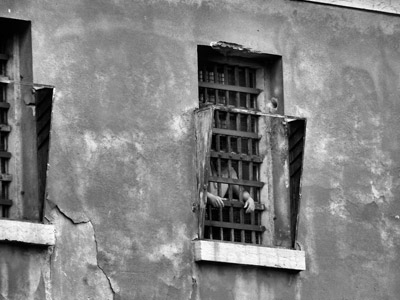

Prison outreach in Mexico

Individuals from the Rinchen Dorje Drakpa Buddhist Center in Xalapa, Mexico, had been doing prison outreach programs based on Buddhist principles but geared towards all incarcerated people, no matter their religious beliefs, in Vera Cruz State for a few years. The Department of Corrections administration noticed the effects of these programs and became interested in how to expand them and how to integrate their ideas into other prison programs. This talk was given to wardens and psychologists from the Department of Corrections in Vera Cruz State, Mexico.

I’m very happy to be here with you today and am honored and privileged to be able to share what little I know.

To begin our time together, let’s sit quietly for a few minutes and watch our breath. Sitting up straight with your eyes lowered, put your hands in your lap and then slowly become aware of your breath. Do not force your breath in or out, but let your breathing pattern be as it is. Simply observe and experience it. By focusing on one single object, in this case the breath, the mind gets quieter and clearer. However, if you get distracted by a thought or sound, simply notice it and then come back to the breath. In that way you stay in the present moment. Cultivate a sense of contentment: being content to sit here and breathe. We will take a few minutes of silence now for this meditation.

Before we actually begin let’s generate the motivation to listen and share together so that we may be of benefit to other living beings.

Let me start by telling you how I got involved with this prison program. I never intended to do prison work, but I’ve taken a vow to be of benefit to those who ask for help. In 1996 or 1997, I received a letter from an incarcerated person asking for help with his meditation practice. I have no idea how he got my address, but I responded in writing and some time later was able to visit him in prison. During that visit, I also talked with the Buddhist group in the prison. Meanwhile this person told some of his friends in other prisons and they also started to write to me. One thing led to another and now we have an active prison program at the monastery where I live.

This prison program has many components, and people across the country have volunteered to help. Many incarcerated people write to us, sharing the experiences of their lives, and we correspond with as many of them as we can. We also send them Buddhist books free of charge and donate books to the chapel library in the prisons. Recently, we received a grant from the Rotary Club in Spokane to support the production of a set of DVDs with 28 talks that I gave on mind training, or how to transform adversity into the path.

We also publish a newsletter, which includes articles written by incarcerated people as well as Buddhist teachings, and it is sent to all those who contact us. On the thubtenchodron.org website, we have created a section that includes the writings and art work of incarcerated people.

Several of us from the Abbey go to different prisons around the US to visit incarcerated people who have been writing to us. If the prison has a Buddhist or meditation group, we give talks and teach meditation in those groups. If the prison does not have a regular group, the prison staff will arrange for us to give a talk for those who want to attend. The topic might be “Dealing with Stress” or “Working with Anger.” (One of my students has developed a program called “Working With Anger” that is completely secular but based on Buddhist techniques. He also wrote a guide for people who are guiding the program on how to do it.)

Each year at Sravasti Abbey, we do a three-month meditation retreat in the winter, and we invite incarcerated people to do one session daily of the retreat with us. We ask them to send us a picture, which we put it in the meditation hall alongside pictures of other people who are participating in the “retreat from afar.” We regularly send them transcripts of the talks and teachings during the retreat. There were over 80 incarcerated people who participated in the retreat this year. They tell us how helpful it is to feel part of a community meditating together and how much they benefit from having a consistent meditation practice.

There are a number of Buddhist groups doing prison work in the US. The Prison Dharma Network was founded by Fleet Maull, who spent 14 years in federal prison for drug trafficking. Another group is called the Liberation Prison Project that does similar work in prisons.

There are some basic principles in this work which we find resonate with people in prison. It is important to clarify here that we are not trying to convert anybody. Because some people consider Buddhism a religion and others consider it a psychology, we approach this work in a very secular way. So much of Buddhist meditation and psychology applies to everybody regardless of their religious beliefs. Our motivation is to share what we know so that others can benefit from it.

Our practice begins with meditation. The Tibetan word for meditation comes from the same root that means to familiarize or habituate. We are trying to familiarize ourselves with useful and constructive ways of thinking and feeling. We seek to bring our minds out of ruminating on the past and future with fear, anxiety, or attachment and to put our attention on a virtuous object in this present moment. We are also trying to familiarize ourselves with a sense of calm and peace in our own hearts.

For most of us, our thoughts run wild. Do you also have that experience when you are watching the breath? Can you concentrate just on the breath without having any other thoughts? It’s difficult isn’t it? It is especially difficult to train the mind to keep the focus on the breath that is happening right now in the present moment. Usually our minds are in the past or in the future. We have memories of the past, we get angry at what people did to us, we feel regret about what happened, or we feel desire to recreate what happened in the past. We look at the future and become worried and anxious, fearful about what is going to happen next, especially with the economy, our job, and our relationships. We get stuck creating stories in our mind; these stories then create emotions, and we get completely absorbed in things that are not happening now. We are very seldom actually in this moment.

