Refuting the Cittamatra view

03 Commentary on the Awakening Mind

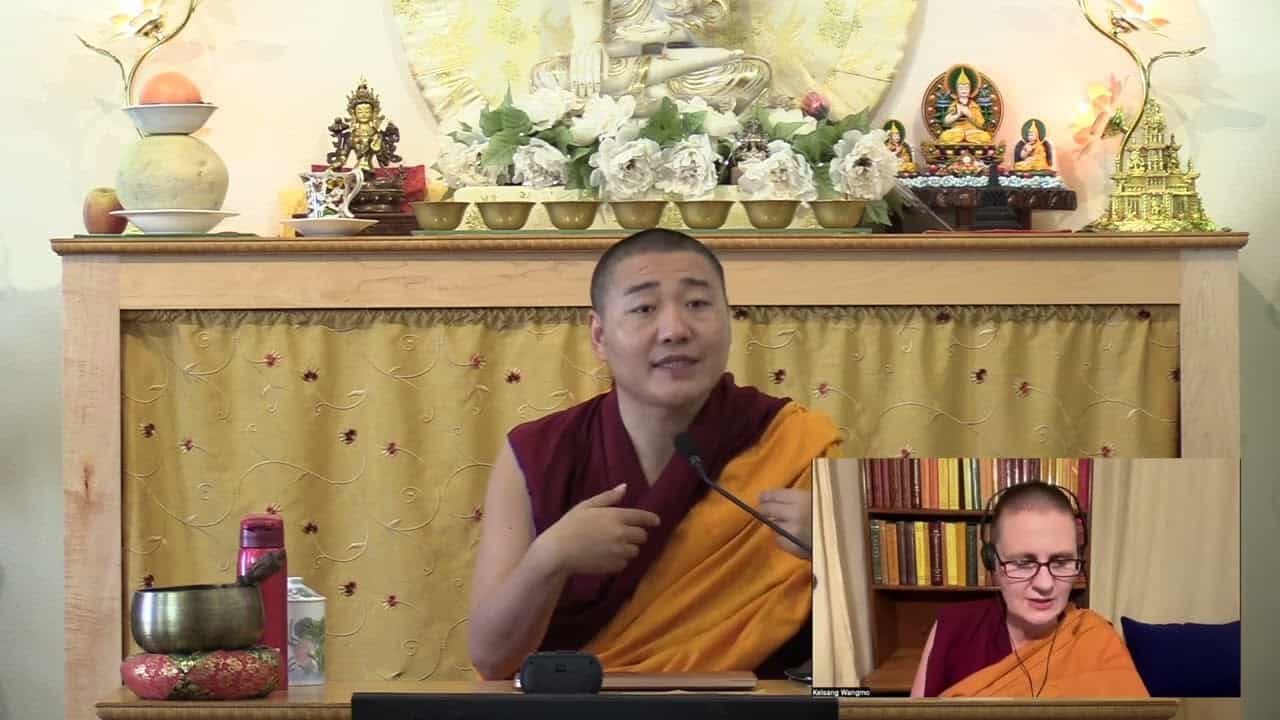

Translated by Geshe Kelsang Wangmo, Yangten Rinpoche explains A Commentary on the Awakening Mind.

Clearing up confusion

I want to say a few things about verse 16 before getting into verse 26. So, verse 16 says:

Neither atom of form exists nor is sense organ elsewhere;

Even more no sense organ as agent exists;

So the producer and the produced

Are utterly unsuited for production.

I talked about this last time, but it was not very clear. This text has been translated from Sanskrit into Tibetan, therefore it’s different from the texts that have been composed in Tibetan right from the beginning. It has also to do with the translator, so sometimes the translation may be a little difficult. It’s difficult to understand this verse in particular. We can kind of explain it, but it’s a little difficult. What is really the intent of the author? It’s important to understand what the author means. So, when we read this verse, we can look at the other verses above and below and put it into context. Then it becomes clear that the meaning, as I said before, is that neither atom of form exists. There’s no partless atom when we have the aggregation of phenomena. When things come together, it’s an aggregation of many particles, and there’s no partless particle. But he’s saying there’s no sense organ.

In the commentary on the 400 verses, for instance, it says that there’s no aggregation. It’s basically saying that these partless particles are not the object of the sense consciousness. This quote is also given in the Lamrim Chenmo as part of the special insight section. The sense organs are also an aggregation of many atoms, but it’s not possible that you have an aggregation of partless particles or partless atoms that then serve as a sense organ. That doesn’t work. So then when we speak of the external atoms or external particles, that is impossible. There are no external partless particles. But also, in terms of the internal form, such as the sense organ or the sense power, it’s also not possible that the particles that form this particular sense power are partless. Sometimes this word power here is also used to mean a creator god.

Anyway, here it’s not possible to have this kind of sense power. These verses refute the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika. When it comes to the physical world, everything that forms, what is the building block of the external world? They say it’s this partless atom. Then with regard to the self or with regard to the person, what do they say is the fundamental building block of a person? They say it is a partless moment in time: a shortest moment in time that can no longer be divided. The mind’s shortest moment in time that can no longer be further divided, that is the fundamental building block of mind. So, there you have the external and the internal fundamental building blocks according to these two Buddhist schools. That’s what the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika asserts.

But that is not accepted by the other schools, as it explains when it says, “Neither atom of form exists nor is sense organ elsewhere.” With regard to atoms in particular, whether we talk about the external atoms or the internal atoms, it’s impossible that these partless atoms form the external material world or the internal sense organs. In this context also, what is implied is that there is no creator god, just as before we talked about no permanent self. There’s no permanent self; therefore, there’s no permanent creator either. The non-Buddhist systems accept, for instance, a permanent self. But that is impossible because of cause-and-effect: a cause has to be impermanent to give rise to an effect and so forth. As I explained before, this is not correct. If there were a permanent self, then cause and effect wouldn’t make sense. And this has been refuted before.

Now, following this, what is refuted is the view of the two lower Buddhist philosophical schools. And from there, we move on to the Cittamatra school. These views of all these different schools are refuted, and they’re built on top of each other. First you have the refutation of the non-Buddhist system and then you continue on. With verse 16, it wasn’t really that clear. It’s a little difficult to explain. Anyway, seeing the different commentaries, I kind of remembered that there’s not much explanation. It’s very difficult to find an explanation of verse 16, for instance, and there was very little time to get prepared. There is a commentary on this particular text, but it’s very short. It’s not that extensive. It doesn’t explain, for instance, this verse, which is difficult. And it still seems that in this text that there are some verses missing. I still have that sense. It seems a little odd. There may have been a mistake.

Refuting partless atoms

So anyway, it was clear to me this morning that I didn’t explain verse 16 very clearly. Then after class someone asked me a question, so I would like to share this question with you because I think it’s beneficial. They asked why the author of this text refutes partless atoms. It’s not necessary. To be more exact, what is the relationship between saying that there’s no partless atoms and saying that three different beings have different appearances? That has to do with the inference. How does that connect? What’s the connection between the different appearances that sentient beings have and the refutation of partless particles? There doesn’t seem to be a connection.

