The challenge of the future

The challenge of the future, Page 2

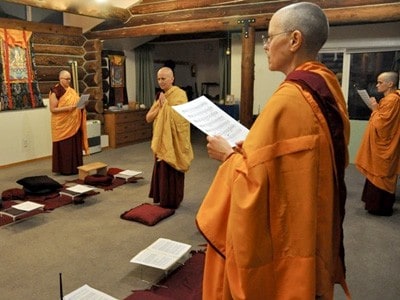

How will the sangha fare in North American Buddhism?

At this point I want to consider some of the peculiar challenges that Buddhist monasticism is facing today, in our contemporary world, especially those that arise out of the unique intellectual, cultural, and social landscape of modern Western culture. Such challenges, I have to emphasize, are already at work; they have brought about remarkable changes in the contemporary manifestation of Buddhism as a whole. It is likely, too, that they will accelerate in the future and have a significant impact on Buddhist monasticism over the next few decades.

I believe the present era confronts us with far different challenges than any Buddhism has ever faced before. These challenges are more radical, more profound, and more difficult to address using traditional modes of understanding. Yet for Buddhist monasticism to survive and thrive, they demand fitting responses—responses, I believe, that do not merely echo positions coming down from the past, but tackle the new challenges on their own terms while remaining faithful to the spirit of the teaching. In particular, we have to deal with them in ways that are meaningful against the background of our own epoch and our own culture, offering creative, perceptive, innovative solutions to the problems they pose.

On what grounds do I say that the present era confronts Buddhist monasticism with far different challenges than any it has faced in the past? I believe there are two broad reasons why our present-day situation is so different from anything Buddhist monasticism has encountered in the past. The first is simply that Buddhist monasticism has taken root in North America, and most of us involved in the project of establishing Buddhist monasticism here are Westerners. When, as Westerners, we take up Buddhism as our spiritual path, we inevitably bring along the deep background of our Western cultural and intellectual conditioning. I don’t think we can reject this background or put it in brackets, nor do I think doing so would be a healthy approach. We cannot alienate ourselves from our Western heritage, for that heritage is what we are and thus determines how we assimilate Buddhism, just as much as a brain that processes objects in terms of three dimensions determines the way we see them.

The second reason is partly related to the first, namely, that we are living not in fifth century B.C. India, or in Tang dynasty China, or in fourteenth century Japan or Tibet, but in 21st century America, and thus we are denizens of the modern age, perhaps the postmodern age. As people of the 21st century, whether we are indigenous Americans or Asians, we are heirs to the entire experience of modernity, and as such we inevitably approach the Dharma, understand it, practice it, and embody it in the light of the intellectual and cultural achievements of the modern era. In particular, we inherit not only the heritage of enlightenment stemming from the Buddha and the wisdom of the Buddhist tradition, but also another heritage deriving from the 18th century European Enlightenment. The 18th century cut a sharp dividing line between traditional culture and modernity, a dividing line that cannot be erased; it marked a turning point that cannot be reversed.

The transformations in thought ushered in by the great thinkers of the Western Enlightenment— including the Founding Fathers of the U.S.—dramatically revolutionized our understanding of what it means to be a human being existing in a world community. The concept of universal human rights, of the inherent dignity of humankind; the ideals of liberty and equality, of the brotherhood of man; the demand for equal justice under the law and comprehensive economic security; the rejection of external authorities and trust in the capacity of human reason to arrive at truth; the critical attitude towards dogmatism, the stress on direct experience—all derive from this period and all influence the way we appropriate Buddhism. I have seen some Western Buddhists take a dismissive attitude towards this heritage (and I include with them myself during my first years as a monk), devaluing it against the standards of traditional pre-modern Asian Buddhism. But in my opinion, such an attitude could become psychologically divisive, alienating us from what is of most value in our own heritage. I believe a more wholesome approach would aim at a “fusion of horizons,” a merging of our Western, modernist modes of understanding with the wisdom of the Buddhist tradition.

