Bhikkhuni education today

Seeing challenges as opportunities

A paper presented at the 2009 International Conference for Buddhist Sangha Education held in Taipei, Taiwan.

From its origins, Buddhism has been intimately involved with education. Education plays such an important role in Buddhism because the Buddha teaches that the root cause of suffering is ignorance, a deluded understanding of the nature of things. For Buddhism, one walks the path to liberation by cultivating wisdom, and this is acquired through a systematic program of education. The Buddha’s communication of his message to the world is a process of instruction and edification. We often read in the suttas that when the Buddha gives a discourse, “he instructs, encourages, inspires, and gladdens” the assembly with a talk on the Dharma. The Buddha’s teaching is known as Buddha-Vacana, the “Word of the Buddha.” Words are meant to be heard. In the case of the Buddha’s words, which reveal liberating truth, they are meant to be listened to attentively, reflected upon, and deeply understood.

According to the vinaya, newly ordained monks and nuns are obliged to spend several years living under the guidance of their teacher, during which they learn the fundamentals of the Buddha’s teaching. The Buddha’s discourses often describe five distinct stages in the progress of education:

A monk is one who has learned much, who retains in mind what he has learned, repeats it, examines it intellectually, and penetrates it deeply with insight.

The first three stages are concerned with learning. In the Buddha’s days, there were no books, so to learn the Dharma one had to approach erudite teachers in person, listening closely to what they taught. Then one had to retain it in mind, to remember it, to impress it deeply on the mind. To keep the teaching fresh in the mind, one had to repeat it, review it, by reciting it out loud. At the fourth stage one examines the meaning. And at the fifth, which culminates the process, one penetrates it with insight, one sees the truth for oneself.

The aims of classical Buddhist education

Wherever Buddhism took root and flourished, it has always emphasized the importance of study and learning. In India, during the golden age of Buddhist history, Buddhist monasteries evolved into major universities which attracted students throughout Asia. As Buddhism spread to different Asian countries, its monasteries became centers of learning and high culture. The village temple was the place where youngsters would learn reading and writing. The great monasteries developed rigorous programs of Buddhist studies where Buddhist scriptures and philosophies were investigated, discussed, and debated. Yet always, in the long history of Buddhism, the study of the Dharma was governed by the aims of the Dharma. The teachers of Buddhism were mostly monastics, the students were mostly monastics, and learning was pursued out of faith and devotion to the Dharma.

And what were the aims of classical Buddhist education?

- The first was simply to know and understand the texts. Buddhism is a religion of books, many books: scriptures passed down directly from the mouth of the Buddha or his great disciples; sayings of enlightened sages, arahants, and bodhisattvas; treatises by Buddhist philosophers; commentaries and sub-commentaries and sub-sub-commentaries. Each Buddhist tradition has given birth to a whole library filled with books. Thus a primary aim of traditional Buddhist education is to learn these texts, and to use them as a lens for understanding the meaning of the Buddha’s teaching.

- One learns the texts as part of a process of self-cultivation. Thus a second aim of Buddhist education is to transform ourselves. Knowledge, in classical Buddhism, is quite different from the kind of factual knowledge acquired by a scientist or scholar. The secular scholar aims at objective knowledge, which does not depend on his character. A scientist or secular scholar can be dishonest, selfish, and envious but still make a brilliant contribution to his field. However, in Buddhism, knowledge is intended to mold our character. We learn the Dharma so that we can become a better person, one of virtuous conduct and upright character, a person of moral integrity. Thus we use the principles that we learn to transform ourselves; we seek to make ourselves suitable “vessels” for the teaching. This means that we have to govern our conduct in accordance with precepts and discipline. We have to train our hearts to overcome the mental afflictions. We have to mold our character, to become kind, honest, truthful, and compassionate human beings. The study of the Dharma gives us the guidelines we need to achieve this self-transformation.

- On this basis we turn to the teachings concerned with personal insight and wisdom. This brings us to the third aim of classical Buddhist education: to develop wisdom, an understanding of the real nature of things, those principles that remain ever true, always valid. Whether a Buddha appears in the world or does not appear; whether a Buddha teaches or does not teach, the Dharma always remains the same. A Buddha is one who discovers the Dharma, the true principles of reality, and proclaims them to the world. We ourselves have to walk the path and personally realize the truth. The truth is simply the nature of phenomena, the true nature of life, which is hidden from us by our distorted views and false concepts. By straightening out our views, correcting our concepts, and cultivating our minds, we can attain realization of the truth.