There is a connection when we discuss the refutation—when we refute these two philosophical schools. People say, for instance, “This is good; this is bad. This is gas, and this is blood. This is water,” and etc. The Sautrantika and Vaibhasika would say all these phenomena that appear to us are the result of partless particles. They believe that it all comes down to these smallest particles, these partless particles. And the external world is an aggregation of all these partless particles. This is how our external world forms according to the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika says. Whether it’s an apple or a peach or all these different objects—houses, etc.—they come together. They’re like an aggregation of these very subtle particles.

And then with regard to consciousnesses, they don’t accept that there are imprints ripening on the basis of that. We see an apple; we see a peach. They don’t accept that at all. They say everything exists from the side of the object in terms of there being these partless particles that then form the external world. It’s got nothing to do with the mind. There’s this objective world out there because of these partless particles. Therefore, there’s a connection. Apples and so forth are this aggregation of these subtle particles. They say that’s got nothing to do with our mind. It’s just that we see what’s there. Therefore, it seems there’s no relation to the different imprints in the mind, for instance. But actually, when we talk about these partless particles, I understand where this question comes from. Even in my case, I sometimes feel that “Oh, it’s not very clear why.” But in summary, what are these external objects made of? What are their building blocks? The building blocks are these partless particles, partless atoms. That’s their view. In their view, there’s this kind of final, ultimate building block. Then that building block forms everything.

But actually, everything that they built must have parts. So, all the parts must have parts. Their view is basically that if there were particles like these fundamental building blocks, if they had parts, they would say that you could divide it endlessly. You can divide these particles endlessly. And there will never be a time when they form aggregates, that they form coarser objects. That’s their assertion: that it’s impossible. Therefore, if you can divide up each particle further in smaller parts, then it’s endless and you never reach a point where many particles come together to form something coarser. That being the case, they assert a particle that is like a fundamental building block that exists fundamentally as a partless entity, a final kind of entity. And for that reason, they also don’t speak about imprints. They say there’s no subjective kind of perception with regard to imprints ripening and so forth. Instead, there’s this objective world, and it’s very fundamentally true, etc.

Having this true existence out there then imprints don’t play any part. Therefore, when we talk about different phenomena that appear to us, they don’t talk of them as mere appearances or as imprints ripening. There’s this sense of just an objective world: because of these partless particles, everything comes into existence. Actually, in the Madhyamaka school, they don’t say that everything is in the nature of mind, but they say that everything appears to us because of imprints. This part they accept here in this way; Cittamatra and Madhyamaka are similar. They do say that, for instance, the reason we see pus or blood or water or nectar or so forth has to do with the imprints in our mind. For instance, as a result of accumulating virtuous karma, when we are in a room such as this, we have a special feeling. We have a special perception of this room. Whether we perceive this as beneficial or not, it all has to do with our karma. The experience of just being in this building is different if we’ve accumulated a lot of positive karma. So, our experiences are connected to the different karmic imprints ripening.

The Cittamatra view

Anyway, let’s continue with the text. We are on verse 26. What is this verse about? It presents the view of the Cittamatra school.

For those who propound consciousness [only]

This manifold world is established as mind [only]

What might be the nature of that consciousness?

I shall now explain this very point.

Now, what does the mind-only school say with regard to the mind? They say the mind exists substantially. The mind exists truly. They say that, for instance, the mind basis of all that is the self. And that I will explain. These three lines explain the Cittamatra school. They say that all phenomena is in the nature of the mind. There is no external object. Everything is just an appearance to the mind. When we say the forms of physical objects appear to the mind, they’re mere appearances. They don’t exist externally to the mind. It seems like the external objects are very distant from the mind: they’re over there. The mind is over here, and the objects are over there. There’s a sense of distance. There’s a sense of disconnect between the mind and its object—this mind that perceives objects to be disconnected, to be over there, to be distant. So, whether it’s visual forms or sounds and so forth, there’s this sense of a very clear difference between mind and object. This appearance is mistaken.

When it comes to the external appearances, they don’t exist in the way as external objects. They are just appearances to the mind. It’s like when you dream of a horse: at that time, there is no actual horse out there. It’s just an appearance to the mind. And the mind itself, according to the Chittamatra school, exists truly. If everything is just a mistaken appearance, and then the mind is also mistaken, that doesn’t work. According to this school, something has to be truly existent in order to account for the fact that the external appearances are mistaken, or that there’s a mistaken aspect to them. All these different objects—beautiful things, ugly things, pleasing and unpleasing objects—none of them exist the way they appear. But then the mind has to have a more real existence. So, phenomena are mere appearances to the mind, which is why the mind has to be truly existent, has to exist in a slightly different way. That’s how the Cittamatra school explains it. It’s not possible to say that everything is false. According to the Chittamatra school, they wouldn’t be able to explain it that way—that everything is false.

Later, some of the verses also talk about the three natures. And based on that, the Cittamatra school is refuted. But here, we get a rough sense of what the Cittamatra school is all about. If all phenomena are merely in the nature of the mind—if external phenomena don’t exist—in that case, there are actually a lot of reasonings for the Cittamatra school. The Cittamatra school applies a lot of reasons for saying so. And also there are scriptural quotes that say all phenomena come from the mind. There’s only mind; all the environment is merely mind. Therefore, the Buddha has actually talked about that. The Buddha himself taught the Cittamatra school. Now we need to recognize the contradiction to other explanations the Buddha has given as a way of understanding that these teachings cannot be taken literally. When we say all phenomena are merely mind, we’re not saying that nothing exists. That would be extreme. The objects we see around us, the physical objects, are like reflections. For instance, it’s like the reflection in a mirror and a mirage. There is an existence there, of course. We’re not saying everything is non-existent. We’re not saying everything is mistaken. We’re not saying there’s nothing there.

If we say that nothing exists the way it appears then that would be difficult, but there is a purpose for this. The Buddha said all of this is but one’s mind in order to alleviate the fear of childish beings. So here the mind really becomes like a creator god. It says, for instance, in Entry into the Middle Way that it’s the mind that is responsible for the external and the internal environment. We don’t say the mind is really like a creator god in the same sense as God is asserted to be a creator of the environment, but there’s some similarity that everything arises from the mind. Everything arises through the mind because of appearing to the mind. For instance, when we talk about samsara, it is the mind that creates samsara. The mind is responsible for liberation. So, the difference between samsara and liberation all comes down to the mind. The difference exists on the basis of the mind.

Refuting the Cittamatra view

Ordinary beings, childish beings, have fear. They’re fearful. And to overcome particular types of fear, the Buddha taught the Cittamatra school. He taught that the external objects are mere appearances, but that the mind really exists. That is the creator of reality. This is actually accepted to be interpretative. It needs to be interpreted; it’s not definitive. Then the text continues with refuting the Cittamatra view with verse 28:

The imputed, the dependent,

And the consummate—they have

Only one nature of their own, emptiness;

Their identities are constructed upon the mind.

Imputed refers to the imputed phenomena that exist and imputed phenomena that don’t exist. This refers to, for instance, uncompounded space. A lot of permanent phenomena are included in the imputed nature. The basis of perception of a mind and so forth—these are considered to be permanent. They’re considered to be imputed. And then dependent refers to all the permanent phenomena. And the consummate here is thoroughly established. So we say, for instance, that the dependent—the emptiness of the imputed on the basis of the dependent—is the consummate. So for instance, when Lu appears to a conceptual mind, from the point of view of Lu being the basis of the conceptual mind, it doesn’t exist by way of its own characteristics. So, this is the consummate.