I would now like to briefly sketch several intellectual and cultural issues with which Buddhism has to grapple here in the U.S. I won’t presume to lay down in categorical terms fixed ways that we should respond to this situation; for the plain fact is that I don’t have definitive solutions to these problems. I believe the problems have to be faced and discussed honestly, but I don’t pretend to be one who has the answers. In the end, the shape Buddhist monasticism takes might not be determined so much by decisions we make through discussion and deliberation as by a gradual process of experimentation, by trial and error. In fact, it seems to me unlikely that there will be any simple uniform solutions. Rather, I foresee a wide spectrum of responses, leading to an increasing diversification in modern American/Western Buddhism, including monasticism. I don’t see this diversity as problematic. But I also believe it is helpful to bring the challenges we face out into the light, so that we can exlpore them in detail and weigh different solutions.

I will briefly sketch four major challenges that we, as Buddhist monastics, face in shaping the development of Buddhism in this country.

1. “The leveling of distinctions”: One important contemporary premise rooted in our democratic heritage might be called “the leveling of distinctions.” This holds that in all matters relating to fundamental rights, everyone has an equal claim: everyone is entitled to participate in any worthy projects; all opinions are worthy of consideration; no one has an intrinsic claim to privilege and entitlement. This attitude is staunchly opposed to the governing principle of traditionalist culture, namely, that there are natural gradations among people based on family background, social class, wealth, race, education, and so on, which confer privileges on some that do not accrue to others. In the traditionalist understanding, monastics and laity are stratified as to their positions and duties. Lay people provide monks and nuns with their material requisites, undertake precepts, engage in devotional practices to acquire merit, and occasionally practice meditation, usually under the guidance of monks; monastic persons practice intensive meditation, study the texts, conduct blessing ceremonies, and provide the lay community with teachings and examples of a dedicated life. This stratification of the Buddhist community is typical of most traditional Buddhist cultures. The distinction presupposes that the Buddhist lay devotee is not yet ready for deep Dharma study and intensive meditation practice but still needs gradual maturation based on faith, devotion, and good deeds.

In modern Western Buddhism, such a dichotomy has hardly even been challenged; rather, it has simply been disregarded. There are two ways that the classical monastic-lay distinction has been quietly overturned. First, lay people are not prepared to accept the traditionalist understanding of a lay person’s limitations but seek access to the Dharma in its full depth and range. They study Buddhist texts, even the most abstruse philosophical works that traditional Buddhism regards as the domain of monastics. They take up intensive meditation, seeking the higher stages of samadhi and insight and even the ranks of the ariyans, the noble ones.

The second way the monastic-lay distinction is being erased is in the elevation of lay people to the position of Dharma teachers who can teach with an authority normally reserved for monks. Some of the most gifted teachers of Buddhism today, whether of theory or meditation, are lay people. Thus, when lay people want to learn the Dharma, they are no longer dependent on monastics. Whether or not a lay person seeks teachings from a monastic or a lay teacher has become largely a matter of circumstance and preference. Some will want to study with monks; others will prefer to study with lay teachers. Whatever their choice, they can easily fulfill it. To study under a monk is not, as is mostly the case in traditional Buddhism, a matter of necessity. There are already training programs in the hands of lay Buddhists, and lineages of teachers consisting entirely of lay people.

Indeed, in some circles there is even a distrust of the monk. Some months ago I saw an ad in Buddhadharma magazine for a Zen lineage called “Open Mind Zen.” Its catch phrase was: “No monks, no magic, no mumbo-jumbo.” The three are called “crutches” that the real Zen student must discard in order to succeed in the practice. I was struck by the cavalier way that the monks are grouped with magic and mumbo-jumbo and all three together banished to the dugout.

