Becoming a bhikshuni

Becoming a bhikshuni

In November, 2017, Venerable Pende and Venerable Losang went to Taiwan to receive bhikshuni and bhikshu ordination respectively. Below Venerable Pende shares her experience. It was challenging and rewarding and we can see the changes in her.

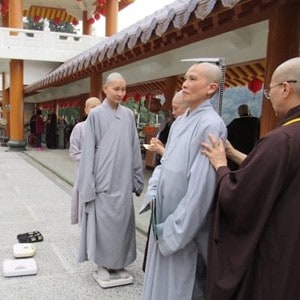

Arriving at Lingyan Temple, Ven. Pende is measured for the outer robes that the temple will provide. (Photo by Sravasti Abbey)

Thank you very much for this opportunity to share my unforgettable experience becoming fully ordained in Taiwan. Even though it has been over three months since I came back to the US, the experience is still vivid in my mind. I never thought that I would go to another country to become fully ordained, but it did happen. I was excited about it, but at the same time I was nervous because they speak Chinese in Taiwan, and I don’t know Chinese! The full ordination event was very organized, well-planned, and conducted with great reverence. This is why many monastics from Southeast Asia dream of going to Taiwan for their ordination. When I shared pictures of the ceremony with my family and friends, they were very impressed. I feel very grateful and honored that I had the great fortune to be ordained there.

The ordination temple, Lingyan Zen, is in the southwest part of Taiwan–about a four-hour drive from Taipei. It is up in the mountains and the view is magnificent. One of the nuns from Dharma Drum Mountain told me that the temple was of medium size, but to me it seemed quite big. Its Buddha Hall held 375 monastics from several countries during the ordination ceremony.

Even though two thirds of our Abbey’s community have already become fully ordained in Taiwan, I would like to give a little background for those of you who will be going there soon. To receive full ordination, all candidates have to go through the triple platforms. The first platform is the sramaneri/sramaneras ordination, the second platform is the bhiksu/bhiksuni ordination, and the third one is the bodhisattva ordination. Unlike male candidates, female candidates have to go to the dual sangha – first the bhiksuni sangha and then the bhiksu sangha – on the same day in order to receive their formal bhiksuni certifications. To me, the bhiksu/bhiksuni ordination was the most challenging because I was questioned twice about my personal hindrances while in a small group of three candidates in front of ten masters. According to the Nansan School, hindrances to receiving the precepts consist of thirteen grave hindrances and thirteen minor ones. If a candidate has just one of the grave hindrances, he or she is disqualified from receiving either the sramaneri/sramaneras precepts or bhiksu/bhiksuni precepts in this lifetime. As for the minor hindrances, they are not permanent, and once removed, a candidate is allowed to receive the sramaneri/sramaneras precepts or bhiksu/bhiksuni precepts.

I felt overwhelmed and frustrated the first few days after I arrived at the ordination temple. Not knowing the language was one of my biggest challenges during the entire ordination period. Because I did not know what was going on, I just followed what people around me were doing. A few days later, I decided that I’d better learn the Chinese commands that were being given rather than simply imitating others. In addition, I am a slow eater. I had to adjust my eating habits to eat faster and eat less so that I could finish before they rang the gong. Their dining etiquette was different than what I have been accustomed to, and I had to learn new rules. For example, one rule is that people have to take everything they want to eat at the beginning of the meal because someone collects the leftovers as soon as he or she notices them. At first, I forgot about this and ended up eating much less than I wanted. I was starving for a few days because I have high metabolism and I didn’t know how to ask for more food in Chinese. As time went by, I learned to be patient and calm as it took time to become familiar with things that were completely new to me.

Needless to say, the daily routine was arduous. Our daily wake-up time was 4:20 am, which may have caused some people to become exhausted. While we were chanting early in the morning, I saw a few nuns faint and fall down on the floor like a tree falls on the ground. People tried to help them get up, but they fell down again. Even a monk had to be carried out of the Buddha Hall because he was unconscious. A week went by and more than two-thirds of the participants caught a cold or flu–as evidenced by the face masks they were wearing. I heard that some people became so seriously ill that they had to go to the hospital.

