Researching the bhikshuni lineage

The September 2020 IMI (International Mahayana Institute) e-news included an extract from a teaching about Sangha and gelongmas that Lama Zopa Rinpoche gave in Holland in 2015. This article raised a number of questions and points for reflection regarding the gelongma/bhikshuni ordination. As someone who was very fortunate to receive this ordination (in 1988), I have some experience in this area, and I would like to offer a few responses and additional points to reflect on.

The history of bhikshunis

One question that Tibetans have been concerned about is whether the bhikshuni ordination in the Chinese and other East Asian traditions has existed in an unbroken lineage since the Buddha’s time. A number of people have researched this and concluded that it can be traced back to the Buddha. One such person is Ven. Heng Ching, a Taiwanese bhikshuni and professor at National Taiwan University, who has published a research paper on the history of the bhikshuni lineage.1 For those who may not have the time to read her paper, here is a brief history from the Buddha’s time until today:

- Several years after starting the Sangha of bhikshus (gelongs), the Buddha ordained the first bhikshuni, Mahaprajapati Gautami (his stepmother and aunt). Shortly afterwards he authorized his bhikshus to ordain 500 other women from the Shakya clan who wished to become nuns.2 Mahaprajapati and thousands of other female disciples became arhats by practicing the Buddha’s teachings and thus freed themselves from cyclic existence and its causes.

- The order of Buddhist nuns flourished in India for fifteen centuries after the Buddha’s time; there are even accounts of bhikshunis who studied at Nalanda Monastery in the seventh century.

- The bhikshuni lineage was brought to Sri Lanka in the third century BCE by Sanghamitra, the daughter of Emperor Asoka. She ordained hundreds of women as bhikshunis, and the Bhikshuni Sangha continued to flourish in Sri Lanka until the eleventh century CE.

- How did it come to China? The ordination of bhikshunis began in China in 357 CE, but initially it was given by bhikshus alone. Later, in 433 CE, a group of Sri Lankan bhikshunis traveled to China and, together with Chinese and Indian bhikshus, conducted a dual bhikshuni ordination for hundreds of Chinese nuns. Some people doubted whether the earlier ordinations given by bhikshus alone were valid, but Gunavarman, an Indian master living in China who was an expert in Vinaya, said that they were, citing the case of Mahaprajapati.3

Thus the bhikshuni lineage that originated with the Buddha and was passed down for many centuries in India and Sri Lanka merged with an already existing lineage of bhikshunis who had been ordained in China by bhikshus alone. From that time on, the Bhikshuni Sangha flourished in China and later spread to Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan, and continues to the present day.

As of 2006, there were over 58,000 bhikshunis4 in these countries and around the world. They include around 3,000 Sri Lankan bhikkhunis (the Pali term for bhikshuni). Although full ordination for nuns thrived in that country for fourteen centuries, it disappeared in the eleventh century due to various adverse conditions such as wars, famine, and colonization. But it has now reappeared: several Sri Lankan women received full ordination from a dual sangha at Hsi Lai Temple, California, in 1988, and another thirty received it in two dual ordinations held in Bodhgaya, India in 1996 and 1998. They thus became the first Sri Lankan bhikkhunis in nearly 1,000 years. Since that time bhikkhuni ordinations have been held in Sri Lanka itself, and the number of full-ordained nuns has increased to 3,000. There is also a growing number of bhikkhunis in Thailand—now numbering nearly 200—as well as other Theravada countries such as Bangladesh, and in many western countries.

It is clear that His Holiness the Dalai Lama and other high Lamas acknowledge the validity of the Dharmaguptaka5 bhikshuni ordination. I know several nuns who have been advised by the Dalai Lama to take this ordination, and in a statement he issued during the 2007 International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha (held in Hamburg, Germany), His Holiness said: “There are already nuns within the Tibetan tradition who have received the full Bhikshuni vow according to the Dharmaguptaka lineage and whom we recognize as fully ordained.” He also said, “I express my full support for the establishment of the Bhikshuni Sangha in the Tibetan tradition,” and gave a number of wise and compassionate reasons for his support.6

Furthermore, the majority of the lamas who attended the 12th Religious Conference of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism and the Bon tradition organized by the Department of Religion and Culture in Dharamsala in June, 2015, agreed that those nuns who wish to become fully ordained can take the bhikshuni vow in the Dharmaguptaka tradition, and advised that the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya texts be translated into Tibetan. This indicates that they, too, acknowledge the validity of this tradition, i.e. that nuns ordained in this tradition are genuine bhikshunis. However, this sangha council was still unable to make a clear decision about how to bring the Mulasarvastivada bhikshuni ordination into the Tibetan tradition.