I think it likely there will always be laypeople who look to the monastic sangha for guidance, and thus there is little chance that our monasteries and Dharma centers will become empty. For another, the fact that many laypeople have been establishing independent, non-monastic communities with their own centers and teachers may have a partly liberating effect on the Sangha. Relieved to some extent of the need to serve as “fields of merit” and teachers for the laity, we will have more time for our own personal practice and spiritual growth. In this respect, we might actually be able to recapture the original function of the homeless person in archaic Buddhist monasticism, before popular, devotional Buddhism pushed monastics into a largely priestly role in relation to the wider Buddhist community. Of course, if the size of the lay congregation attached to a given monastery tapers off, there is some risk that the donations that sustain the monastery will also decline, and that could threaten the survival of the monastery. Thus the loss of material support can become a serious challenge to the sustainability of institutional monasticism.

2. The secularization of life. Since the late eighteenth century we have been living in an increasingly secularized world; in the U.S. and Western Europe, this process of secularization is quite close to completion. Religion is certainly not dead. In mainstream America, particularly the “heartland,” it may be more alive today than it was forty years ago. But a secularist outlook now shapes almost all aspects of our lives, including our religious lives.

Before I go further, I should clarify what I mean by the secularization of life. By this expression, I do not mean that people today have become non-religious, fully engulfed by worldly concerns. Of course, many people today invest all their interest in the things of this world—in family, personal relations, work, politics, sports, the enjoyment of the arts. But that is not what I mean by “the secularization of life.” The meaning of this phrase is best understood by contrasting a traditionalist culture with modern Western culture. In a traditionalist culture, religion provides people with their fundamental sense of identity; it colors almost every aspect of their lives and serves as their deepest source of values. In present-day Western culture, our sense of personal identity is determined largely by mundane points of reference, and the things we value most tend to be rooted in this visible, present world rather than in our hopes and fears regarding some future life. Once the traditional supports of faith have eroded, religion in the West has also undergone a drastic change in orientation. Its primary purpose now is no longer to direct our gaze towards some future life, towards some transcendent realm beyond the here and now. Its primary function, rather, is to guide us in the proper conduct of life, to direct our steps in this present world rather than to point us towards some other world.

Just about every religion has had to grapple with the challenge of agnosticism, atheism, humanism, as well as simple indifference to religion due to the easy availability of sensual pleasures. Some religions have reacted to this by falling back upon a claim to dogmatic certainty. Thus we witness the rise of fundamentalism, which does not necessarily espouse religious violence; that is only an incidental feature of some kinds of fundamentalism. Its basic characteristic is a quest for absolute certainty, freedom from doubt and ambiguity, to be achieved through unquestioning faith in teachers taken to be divinely inspired and in scriptures taken to be unerring even when interpreted as literally true.

But fundamentalism is not the only religious response to the modernist critique of religion. An alternative response accepts the constructive criticisms of the agnostics, skeptics, and humanists, and admits that religion in the past has been deeply flawed. But rather than reject religion, it seeks a new understanding of what it means to be religious. Those who take this route, the liberal religious wing, come to understand religion as primarily a way to find a proper orientation in life, as a guide in our struggles with the crises, conflicts, and insecurities that haunt our lives, including our awareness of our inevitable mortality. We undertake the religious quest, not to pass from this world to a transcendent realm beyond, but to discover a transcendent dimension of life—a superior light, a platform of ultimate meaning—amidst the turmoil of everyday existence.

One way that religion has responded to the secularist challenge is by seeking a rapprochement with its old nemesis of secularism in a synthesis that might be called “spiritual secularity” or “secular spirituality.” From this perspective, the secular becomes charged with a deep spiritual potential, and the spiritual finds its fulfillment in the low lands of the secular. The apparently mundane events of our everyday lives—both at a personal and communal level—are no longer seen as bland and ordinary but as the field in which we encounter divine reality. The aim of religious life is then to help us discover this spiritual meaning, to extract it from the mine of the ordinary. Our everyday life becomes a means to encounter the divine, to catch a glimpse of ultimate goodness and beauty. We too partake of this divine potential. With all our human frailties, we are capable of indomitable spiritual strength; our confusion is the basis for recovering a basic sanity; ever-available within us there is a deep core of wisdom.