And we talk about external phenomena, for instance, like form and so forth. They appear to be external phenomena. When they appear to the mind, as a result of the imputed nature, they appear as separate from the mind. They appear as different substantial entities. But the lack of mind and its object existing as different substantial entities is also described as emptiness. So here, for instance, the object of negation of emptiness is imputed. And the emptiness of that is the consummate. Their identities are constructed upon the mind.

In the Cittamatra school, you have these three natures. But based on that, the Madhyamaka system is different. They don’t really talk about the three natures. So, there’s only one nature of their own emptiness: their identities are constructed upon the mind. When we talk about how the mind exists or the way the mind appears or its nature, being a conventional truth, everything has to do with the mind here. So, the appearances are described as imputed. Then the mind itself is a dependent phenomenon. And then the emptiness of the mind, that’s the consummate.

So, these three characteristics, these three natures of the mind, although they’re explained in the Cittamatra school, the Madhyamaka school can explain them as well. There’s no contradiction to the Madhyamaka view, even though they may not explain them to the same degree. When we say, for instance, the mind being clear knowing, when the mind perceives an object, it perceives different objects. It perceives true existence. It perceives that mind and object are different substantial entities. It perceives impermanent, prominent phenomena. It has all these different appearances that arise in the mind. Things appear differently, so different imputed phenomena appear to the mind.

And then the mind itself is a dependent phenomenon. Many of the appearances are imputed phenomena. However, many of the objects that appear to the mind that don’t exist are imputed and they’re emptiness. In the case of, for instance, external existence, that is the consummate. So, all this is explained in relation to the mind. There’s only one nature of their own emptiness. Their identities are constructed upon the mind.

Does mind exist truly?

Then verse 29 says:

To those who delight in the great vehicle

The Buddha taught in brief

Selflessness in perfect equanimity;

And that the mind is primordially unborn.

What does it say in the commentaries? I’m not sure. There may be some connection to the tantric path, but I’m not sure this is the case. Anyway, here when we say the universal vehicle with regard to the Madhyamaka, the great vehicle actually refers to the Madhyamaka views, in the sense that phenomena don’t exist externally. They don’t exist truly, but the mind exists truly. For instance, with the five aggregates, in the other schools they say everything exists the way it appears, but the Cittamatra school says that there are no external phenomena. Only the mind itself exists truly. So, there’s this difference.

In the lower two schools, Vibhasika and Tantric, they say phenomena’s external existence exists truly. That’s not what the Cittamatra accepts. They don’t say they’re external phenomena, but they say the mind exists truly. But actually, all phenomena have to have the same existence. In the Madhyamaka school, they say that all phenomena equally lack true existence. So therefore, the mind is primordially unborn. Even the mind doesn’t exist truly. In the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, this is explained very extensively.

When it says “Devoid of entities” and so forth, the quote from the Guhyasamaja Tantra explained that. It also says that the mind and objects have an equal existence when it comes to true existence. This root tantra also mentions that. This is actually taught for those of greater intelligence.

Then verse 30 says:

The proponents of yogic practices assert

That a purified mind [effected] through

Mastery of one’s own mind

And through utter revolution of its state

Is the sphere of its own reflexive awareness.

Our mind right now is defiled. We have so many different defilements. For instance, we have the coarser ones when we talk about intellectually acquired affections. In the Svatantrika school, they don’t talk about cognitive obstructions that are intellectually acquired. They don’t distinguish in that way. In the Svatantrika school, they distinguish between intellectually acquired and innate cognitive obstructions. I don’t think the Prasangika school would have said that.

They don’t say that imprints are intellectually acquired and so forth. They don’t apply that terminology. With the mind that realizes emptiness directly, there’s a self-knower, a reflexive awareness. Therefore, in the Cittamatra school, they have to assert this kind of reflexive awareness or this self-knower because otherwise they can’t account for the fact that the consciousness exists truly. So, when we say something exists, we can only say it exists because we saw it—because there’s a mind that sees it. For instance, if you ask, “Is there food inside your room?” you answer yes, because you saw it or you ate it. There must be a consciousness. There must be a mind. For instance, with regard to an object, if we ask does it exist or not then we can only determine its existence if there’s a mind that perceives that. So, what about the mind itself?

In the Cittamatra school, they say the mind exists truly. So, what is it that determines that the mind exists truly? Well, that’s the self-knower. Because otherwise, if that didn’t exist, then another person would have to decide whether our mind exists or not. But then their mind also has to be perceived by another person’s mind. And now you have this endless regress. This is something that neither the Cittamatra nor the Madhyamakas would assert. So, you must have another mind that perceives sense consciousness, for instance, and that then determines that the sense consciousness exists truly. Therefore, they assert a self-knower, a reflexive awareness. This particular mind is asserted in the Chittamatra school.

Is it possible for phenomena to arise from something inherently different? Some people would say, “Well yeah, you can see it. You can see that phenomena arise from something inherently different.” Likewise, the Cittamatra school argues, “Of course, the mind exists truly. You have a mind that perceives it as existing truly.” So, how do we determine whether something exists or not? Well, it must have a mind that perceives it. This is similar here.

And then with regard to the self-knower, the self-knower knows itself. So, we don’t need another mind. That’s the assertion when it comes to the self-knower, the reflexive awareness. For instance, a fire that is hot heats up itself. You don’t need another entity, another source, that heats the fire. The fire itself heats itself. If you have a butter lamp, for instance, the clarity or the illumination of the butter lamp comes from itself. It doesn’t need an external source of light. The clarity or the light of the butter lamp exists truly. And also a fire establishes itself—the heat comes from itself or the light comes from itself. That’s how the Chittamatra school argues.

They say that, for instance, the self-knower knows itself or the mind exists by itself. Its whole nature comes from itself. It doesn’t need anything else to exist. It’s just in the same way as the light comes from the butter lamp. All the light comes from the butter lamp itself. It doesn’t need an external light source. Therefore, it illuminates itself, basically. So, you can see the butter lamp because the light comes from itself that illuminates itself. It’s something that comes from the side of the object. It has everything it needs. The butter lamp has everything it needs to illuminate itself. It doesn’t depend on anything else to be able to do so. That’s how the Cittamatra explains it, but the Madhyamaka doesn’t assert this.

Dependence on other factors

In the Madhyamaka school, they say that there are other phenomena responsible for the butter lamp illuminating phenomena. They don’t accept that it comes from itself. The Madhyamaka school would say the butter lamp is dependent on many other factors. The Madhyamaka school would argue that if you’re saying that the butter lamp illuminates itself then it’s totally independent. The Madhyamaka school asserts, of course, that the butter lamp illuminates, but they accept that it depends on many other phenomena based on which, therefore, it illuminates. If it illuminated itself, the Madhyamaka school would argue, then also the darkness has to obscure itself. If there’s darkness, we can’t see the objects because it’s obscured by the darkness. We say the object is obscured because the darkness obscures these things that we can no longer see. But if the light bulb illuminates itself, then darkness must obscure itself. If darkness obscures itself, then it would follow that we cannot see darkness, but we can see darkness. Darkness doesn’t obscure itself because we can see darkness.Therefore, the Madhyamaka school says there’s no self-knower. They don’t accept the existence. The Prasangika school says there’s no self-knower.

