You’re becoming a what?

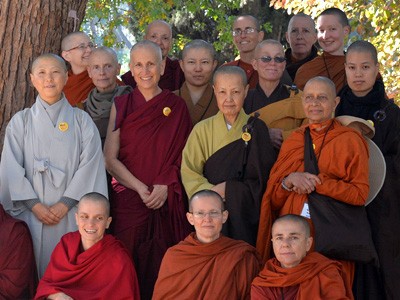

Living as a Western Buddhist nun

When people ask me to talk about my life, I usually start with “once upon a time….” Why? Because this life is like a dream bubble, a temporary thing—it is here and then gone, happening once upon a time.

I grew up in a suburb of Los Angeles, doing everything most middle-class American children do: going to school and on family vacations, playing with my friends and taking music lessons. My teenage years coincided with the Vietnam War and the protests against racial and sexual discrimination that were widespread in America at that time. These events had a profound effect on an inquisitive and thoughtful child, and I began to question: Why do people fight wars in order to live in peace? Why are people prejudiced against those who are different from them? Why do people die? Why are people in the richest country on earth unhappy when they have money and possessions? Why do people who love each other later get divorced? Why is there suffering? What is the meaning of life if all we do is die at the end? What can I do to help others?

Like every child who wants to learn, I started asking other people—teachers, parents, rabbis, ministers, priests. My family was Jewish, though not very religious. The community I grew up in was Christian, so I knew the best and worst of both religions. My Sunday school teachers were not able to explain in a way that satisfied me why God created living beings and what the purpose of our life was. My boyfriend was Catholic, so I asked the priests too. But I could not understand why a compassionate God would punish people, and why, if he were omnipotent, didn’t he do something to stop the suffering in the world? My Christian friends said not to question, just have faith and then I would be saved. However, that contradicted my scientific education in which investigation and understanding were emphasized as the way to wisdom.

Both Judaism and Christianity instruct “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” which certainly makes sense. But no one said how to, and I did not see much brotherly love in practice. Rather, Christian history is littered with the corpses of thousands of people who have been killed in the name of Christ. Some of my schoolteachers were open to discussing these issues, but they too had no answers. In the end, some people with kind intentions told me, “Don’t think so much. Go out with your friends and enjoy life.” Still, it seemed to me that there must be more to life than having fun, working, making money, having a family, growing old and dying. For lack of a sensible and comprehensive philosophy or religion to guide my life, I became a devout atheist.

After graduating from UCLA, I traveled, married, returned to school to do graduate work in Education and taught elementary school in the Los Angeles City Schools. During summer vacation in 1975, I saw a poster at a bookstore about a meditation course taught by two Tibetan Buddhist monks. Having nothing else to do and not expecting much, I went. I was quite surprised when the teachings by Ven. Lama Yeshe and Ven. Zopa Rinpoche proposed answers to the questions that had been with me since childhood. Reincarnation and karma explain how we got here. The fact that attachment, anger and ignorance are the source of all our problems explains why people do not get along and why we are dissatisfied. The importance of having a pure motivation shows that there is an alternative to hypocrisy. The fact that it is possible for us to abandon completely our faults and develop our good qualities limitlessly gives purpose to life and shows how each of us can become a person who is able to be of effective, wise, and compassionate service to others.

The more I investigated what the Buddha said, the more I found that it corresponded to my life experiences. We were taught practical techniques for dealing with anger and attachment, jealousy and pride, and when I tried them, they helped my daily life go better. Buddhism respects our intelligence and does not demand faith without investigation. We are encouraged to reflect and examine. Also, it emphasizes changing our attitudes and our heart, not simply having a religious appearance on the outside. All this appealed to me.

There was a nun leading the meditations at this course, and it impressed me that she was happy, friendly, and natural, not stiff and “holy” like many Christian nuns I had met as a child. But I thought that being a nun was strange—I liked my husband far too much to even consider it! I began to examine my life from the perspective of the Dharma, and the Buddha’s teachings resonated within me as I thought deeply about our human potential and the value of this life. There was no getting around the fact that death was certain, the time of death was uncertain, and that at death, our possessions, friends, relatives and body—everything that ordinary people spend their entire life living for—do not and cannot come with us. Knowing that the Dharma was something extremely important and not wanting to miss the opportunity to learn it, I quit my job and went to Nepal where Lama Yeshe and Zopa Rinpoche had a monastery and Dharma center.