- Finally, we use our knowledge of the Dharma—gained by study, practice, and realization—to teach others. As monastics, it is our responsibility to guide others in walking the path to happiness and peace, to instruct them in ways that will promote their own moral purification and insight. We study the Dharma to benefit the world as much as to benefit ourselves.

The challenge of academic learning

As we enter the modern era, the traditional model of Buddhist education has met a profound challenge coming from the Western academic model of learning. Western education does not seek to promote spiritual goals. One does not enroll in an academic program of Buddhist studies at a Western university in order to advance along the path to liberation. The aim of academic Buddhist studies is to transmit and acquire objective knowledge about Buddhism, to understand Buddhism in its cultural, literary, and historical settings. Academic Buddhist studies turns Buddhism into an object detached from the inner spiritual life of the student, and this constitutes a departure from the traditional model of Buddhist learning.

The academic approach to Buddhist studies poses a challenge to traditional Buddhism, but it is a challenge we should accept and meet. There are two unwise attitudes we can take to this challenge. One is to turn away and reject the academic study of Buddhism, insisting exclusively upon a traditionalist approach to Buddhist education. A traditionalist education might make us learned monks and nuns who can function effectively in a traditional Buddhist culture; however, we live in the modern world and must communicate with people who have received a modern education and think in modern ways. By taking a strictly traditionalist approach we may find ourselves like dinosaurs with shaved heads and saffron robes. We would be like the Christian fundamentalists who reject modern sciences—such as geology and evolution—because they contradict a literal interpretation of the Bible. This would not be helpful to promote acceptance of the Dharma.

The other unwise attitude would be to reject the traditional aims of Buddhist education and follow the academic model in making objective knowledge about Buddhism the whole purpose of our educational policy. This would mean that we abandon the religious commitments we make when we take vows as monks and nuns. Adopting this approach could turn us into learned scholars, but it might also turn us into skeptics who regard Buddhism as just a ladder for advancing in our academic careers.

Adopting a middle way

What we need to do is to adopt a “middle way” that can unite the best features of traditional Buddhist education with the positive values of a modern academic approach to Buddhist studies. And what are these positive values of traditional Buddhist education? I already dealt with this when I discussed the aims of traditional Buddhist education. In brief, the traditional approach to education is geared to enable us to cultivate our character and conduct, to develop wisdom and deep understanding of the Dharma, and to assist in guiding others, thereby contributing to the transmission of Buddhism from one generation to the next.

What are the positive values of the modern academic approach? Here, I will mention four.

- Academic study of Buddhism helps us understand Buddhism as a historical and cultural phenomenon. Through the study of Buddhist history, we see how Buddhism arose against a particular historical background; how it responded to cultural and social forces in India during the Buddha’s time; how it evolved through intellectual exploration and in response to changing historical conditions. We also see how, as Buddhism spread to different countries, it had to adapt to the prevailing social norms, cultures, and worldview of the lands in which it took root.

- This historical overview helps us to comprehend more clearly the distinction between the essence of the Dharma and the cultural and historical “clothing” that Buddhism had to wear to blend in with its environment. Just as a person might change clothes according to the season while remaining the same person, so as Buddhism spread from country to country, it retained certain features distinctive of Buddhism while adjusting its outer forms to conform to the prevailing cultures. Thus, through the study of Buddhist history and the different schools of Buddhist philosophy, we can better grasp the core of the Dharma, what is central and what is peripheral. We will understand the reasons why Buddhist doctrines took the forms they did under particular conditions; we will be able to discriminate which aspects of Buddhism were adapted to particular situations and which reflect the ultimate, unchanging truth of the Dharma.

