The 24th Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering

The 24th Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering

The 24th Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering was held at Spirit Rock Meditation Center, just over an hour north of San Francisco, California. Sheltered from the hustle and bustle of the big city, green rolling hills provided a quiet, peaceful container for this annual meeting of monastics from various Buddhist traditions.

Participants of The 24th Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering (Photo © 2018 Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering)

We numbered 41 monks and nuns, from the Theravadin tradition, the Chinese Zen tradition, the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives (Soto Zen), various lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, and the Thilashin (Sayale) tradition (10-precept holder) of Burma.

Unlike our monastic ancestors, who lacked modern transportation and means of communication and who didn’t speak a common language, monastics living in the West have the ability to meet together, learn about one anothers’ traditions, and practice together. The friendships that develop among us are precious and help us in the adventure of bringing the Dharma and the monastic way of life to a new culture. All this bodes well for Buddhism in the West.

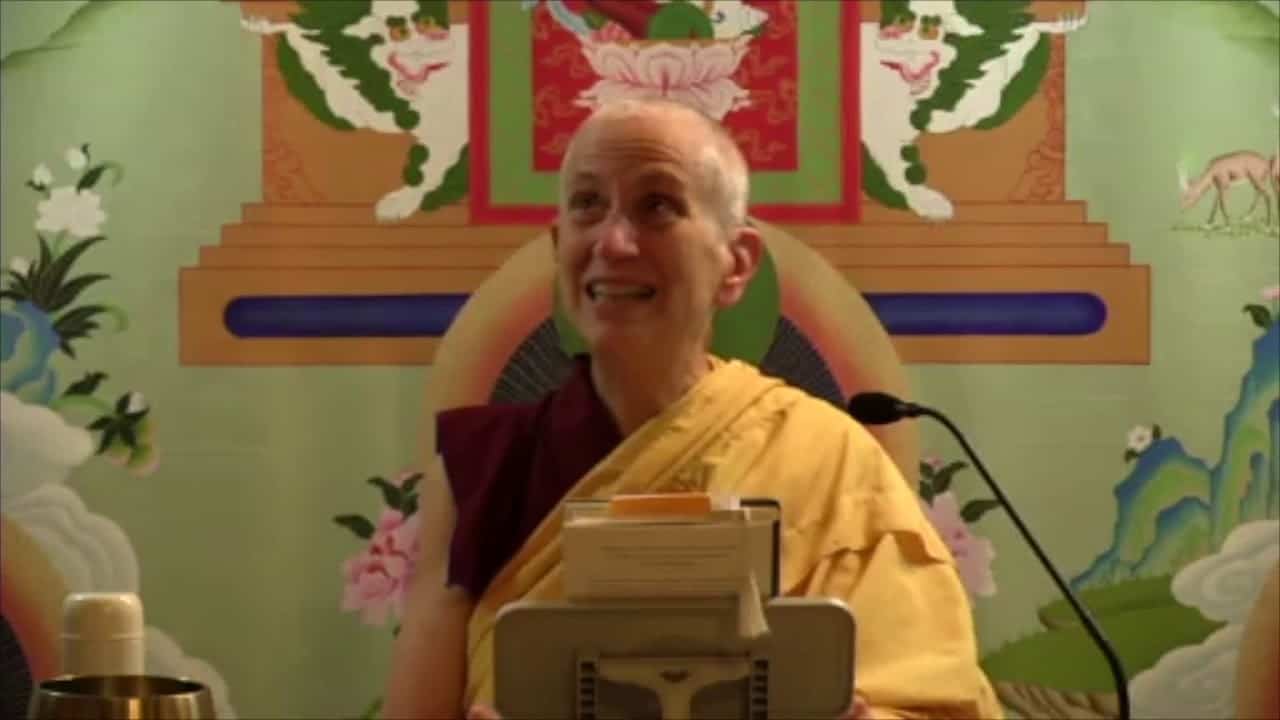

The gathering provided three and a half days for communal practice and sharing, this year’s theme being “Practice, Path and Fruit.” Day One began with a panel discussion on the “Ground of Practice,” posing the question, “How do our traditions define meditation and its development towards awakening?” Venerable Sangye Khadro of the Tibetan tradition, Venerable Jian Hu from the Chinese Zen tradition (Lingji lineage), and Bhante Jayasara of the Theravada tradition shared their thoughts.

