More precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel

More precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel

Part of a series of short Bodhisattva’s Breakfast Corner talks on Langri Tangpa’s Eight Verses of Thought Transformation.

- Setting the tone of bodhicitta

- How developing bodhicitta depends on love and compassion for all sentient beings

- Loosening our rigid concepts of who people are

- The importance of applying these teachings in our lives

Right after the Chenrezig retreat ended Venerable Lobsang, I think on behalf of the community, asked me to go into the eight verses of mind training. So I thought I would do that now. I can give a long explanation, a short explanation. I’ll try and do a medium one, but we’ll see what happens.

The first verse says:

With the thought of attaining awakening

For the welfare of all beings,

Who are more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel,

I will constantly practice holding them dear.

This is the verse that sets the tone for everything. This is the verse of generating bodhicitta, which is, they say, to be the cream of the Buddha’s teachings. If you churn the Buddha’s teachings, the cream that rises to the top is bodhicitta. That is the thought of attaining awakening for the welfare of all beings. That’s what bodhicitta is.

All these beings that are more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel. I explained during the retreat—this will be a little bit of a repetition for those of you who attended the retreat—that in ancient Indian mythology there’s this idea of a wish-fulfilling jewel that’s somewhere in the ocean. They used to send exploratory ships out to try and find it. The idea being if you found a wish-fulfilling jewel, it would fulfill all your wishes.

Here it’s saying that all these sentient beings are more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel. More precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel that could fulfill all of our worldly wishes. This jewel can give you whatever you want in a worldly sense, but it can’t give you nirvana, or awakening, or any kind of spiritual progress. But these other sentient beings are more precious than this wish-fulfilling jewel because based on them we can attain all the paths and stages, as well as full awakening.

Then we say, “Well why are these sentient beings more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel? Why?”

It’s because to generate bodhicitta, which is the motivation that we need to get ourselves to awakening, and the motivation that differentiates someone on the Mahayana path from someone who aims simply for arhatship, this bodhicitta depends on our having love and compassion, and wanting to work for the awakening, of these sentient beings. It’s not just “sentient beings.” It’s all sentient beings, which means each and every one. It includes us. But it also includes everybody.

So if you think of the latest thing going on in the country, and this is never going to go out of style for the next two years or something because every day there’s a new something happening…. The latest one is all these sentient beings—well especially one, well two of them who are really good buds—our enlightenment depends on them. We can’t get enlightened if we leave even one sentient being out of our bodhicitta.

It’s in that way that each one of them is more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel. Because without our having love and compassion and so forth for each and every one of them, our whole spiritual progress to awakening is going to have huge interruptions. We’re not even going to be able to enter the first of the five Mahayana paths, the path of accumulation, because we won’t have bodhicitta.

Then the question comes: How in the world do I see these sentient beings as precious? How in the world do I cultivate love and compassion for them when they’re such…whatever name you happen to want to call them? Or adjective you want to attribute to them. How do I do that?

Here we have to do a little bit of groundwork before we even get into the meditations to develop bodhicitta. We have to loosen our very rigid concepts that how somebody is, who appears to us now, is how they’re always going to be. In other words, each sentient being is always going to be the sentient being that appears to us now. And that is not so, because we all get reborn. Who we are now dies. The general “I” goes on to future lives, but the person right now that we consider such a jerk, that person doesn’t go on to the next life. Their mere “I does, the continuity of their subtle mental consciousness. Not even their gross mental consciousness goes on to future lives. The aggregates of this life cease at the time of death. It’s only the extremely subtle mind that goes on.

When we really think about that, then we see whoever they are now that we don’t like, or disapprove of, or feel threatened by, or whatever, that person isn’t going to be the person who they are in the future lives. They’re going to be an entirely different person.

That means that who they are this lifetime—even before they get reborn—is not something that’s permanent and self-existent. Even in this lifetime, who they are in this moment is not who they have always have been. Here’s when it becomes very helpful to think of that person being a baby. (England did that very well [laughter]). Think of them being a baby. Or think of them being old and senile. (Which also isn’t terribly difficult….)

What I’m getting at is whoever they are now isn’t who they’re always going to be, so let’s not concretize who this person is, whoever they may be, because whoever they are is something that’s transient, impermanent, and also was created by causes and conditions. They’re just a product of causes and conditions. They’re nothing that is fixed, because causes and conditions are always changing, so the result is always changing.

In other words, I think some awareness of emptiness and some awareness of impermanence are really necessary if we’re going to cultivate bodhicitta. Otherwise we get too locked into our judgments of people based on how they appear to us at this very moment, with all our wrong conceptions chipping in and contributing to the situation.

I was writing to one of the inmates that I correspond with, and he had told me about a situation that happened when he was 16 that really made a strong impression on him. His father scolded him for something that really didn’t deserve scolding, but then told him, “You’re not going to amount to anything,” and, “you’re flawed,” and blah blah. Really tore him to shreds. At that delicate age of 16, when you’re just trying to figure out who you are. After that he really went downhill, and he started getting involved in gang things and all sorts of stuff. He was telling me there’s something still very hard in his heart about that situation that happened 25, almost 30 years ago.