Audience: Is the purified mind the Buddha mind or enlightenment? And if so, isn’t that not dependent on conditions?

Yangten Rinpoche: When we talk about a pure mind, as explained earlier, there are different types of pure minds. Pure minds is from the point of view of having eliminated coarser types of obstructions. We speak of the path of seeing, for instance. So, the path of seeing is a mind that has eliminated some of the coarser afflictions—the intellectually acquired afflictions. It’s pure of that. In particular, the subsequent kind of meditative equipoise that has eliminated these is said to be a pure mind, but pure is in relation to particular afflictions, particular obstructions, that have been overcome. Actually, the Buddha’s mind is the purest mind. The purest mind is a Buddha’s mind. Not every mind that is pure is that final pure mind or this ultimate final mind, this ultimate pure mind. But it doesn’t mean that it exists independently.

Even the Buddha’s mind is dependent on other factors. Even enlightenment doesn’t exist inherently. Whatever exists is dependent on other factors; it’s dependent on causes and conditions and so forth. In that sense, nothing exists. There’s not a single speck of phenomena, a single particle of dust, that could exist inherently. Anyway, so we’ll explain this more. So, verse 30 says that the proponents of yoga practices say that a pure mind effected through mastery of one’s own mind and through utter revolution of its state is the sphere of its own reflexive awareness. That is presenting the view of the Cittamatra school, a view that says that the mind exists truly because there’s this reflexive awareness, there’s this self-knower, that can establish this true existence.

Dividing moments of mind

And then verse 31 says:

That which is past is no more;

That which is yet to be is not obtained;

As it abides its locus is utterly transformed,

So how can there be [such awareness in] the present?

So, the Cittamatra are saying that phenomena exists truly, but here we’re refuting this by saying that we can divide the mind into different times in terms of the first moment, the second moment, etc. That which is the past of the mind is no more; that which is yet to be doesn’t exist yet—it’s not obtained. So, the locus of the present moment of time is utterly transformed. We can’t posit it if we take one mind, for instance, one consciousness.

We don’t need to talk about a pure mind or whatever kind of mind, just our present mind, our mind that exists moment-by-moment. The former moments of mind are gone. The future mind hasn’t arrived yet, hasn’t come into existence yet. So, when we talk about mind, we can only talk about the present mind. But actually, the present mind also can be further divided into a former moment and a later moment. One moment in time consists of a later moment and an earlier moment. So, you can divide any moment in time. With any moment in time, that one moment consists of a former moment, a later moment, and a moment that is in between. It always exists of another three parts—three moments in time. You can divide it at least into two parts: a former and a later moment. So, the present moment right now connects to the former moment and connects to past moments. The future moments connect to further future moments. And so basically, you can again and again divide each moment; you can divide it endlessly. There are always former moments and always later moments.

So, what is the exact present moment? It’s very difficult to posit an exact present moment. Also, when we talk about consciousness, it’s a continuum. We talk about a former continuum, a later continuum, a future continuum and so forth. We can think about a present continuum in that way. If we didn’t have a past moment, you couldn’t have a present moment. If there’s no future moment, there’s no present moment. The present is dependent on the past and the future. It’s not possible to have a present moment that is not dependent on the past and the future; that’s impossible. The present is dependent; it can only be the present if there’s a past and if there’s a future. Therefore, the present is dependent. It is posited on the basis of past and future. There’s nothing that doesn’t exist in relation to other phenomena.

Consider what we mean when we say “day and night.” If everything were daytime, would we really have daytime? If everything were the nighttime, would we really have nighttime? Nighttime and daytime are dependent on each other; they’re interdependent. In dependence on nighttime, you have daytime; in dependence on daytime, you have nighttime. To have daytime, you must have a different time based on which you can distinguish it from everything else. If all phenomena were daytime, how would we distinguish it from anything else? There wouldn’t be anything different in relation to which it would be daytime. Therefore, everything that exists can only exist in relation to something else.

Going back to the mind then, saying that there’s a smallest moment in time doesn’t make sense. Nagarjuna is really precious because he reintroduced the Madhyamaka view. So, there are a lot of very powerful reasonings that help us to understand how phenomena really exist. There are endless reasonings that Nagarjuna presented that prove there’s no true existence. For instance, does walking exist inherently or not? What is walking? When we walk we lift our right foot then we place it on the ground. Then we lift the other foot and then place that on the ground. So, it’s this kind of movement of the feet. If we say there’s inherent walking, we need to be able to point at something. And we can’t look at the place that the feet are placed on. No, it has to be the feet; it has to be that which moves.

When we place the foot on the ground, is that walking? Well, that’s not walking. When we lift the foot, is that walking? The time while the foot is in the air, is that walking? Even here the foot has parts. Which part of the foot is walking? The foot is walking; therefore, where is the walking on the basis of the foot? The foot has many different parts. It’s this solid object that is formed by many different parts. Which part is walking? Is it the front part? In relation to the front part, we say the upper part is walking and so forth. So, it’s in relation to these different parts that we say one does this and one does something else. But we cannot find something solid. When we say walking, walking is actually a movement. That which is moving is the foot. Is it the entire foot that is moving? Is just lifting the foot walking? We can’t say that just lifting the foot is walking because there needs to be a movement. There needs to be a movement in terms of going from one place to the next. One aspect has to go to a different aspect.

Therefore, is it the whole foot that is moving? And where does the movement come from? For instance, before you place the foot, the first part of the foot is already on the ground—the front part is already on the ground. Then the heel is not on the ground yet and so forth. So, which one is walking and which one is not walking? It’s difficult to really place something.

Also, when we talk about time, does a month exist? A month exists of many days. Where is one month? These 30 days, for instance, are described to be a month. So, on the first day of the month, has the first month come into existence? No, because the 30 days have not happened yet. Or after 29 days, the one month is gone. Or after the first day, you only have 29 days left. So the month is gone because there’s no month that has 29 days. Therefore, actually, when we just label one month on the basis of its path, that’s okay. It’s just an appearance of the mind. There’s no contradiction because it’s just imputed. It’s just labeled by the mind on the basis of labels and so forth. But if a month exists truly, we should be able to point at that one month. What is this exact month? As it says in this verse, that which is past is no more. As it abides, the locus is subtly transformed. So, where can be such an awareness in the present?

Refuting an inherent self

Then verse 32 says:

Whatever it is it’s not what it appears as;

Whatever it appears as it is not so;

Consciousness is devoid of selfhood;

[Yet] consciousness has no other basis.

Consciousness is the word for selfhood. Therefore, phenomena, the way they appear to us, don’t exist that way when it comes to the mind and the object. It seems that phenomena exist autonomously as if they existed in and of themselves. When we say the mind, it says later on also that the mind doesn’t exist truly. This self doesn’t exist substantially; it doesn’t exist truly. That’s what we’re doing here: we’re refuting this view of the Cittamatra school.