Viewpoints of Chinese masters

Zopa Rinpoche mentioned in his teaching that he once met an abbess in Taiwan who told him that they didn’t have the lineage from the Buddha. I wanted to contact this abbess to ask what was her reason or source for saying this. I wrote to Rinpoche and several others who were with him during his visits to Taiwan, but no one could recall the name of the abbess or anything about that meeting. I wrote to Ven. Heng Ching, the author of the above-mentioned research paper, and asked if she knows anyone in Taiwan who has doubt about the validity of the bhikshuni lineage, and she replied that she does not know any monastic or Buddhist scholar in Taiwan who doubts its validity.

However, her research paper mentions a Chinese master, Ven. Dao Hai, who believed that the bhikshuni lineage from the Buddha had been broken during a period of Chinese history (starting in 972 CE) when an edict of the emperor forbade bhikshunis to go to bhikshus’ monasteries for ordination. During that time, bhikshuni ordinations were conducted by bhikshunis alone, which is not a correct procedure. But Ven. Heng Ching refutes his assertion because she has found records indicating that that edict lasted only a few years—not long enough for the lineage to be broken—and dual ordinations started again in 978. In spite of his doubt, Ven. Dao Hai clearly accepted the bhikshuni ordination as valid; he himself ordained bhikshunis on numerous occasions and also gave Vinaya teachings to many bhikshunis. He passed away in 2013.

Thus it seems that the majority of Taiwanese Buddhists accept the validity of the bhikshuni ordination—that it can be traced back to the Buddha. Western nuns who have visited Taiwan have noticed that the bhikshus and lay Buddhists are highly respectful and supportive of the bhikshunis, both for their practice and for sustaining and spreading the Dharma.

Dual vs. single ordination

The question of dual vs single ordination of bhikshunis is complicated—but the Vinaya itself is complicated, like a legal code that can be interpreted in different ways. Some Tibetans have the view that only a dual ordination is valid, and since that type of ordination has not always been given in the Chinese tradition, they doubt the validity of the entire lineage. But as stated above, single ordination—i.e. ordination of bhikshunis by bikshus alone—is considered valid in the Dharmaguptaka tradition; this was the opinion of the fifth-century Indian Vinaya master Gunavarman, and it was re-confirmed by the seventh-century Dharmaguptaka master Dao Xuan. Furthermore, there are passages in the Vinaya texts of both Dharmaguptaka and Mulasarvastivada indicating that bhikshuni ordination given by bhikshus alone is valid. For example, the Mulasarvastivada text Vinayottaragrantha (‘Dul ba gzhung dam pa) says that if a shikshamana (probationary nun) is ordained through the legal act of a bhikshu, she is considered fully ordained, even though those who ordained her committed a minor infraction. This means that even in Mulasarvastivada, bhikshunis can be ordained by bhikshus alone, although the Tibetan Vinaya masters have not yet come to an agreement about how to implement that. Nowadays in Taiwan and other Asian countries, there is an effort to ensure that bhikshuni ordinations are conducted with the requisite number of both sanghas.

Reasons for taking bhikshuni ordination

Another question raised by Rinpoche is: why take this ordination?7 Some people may think it is unnecessary, because Buddhism flourished in Tibet since the seventh century without having the gelongma ordination. Women in the Tibetan tradition who wish to live a monastic life can receive the getsulma/novice ordination, as well as bodhisattva and tantric vows, and then dedicate their life to learning and practicing the Dharma; many are probably content with that. But I can’t help but think that if the gelongma/bhikshuni ordination had been developed in Tibet and had received the support of the lamas and monks, most Tibetan nuns would probably have chosen to take it. It was the ordination originally given by the Buddha to his female followers, whereas the novice ordination was introduced later for children.8 There is also another ordination—probationary nun (Skt. shikshamana; Tib. gelobma)—that women need to keep for two years prior to taking bhikshuni precepts.