Once there, I participated in the community life of work, teachings and meditation. The Dharma affected me more and more deeply as I used it to look at our present human situation and our potential. It was clear that my mind was overwhelmed by attachment, anger and ignorance. Everything I did was grossly or subtly under the influence of self-centeredness. Due to the karmic imprints collected on my mindstream through my unrestrained thoughts and actions, it was clear that a good rebirth was extremely unlikely. And if I really wanted to help others, it was impossible to do if most of my attitudes were self-centered, ignorant and unskillful.

I wanted to change, and the question was how? Although many people can live a lay life and practice the Dharma, I saw that for me it would be impossible. My disturbing attitudes—ignorance, anger and clinging attachment—were too strong and my lack of self-discipline too great. I needed to make some clear, firm ethical decisions about what I would and would not do, and I needed a disciplined lifestyle that would support, not distract me from, spiritual practice. The monastic lifestyle, with the ethical discipline its precepts provide, was a viable option to fulfill those needs.

My family did not understand why I wanted to take ordination. They knew little about Buddhism and were not spiritually inclined. They did not comprehend how I could leave a promising career, marriage, friends, family, financial security and so forth in order to be a nun. I listened and considered all of their objections. But when I reflected upon them in light of the Dharma, my decision to become a nun only became firmer. It became more and more clear to me that happiness does not come from having material possessions, good reputation, loved ones, physical beauty. Having these while young does not guarantee a happy old age, a peaceful death, and certainly not a good rebirth. If my mind remained continually attached to external things and relationships, how could I develop my potential and help others? It saddened me that my family did not understand, but my decision remained firm, and I believed that in the long-run I would be able to benefit others more through holding monastic vows. Ordination does not mean rejecting one’s family. Rather, I wanted to enlarge my family and develop impartial love and compassion for all beings. With the passage of time, my parents have come to accept my being Buddhist and being a nun. I did not try to convince them through discussion or with reasoning, but simply tried as best as I could to live the Buddha’s teachings, especially those on patience. Through that they saw that not only am I happy, but also that what I do is beneficial to others.

My husband had ambivalent feelings. He was a Buddhist, and the wisdom side of him supported my decision, while the attachment side bemoaned it. He used the Dharma to help him through this difficult time. He has subsequently remarried and is still active in the Buddhist community. We get along well and see each other from time to time. He is supportive of my being a nun, and I appreciate this very much.

Taking ordination

Having vows is not restricting. Rather, it is liberating, for we free ourselves from acting in ways that, deep in our hearts, we do not want to.

In the spring of l977, with much gratitude and respect for the Triple Gem and my spiritual teachers, I took ordination from Kyabje Ling Rinpoche, the senior tutor of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. People ask if I have ever regretted this. Not at all. I earnestly pray to the Triple Gem to keep my ordination purely and be able to be ordained in future lives as well. Having vows is not restricting. Rather, it is liberating, for we free ourselves from acting in ways that, deep in our hearts, we do not want to. We take the vows freely, nothing is forced or imposed. The discipline is voluntarily undertaken. Because we endeavor to live simply—without many possessions, entangled emotional relationships or preoccupation with our looks—we have more time for the inner exploration Dharma practice requires and for service oriented activities. If I had a career, husband, children, many hobbies, an extensive social life and social obligations, it would be difficult for me to travel to teach or to receive teachings as much as I do now. The vows also clarify our relationships; for example, my relationships with men are much more straightforward and honest now. And I am much more comfortable with my body. It is a vehicle for Dharma practice and service and so must be respected and kept healthy. But wearing robes and shaving my head, I am not concerned with my appearances. If people like me, it will have to be because of inner beauty, not external beauty. These benefits of simplicity become evident in our lives as we live according to the precepts.