- The academic study of Buddhism sharpens our capacity for critical thinking. What is distinctive about all modern academic disciplines is the premise that nothing should be taken for granted; all assumptions are open to questioning, every field of knowledge should be examined closely and rigorously. Traditional Buddhist education often emphasizes unquestioning acceptance of texts and traditions. Modern academic education invites us to argue with every Buddhist belief, every text, every tradition, even those supposed to come from the Buddha himself. While such an approach can lead to fruitless skepticism, if we remain firm in our dedication to the Dharma, the discipline of modern education will strengthen our intelligence, like a steel knife tempered in a fire. Our faith will emerge stronger, our intellect will become keener, our wisdom will be brighter and more potent. We will also be better equipped to adapt the Dharma to the needs of the present age without compromising its essence.

- The academic study of Buddhism also fosters creative thinking. It does not merely impart objective information, and it often does not stop with critical analysis. It goes further and encourages us to develop creative, original insights into different aspects of Buddhist history, doctrine, and culture. Academic study of Buddhism aims to enable us to arrive at new insights into causal factors that underlie the historical evolution of Buddhism, to discern previously undetected relationships between the doctrines held by the different Buddhist schools, to discover new implications of Buddhist thought and new applications of Buddhist principles to the resolution of problems in such contemporary fields as philosophy, psychology, comparative religion, social policy, and ethics.

The interplay of critical thought and creative insight is actually how Buddhism itself has evolved through the long course of its history. Each new school of Buddhism would begin with the criticism of some earlier stage of Buddhist thought, uncover its inherent problems, and then offer new insights as a way of resolving those problems. Thus, the academic study of Buddhism can contribute to the same process of creative growth, innovation, exploration, and development that has resulted in the great diversity of Buddhism in all its geographical and historical extensions.

Buddhist education and the encounter of traditions

This brings me to the next point. Ever since Buddhism left India, different Buddhist traditions have flourished in different geographical regions of the Buddhist world. Early Buddhism, represented by the Theravāda school, has flourished in southern Asia. Early and middle-period Mahāyāna Buddhism spread to East Asia, giving birth to new schools like Tiantai and Huayan, Chan and Pure Land, that suit the East Asian mind. And late-period Mahāyāna Buddhism and Vajrayāna spread to Tibet and other Himalayan lands. For centuries, each tradition has remained sealed off from the others, a world in itself.

Today, however, modern methods of communication, transportation, and book production give scholars from each tradition the opportunity to study all the major Buddhist traditions. Of course, each tradition is a lifetime of study in itself, but with the growing connections between people in different Buddhist lands, any program in monastic education should expose students to teachings from the other traditions. This will give students a greater appreciation of the diversity of Buddhism, its transformations throughout history; its rich heritage of philosophy, literature, and art; and its ability to profoundly influence people in different cultures as determined by their own points of emphasis. Perhaps a complete program of monastic education would give monks and nuns the chance to spend a year in a monastery or university in another Buddhist country, just as university students often spend their junior year abroad. Learning and practicing a different Buddhist tradition will help to widen their minds, allowing them to understand the diverse range of Buddhism as well as its common core.

It is possible that such encounters will transform the face of Buddhism itself in the contemporary world. It may lead to cross-fertilization and even hybrid formation, whereby new forms of Buddhism emerge from the synthesis of different schools. At the minimum, it will serve as a catalyst encouraging more attention to be given to aspects of one’s own tradition that have generally been under-emphasized. For example, the encounter with southern Theravāda Buddhism has stimulated interest in the Agamas and Abhidharma in East Asian Buddhism. When Theravāda Buddhists study Mahāyāna Buddhism, this can stimulate an appreciation of the bodhisattva ideal in the Theravāda tradition.

Engaging with the modern world

We Buddhist monastics do not live in a vacuum. We are part of the modern world, and an essential part of our monastic education should teach us how to relate to the world. From its origins, Buddhism has always engaged with the cultures in which it found itself, attempting to transform society in the light of the Dharma. Because monasteries are often situated in quiet places removed from the bustle of normal life, we sometimes imagine that Buddhism teaches us to turn our backs on society, but this would be a misunderstanding. As monastics, we should not lose sight of our obligations to people living in the world.