I recommended him seeing that his father now is not the same as that person. His father now feels very torn because his son has spent most of his adult life in prison. And he as the son does not want to cause his father any more pain, because his father’s becoming elderly. But he wants to dissolve this thing that happened before. So I said, really see that the father you have now is not the same person that said that to you. And that the person who said that to you was impelled by his previous causes and conditions. And though he probably didn’t consciously say “I want to adversely affect my son and make a very strong negative imprint on his life.” Due to his own afflictions, he said something and that’s what happened. Sometimes his father would bring up situations that reminded him of that, and it was very hard for him. So I said, “Just see your father as who he is today, not who he was then.”

He said at the next family visit he tried doing that and it really helped him a lot, because he began to see that what happened in the past was in the past. His father doesn’t think that and isn’t going to say that now. And his father said that due to his own frustration over who knows what happened that day many years ago.

You see, seeing things as impermanent, seeing that people change, realizing that they aren’t truly existent, that really helps on the forgiveness side. And in order to have compassion for others, we have to be able to forgive them. If we can’t forgive them and put down our anger, it’s going to be very difficult to create compassion, because anger and compassion can’t exist ever, manifest, in one mindstream at the same time. They’re contradictory. And mutually exclusive. But not a dichotomy.

We have to really practice like that, and loosen this very strong opinion that we have of who people are, as if they had one essence that is who they always have been and who they always will be. That will help us practice holding them dear.

That’s a start on the first verse.

Again, this is stuff to practice. It’s not just to hear the BBCorner talk and then on to the next thing. But really to apply this in our meditation and bring up people and instances that still cause us discomfort when we think about them, so that we can try seeing the people involved in a totally different way, in a more expansive way, instead of as some permanent, inherently existent whatever we want to call them. And if you do this–and it takes time, we need to practice, it’s not just one meditation session, it’s repetition, again and again–but as we do this, and change our feelings about these people, everything in our life really begins to change. It really can have very powerful effects on many aspects of our life.

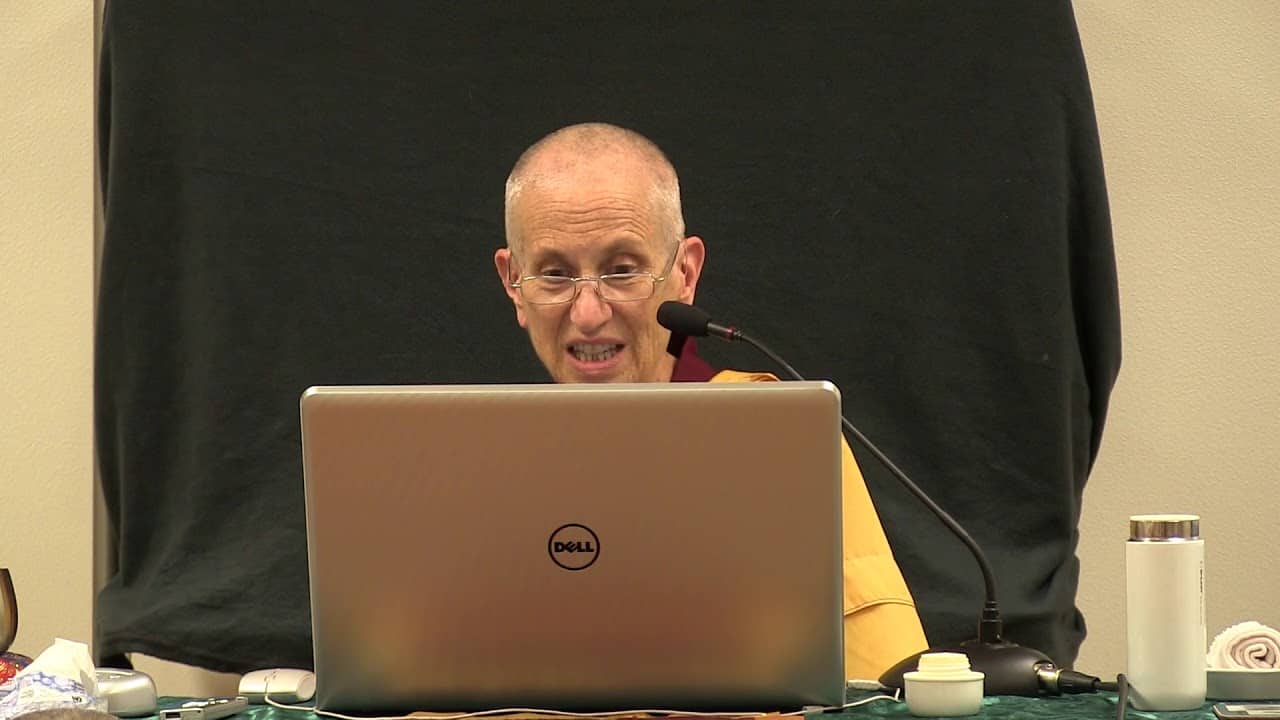

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.