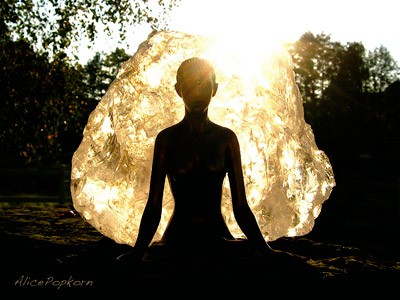

Celebration of Buddha’s enlightenment

By V. R.

In 1997 V. R. arrived at San Quentin State Prison. One year later he wrote a proposal to bring the Buddhadharma within its walls. Two Soto Zen Dharma teachers from Green Gulch Zen Farms responded to his plea. Last December the prison sangha celebrated the Buddha’s Enlightenment by offering a social to the Green Gulch community in appreciation for their help. V. R. delivered the following statement in which he recalls two seminal events in his life: the night he committed violence and the night he discovered Buddhism.

My name is V. R. My Dharma name is Jin Ryu Ei Shu (Benevolent Dragon Endless). I want to thank everyone for taking the time out of your busy schedule to celebrate the Buddha’s Enlightenment with San Quentin’s Buddhadharma Sangha. Today’s social is our way of saying, thank you for your support.

My wife and I call our 10-year old son “V.” When he was younger, he would run by so fast we could barely get his initials out of our mouths before he was gone. Each Sunday, my wife and son come to visit me. Together, we talk about his school, Iraq, play station games, and more peaceful ways to live. Our weekly ritual is reading books together. One day after we finished, V. turned to me and said. “You are such a peaceful person. Why are you here?” What follows is our conversation.

My practice in life is ahimsa or nonviolence. It is by choice because of the harm I’ve caused so many over the years. In 1978 I was a Marine Corps Sergeant and military instructor stationed at Camp Pendleton. I was considered by many a “squared-away Marine.” Internally, my thoughts were filled with anger and materialism. I disliked everyone—including myself. These inner feelings were acted out one evening when I walked into a liquor store, robbed the store, moved the clerk, and shot him. My victim still suffers from the mental and physical trauma of that evening. I caused suffering not only to him, but to his family, my family, and the community, as well. I added to the suffering of the world through my very actions.

One would think that after such a violent act I would immediately start to work on the causes of my actions. Instead, I sat in a Folsom cell, dreaming of the past—fantasizing and recreating my life until it fit the way I wanted it to be. I would dream of the future: a nice house, expensive car, dog out front—materialism at its best. I missed the gift right in front of me, where transformation takes place. The only time I would come into contact with my inner feelings was after my family visited. When I returned to the housing unit, the coldness and depression were all around me. My fears of loneliness, the pain I really felt, arose. Yet within a few hours I returned to being a surface dweller.

In 1990, an individual called me to his bed area to show me something he had just received in the mail: a large tri-fold of a cosmic Buddha. As he showed it to me, he invited me to chant with him in the mornings and evenings. I thought: yeah, right! He gave me three items: a small tri-fold and two books. One of the books contained Dogen’s Fukanzazengi with commentary. After reading it, I decided to sit for the first time. Setting my alarm for 15 minutes, I crossed my legs. My hair stood straight up (I had hair back then!), I itched all over, my breath was erratic, and after what seemed like an eternity I stopped. This first sitting lasted two minutes, maybe even less. This was not for me. Yet during the day, I realized that my lack of patience and self-control were behavior patterns which carried into my relationships with others. So I made a decision to sit each day.

As I continued to sit, my ego showed up, I held a belief that meditation created a bubble around me and as the day wore on others pecked away at my self-imposed sanctuary. Only I can take a pure teaching and twist it to separate myself from others. To humble myself I began to practice the precepts, the paramitas, and deeply to examine the hindrances in my life. Slowly, my heart began to open.

Today my sitting begins each morning at 3:00 a.m. I sit and embrace my judgmental views, my fears, my anger, and my feelings of not being good enough. Somewhere between the tears and the breath of the moment there is stillness, a place where everything is just as it should be. As a neophyte to Buddhist practice. I’m learning to be present and responsible in each and every moment of life—while eating, washing, listening—and cultivating stillness when everything around me is chaotic. Only when intimately aware of my breath, living in the moment, does the thread which runs through all of us become so apparent. In the pain of others I see their search for peace and equanimity, as I discover my own. In this moment, with this breath, everything is the way it should be.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.