Our vows center around four root precepts: to avoid killing, stealing, sexual relations, and lying about our spiritual attainments. Other precepts deal with a variety of aspects of our life: our relationships with other monastics and lay people, what and when we eat and drink, our clothes and possessions. Some precepts protect us from distractions that destroy our mindful awareness. My personal experience has been that much internal growth has come from trying to live according to the precepts. They make us much more aware of our actions and their effects on those around us. To keep the precepts is no easy job—it requires mindfulness and continuous application of the antidotes to the disturbing attitudes. In short, it necessitates the transformation of old, unproductive emotional, verbal and physical habits. Precepts force us to stop living “on automatic,” and encourage us to use our time wisely and to make our lives meaningful. Our work as monastics is to purify our minds and develop our good qualities in order to make a positive contribution to the welfare of all living beings in this and all future lives. There is much joy in ordained life, and it comes from looking honestly at our own condition as well as at our potential.

Ordained life is not clear sailing, however. Our disturbing attitudes follow us wherever we go. They do not disappear simply because we take vows, shave our head and wear robes. Monastic life is a commitment to working with our garbage as well as our beauty. It puts us right up against the contradictory parts of ourselves. For example, one part of us feels there is a deep meaning to life, great human potential and has a sincere wish to actualize these. The other part of us seeks amusement, financial security, reputation, approval and sexual pleasure. We want to have one foot in nirvana (liberation), the other in samsara (the cycle of constantly recurring problems). We want to change and go deeper in our spiritual practice, but we do not want to give up the things we are attached to. To remain a monastic, we have to deal with these various sides of ourselves. We have to clarify our priorities in life. We have to commit to going deeper and peeling away the many layers of hypocrisy, clinging and fear inside ourselves. We are challenged to jump into empty space and to live our faith and aspiration. Although life as a monastic is not always smooth—not because the Dharma is difficult, but because the disturbing attitudes are sneaky and tenacious—with effort, there is progress and happiness.

While Catholic nuns enter a particular Order—for example, a teaching order, a contemplative order, a service order—Buddhist nuns have no prescribed living situation or work. As long as we keep the precepts, we can live in a variety of ways. During the nearly nineteen years I have been ordained, I have lived alone and in community. Sometimes I studied, other times taught; sometimes worked, other times done intensive, silent retreat; sometimes lived in the city, other times in the countryside; sometimes in Asia, other times in the West.

Buddhist teachers often talk about the importance of lineage. There is a certain energy or inspiration that is passed down from mentor to aspirant. Although previously I was not one to believe in this, during the years of my ordination, it has become evident through experience. When my energy wanes, I remember the lineage of strong, resourceful women and men who have learned, practiced and actualized the Buddha’s teachings for 2,500 years. At the time of ordination, I entered into their lineage and their life examples renew my inspiration. No longer afloat in the sea of spiritual ambiguity or discouragement, I feel rooted in a practice that works and in a goal that is attainable (even though one has to give up all grasping to attain it!)

As one of the first generation of Western nuns in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, there are certain challenges that I face. For example, because our Tibetan teachers are refugees from their own country, they cannot support their Western ordained disciples. Their primary concern is to rebuild their monasteries in exile and take care of the Tibetan refugee community. Therefore, Western monastics have no ready-made monasteries or support system. We are expected to provide for ourselves financially, although it is extremely difficult to maintain our vows if we have to put on civilian clothes and work in the city. If we stay in India to study and practice, there are the challenges of illness, visa problems, political unrest and so forth. If we live in the West, people often look at us askance. Some times we hear a child say, “Look, Mommy, that lady has no hair!” or a sympathetic stranger approaches us and says, “Don’t worry, you look lovely now. And when the chemo is over, your hair will grow back.” In our materialistic society people query, “What do you monastics produce? How does sitting in meditation contribute to society?” The challenges of being a Buddhist nun in the West are many and varied, and all of them give us a chance to deepen our practice.