Venerable Khadro explained the general division of meditation in the Tibetan Buddhism into stabilizing or shamatha meditation, and analytic or insight meditation. Both forms of meditation are necessary to attain awakening: the attainment of shamatha to sufficiently subdue the mind so it can focus single-pointedly on an object, and analytic meditation to directly realize the nature of reality.

Bhante Jayasara explained the centrality of mindfulness practice in the Theravadin tradition: specifically, mindfulness of body, feelings, mind and phenomena. This form of mindfulness meditation can be done when one is in any of the four positions: walking, standing, sitting, and lying down. To complement this, the practice of metta, or loving-kindness, is an important pathway towards awakening, providing the fortitude for one to remain peaceful and be of benefit to others, regardless of external circumstance.

Venerable Jian Hu provided insight into the overall approach of Chan meditation practice, which can be considered a unique unification of shamatha and vipassana. In any activity—whether it be formal sitting practice, watching the breath, eating, walking or working meditation—shamatha and vipassana can be combined through the union of single-pointedness and analysis. Venerable Jian Hu also explained two practices emphasized in the Lianji house of Chan in which he trained—Gong An (Koan) and Hua Tou.

In the evening of Day One, Reverend Vivian from the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives was invited to speak on “Weathering the Storms”—the obstacles she had encountered in her monastic life, and how has she been able to work through them. Reverend Vivian first spoke of her early struggle to work with the anger that arose soon after she ordained. In this instance, she could see the power of living in the monastery, as the disadvantages of anger for oneself and others are easy to see and necessary to remedy in the container of communal living.

Reverend Vivian also touched on the “storm” that was the unexpected disrobing of her preceptor and teacher, in a tradition where the disciple-teacher relationship is paramount. Eight years after the fact, Reverend Vivian spoke in a calm and clear manner of how such an occurrence puts it back to the students to find refuge and resources within themselves. By doing so, the students’ strength of mind and determination to practice is enhanced, with the confidence that nothing can shake them from the path.

Day Two provided a chance for sightseeing and connection: Spirit Rock had organized volunteers to ferry the monastics to the nearby Marine Mammal Center, followed by a beach walk. At the Center, we were received by the Executive Director, Dr. Jeff Boehm. Jeff gave a presentation on the significance not only of the activities of the Marine Mammal Center in terms of the rescue and rehabilitation of animals, but also the transformation of the site itself—from what used to be a military aircraft hanger to what is now a place of healing and love.

Following the presentation, the monastics were invited to enter the normally closed-to-public quarters of the animals, to quietly circle their pens and recite the Heart Sutra mantra (tadyatha om gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha) and the mantra of compassion (om mani padme hum).

That evening, a second panel was held on the topic of “Path of Practice,” posing the question, “What does our personal path look like, and how does monastic life enhance our practice?” Ayya Santussika Bhikkuni of the Theravada tradition spoke first, sharing the story of how she came to monastic life, following in her son’s footsteps who had ordained first. She expressed great gratitude for the focus monastic life provides for practice, and the wish to continue in this lifestyle up to awakening.

Reverend Kinrei, of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, focused on the importance of motivation. Ordained for almost 40 years, Reverend Kinrei had spent almost equal time living in a monastic community (Shasta Abbey) and living alone at a priory where he is currently responsible for guiding the local lay community in their study and practice of the Dharma.