The Buddha’s teachings explain a number of reasons why keeping bhikshuni precepts is beneficial for our spiritual development: for example, it enables us to train our body, speech, and mind more diligently; to purify negativities and accumulate merit; to eliminate obstacles to concentration and wisdom; and to attain the long-term goals of liberation or Buddhahood. Taking and keeping the bhikshuni precepts is also important for the continuation of the Dharma in the world, and to benefit the Buddhist Sangha as well as society in general. The bhikshuni sangha is one of the four components of the Buddhist community—bhikshus, bhikshunis, upasakas, and upasikas—so if one of these groups is missing, the Buddhist community is not complete and a central land, one of the conditions of a precious human life, is missing.

It is undeniable that, even before he began to teach, the Buddha had the intention of starting orders of bhikshus and bhikshunis. In the Pali Canon, there are accounts of an incident that took place shortly after the Buddha’s enlightenment, when Mara encouraged him to pass into Parinirvana then and there. But the Buddha replied that he would not attain his final passing away “until my bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, laymen and laywomen, have come to be true disciples — wise, well-disciplined, apt and learned, preservers of the Dhamma, living according to the Dhamma, abiding by appropriate conduct and, having learned the Master’s word, are able to expound it, preach it, proclaim it, establish it, reveal it, explain it in detail, and make it clear…”9 A similar account can be found in the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, in the Tibetan canon.10

However, as Rinpoche emphasized in his teaching, it is essential to have the correct motivation: anyone interested in taking these precepts should sincerely wish to learn and keep the precepts to the best of their ability, in order to strengthen and deepen one’s own practice and to benefit others. And no one should feel pushed to take the full ordination—just as some monks are content to remain novices their entire life, some nuns may choose to do likewise. On the other hand, if a monk or nun sincerely wishes to take full ordination with the correct motivation—i.e. the determination to be free from cyclic existence—is there any reason why they should not be supported?

At a meeting of the IMI Senior Sangha Council in August 2017, the issue of IMI nuns taking gelongma ordination was discussed, and we reached the conclusion that the decision to take either gelong or gelongma ordination is completely a personal, individual choice; no opinion of IMI on this is needed. Ven. Roger added that if nuns wish to receive training and support, it is valid for the IMI to support them, and that if they take ordination in the Chinese tradition, they should take care of their vows and perform the rituals according to that tradition; this is valid. Therefore, this indicates that IMI policy has no objection to nuns taking the bhikshuni ordination if they so wish.

Is it difficult to keep so many precepts?

The last question I will deal with here is whether or not it is difficult to keep so many precepts (in the Dharmaguptaka tradition there are 348, and in the Mulasarvastivada tradition there are 364 or 36511 ). In my experience, only a small number of the precepts are challenging to keep. Quite a few of our precepts are the same as those kept by gelongs/bhikshus, such as not handling money, not eating after mid-day, and so on. The vinaya texts explain exceptions to many of these as well as practices for purifying those we do transgress. So we try our best to be mindful of the precepts we hold, have respect for them, keep them to the best of our ability, and confess any transgressions we make.

It is important to understand the reason and purpose of each precept and to observe it accordingly. Some precepts need to be adapted to our contemporary situation. For example, one precept prohibits traveling in a vehicle. In the Buddha’s time it would have been inappropriate for monastics to travel in vehicles because only wealthy people did that, but nowadays everyone travels in vehicles! Another example is a precept that includes “not going to a village alone.” The purpose of this precept is protection from danger such as assault; it doesn’t mean a bhikshuni can never go out alone to run an errand or travel alone on a train or plane. Ven. Wu Yin, a Taiwanese Abbess with over sixty years’ experience living in bhikshuni vows, explains, “The focus of this precept is safety, to prevent bhikshunis from encountering dangerous situations. If no companion is available, a bhikshuni may go out alone at safe times and in safe places. However, she should avoid travelling alone late at night or in unsafe areas.”12

Being able to keep the precepts depends a lot on personal integrity, but also on one’s living situation. It’s more difficult to keep the bhikshuni precepts while living alone or in a lay community, and much easier to keep them while living with other bhikshunis. To experience the greatest possible benefits of full ordination—whether one is a nun or a monk—it is best to live in a monastery. Living with a community of four or more fully ordained monastics enables one to do certain important Vinaya activities, such as the bi-monthly rite for purifying and restoring our precepts (sojong), and is a huge support for keeping the precepts and preserving the simplicity of the monastic way of life.