So, consciousness is devoid of selfhood. It’s selfless. Yet consciousness has no other basis. Now, the Cittamatra school says that the alayavijnana is the mind, is the person. So, in the Cittamatra school, you have this assertion of eight consciousnesses and the belief that the eighth consciousness—the alayavijnana or the mind basis of all—is the self. That is the person. It’s neither virtuous nor non virtuous; it’s a neutral kind of mind that is always present. But that is impossible. There is no basis because the mind doesn’t exist truly. So, how can you say that the alayavijnana or that the mind basis of all exists? That’s what verse 32 explains. Consciousness itself lacks true existence. It doesn’t exist truly. The self doesn’t exist truly, doesn’t exist inherently.

Then Verse 33 says:

By being close to a loadstone

An iron object swiftly moves forward;

It possesses no mind [of its own],

Yet it appears as if it does.

The magnet basically moves the iron objects around. It possesses no mind of its own. It doesn’t need a mind for the magnet to move things around. So, there’s no kind of volition. Yet it appears as if it does. It seems that there’s something truly there—like some kind of mind.

Then verse 34 says:

Likewise the foundational consciousness too

Appears to be real though it is false;

In this way it moves to and fro

And retains [the three realms of] existence.

Here, the mind that is responsible for samsara and nirvana is explained to be the foundational consciousness. It’s just our general mind. It’s the mind that perceives, the mind that attains liberation, the mind that is reborn in the lower realms. All this is the mind. That’s the foundational consciousness. That doesn’t exist truly. It appears to be real, but it is false. It appears to be real. It appears to be truly existent, but it doesn’t exist that way. And in this way, it moves to and fro and retains the three realms of existence. On the basis of this mind, we are reborn. For instance, from a previous life, we’ve been born into this life and we’ll be born in future existences. That’s how we cycle in samsara. Therefore, we continue to exist in samsara on the basis of the mind.

Verse 35 says:

Just as the ocean and the trees

Move about though they possess no mind;

Likewise foundational consciousness too

Move about in dependence upon the body.

This verse is taking the ocean and trees as an example. They move around. They do things. They move; they perform functions and so forth. That doesn’t mean that the foundational consciousness is the person just because it moves about. When we say the foundational consciousness is the person, the alavijñāya is the person, why are they the same then? That which is reborn is the self. Usually, the assertion comes from the fact that the Buddha says that that which is reborn is the self. And since consciousness is reborn, we say that consciousness is the self. That’s one of the main reasons why many philosophers say that consciousness is the mind.

The consciousness comes from a previous life, and it continues on to a next life. That’s what consciousness does. That’s what moves from life to life. It’s that which moves through the different lives. It’s that which appropriates the body, for instance. It takes a new body, so that goes from life to life. But that doesn’t mean that the foundational consciousness is the self or that it exists truly. The foundational consciousness moves from life to life, but it moves in dependence upon the body. Its basis is the body. We say, for instance, that the mental consciousness is dependent on the mental sense factor. It always needs a basis, a physical basis. But there’s not more to it. So, that’s how we say it moves. It’s because the foundational consciousness takes on the different body that we say it moves. For instance, the eye consciousness depends on the sense faculty or the sense power. On that basis, eye consciousnesses can arise.

We say there’s a difference between the sense faculty and the sense consciousness. They’re different. Maybe in English it sounds as if they were the same, but an eye consciousness does depend on the sense organ; it depends on the sense faculties. Likewise, the foundational consciousness also depends on a body. That’s just as the sense consciousnesses depend on the body, on the sense faculties, on the sense powers. Likewise, the foundational consciousness, the mental consciousness, depends on the body. It must have a physical aggregate. This is the basis for the foundational mind. In dependence on a different body, we say it moves. It’s not truly existent—it’s not a self that exists truly and that moves truly.

Exposing errors in logic

Then verse 36 says:

So if it is considered that

Without a body there is no consciousness,

You must explain what it is, this awareness

That is the object of one’s own specific knowledge.

When we say consciousness, it’s based on the body. It moves; therefore we say it moves between different lives. Without the sense faculty, without the sense power, there wouldn’t be any movement of the mind. There wouldn’t be any activity of the mind. The consciousness depends on the sense faculties—on the body and so forth—and on the external objects as well. Also, it depends on the previous moment and the immediately preceding consciousness. On the basis of that, we can say that a consciousness is active. It moves; it knows. It’s clear and knowing.

We say that consciousness is something that clearly perceives something. How does it do so? It does so in dependence on the sense faculty or the sense power. It depends on the object and the immediately preceding awareness. When we take an eye consciousness that perceives a physical form, we need a previous moment of awareness. Without a previous moment of awareness, you couldn’t have a present awareness. Therefore, in dependence on all these different factors, our mind perceives objects. It does so in dependence on other things. It exists in dependence on other phenomena. It exists in dependence on any other objects. Therefore, it’s an independently arisen phenomenon. Because it’s an independently arisen phenomenon, that’s its nature. Therefore, the mind is clear and knowing.

It’s clear and knowing, so how can you say that you need a self-knower—a something that knows itself? For instance, the self-knower knows itself, or it exists in and of itself. The Cittamatra school would say that the mind exists truly. It is clear, and it’s a clear and knowing entity. Well, it decides that it’s a clear and knowing entity because the mind exists in and of itself. The self-knower that is a part of it decides, basically. It’s like it decides itself that it is a clear and knowing faculty. It exists like that in and of itself. But actually, that’s not true. There are so many other objects, so many other phenomena, on which it depends. That’s what the Madhyamaka school would argue, the Prasangika school would argue. That doesn’t make sense. It depends on so many other objects. It’s impossible that it exists in and of itself as a consciousness, as a clear and knowing entity.

Verse 37 says:

By calling it specific awareness of itself,

You are asserting it to be an entity;

Yet by stating that “it is this,”

You are asserting it also to be powerless.

If there is this self-knower with a specific awareness of itself, which is a part of that mind, then you’re asserting it to be an entity. Yet, by stating that it is, you’re asserting it also to be powerless. Here, entity means truly existent. An entity is a permanent phenomenon. So, it’s kind of an independent, truly existent entity. When you are speaking of the self-knower, it establishes itself. If it establishes itself, it knows itself. Therefore, when we think about this, that’s empty. That’s an empty kind of statement. So basically, you can’t say anything else. You’re just asserting it is also powerless. It shows us that you can’t answer this properly. The self-knower knows itself. It doesn’t need another awareness. That shows your inability to really answer this properly. Since by stating that it is this, you’re asserting it also to be powerless. So, your explanation is powerless or empty, basically.

What establishes the self-knower? It establishes itself. That is powerless, basically. So, what establishes the mind? You’re not able to really explain this. You’re not able to prove that the mind exists truly. This is what it means here when it says it’s powerless. You’re arguing it’s powerless. In the Cittamatra school, they say that the mind establishes itself. Really, what this means is that the Cittamatra school can’t really establish the existence or the true existence of the mind.

Then verse 38 says:

Having ascertained oneself

And to help others ascertain,

The learned proceeds excellently

Always without error.