Being a Western nun in the Tibetan tradition

A great part of Buddhist practice is concerned with overcoming our grasping at an identity, both our innate feeling of self and that which is artificially created by the labels and categories that pertain to us this lifetime. Yet I am writing about being a Western nun in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, a phrase that contains many categories. On a deeper level, there is nothing to grasp to about being Western, a nun, a Buddhist, or from the Tibetan tradition. In fact, the essence of the monastic lifestyle is to let go of clinging to such labels and identities. Yet on the conventional level, all of these categories and the experiences I have had due to them have conditioned me. I wish to share with you how these have influenced me and in doing so, will write more about my projections and disturbing attitudes than comment on the external circumstances I encountered. As limited sentient beings, our minds are often narrow, critical and attached to our own opinions, and this makes situations in our environment appear difficult. This is not to say that external circumstances and institutions never need to be challenged or changed, but that I am emphasizing the internal process of using difficult situations as a chance for practice.

Being a Westerner means I have been conditioned to believe that democracy and equality—whatever those two terms mean—are the best way for human beings to live together. Yet I have chosen to become a monastic and thus in others’ eyes become associated with an institution that is seen in the West as being hierarchical. There are two challenges here: one is how I relate to the hierarchy, the other is how I am affected by Westerners who see me as part of a hierarchical institution.

In many ways the hierarchy of the monastic institution has benefited me. Being a high achiever, I have tended to be proud, to want to add my opinion to every discussion, to want to control or fix situations that I do not like or approve of. Dharma practice itself has made me look at this tendency and to reflect before acting and speaking. In particular it has made me aware of when it is suitable to speak and when it is not. For example, as part of receiving the bhikshuni ordination in Taiwan, I participated in a thirty-two day training program, in which I was one of two foreigners in the five hundred people being ordained. Each day we spent about fifteen minutes filing from the main hall into the teaching hall. A quicker, more efficient method of moving so many people from place to place was clear to me, and I wanted to correct the waste of time and energy I saw. Yet it was also clear that I was in the role of a learner and the teachers were following a system that was tried and true. Even if I could have made my suggestion known in Chinese, no one would have been particularly interested in it. I had no alternative but to keep quiet, to do it their way and to be happy doing so. In terms of practice, this was a wonderful experience for me; one which I now treasure for the humility, open-mindedness, and acceptance it taught me.

Hierarchy in Buddhism manifests differently in the West. Sometimes race, ethnicity and culture are the discriminating factors. Some Westerners feel that if they adopt Asian cultural forms, they are practicing the Dharma. Some assume that Asians—being from far away and therefore exotic—are holy. Meanwhile, other Westerner practitioners grew up with Mickey Mouse like everyone else, and seem ordinary. I am not saying that Western practitioners are equal in realizations to our Asian teachers. There is no basis for such generalizations, because spiritual qualities are completely individual. However, fascination with the foreign—and therefore exotic—often obscures us from understanding what the path is. Spiritual practice means that we endeavor to transform ourselves into kind and wise people. It is not about idolizing an exotic teacher or adopting other cultural forms, but about transforming our minds. We can practice the Dharma no matter what culture we or our teacher come from; the real spiritual path cannot be seen with the eyes for it lies in the heart.

As a Westerner, I have a unique relationship with the Tibetan Buddhist religious institution. On one hand, I am a part of it because I have learned so much from the Tibetan teachers in it and have high regard for these spiritual masters and the teachings they have preserved. In addition, I am part of the monastic institution by virtue of having taken ordination and living a monastic lifestyle. On the other hand, I am not part of the Tibetan religious institution because I am a Westerner. My knowledge of Tibetan language is limited, my values at times differ from the Tibetans, my upbringing is different. Early on in my practice, when I lived primarily in the Tibetan community, I felt handicapped because I did not fit into their religious institutions. However, over the years the distinction between spiritual practice and religious institutions has become clearer to me. My commitment is to the spiritual path, not to a religious institution. Of course it would be a wonderful support to my practice to be part of a religious institution that functioned with integrity and to which I felt I really belonged, but that is not my present circumstance. I am not a full member of the Tibetan religious institutions and Western ones have either not yet been established or are too young.