However, we cannot live in the past and we cannot live in the future. The only time we actually live is in this moment. The process of bringing the mind continually back to the present, especially through watching the breath, helps us realize that all of our thoughts and emotions about the past and future are simply that—just thoughts. Those things are not happening now. As we maintain a meditation practice, we begin to see much more clearly how our minds work. As we do this practice and develop the ability to focus on what is important, our minds really do settle down.

When we visit the prison, we will often do breathing meditation or another meditation practice. Through this, all of us see that we are with a room full of kind, like-minded people. But we also notice that sometimes we will remember something that happened in the past. The mind starts to ruminate about it and get angry, upset and really distressed about it. Then we hear this little bell ding at the end of the meditation session and open our eyes only to realize that the whole scene we were getting so upset about was only going on our mind. It’s not out here at all.

As we apply the teachings, we begin to notice and it is pointed out to us that all these stories we make up about the past are things we invent and create in our own minds. They are all based on the thought “I am the center of the universe,” because all these things about the past that run through the mind are all about ME. We think about what people did to me, how unfair it was to me, all the suffering I went through. At some point, though, the absurdity becomes very clear—there is a planet with nearly seven billion human beings on it and the one I think about almost all the time is myself. We then begin to question if this is really an accurate view of the universe; are we really the center of the universe as our self-centered mind believes? Is everything that happens to us the most important thing on the entire planet? As we begin to look at this and understand it, we see the disadvantages of that self-centered thought. We see how, motivated by this self-centered thought, we become attached to things. Then we steal, lie, cheat, and do all sorts of nasty things to people to get what we want. We get upset when people do things that interfere with our happiness, and then we fight with them verbally or physically to stop them.

Eventually, we begin see how we ourselves create the situations we are in. For incarcerated people, they begin to see how they got themselves in prison. This is a big shift, because usually people in prison tend to blame others for their circumstances. They usually come to prison extremely angry. They are mad at the other people involved in the crime they committed, they are mad at people who testified against them, they are mad at the police, and they are mad at the prison system. When they are angry, they cannot take responsibility for their own lives because they are too busy blaming others for their problems. As they begin to see that their own self-centered thoughts motivated them to act in ways that resulted in their doing time, they cannot continue the anger and the blame.

One of the incarcerated people I work with wrote me a beautiful letter about causes and consequences. He had a 20-year federal sentence because he was a big drug dealer in the L.A. area. When his bubble burst and he was brought in to serve his 20 years, he went into shock. In his meditation practice he just started looking at the present moment, asking, “How did I get here? How did my life turn out this way?” Then he started looking back, and began to see that even at an early age small decisions set him on different tracks that led to other decisions and situations that finally led to him to prison. He said that even very small inconsequential decisions which were made without much thought actually had very powerful long-term results. This woke him up, because he saw how he created this situation and realized that if he wants his life to be different, he has to start making different decisions now. He also recognized that these decision cannot be continually be based on “me, I, my and mine,” what I what, and what I like.

One very important point in working with incarcerated people is that I don’t separate myself out from them. I don’t look at them as full of anger and greed and see myself as without those qualities. When I look at my own mind, I see that my mind does the same thing as their mind does. I talk about “us” and how “our” minds work, putting myself right in there with them. This is very important because as soon as we make a separation between “us and them,” thinking that we have it all together and they do not, they stop listening to us. When we are arrogant, when we separate ourselves out from them, they notice it right away and dismiss us.

Another principle that we introduce in working with incarcerated people is what we call Buddha potential or, to put it in secular language, inner goodness. In other words, the basic nature of our hearts or minds is something pure. We are not inherently selfish. We may have made mistakes in our lives but we are not inherently bad people. We may have a lot of attachments and a lot of greed but these are not inherent qualities in us. We may have an outrageous temper, but it is not who we really are. In other words, we don’t have fixed personalities. These faults are not the true nature of our minds. There exist antidotes which make it possible to eliminate these undesirable qualities. Our basic nature is like the open sky while ignorance, anger, attachment, arrogance, and jealousy are like clouds in the sky. It is possible to remove the clouds and see the sky’s clear nature. It is possible to eliminate the afflictive emotions and see our own inner goodness. This gives all of us—and especially those incarcerated—a sense of hope in our lives and a sense of self-confidence.

Most people in prison lack a valid sense of self-confidence. When they feel that they are worth nothing and their lives are a mess, then that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. On the other hand, when they see that they are not identical to their afflictive emotions—that these emotions are transient, conditioned, and based on incorrect ways of viewing things—they realize it is actually possible to purify and let go of these afflictions. “These afflictions are not me. They are not who I am. They are not the sum total of my life.” Thinking like this gives them faith that they can change and become the kind of person that they really want to be in the depths of their hearts. Once they have a feeling that there is a basic inner goodness inside and they are not identical to their afflictions, they gain a sense of self-confidence and purpose in their lives that can really change things.