Regardless of living circumstance, Reverend Kinrei condensed his practice to cultivating a kind heart and a good motivation, no matter what you are doing. The distinction and difference between on-the-cushion and off-the-cushion periods appear to have less significance as the years progressed. Rather, the various rituals and ceremonies that are a part of monastic life serve as a tool to stop, pause, and check-in about the state of one’s mind—and to transform it to a virtuous state if it’s not already there.

Venerable Thubten Tarpa of Sravasti Abbey, practicing in the Tibetan tradition, echoed Reverend Kinrei’s emphasis on watching the mind, beginning her sharing with a quote from Togme Sangpo’s text, 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas:

In short, whatever you are doing ask yourself What’s the state of my mind? With constant mindfulness and mental alertness, accomplish other’s good.

Having lived in the monastery her whole ordained life, Venerable Tarpa described communal life as a 24/7 endeavor of practice and training. A key supportive element to this “rock tumbler” environment has been role models: both living teachers as well as inspirational texts from masters of the past.

Day Three began with the final panel discussion on the topic of “Fruition in Our Times.” Panelists were posed the question, “Bhikkhu Bodhi once said that our only job was to become enlightened. Have we set the conditions for ourselves, for our communities and those that follow?”

Bhante Suddhaso of the Theravada Thai Forest Tradition spoke strongly about the need to make monastics easily accessible to lay Buddhists, in environments that do not pose cultural or social barriers. Dress codes, gender segregation and unfamiliar etiquette were identified as potential stumbling blocks that stand in the way of Buddhism flourishing in the West in the long term.

In contrast, Reverend Seikai of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives emphasized the need for forest monasteries to continue into the future. From his perspective, such a model of monastic life and training provides conducive conditions to focus on inner transformation, and does not render the teachings of the Buddha inaccessible.

Venerable Gyalten Palmo of the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition took a different slant in her presentation. Grounded in the Mahayana teachings, she rejoiced at how the Buddha’s teachings on love, compassion and bodhicitta continue to this day, with many practitioners—lay and monastic—creating the causes to attain the full awakening of Buddhahood.

The afternoon session of the final day of the gathering began with a special ceremony of appreciation for the Spirit Rock volunteers who made our stay possible. Over 20 volunteers joined us in the shrine room—about one volunteer to every two monastics!—to receive our communal thanks. Shasta Abbey and Sravasti Abbey offered prayers used in their monasteries to thank volunteers for their service, followed by the Theravadin monastics reciting a blessing in Pali.

