The call of monasticism

Princeton degree, dating brought no joy

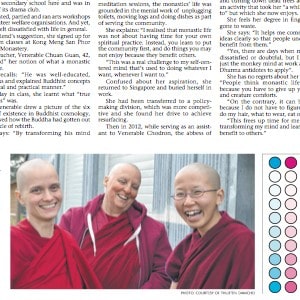

This article was originally published under the title, "The Call of Monkhood" in The Straits Times as part of a broader story on the experience of young Singaporean monastics.

Click here to download.

Growing up, Ms Ruby Pan wanted to be a writer. In her teens, she fell in love with the theater and dreamt of being a playwright.

She won a Public Service Commission teaching scholarship to study English literature at Princeton University in the United States, where she bagged prizes for a play and a collection of short stories she wrote.

She even got to perform a monologue she wrote at a show produced by the famous Royal Shakespeare Company in England.

She thought she had done everything that was artistically fulfilling, but when she graduated in 2006, she felt no joy.

She says: “Instead, I felt burnt out, like I had run a very long race for no reason.”

Ms Pan, 31, who now goes by her ordained name, Thubten Damcho, was speaking over the telephone from Sravasti Abbey, a Tibetan Buddhist monastry in a forested area in Washington in the United States, where she now lives.

In 2007, after returning to Singapore, she started teaching English language and literature at a secondary school here and was in charge of its drama club.

She dated, partied and ran arts workshops for volunteer welfare organisations. And yet, she still felt dissatisfied with life in general. At a friend’s suggestion, she signed up for Buddhism classes at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery.

The teacher, Venerable Chuan Guan, 42, “exploded” her notion of what a monastic should be.

She recalls: “He was well-educated, humorous and explained Buddhist concepts in a logical and practical manner.”

One day in class, she learnt what “true happiness” was.

The venerable drew a picture of the six realms of existence in Buddhist cosmology, and showed how the Buddha had gotten out of the cycle of rebirth.

She says: “By transforming his mind through moral conduct and meditation, he was no longer subject to an uncontrolled cycle of mental and physical suffering, and was able to benefit others.

“And I thought, ‘That’s what I want to do with my life! I wanted to follow in the Buddha’s footsteps.'”

For the next three years, she started to seriously consider being ordained as a nun. She attended a novice retreat, where she shaved her head and wore robes. She simplified her lifestyle and gave away things she did not need, including her books.

When she told her parents, both freethinkers, and sister, a Christian, about her intention, they were sad.

She says: “My mother cried and asked if she had done anything wrong. I told her, it’s because she has raised me well that I wanted to live a virtuous life.”

However, a two-week visit to Sravasti Abbey in 2010 to check out monastic life put her plans on hold.

She was shocked to find that in between meditation sessions, the monastics’ life was grounded in the menial work of unplugging toilets, moving logs and doing dishes as part of serving the community.

She explains: “I realised that monastic life was not about having time for your own spiritual practice. Instead, you learn to put the community first, and do things you may not enjoy because they benefit others.

“This was a real challenge to my self-centred mind that’s used to doing whatever I want, whenever I want to.”

Confused about her aspiration, she returned to Singapore and buried herself in work.

She had been transferred to a policy- making division, which was more competitive and she found her drive to achieve resurfacing. Then in 2012, while serving as an assistant to Venerable Chodron, the abbess of Sravasti Abbey, at a retreat in Indonesia, she saw again how her mind was overwhelmed with negativity.

For instance, she was jealous of her then boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend, whom she did not even know.