Related to this notion of inner goodness or Buddha nature is the potential for love and compassion. In other words, we all have the seeds of far-reaching love and compassion in us right now. We can water these seeds so that they will grow and we will become more compassionate. We talk to incarcerated people about cultivating the motivation to fulfill our highest spiritual potential because we want to be of the greatest benefit to others. Suddenly they “get it” and are very excited by the idea of their lives becoming useful for others. It gives them a vision of what they can become and of how they can contribute to the welfare of others. This also increases their sense of self-confidence, which is so important.

We also encourage people to learn to laugh at themselves. Humor is quite helpful as we work to transform our thoughts and attitudes, and I have found it very useful in presenting these teachings on transforming our mind in this way. We need to learn to laugh at ourselves. It’s healthy psychologically when we can look back at some of the silly things that we have thought and stupid things we have done, and laugh instead of feeling so guilty or downtrodden. This helps us move forward in a constructive manner.

We also teach a kind of meditation that is called purification. As we begin to meditate and look inside of ourselves, we see that we have not always been little angels but have done harmful things. A wish arises in our mind to purify any remaining negative energy that is a result of these harmful actions. Here we teach incarcerated people another kind of mediation, one that involves visualization. We imagine, for example, a ball of light in front of us that is the essence of all the good qualities that we want to become. This might include self-acceptance, forgiveness for ourselves and others, and compassion for oneself as well as for others. Then in our meditation we identify and acknowledge our misdeeds and have a deep sense of regret for them. Next, we imagine that light radiates from this ball of light, absorbing into us and filling our body-mind so that all the energy from the misdeeds is completely purified. If there is a troubling situation from the past, we envision the other people in that situation around us and the light filling them up, purifying their hearts and minds and soothing any ill feelings. We may also imagine ourselves surrounded by all living beings, thinking that this blissful, purifying light fills all of us, leaving us peaceful and serene, free from guilty, blame, and resentment. To conclude the meditation, we imagine the ball of light dissolves into us and we think we become the nature of all the good qualities that we want to cultivate.

A third type of meditation we use is called checking or analytical meditation. Here we actually think about a particular topic. For example, there are many different techniques to use to combat anger. There are different ways of looking at a situation so that we describe it to ourselves in a different way. In training the mind to see the situation differently, we find there is no reason to be so get angry. For example, if we see that the other person was anxious and scared, we stop attributing to them the wish to harm us and instead see that they were suffering and did what they did in an attempt to be happy. However, since they were confused, they did something harmful instead. We think, “I, too, have been upset or angry an done useless or even harmful things in an attempt to be happy. I know what that’s like.” That gives space in our minds to have compassion for ourselves and for the other person. When compassion is in our mind, there is no place for anger.

This type of meditation has many points in common with psychotherapy and with Alcoholics Anonymous. Reflecting on our lives and actions, relying a higher power—the Buddha or whomever or whatever accords with one’s spiritual beliefs—purifying our misdeeds, and deciding to change; all this is similar to the 12 steps.

A few years ago, when I came for my annual teaching visit to Xalapa, the Buddhist group here organized some prison visits and several members of the group went with me. They saw the benefit and decided to do prison outreach themselves. We discussed what they could do and now six to eight people from the Xalapa Dharma center have been running a program entitled “Emotional Health” in several prisons. It is open to people from any religion and people who do not follow a particular religion. While it is based on Buddhist concepts and methods, the program is nonreligious in nature. They have translated some materials from English and also developed their own materials that are more suitable for Mexican culture. Their programs have been very successful, with some prison staff attending in addition to incarcerated people.

This has been a brief overview of our prison work. We have time for some questions and discussion. Don’t be shy because chances are there are a few other people who have the same question you do.

Audience: How can we have access to your work so that we can start experimenting with this?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): There’s a Buddhist center here in Xalapa, Centro Budista Rechung Dorje Dragpa. You can go there and start learning some of these techniques. It is essential to do them yourself before teaching them to others. You may want to form a group of people, especially people who work in prisons, and ask people from the Buddhist center to instruct you. Also, visit my website thubtenchodron.org, where you’ll find the teachings and guided meditations in audio, video, and written forms. There is quite extensive material.

Audience: What are different types of meditation?

VTC: One is called stabilizing meditation, and its purpose is to help us calm the mind and to increase concentration. Another meditation is called analytical or checking meditation where we think about some of the teachings but in a very personal way, applying them to our own lives. This trains us learn to look at things in life from a different perspective which thus changes our emotional reaction to them. We also do a number of visualization practices, which are very helpful for integrating some of the things we learn but in a more symbolic way. Sometimes we recite mantras as well to help focus and purify the mind. Using all these different types of meditation is helpful.

Audience: Can this work can only be done with incarcerated people that are mentally healthy or we can do it with others?

VTC: They work better with those who are not psychotic or schizophrenic.

Thank you very much for letting me share with you. I really appreciate all the work you are doing on behalf of incarcerated people. It is such an incredible opportunity to make our lives meaningful and useful by helping others. One of the things I have noticed from working with people in prison is that I actually learn more from them than I teach. So I’m very grateful to them for what they share with me.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.