I have been staying at Sravasti Abbey in Washington on and off for the past few years, and I find this to be an ideal situation to live as a bhikshuni. At present there are twelve Western and Asian bhikshunis, four nuns in training to become bhikshunis, and a number of women who wish to join the community and start training once the pandemic dies down. The community regularly performs the three monastic rites—sojong (poṣadha), yarne (varsa), and gagye (pravarana)—and the daily schedule includes several sessions of meditation and recitation that everyone is required to attend. Included in the recitations are reminders of our responsibility to dedicate our lives and our practice to attaining enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, on whom we depend for all we have and use. To deepen the monastics’ knowledge of the Dharma, there are weekly classes in Vinaya as well as Lamrim, Bodhicaryavatara, philosophical subjects, and so forth.

The lay supporters who follow the Abbey’s online teaching program and/or come here for retreats are enormously appreciative of the monastics’ efforts to live in the precepts. They express this in their emails and letters, and through their wonderful acts of generosity—they provide all our daily needs such as food, and many of them volunteer their time and energy to help the Abbey with its projects. The success of the Abbey clearly illustrates the truth of Lord Buddha’s promise that anyone who keeps the precepts purely will never die of hunger or cold—even in America in the 21st century! And the sincere appreciation and support of the lay community inspires the monastics to do their best to repay their kindness by studying, practicing, and keeping their precepts.

My own experience of keeping the bhikshuni precepts is that they make me more mindful, mature, and serious about practicing Dharma. The teachings tell us that keeping precepts is highly meritorious; it’s one of the principal ways to create virtue and to purify nonvirtuous karma. And the more precepts we keep, the more we can accumulate merit and purify obscurations. That was my main reason for taking the ordination. I once heard Lama Zopa Rinpoche mention a quote from Lama Tsong Khapa saying that the best basis for practicing tantra was keeping the precepts of a fully-ordained monk. I thought, “If that is true for monks, it should also be true for nuns.”

Living in these precepts is also an important foundation for the bodhisattva vow, because it naturally makes you careful to act in beneficial and non-harmful ways, and to be more other-centered rather than self-centered. This is especially true of living in a monastery, where the harmony of the community depends on each person putting the needs of others/the community above their own personal needs and wishes.

This has been just a brief explanation of a vast and complicated subject. More information can be found on the website of The Committee for Bhikshuni Ordination in the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition: https://www.bhiksuniordination.org/index.html. This is a group of bhikshunis who were requested by the Dalai Lama in 2005 to do research on bhikshuni ordination. Two members of this group—Ven. Jampa Tsedroen and Ven. Thubten Chodron—were particularly helpful in checking and offering suggestions for this article. So I give my heartfelt thanks to them, and also I wish to express my deepest thanks to Shakyamuni Buddha, as well as to Mahaprajapti and all the bhikshunis in India, Sri Lanka, and China who have kept this ordination lineage alive to the present day, so that those who wish to live a full monastic life and engage in such powerful virtue can do so.

This paper can be downloaded at: http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-BJ001/93614.htm ↩

This account is according to the Pali Vinaya. According to the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, the 500 Shakyan women received ordination together with Mahaprajapati. ↩

There are also passages in the Vinaya texts saying that bhikshunis can be ordained by bhikshus alone—more will be said about this later. ↩

This figure is an estimate. As of now, no person or organization is keeping track of the number of bhikshunis in the world. ↩

This is the name of the Vinaya lineage followed in the Chinese and East Asian traditions, whereas the lineage followed in the Tibetan tradition is called Mulasarvastivada. ↩

See the full statement at: https://www.congress-on-buddhist-women.org/index.php-id=142.html ↩

One nun I know was asked this question by her teacher, a geshe, and she turned it around and asked him why he had wanted to become a gelong! ↩

The minimum age for taking full ordination is 20. ↩

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.16.1-6.vaji.html ↩

Dignity and Discipline, edited by Thea Mohn and Jampa Tsedroen, Wisdom Publications, p. 66. ↩

It seems that some texts say 365, but Je Tsongkhapa’s Essence of the Vinaya Ocean (‘Dul ba rgya mtsho’i snying po), which is recited during Sojong, says there are 364 bhikshuni vows: “Eight defeats, twenty suspensions, thirty-three lapses with forfeiture, a hundred and eighty simple lapses, eleven offences to be confessed, and the hundred and twelve misdeeds make three hundred and sixty-four things the bhikshuni abandons.” ↩