Today our responsibility has become more urgent than ever before. As humanity has learned to master the material forces of nature, our capacity for self-destruction has increased by leaps and bounds. The discovery of nuclear power has enabled us to create weapons that can obliterate the entire human race at the press of a button, but the threat of human self-annihilation is still more subtle. The world has become more sharply polarized into the wealthy and the poor, with the poor populations sliding into deeper poverty; in many countries, the rich get richer and the poor become poorer. Billions live below the poverty line, subsisting on one or two meager meals a day. Poverty breeds resentment, increasing communal tensions and ethnic wars. In the industrialized world, we recklessly burn up our natural resources, polluting the environment, burdening the air with more carbon than it can hold. As the earth’s climate grows warmer, we risk destroying the natural support systems on which human survival depends.

As Buddhists, we have to understand the forces at work in today’s world, and to see how the Dharma can preserve us from self-destruction. We need programs of study, even for monastics, that go beyond a narrow fixation on Buddhist studies and prepare Buddhist monks and nuns to deal with these global problems. The core of Buddhist education should, of course, emphasize learning classical Buddhist traditions. But this core education should be supplemented by courses that cover other areas where Buddhism can make a substantial contribution to improving the condition of the world. These would include such subjects as world history, modern psychology, sociology, bio-ethics, conflict resolution, and ecology, perhaps even economics and political science.

In today’s world, as Buddhist monks and nuns, we have an obligation to raise high the torch of the Dharma, so that it can shed light on the suffering people living in darkness. To be effective in this role, Buddhist education must equip us to understand the world. This expansion of Buddhist education may draw objections from strict traditionalists, who think that monastics should confine themselves to Buddhist studies. They might point out that the Buddhist scriptures prohibit monks even from discussing such topics as “kings, ministers, and affairs of state.” But we have to realize that today we live in a very different era from that into which the Buddha was born. Buddhism flourishes to the extent it maintains its relevance to human affairs, and for it to maintain its relevance we must understand the enormous problems that confront humankind today and see how we can use the Dharma to find solutions to them. This will require a rigorous and radical revision of traditional programs of Buddhist studies, but such renovation is essential for Buddhism to discover its contemporary relevance.

The challenge and opportunity for bhikkhunis

One aspect of our contemporary situation deserves special mention at a conference about the education of Buddhist nuns, and that is the role of women in today’s world. As you all know, most traditional cultures, including those where Buddhism has thrived, have been predominantly patriarchal. Even though the Buddha himself promoted the status of women, still, he lived and taught during the Patriarchal Age and thus his teachings inevitably had to conform to the dominant outlook of that era. This has been the case up to the modern age.

Now, however, in our present-day world, women are breaking free from the constraints of a male-dominated worldview. They have claimed the same rights as men and are taking more active roles in almost every sphere of human life, from professions like law and medicine, to university positions, to national leadership as presidents and prime ministers. There is no doubt that this “rediscovery of the feminine” will have a transformative effect on Buddhism as well. Already, some women have become prominent scholars, teachers, and leaders in Buddhism. Several traditions that lost the bhikkhuni ordination have recovered it, and hopefully, in the near future, all forms of Buddhism will have thriving communities of fully ordained bhikkhunis.

The time has come for women to emerge from their secondary roles in the living tradition of Buddhism and to stand alongside men as teachers, interpreters, scholars, and activists. This applies to nuns as well as to laywomen, probably even more so. But the key to the advancement of women, in monastic life as in lay life, is education. It is therefore necessary for bhikkhunis to achieve a level of education equal to that of their bhikkhu-brothers in the Sangha. They should attain competency in every sphere of Buddhist education—in Buddhist philosophy, culture, and history, as well as in the application of Buddhism to the problems of modern society. I sincerely hope that this conference, which brings together Buddhist nuns and educators from many traditions, will contribute to this aim.

I thank you all for your attention. May the blessings of the Triple Gem be with you all.

Bhikkhu Bodhi

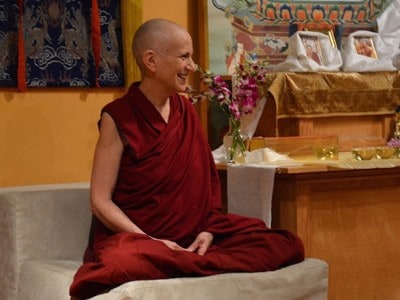

Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, ordained in Sri Lanka and currently teaching in the New York/New Jersey area. He was appointed the second president of the Buddhist Publication Society and has edited and authored several publications grounded in the Theravada Buddhist tradition. (Photo and bio by Wikipedia)