This secularization of life of which I have been speaking has already affected the way Buddhism is being presented today. For one thing, we can note that there is a de-emphasis on the teachings of karma, rebirth, and samsara, and on nirvana as liberation from the round of rebirths. Buddhism is taught as a pragmatic, existential therapy, with the four noble truths construed as a spiritual medical formula guiding us to psychological health. The path leads not so much to release from the round of rebirths as to perfect peace and happiness. Some teachers say they teach “buddhism with a small ‘b’,” a Buddhism that does not make any claims to the exalted status of religion. Other teachers, after long training in classical Buddhism, even renounce the label of “Buddhism” altogether, preferring to think of themselves as following a non-religious practice.

Mindfulness meditation is understood to be a means of “being here and now,” “of coming to our senses,” of acquiring a fresh sense of wonder. We practice the Dharma to better understand our own minds, to find greater happiness and peace in the moment, to tap our creativity, to be more efficient in work, more loving in our relationships, more compassionate in our dealings with others. We practice not to leave this world behind but to participate in the world more joyfully, with greater spontaneity. We stand back from life in order to plunge into life, to dance with the ever-shifting flow of events.

One striking indication of this secularized transformation of Buddhism is the shift away from the traditional nucleus of the Buddhist community towards a new institutional form. The “traditional nucleus of the Buddhist community” is the monastery or temple, a sacred place where monks or nuns reside, a place under the management of monastics. The monastery or temple is a place set apart from the everyday world where laypeople come to pay respects to the ordained, to make offerings, to hear them preach, to participate in rituals led by monks or practice meditation guided by nuns. In contrast, the institutional heart of contemporary secularized Buddhism is the Dharma center: a place often established by lay people, run by lay people, with lay teachers. If the resident teachers are monastic persons, they live there at the request of lay people, and the programs and administration are often managed by lay people. In the monastery or temple, the focus of attention is the Buddha image or shrine containing sacred relics, which are worshipped and regarded as the body of the Buddha himself. The monks sit on an elevated platform, near the Buddha image. The modern Dharma center may not even have a Buddha image. If it does, the image will usually not be worshipped but serve simply as a reminder of the source of the teaching. The lay teachers will generally sit at the same level as the students and apart from their teaching role will relate to them largely as friends.

These are some of the features of the Western—or specifically American—appropriation of Buddhism that give it a distinctly “secularized” flavor. Though such an approach to Buddhism is not traditional, I do not think it can be easily dismissed as a trivialization of the Dharma. Nor should we regard those drawn to this way of “doing Buddhism” as settling for “Dharma lite” in place of the real thing. Many of the people who follow the secularized version of Buddhism have practiced with great earnestness and persistency; some have studied the Dharma deeply under traditional teachers and have a keen understanding of classical Buddhist doctrine. They are drawn to such an approach to Buddhism precisely because it squares best with the secularization of life pervasive in Western culture, and because it addresses concerns that arise out of this situation—how to find happiness, peace, and meaning in a confused and congested world. However, since classical Buddhism is basically directed towards a world-transcendent goal— however differently understood, whether as in Early Buddhism or in Mahayana Buddhism—this becomes another challenge facing Buddhist monasticism in our country today. Looking to what lies beyond the stars, beyond life and death, rather than at the ground before our feet, we can cut a somewhat strange figure.