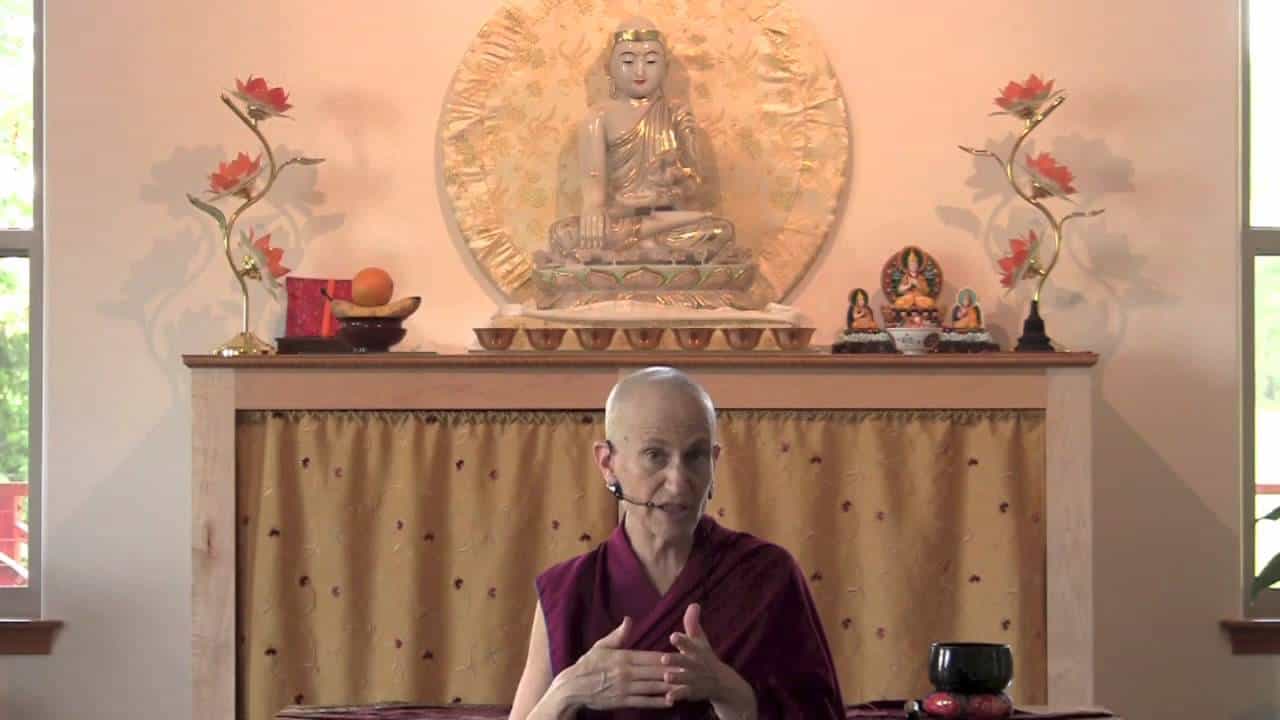

Conversely, she saw how the abbess was always joyous and equanimous regardless of the situation, the “fruit of decades of spiritual practice as a monastic.”

She quit her job two years ago and moved to the abbey in Washington, where, with her family’s blessings, she got ordained.

Her parents visited her once and she chats with them over Skype once every two weeks. Dad, 62, is a lecturer in mechanical engineering while mum, also 62, is a retired administrative executive. Her sister, 28, is a chemical engineer.

Among her main duties at the abbey are to edit and upload daily video teachings on YouTube.

She also spends a few afternoons in the forest every week doing fire prevention work and cutting down dead trees and branches, an activity that took her “a while to get used to” but which she now enjoys.

She feels her degree in English has not gone to waste.

She says: “It helps me communicate my ideas clearly so that people understand and benefit from them.”

“Yes, there are days when my mind gets dissatisfied or doubtful, but I know that’s just the monkey mind at work and there are Dharma antidotes to apply.”

She has no regrets about her chosen path: “People think monastic life is difficult because you have to give up your freedom and creature comforts.

“On the contrary, it can be liberating because I do not have to figure out how to do my hair, what to wear, eat or buy.

“This frees up time for me to focus on transforming my mind and learning to be of benefit to others.”