Choosing Simplicity by Ven. Bhikshuni Wu Yin (Snow Lion), p. 172. ↩

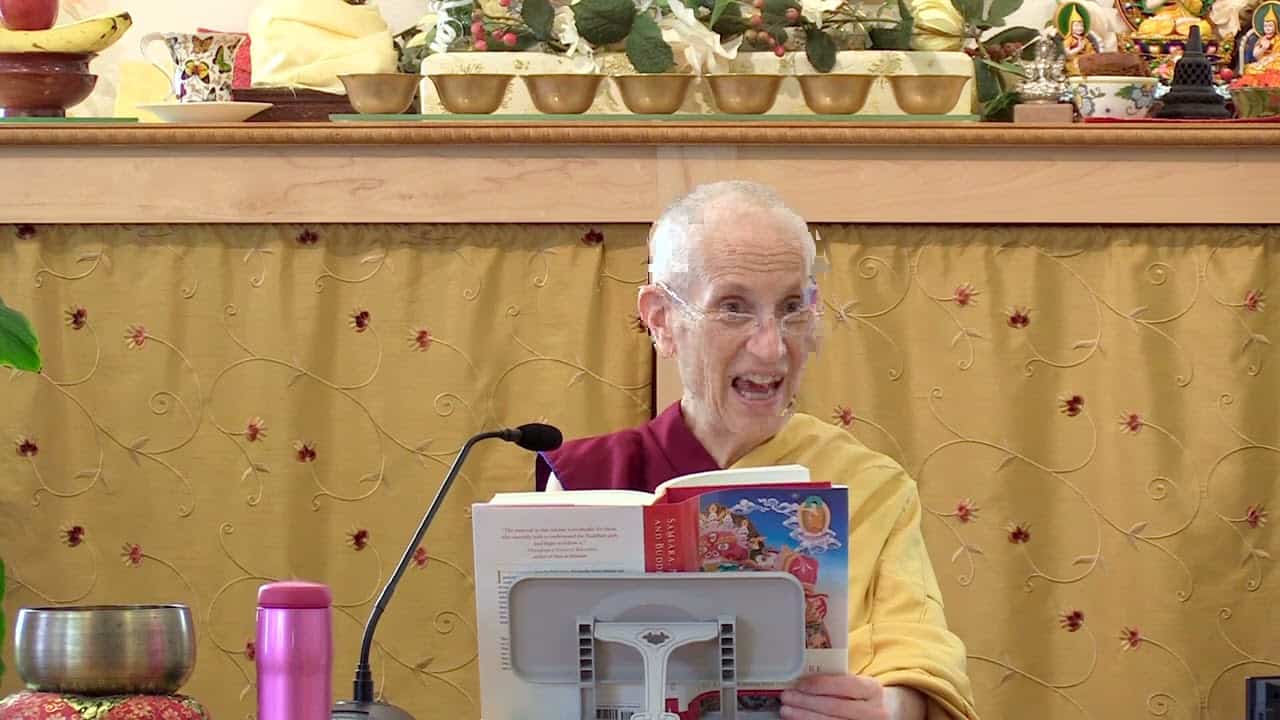

Venerable Sangye Khadro

California-born, Venerable Sangye Khadro ordained as a Buddhist nun at Kopan Monastery in 1974 and is a longtime friend and colleague of Abbey founder Venerable Thubten Chodron. She took bhikshuni (full) ordination in 1988. While studying at Nalanda Monastery in France in the 1980s, she helped to start the Dorje Pamo Nunnery, along with Venerable Chodron. Venerable Sangye Khadro has studied with many Buddhist masters including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, and Khensur Jampa Tegchok. At her teachers’ request, she began teaching in 1980 and has since taught in countries around the world, occasionally taking time off for personal retreats. She served as resident teacher in Buddha House, Australia, Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore, and the FPMT centre in Denmark. From 2008-2015, she followed the Masters Program at the Lama Tsong Khapa Institute in Italy. Venerable has authored a number books found here, including the best-selling How to Meditate. She has taught at Sravasti Abbey since 2017 and is now a full-time resident.