3. The challenge of social engagement. The third characteristic of contemporary spirituality that presents a challenge to traditional Buddhist monasticism is its focus on social engagement. In theory, traditional Buddhism tends to encourage aloofness from the mundane problems that confront humanity as a whole: such problems as crushing poverty, the specter of war, the denial of human rights, widening class distinctions, economic and racial oppression. I use the word “in theory,” because in practice Buddhist temples in Asia have often functioned as communal centers where people gather to resolve their social and economic problems. For centuries Buddhist monks in southern Asia have been at the vanguard of social action movements, serving as the voice of the people in their confrontation with oppressive government authorities. We saw this recently in Burma, when the monks led the protests against the military dictatorship there. However, such activities subsist in a certain tension with classical Buddhist doctrine, which emphasizes withdrawal from the concerns of the world, inward purification, a quest for non-attachment, equanimity towards the flux of worldly events, a kind of passive acceptance of the flaws of samsara. In my early life as a monk in Sri Lanka, I was sometimes told by senior monks that concern with social, political, and economic problems is a distraction from “what really matters,” the quest for personal liberation from the dukkha of worldly existence. Even the elder monks who served as social and political advisors were guided more by the idea of preserving Sinhalese Buddhist culture than of striving for social justice and equity.

However, an attitude of detached neutrality towards social injustice does not square well with the Western religious conscience. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Christianity underwent a profound change in response to the widespread social ills of the time. It gave birth to a “social gospel,” a movement that applied Christian ethics of love and responsibility to such problems as poverty, inequality, crime, racial tensions, poor schools, and the danger of war. The social gospel proposed not merely the doing of deeds of charity in line with the original teachings of Jesus, but a systematic attempt to reform the oppressive power structures that sustained economic inequality, social injustice, exploitation, and the debasement of the poor and powerless. This radically new dimension of social concern brought deep-seated changes among Christians in their understanding of their own religion. Virtually all the major denominations of Christianity, Protestant and Catholic alike, came to subscribe to some version of the social gospel. Often, priests and ministers were at the forefront, preaching social change, leading demonstrations, spurring their congregations on to socially transformative action. Perhaps in our own time the person who best symbolizes this social dimension of modern Christianity is Rev. Martin Luther King, who, during his life, came to be known as “the moral voice of America”— not merely for his civil-rights campaigns but also because of his eloquent opposition to the Vietnam War and his commitment to the abolition of poverty.

The advocates of engaged spirituality understand the test of our moral integrity to be our willingness to respond compassionately and effectively to the sufferings of humanity. True morality is not simply a matter of inward purification, a personal and private affair, but of decisive action inspired by compassion and motivated by a keen desire to deliver others from the oppressive conditions that stifle their humanity. Those of true religious faith might look inward and upward for divine guidance; but the voice that speaks to them, the voice of conscience, says that the divine is to be found in loving one’s fellow human beings, and in demonstrating this love by an unflinching commitment to ameliorate their misery and restore their hope and dignity.

The prominence of the social gospel in contemporary Christianity has already had a far-reaching impact on Buddhism. It has been one catalyst behind the rise of “Engaged Buddhism,” which has become an integral part of the Western Buddhist scene. But behind both lies the European Enlightenment emphasis upon righting social wrongs and establishing a reign of justice. In the West, Engaged Buddhism has taken on a life of its own, assuming many new expressions. It deliberately sets itself against the common image of Buddhism as a religion of withdrawal and quiescence, looking on at the plight of suffering beings with merely passive pity. For Engaged Buddhism, compassion is not just a matter of cultivating sublime emotions but of engaging in transformative action. Since classical Buddhist monasticism does in fact begin with an act of withdrawal and aims at detachment, the rise of Engaged Buddhism constitutes a new challenge to Buddhist monasticism with the potential to redefine the shape of our monastic life.

4. Religious pluralism. A fourth factor working to change the shape of Buddhism in the West is the rise of what has been called “religious pluralism.” For the most part, traditional religions claim, implicitly or explicitly, to possess exclusive access to the ultimate means of salvation, to the liberating truth, to the supreme goal. For orthodox Christians, Christ is the truth, the way, and the life, and no one comes to God the Father except through him. For Muslims, Muhammad is the last of the prophets, who offers the final revelation of the divine will for humanity. Hindus appear more tolerant because of their capacity for syncretism, but almost all the classical Hindu schools claim final status for their own distinctive teachings. Buddhism too claims to have the unique path to the sole imperishable state of liberation and ultimate bliss, nirvana. Not only do traditional religions make such claims for their own creeds and practices, but their relations are competitive and often bitter if not aggressive. Usually, at the mildest, they propose negative evaluations of other faiths.