The 35-day training for full ordination was intense but at the same time very enriching. The daily schedule was well-balanced. We spent time learning about the precepts, rehearsing for the actual ordination ceremony, training on dining etiquette, practicing the wearing of precept robes and spreading the sitting cloth, chanting twice a day, engaging in repentance and meditation, and offering services. Surviving this strenuous training required mental and physical strength, fortitude, flexibility, and ethical discipline. After the opening ceremony, my ankles were swollen and very painful because I had to stand for two hours without a break. I don’t think anybody with a weak mind or body would be able to make it through training and endure standing for over an hour during morning and afternoon chanting, kneeling on a hard cushion over one and a half hours when taking the bodhisattva vows, or making prostrations for almost three hours during repentance before the actual ordination. Last but not least, having incense burned on my head prior to the actual bodhisattva ordination required courage and determination. By meditating on the breath, I stayed calm and experienced the heat spreading on top of my head. It was very hot! I rejoiced that my full ordination went smoothly without obstacles and I was able to attend all the events and sessions.

Near the end of the ordination program, we posed for a group photo. The professional photographer had to blow a whistle to direct our huge group and make sure that everyone’s face appeared in the photo. A few days later, we were taken to downtown Chaiyi, a large city about 25 minutes from the ordination temple, for an alms round. Many local people came out to greet us and make a dana offering. We walked for over an hour and eventually had lunch at a very good vegetarian restaurant before heading back to the temple. Other sites I was able to visit during the trip included the Grand Buddha Hall, the Kuan Yin Hall, the library (one of the biggest Buddhist libraries in Taiwan), and the world’s biggest bell at the Dharma Drum complex, the Luminary International Buddhist Institute, and the Pu Yi nunnery.

While the language barrier prevented me from understanding the entire ordination program, at least the teachings on the precepts were translated into English, for which I’m grateful. However, not knowing the language is not always bad. Because I couldn’t communicate with five out of six of my roommates, I had more time to study, rest, and conserve energy. My main focus was to learn how to answer the 26 questions for the individual hindrances that were to be examined at the second platform. With a little knowledge of Chinese and with help from the Dharma Drum Mountain nuns and my roommates, I was able to understand the questions and answer them even though they were asked out-of-sequence.

Becoming fully ordained in Taiwan has taught me several valuable lessons:

- If I cannot communicate with others using spoken language, I can make a connection with sign language, a smile, a small act of kindness, politeness, or simple courtesy.

- When visiting a new place, such as Taiwan, it’s wise to adopt the philosophy, “while in Taiwan, do as the Taiwanese do.”

- It’s important to remember how the kindness, generosity, and hospitality of numerous people helped me overcome many challenges.

- It’s good and humbling to laugh at myself for the mistakes I made because I did not understand the language.

- I must appreciate deeply what my parents taught me–when I go somewhere, I must act appropriately and behave well because I represent my family, my community, and my country.

- To me, routine life can get a little boring. Once in a while, stepping out of my comfort zone and facing new challenges keeps me inspired and makes me mature in my capacities to contribute and serve others.

- It’s wise to let go of resentment and anger due to gender inequality or ordination order discrimination.

- I followed rules, instructions, protocols, and etiquette – not because I wanted to avoid being scolded or told to kneel on the marble floor during chanting, but because I wanted to be attentive to my behavior and manners.

- Every day, I practiced kindness, consideration, generosity, and hospitality, and I received the same treatment from others.

- Finally, I want to mention how deeply touched I was by the tremendous generosity of thousands of donors who came to the ordination temple to make offerings to us. Receiving such abundant material offerings reminded me to practice diligently in order to repay people’s kindness.

I would like to thank Venerable Chodron and all the community members for showing me kindness, generosity, and support for my full ordination. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their encouragement and rejoicing in my accomplishment.

I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the ordination organization, the ordination temple, Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts, Dharma Drum Mountain sangha, Luminary International Buddhist Institute, Pu Yi nunnery, all the lay volunteers, and all the donors for making my ordination memorable.

At a personal level, having received the bhiksuni ordination has deepened my commitment to the spiritual path, fostered my spiritual growth, and broadened my appreciation of the differences in Buddhist traditions. At a broader level, being a bhiksuni has strengthened my inner sense of responsibility and integrity to uphold the Dharma and the Vinaya in order to contribute to the flourishing of Sravasti Abbey and Dharma in the West.

In retrospect, going through the difficulties of the month-long triple ordination program helped me strengthen my motivation to become a bhiksuni, to serve sentient beings, and to contribute to the flourishing of the Dharma. If I had gone to a short program that was easier and lacked the rigorous training, I wouldn’t have appreciated the privilege and responsibility becoming a bhiksuni entails.