First, we need to really, really understand the situation. Then when we understand how phenomena really exist, we can explain it. So, how does the mind really exist? Once we can understand it then we can help others to ascertain or understand that as well. Then we can understand things without any error. But you don’t have enough self-confidence. You’re just explaining something that doesn’t have any real foundation. It’s like doing it out of despair in the sense of not being able to properly explain it. That’s why you come up with this explanation. But you can’t explain it without a mistake. You can’t explain it in a way that is free from error. That’s what verse 38 says.

Then verse 39 says:

The cognizer perceives the cognizable;

Without the cognizable there is no cognition;

Therefore why do you not admit

That neither object nor subject exists [at all]?

So, you need an object. In the dependence on that which is cognised, you say that is a cognition. And because it’s a cognition, there’s something cognisable. They exist in dependence on each other. There’s a mutual dependence of cognisable and cognition. Therefore, when we say the mind and the self-knower, the self-knower is that which cognises and the object is the cognisable. Then it’s actually said to be one mind. The Cittamatra asserts that the self-knower is part of that which it knows. But you can’t have one object that is the cognition and the cognisable in relation to the same object. It cannot be that which cognises the cognisable but then also be the cognisable that is perceived by the cognition. It can’t be in relation to the same object. That’s impossible that there’s one mind that in relation to itself is both the cogniser and the cognisable. The Prasangika school says that this is not possible.

They give the example of a knife. If you have a knife, a knife can’t cut itself. No matter how sharp a knife is, it cannot cut itself. Or, for instance, an athlete: they cannot stand on their own shoulders. Although they’re very strong, they can do anything, but they can’t stand on their own shoulders. There are a lot of examples that refute the self-knower. No matter how clear an eye consciousness is, an eye consciousness can’t see itself. These are some of the analogies that the Prasangika school gives. So, in dependence on mind, we say there’s an object. The cognisable is dependent on the cognition that cognises this object and vice versa. What establishes the mind? The cognisable is a cognisable in relation to cognition. That’s what the Prasangika school says. So, how can we say the cognisable exists? What establishes it? It’s the cognition. And what establishes the cognition? We don’t need another cognition that now establishes the cognition. We don’t need something else. What establishes the existence of cognition? It is the object—that which it cognises. It’s the object that it perceives, the object that it apprehends.

So, the cognition cognises something. And on the basis of that, we can say cognition exists. So that which establishes cognition, that which establishes the existence of cognition, it’s not another mind, but it’s an object. The cognisable depends on the cognition, and the cognition depends on the cognisable. Because it cognises something, because it has an object, we can say that cognition exists. In that way, we can say that establishes its existence. The cognition itself doesn’t cognise itself. Therefore, the cognisable is dependent on the cognition, and cognition is dependent on the cognisable.

But it’s not just that. We say that they depend on each other. So, cognisable and cognition are mutually dependent. The word used here implies there’s something that the mind is conscious of. In Tibetan, the word literally translated means knower. So, you can translate consciousness as knower, because it implies that it knows something. It implies that something is cognised. In Tibetan, mind and cogniser are different, mind and cognition are different. They’re different words. If there were no cognisables, no objects to be cognised, there wouldn’t be any cognition. If there were no cognition, there wouldn’t be anything cognisable. If there was nothing cognisable, there wouldn’t be a cognition. We say something is cognisable, because there is something that cognises it. So, there must be a cogniser—a consciousness that does so.

Here’s another example from the ninth chapter of The Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. Consider a father and son: you couldn’t talk about a father unless he had a child. And also, you can’t have a son or a daughter if there are no parents. So, we say that in dependence on the parents, you have a daughter and son. And because someone has a daughter or a son, we can say that they are a father or mother. They’re dependent on each other. Cause and effect are just like that. That which creates something and that which is created, cognition and cogniser—they’re all dependent on each other.

For instance, when we talk about food, in dependence on us, this is food. This is in relation to us being human. In relation to us as human beings, we eat certain foods. So, it’s in dependence on us as humans. It’s dependent on us. But if there were no sentient being to eat it, then it wouldn’t be food. If it were in and of itself food then it would be food for everyone. But actually, that’s not true. For instance, meat is something we can eat, but there are many other sentient beings that wouldn’t eat meat. For them, therefore, meat is not something edible. It’s the same thing with sweet foods. They are not food in relation to certain animals. Certain fish, for example, wouldn’t eat sweet food. So, when we say food, food exists in relation to other phenomena. It depends on other phenomena.

When we say iron or stones, are they food or not? No one would say they’re food. So, stone is not food. And what about something rotten or something moldy—is that food? No, we wouldn’t say it is. But there are animals who eat old, moldy meat. For them, it’s food, but for us, it’s not. In the scriptures, they talk about certain animals also who eat stones and iron and so forth. Therefore, it’s food. It’s possible that there were particular animals, for instance, that ate those certain substances. Even scientists talk about how there are certain types of animals that no longer exist, that are extinct now. There are a lot of things that we wouldn’t consider to be food. We couldn’t digest, for instance, wood. We can’t eat wood, but there are certain insects, like little worms, that eat wood. Therefore, there’s nothing from the side of the object that says it’s food. It depends on the being who eats it. It is the same with cognition and cognizable. This is actually true for all phenomena.

Merely labeled phenomena

Then verse 40 says:

The mind is but a mere name;

Apart from it name it exists as nothing;

So view consciousness as a mere name;

Name too has no intrinsic nature.

So the mind is a mere name; it’s merely labeled. It doesn’t exist intrinsically. Apart from its name, it exists as nothing. Even that label we apply, that term or label we use to refer to something, has no intrinsic nature. If the object doesn’t exist inherently, then the label that is applied to the object cannot exist in here inherently. They depend on each other. So, the label and that which is labeled depend on each other. They are mutually independent. When we say subject and object, they exist in dependence on each other. Consider “permanent” and “impermanent”: the dependence here is different, but still, permanent and impermanent depend on each other.

The mountain over here, the mountain over there, wet and dry, cause and effect—all of these are mutually dependent. If we think about it, there are many examples of phenomena being mutually dependent. It says in The Precious Garland that the form is mere name. And so the same applies to the different elements. Even mere label doesn’t exist. The mere name doesn’t exist. This is what The Precious Garland says. And this is true for all the other factors that make up a person. Even the mere name doesn’t exist inherently; therefore, all phenomena lack inherent existence. They’re merely labeled. They’re merely posited on the basis of the mind—in dependence on the conceptual mind and the label.

All these objects that appear, such as the light rays, the rays of the sun, we say they’re appearances. So, because of these appearances, we’d say they illuminate everything; they enable us to see things. These objects appear to us; these rays of light appear to us. But an owl can see in the darkness. In the darkness it perceives things very clearly while in the light it doesn’t see as clearly. It’s very different for the owl; it’s very different. Or these sense consciousnesses we have enable us to perceive the different sense objects: “This is form. This has a color. It has a shape. There’s a building.” And so forth. All these different sense objects, all the objects that we desire—form, smell, sound and so forth—they’re all the objects we perceive. They seem to exist objectively; they seem to exist inherently. We have a sense that everyone perceives the same way that we perceive because of our sense of an objective existence. But that’s not the case. That’s what it says in this verse: this is not true.