Making the distinction between spiritual path and religious institution has made me see the importance of constantly checking my own motivation and loyalty. In our lives, it is essential to discriminate Dharma practice from worldly practice. It is all too easy to transplant our attachment for material possessions, reputation and praise into a Dharma situation. We become attached to our expensive and beautiful Buddha images and Dharma books; we seek reputation as a great practitioner or as the close disciple of one; we long for the praise and acceptance of our spiritual teachers and communities. We think that because we are surrounded by spiritual people, places and things, that we are also spiritual. Again, we must return to the reality that practice occurs in our hearts and minds. When we die, only our karma, our mental habits and qualities come with us.

Being a woman in the monastic institution has been interesting as well. My family believed in the equality of men and women, and since I did well in school, it was expected that I would have a successful career. The Tibetans’ attitude towards nuns is substantially different from the attitudes in my upbringing. Because the initial years of my ordination were spent in the Tibetan community, I tried to conform with their expectations for nuns. I wanted to be a good student, so during large religious gatherings I sat in the back of the assembly. I tried to speak in a low voice and did not voice my views or knowledge very much. I tried to follow well but did not initiate things. After a few years, it became obvious that this model for behavior did not fit me. My background and upbringing were completely different. Not only did I have a university education and a career, but I had been taught to be vocal, to participate, to take the initiative. The Tibetan nuns have many good qualities, but I had to acknowledge the fact that my way of thinking and behaving, although greatly modified by living in Asia, was basically Western.

In addition, I had to come to terms with the discrimination between men and women in the Tibetan religious institution. At first, the monks’ advantages made me angry: in the Tibetan community, they had better education, received more financial support and were more respected than the nuns. Although among Western monastics this was not the case, when I lived in the Tibetan community, this inequality affected me. One day during a large offering ceremony at the main temple in Dharmsala, the monks as usual stood up to make the personal offering to His Holiness. I became angry that the monks had this honor, while the nuns had to sit quietly and meditate. In addition, the monks, not the nuns, passed out the offerings to the greater assembly. Then a thought shot through my mind: if the nuns were to stand up to make the offering to His Holiness and pass out the offerings while the monks meditated, I would be angry because the women always had to do the work and the men did not. At that point, my anger at others’ prejudice and gender discrimination completely evaporated.

Having my abilities as a woman challenged by whatever real or perceived prejudice I encountered in the Asian monastic system, and Asian society in general (not to mention the prejudice in Western societies) has been good for my practice. I have had to look deeply within myself, learn to evaluate myself realistically, let go of attachment to others’ opinions and approval and my defensive reactions to them, and establish a valid basis for self-confidence. I still encounter prejudice against women in the East and in the West, and while I try to do what is practical and possible to alleviate it, my anger and intolerance are largely absent now.

Being a Buddhist monastic in the West

Being a monastic in the West has its interesting points as well. Some Westerners, especially those who grew up in Protestant countries or who are disillusioned with the Catholic Church, do not like monasticism. They view it as hierarchical, sexist, and repressive. Some people think monastics are lazy and only consume society’s resources instead of helping to produce them. Others think that because someone chooses to be celibate that they are escaping from the emotional challenges of intimate relationships and are sexually repressed. These views are common even among some non-monastic Dharma teachers and long-time practitioners in the West. At times this has been difficult for me, because, having spent many years living as a Westerner in Asian societies, I expected to feel accepted and at home in Western Dharma circles. Instead, I was marginalized by virtue of being part of the “sexist and hierarchical” monastic institution. Curiously, while women’s issues are at the forefront of discussion in Western Buddhism, once one becomes a monastic, she is seen as conservative and tied to a hierarchical Asian institution, qualities disdained by many Westerners who practice Buddhism.

Again, this has been an excellent opportunity for practice. I have had to reexamine my reasons for being a monastic. The reasons remain valid and the monastic lifestyle is definitely good for me. It has become clear that my discomfort is due to being attached to others’ approval, and practice means subduing this attachment.