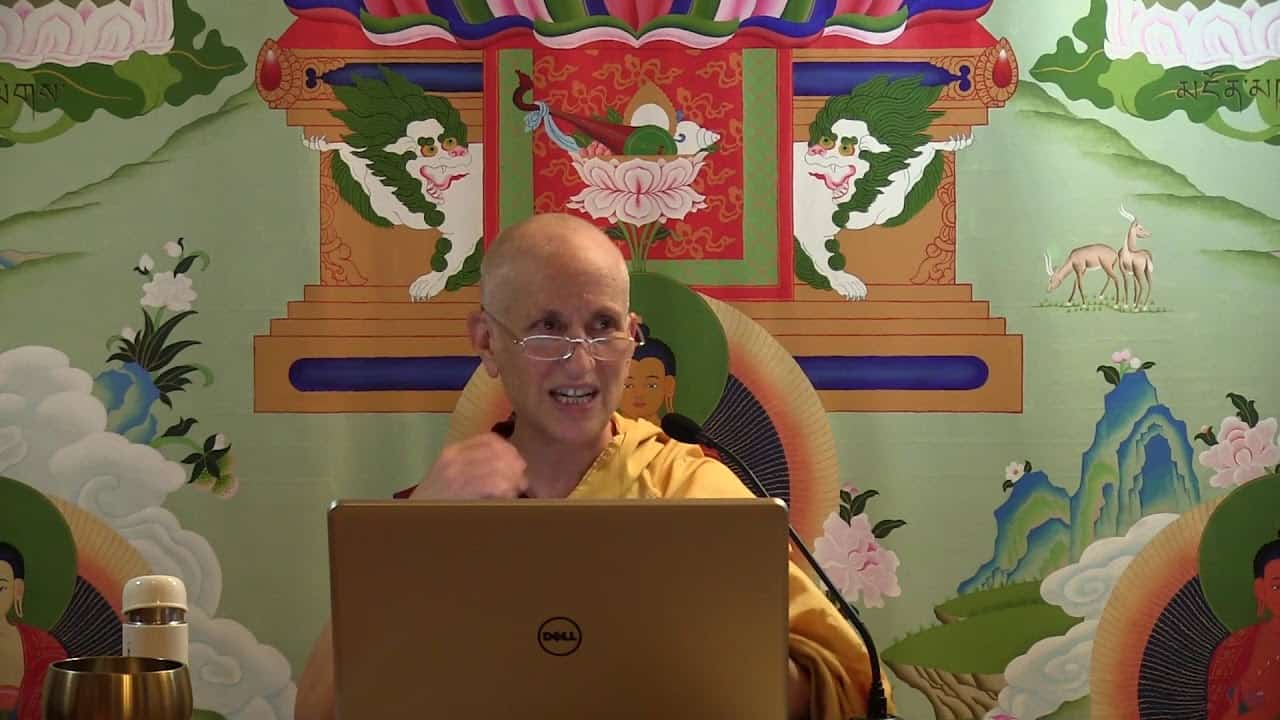

Following this, Venerable Thubten Chodron spoke to the topic “Working on the Ground, Seeking the Path, Aspiring for the Fruit.” In this last formal talk of the gathering, Venerable Chodron touched on a variety of topics, drawing on ideas and concerns expressed by participants throughout the week. One such topic was the establishment of monastic communities in the West. She shared stories from the many years and various storms that arose in the lead up to the founding of Sravasti Abbey in 2003, and the 15 years that have since followed. Venerable Chodron also shared wisdom around working with expectations, the composition of a 501(c)3 with board members, the monastic study program and training model, as well as the vision going forward—including succession planning.

It was clear from the many questions throughout and after the talk that the establishment of monastics communities in the West is a topic dear to people’s hearts—and that with Buddhism still relatively new in the West, there is a need to share experience of what has and has not worked in such an endeavor.

In addition to these formal talks, the organizers arranged various alternate forms of interaction. On two occasions, walking meditation was offered: in the Thai Forest Tradition with Nuntiyo Bhikku, and in the Soto Zen tradition with Reverend Amanda Robertson.

The format of open space dialogue was also used, to allow topics for group discussion to organically arise and evolve. Over the three days, three open space sessions were held, covering topics such as: how to practice and provide guidance in current ethical crises; living the Vinaya in modern times—what adaptations have been made, and do they work?; how identity politics relates to the Buddha’s teachings on emptiness and deconstructing the self; sexual abuse in the sangha and how to intervene; gender and ordination; and much more. Our discussions were lively and informative as we spoke of issues common to all of us.

The last morning of the gathering began with a circle of appreciation, each monastic expressing their gratitude for the opportunity to connect and learn with their brothers and sisters in the Dharma. The unique and precious forum the gathering provides was expressed in the tears of two newly ordained monastics currently living on their own while connected to a local Dharma center.

A brainstorm for next year’s topic and location followed, with the group settling on a theme inspired by the closing three refuges dedication prayer led by Venerables Jian Hu and Jian Hong Shi:

I take refuge in the Sangha. May each and every sentient being form together a great assembly, one and all in harmony.

Everyone departed uplifted and inspired in their own practice, in their monastic practice, and in their efforts to share the Buddha’s teachings with others.

More information about the location, time and topic of the next Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering will be available by the end of the year. You can visit https://www.monasticgathering.com/ for such information, and to view more photos of this year’s gathering.