For instance, when we talk about celestial beings of the form realm, they don’t depend on the sense objects. They depend on the happiness, the bliss, that arises from their concentration. They are not sustained by the sense objects the way we are sustained by the sense objects. They don’t really interact with the sense objects. It’s really the mind, the mental element, that sustains them. So, it’s different for these celestial beings. And then when we talk about the celestial beings of the formless realm, there are a lot of formless beings, but they have no form. They have only concentration—this one-pointed concentration. And their feeling is just a neutral feeling. So basically, we can say they exist in this realm where there are no physical objects.

We speak about different kinds of worlds or the different kind of realms—the desire realm, and so forth. There’s a story that illustrates this from the past. There was a woman who had a husband. She had a good relationship with her husband and then the husband died. She was so sad, and she missed her spouse so much that the spouse kept appearing like in a dream. Actually the spouse had died, but she always had this appearance of him like in a dream. He always appeared. She talked to him. He appeared to her. There was a sense that the late husband was actually there. This shows that our mind can create these mistaken appearances, and so this is similar. Our mind creates a lot of mistaken appearances. The way phenomena appear around us—everything that appears to us, all the objects around us—seem to exist in and of themselves. It seems there’s this permanent, stable, solid environment. We have a sense that what we perceive, everyone else also perceives because of the sense of this objective reality out there, but that doesn’t exist.

For instance, this planet we live on is so big that when we take a plane we have to sometimes travel for 24 hours. So, there’s a sense that this world is so big, but the sun is so much bigger than planet Earth. Likewise, when we talk about Mars and Neptune and Jupiter and so forth, these different planets that are part of our solar system, they are much smaller actually. The moon is smaller than the earth and then the sun is so big. All these different planets that revolve around us are actually so huge and then think of the whole universe and the different galaxies. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, consists of so many stars and it seems planet Earth is so small in comparison. We’re so small actually—so tiny really. It’s like we’re a little insect in relation to this entire world, this entire world system. We have a sense that we’re so big, and we’re so important, but in actuality, in relation to all that, that’s not the case. Everything exists in mutual dependence, so everything can only be posited in relation to something else. Nothing exists in and of itself.

No inherent existence

Verse 41:

Either within or likewise without,

Or somewhere in between the two,

The conquerors have never found the mind;

So the mind has the nature of an illusion.

So, this verse is saying that the mind itself doesn’t exist; mind cannot be found. Of the external and internal, we can’t really find anything that is the mind, so it doesn’t exist the way it appears.

Then verse 42 says:

The distinctions of colors and shapes,

Or that of object and subject,

Of male, female and the neuter—

The mind has no such fixed forms.

The mind has no colors; it has no shapes. Then when we talk about object and subject, or object and the apprehending factor, we can’t say that one mind is the same in relation to the same thing. It’s not. Also, we can’t say the mind is male, female or neutral. The mind doesn’t have these characteristics. We usually describe the gender of a person or the sex of a person on the basis of the body, so the mind has no such fixed form.

Verse 43:

In brief, the Buddhas have never seen

Nor will they ever see [such a mind];

So how can they see it as intrinsic nature

That which is devoid of intrinsic nature?

So, phenomena don’t exist intrinsically; they don’t exist inherently.

Questions & Answers:

Audience: How do you use tenets—for example, partless particles, mind only and so forth—in our daily lives to subdue the mind?

Yangten Rinpoche: When we talk about subduing the mind, it’s really wisdom that’s the main aspect that helps us to subdue the mind. There’s nothing more profound than applying wisdom. So, for instance, in the Pramanavartika, it says that through love and compassion they cannot really eliminate the self-grasping mind; it’s only wisdom that can reduce our self-grasping. Of course, love and so forth can affect our afflictions, but they cannot really eliminate them. For instance, I talked yesterday about how we can’t understand past and future lives without wisdom. When we really understand past and future lives, if we really think of many, many lifetimes, it really affects our mind. It really changes our attitude so that when we think about problems in this life, we understand that “Well, it’s just one life.” It becomes insignificant when we reflect upon all these other lives. Once we understand that we’ve existed for so long and we will continue to exist, then this one life is not as important. We won’t be so obsessed with this one life.

If you have a sense that there’s only one life then if we’re not successful in this life, we’re desperate. We will despair because there’s only one life, so that’s the only chance we have. But if we reflect on other lives it’s different. Selflessness is extremely important to reduce our afflictions. Selflessness is so important, but there are many who disagree with selflessness. Actually understanding the lack of intrinsic existence is the only way is to overcome the afflictions, but there are a lot of philosophers who say that it’s impossible that phenomena lack intrinsic existence. They say that phenomena must exist intrinsically; they must exist inherently. The external phenomena must exist in that way because of the physical world, for instance. There are many paths that form this world, so there must be some fundamental building block, something very solid and concrete that we can point to. Otherwise, how can this very solid world come into existence? That’s their argument.

They say that there must be particles, there must be very solid objects—truly existent objects. In the Prasangika school, the lack of intrinsic existence is the superior reasoning. In this text, Nagarjuna says that selflessness or the lack of intrinsic existence is the superior means to overcoming the afflictions. And by actually understanding that there are no partless particles and so forth, then we can understand emptiness better. You have to refute so much to really understand that phenomena don’t exist inherently, to understand that external objects don’t exist truly, to understand that the mind doesn’t exist truly, to understand that the mind is not the self. All of this needs to be refuted. If we don’t refute that, we can’t really fully understand this very profound concept of emptiness. These are all part of understanding emptiness.

When we say refute, we’re not saying that out of attachment we’re trying to refute it. Instead, we’re applying reasoning in order to understand that inherent existence is just impossible. All these understandings of these different philosophical tenets, these different concepts, they help us to understand emptiness.

Audience: Can you please explain why conventional bodhicitta is a prime mind or primary mind rather than a mental factor?

Yangten Rinpoche: In the first chapter of the Abhisamaya-alamkara, The Ornament for Clear Realization, it talks about the mind having two aspirations. So, that conceptual conventional bodhicitta is associated with two types of aspirations, and it says very clearly that it’s a main mind. We speak of it as a main mind because in the different commentaries it just says that it’s associated with particular aspirations. We always speak of something being associated with a mental factor from the point of view of being a main mind, so here we speak very clearly about the aspiration to become enlightened. That is the aspiration of the main mind—which is bodhicitta—that it’s associated with.

When we distinguish between mind and mental factors, or primary minds and mental factors, we distinguish between them by saying that which merely experiences its object, that which is a mere clear and knowing entity, is the primary mind. On the basis of that, then we have these different functions: having the aspect of abiding with the object, of remembering the object, of discerning the object. From the point of view of the different functions, we talk about mental factors. Mental factors are not like different solid objects that come together. That’s not what it means. So, for instance, when we have an offering to the lama, like in the Lama Chöpa practice or the Guru Puja, then you offer these different objects. This is not what it means to have mind and mental factors—like many different objects coming together. It’s just talking about it from the point of view of the function. These different functions are described differently, so they’re actually one nature. Main mind and mental factors are one nature.

When we have a mirror, for instance, it reflects objects, so it has this reflecting nature. Objects can be reflected in this object, and then there are these different reflections: something yellow can be reflected, something white can be reflected, something red can be reflected. It has all these different aspects. You can’t really separate them from the mirror. Therefore, it is said in the scriptures that it’s a main mind and it’s not a mental factor.