Nevertheless, I am concerned that a variety of lifestyle options is not being presented to Western Buddhists. While many people believe the monastic model is stressed too much in Asia, we must be careful not to swing the pendulum to the other extreme and only present the house-holder model in the West. Because people have different dispositions and tendencies, all lifestyles must be accepted in the panorama of practitioners. There is no need to make one better and another worse, but to recognize that each of us must find what is suitable for ourselves and recognize that others may chose differently. I especially appreciated the perspective of a non-monastic Western Dharma teacher who said, “At one time or another, most of us have thought of becoming monastics—of creating a lifestyle where we have less commitments to work and family and more time to spend on practice. For whatever reason we decided not to take that route now, but I treasure that part of myself that is attracted to that lifestyle. And I am glad that other people live that.”

In contrast to those who depreciate us for being monastics, some people, both Western and Asian, have very different projections on monastics. Sometimes they think we must be nearly enlightened; other times they liken us to the strict authority figures they encountered in religious institutions as children. Being simply a human being, I find it challenging to deal with both of these projections. It is isolating when people expect us to be something we are not because of our role. All Buddhists are not yet Buddhas, and monastics too have emotional ups and downs and need friends. Similarly, most of us do not wish to be regarded as authority figures; we prefer discussion and the airing of doubts.

I believe other Western practitioners share some of the challenges that I face. One is establishing a safe ambiance in which we can talk openly about their doubts and personal difficulties in the practice. In general this is not needed for Asian practitioners because they grew up in a Buddhist environment and thus lack many of the doubts Westerners have because we have changed religions. Also, Westerners relate to their emotions differently and our culture emphasizes growth and development as an individual in a way that Asian cultures do not. This can be both an advantage and a disadvantage in spiritual practice. Being aware of our emotions enables us know our mental processes. Yet we are often aware of our emotions in an unproductive way that increases our self-centeredness and becomes a hindrance on the path. There is the danger that we become pre-occupied with our feelings and forget to apply the antidotes taught in the teachings to transform them. Instead of meditating on the Dharma, we meditate on our problems and feelings; we psychologize on the meditation cushion. Instead we must contemplate the Buddha’s teachings and apply them to our lives so they have a transformative effect.

Similarly, the Western emphasis on individuality can be both an asset and a hindrance to practice. On one hand, we want to grow as a person, we want to tap into and develop our potential to become a Buddha. We are willing to commit ourselves to a spiritual path that is not widely known or appreciated by our friends, family and colleagues. On the other hand, our individuality can make it difficult for us to form spiritual communities in which we need to adapt to the needs and wishes of others. We easily fall into comparing ourselves with other practitioners or competing with them. We tend to think of what we can get out of spiritual practice, or what a spiritual teacher or community can do for us, whereas practice is much more about giving than getting, more about cherishing others than ourselves. His Holiness the Dalai Lama talks about two senses of self: one is unhealthy—the sense of a solid self to which we grasp and become pre-occupied. The other is necessary along the path—the valid sense of self-confidence that is based on recognizing our potential to be enlightened. We need rethink the meaning of being an individual, freeing ourselves from the unhealthy sense of self and developing valid self-confidence that enables us to genuinely care for others.

As Buddhism comes to the West, it is important that the monastic lifestyle is preserved as a way of practice that benefits some people directly and the entire society indirectly. For those individuals who find strict ethical discipline and simplicity helpful for practice, monasticism is wonderful. The presence of individual monastics and monastic communities in the West also affects the society. They act as an example of people living their spiritual practice together, working through the ups and downs in their own minds as well as the continuous changes that naturally occur when people live together. Some people have remarked to me that although they do not wish or are not yet prepared to become a monastic, the thought that others have taken this road inspires them and strengthens their practice. Sometimes just seeing a monastic can make us slow down from our busyness and reflect for a moment, “What is important in my life? What is the purpose of spiritual paths and religions?” These questions are important to ask ourselves, they are the essence of being a human being with the potential to become a Buddha.

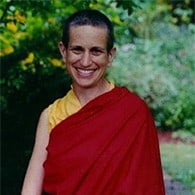

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.