Within Buddhism, too, the relations between the different schools have not always been cordial. Theravadin traditionalists often regard Mahayanists as apostates from the proper Dharma; Mahayanist texts describe the followers of the early schools with the derogatory term “Hinayana,” though this has gone out of fashion. Even within the Theravada, followers of one approach to meditation might dispute the validity of different approaches. Within the Mahayana, despite the doctrine of “skillful means,” proponents of different schools might devalue the teachings of other schools, so that the “skillful means” are all within one’s own school, while the means adopted in other schools are decidedly “unskillful.

In the present-day world, an alternative has appeared to this competitive way in which different religions relate to one another. This alternative is religious pluralism. It is based on two parallel convictions. One relates to a subjective factor: as human beings we have an ingrained tendency to take our own viewpoint to be uniquely correct and then use it to dismiss and devalue alternative viewpoints. Recognizing this disposition, religious pluralists say that we have to be humble regarding any claims to possess privileged access to spiritual truth. When we make such audacious claims, they hold, this is more indicative of our self-inflation than of genuine insight into spiritual truth.

The second conviction on which religious pluralism is based is that the different views and practices possessed by the different religious traditions need not be seen as mutually exclusive. They can instead be considered partly as complementary, as mutually illuminating; they may be regarded as giving us different perspectives on the ultimate reality, on the goal of the spiritual quest, on methods of approaching that goal. Thus, their differences can be seen to highlight aspects of the goal, of the human situation, of spiritual practice, etc., that are valid but unknown or under-emphasized in one’s own religion or school of affiliation.

Perhaps the most curious sign of religious pluralism in the Buddhist fold is the attempt made by some people to adopt two religions at the same time. We hear of people who consider themselves Jewish Buddhists, who claim to be able to practice both Judaism and Buddhism, assigning each to a different sphere of their lives. I have also heard of Christian Buddhists; perhaps too there are Muslim Buddhists, though I have not heard of any. To accept religious pluralism, however, one need not go to this extreme, which to me seems dubious. A religious pluralist will generally remain uniquely committed to a single religion, yet at the same time be ready to admit the possibility that different religions can possess access to spiritual truth. Such a person would be disposed to enter into respectful and friendly dialogue with those of other faiths. They have no intention of engaging in a contest aimed at proving the superiority of their own spiritual path, but want to learn from the other, to enrich their understanding of human existence by tentatively adopting an alternative point of view and even a different practice.

The religious pluralist can be deeply devoted to his or her own religion, yet be willing to temporarily suspend their familiar perspective in order to adopt another frame of reference. Such attempts might then allow one to discover counterparts of this different view within one’s own religious tradition. This tendency has already had a strong impact on Buddhism. There have been numerous Christian-Buddhist dialogues, seminars at which Christians and Buddhist thinkers come together to explore common themes, and there is a journal of Christian and Buddhist studies. Monasticism too has been affected by this trend. Journals are published on inter-monastic dialogue, and Tibetan Buddhist monks have even gone to live at Christian monasteries and Christian monks gone to live at Buddhist monasteries.

Among Buddhists it is not unusual, here in the West, for followers of one Buddhist tradition to study under a master of another tradition and to take courses and retreats in meditation systems different from the one with which they are primarily affiliated. As Westerners, this seems quite natural and normal to us. However, until recent times, for an Asian Buddhist, at least for a traditionalist, it would have been almost unthinkable, a reckless experiment.

Bhikkhu Bodhi

Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, ordained in Sri Lanka and currently teaching in the New York/New Jersey area. He was appointed the second president of the Buddhist Publication Society and has edited and authored several publications grounded in the Theravada Buddhist tradition. (Photo and bio by Wikipedia)