Audience: You said that based on reducing attachment, our understanding of reality will increase. But how?

Yangten Rinpoche: The meaning here of reducing attachment is not like reducing things as in throwing something away. It’s not like pulling out the hair on our head. Rather, when we see something as really amazing, if we exaggerate the positive qualities of something, then we become attached. So, if we have attachment, we can analyze whether or not it really does benefit us. We need to analyze whether the way phenomena appear to us when there’s attachment is really in accordance with reality. Sometimes things benefit us but sometimes they don’t, so everything has so many different aspects in relation to these different attributes. So actually, if we see the thing for what it is then we can reduce attachment. When we reduce attachment then we understand how phenomena exist. Therefore, having reduced attachment then we can think about these objects that we perceive: “Oh, so now there’s a desire to own this object, but do I really need it?” We are able right away to analyze, so we reduce the attachment. Then we can apply this to other things. So, we can go in accordance with reality. We can proceed based on reality. That’s what I meant previously. We reduce attachment. It helps us to understand things better.

Audience: If there is no self, who can be liberated and who can reach enlightenment?

Yangten Rinpoche: When we say there’s no self, the meaning of that is that there’s no independent self; there’s no inherent self. That’s like this extreme kind of self. Of course there is a self that attains liberation, that experiences happiness, that accumulates positive and negative karma. There’s someone who’s active; there’s someone who eats; there’s someone who asks questions; there’s someone who answers. The person who answers is the self. That which eats is the self. That’s the I, so that’s what we say is the self. This is the self that exists without analyzing it. It’s merely labeled on the basis of name and conceptual mind. So, it’s a mere appearance: it merely appears to the mind. It’s just labeled; that’s how we say it exists. We can say it exists because it’s merely labeled. It merely appears; therefore it exists. Being a mere existence, it doesn’t exist beyond being merely labeled, being merely designated. It doesn’t exist in and of itself. That would be in contradiction to reality or in contradiction to logical reasoning.

Nothing can exist in and of itself. There’s nothing that’s very concrete; there’s nothing that you can exactly point at to say “That is its actual essential existence, existing in and of itself and inherently.” It doesn’t exist that way. Nothing exists that way. Lama Tsongkhapa talks about that. When analyzing how phenomena exist, we say first they have to be known by a conventional mind. Everything has to be known by the mind. It has to be known by consciousness; it has to be perceived by consciousness. This is the first aspect. So, for instance, the external world, this environment, our society—this is perceived in general by mind, and there’s no conventional valid cognizer that contradicts it. For instance, when we perceive a snake—when we see a snake body moving—there’s no other valid cognizer that contradicts this being a snake because it is a snake. Now it’s possible that we perceive a speckled rope that looks like a snake as a snake, but then another conventional valid cognizer contradicts that in the sense that when we analyze it, we come to know that it looks to be a snake, but it’s not a snake.

So, we can analyze whether this object is a snake or not. Therefore, for it to exist, it cannot be contradicted by a conventional valid cognizer, and also it cannot be contradicted by ultimate analysis. When it comes to the snake, if we analyze whether it exists truly or not, whether it exists inherently or not, that is contradicted by ultimate analysis. Whatever exists has to be perceived by a conventional mind; it cannot be contradicted by a conventional valid cognizer, and it cannot be contradicted by ultimate analysis. In that way, we can posit whether something exists or not. We can determine whether it’s existent or not. Therefore, with regard to the self, here we say it doesn’t exist in and of itself. But when we don’t engage in ultimate analysis then there’s some conventional self.

When we speak about certain wrong views that are intellectually acquired, that have arisen because of different philosophical views, they also give rise to afflictions. This is the explanation you find in the text that there are certain wrong views that create suffering—innate ones and intellectually acquired ones.

Audience: It’s said that you only realize emptiness directly once you’re already on the path of seeing on either the hero vehicle or the bodhisattva vehicle. Why can’t you realize emptiness first and then decide whether you want to be an arhat or bodhisattva? Why do you have to choose your vehicle first?

Yangten Rinpoche: In the Tibetan language it says that the vehicle comes first. There’s nothing to choose, basically. It won’t just come on its own without choosing. Why? Because it’s dependent on our thoughts. It’s dependent on our attitudes. So actually, when we think about something, there are four stages. If we don’t think of the future life, for instance, if we just think of this life, then this is like the ordinary worldly attitude of just thinking of this life. This is how we usually live. This is how we live our lives. We just think of this life. Or we can think of the future in the sense of there’s more than this life. There may be a future life, so where will I be reborn? Maybe I’ll be reborn as an animal, for instance, or a preta being or a hell being. That’s possible. There’s this possibility. In those cases, I’ll have a lot of problems. Therefore, based on that, I have to do something. I have to engage in virtuous action so I won’t be reborn in these lower realms. That is the attitude of a person of smaller spiritual aspiration. And then beyond that, if we think about this further, of course being reborn in lower realms is dangerous. But even if I’m reborn as a human being or as a celestial being, I’m still under the control of the afflictions. I’ll still have ignorance and attachment and aversion in my mind. Therefore, I will still have a problem.

Right now, I’m a human being. We know what it’s like to be a human. We experience it. It’s not easy to be a human being. It’s definitely not easy to live as a human. So actually, I’m still under control of my afflictions. Therefore, I have to overcome my afflictions. That kind of wish to overcome the afflictions is the attitude of a person of middling spiritual aspiration. And then I need to consider other sentient beings who are even more precious than the mother of this lifetime. All sentient beings have been so kind, and so I need to work for the benefit of all sentient beings to help them to overcome their afflictions. To be able to help them to do so, I need to become a Buddha. I need to achieve a state that is totally free from any suffering, from any afflictions, from any kind of limitations. That is possible. It’s possible to become a Buddha. So, I want to become a Buddha. This is the highest aspiration. These are the three aspirations.

Without these three aspirations, why would we work towards understanding emptiness? Consider selflessness, for instance: why should I have an interest in selflessness? We need to think about it in the sense of whether it’s beneficial or not. Does self-grasping harm me or not? If we have self-centeredness, we have to first recognize self-centeredness or self-grasping. Once we understand self-grasping, then we can understand that the self. We need to understand that the self-grasping mind is not in accordance with reality. Then, based on having understood that it’s not a correct mind, then we can continue from there to a deep understanding of selflessness.

And once we want to overcome this, once we realize we don’t want this self-centered or self-grasping mind, then we want to be free from it. That’s renunciation. And once we have renunciation, we enter a path. So, it’s just a natural consequence of this train of thought that leads us to realizing emptiness.

Part 2 in this series:

Part 4 in this series:

Yangten Rinpoche

Yangten Rinpoche was born in Kham, Tibet in 1978. He was recognized as a reincarnate lama at 10 and entered the Geshe program at Sera Mey Monastery at the unusually young age of 12, graduating with the highest honors, a Geshe Lharampa degree, at 29. In 2008, Rinpoche was called by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to work in his Private Office. He has assisted His Holiness on many projects, including heading the Monastic Ordination Section of the Office of H. H. The Dalai Lama and heading the project for compiling His Holiness’ writings and teachings. Read a full bio here. See more about Yangten Rinpoche, including videos of his recent teachings, on his Facebook page.