More qualities of the Buddha

More qualities of the Buddha

Part of a series of teachings on the text The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for Lay Practitioners by Je Rinpoche (Lama Tsongkhapa).

- Verses praising the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind

- Why we praise the Buddha’s body and not just his mind

- The types of buddha bodies

- Qualities of the Buddha’s speech

The Essence of a Human Life: More about the qualities of the Buddha (download)

To continue talking about refuge, I wanted to talk a little bit more about the qualities of the Buddha and relate that to one verse that is often used in the Tibetan tradition to praise the Buddha.

That verse goes:

I bow my head to the chief of the Sakyas,

whose body was formed by the 10 million perfect virtues,

whose speech fulfills the hopes of limitless beings,

whose mind sees precisely all objects of knowledge.

It’s praising the Buddha by way of his body, speech, and mind.

The first line, “I bow my head to the chief of the Sakyas,” that’s referring to Shakyamuni Buddha. The Sakya clan, and then he’s the chief, meaning not that he’s the political chief, but he’s the exemplar of the beings that came from that clan.

And then the next line, “Whose body was formed by 10 million perfect virtues.” The Buddha’s body is not like our body. There are two buddha bodies. One is the samboghakaya (or resource body, or enjoyment body)—that’s the form the Buddha appears in in pure lands to guide the arya bodhisattvas. Then there’s the emanation body which is the form he appears in that we ordinary beings perceive.

The Buddha’s samboghakaya (or resource body) is formed from the extremely subtle wind of the bodhisattva that became that body.

In terms of us, we have an extremely subtle mind and an extremely subtle wind that are one nature, different isolates (nominally different), and that is what is the basic (you could say) buddha nature that allows us to gain the Buddha’s mind and the Buddha’s body. Our extremely subtle mind, when it’s fully purified, becomes the the Buddha’s mind. Our extremely subtle wind, when the mind is purified and the wind is purified, becomes the samboghakaya, the resource body (or enjoyment body) of the Buddha.

To have that kind of body, it says it’s the source of 10 million perfect virtues. Actually, that’s underestimating it. In Precious Garland (we’ll get to that later) they say it’s due to countless virtues, you can’t count that high. And there’s a whole section in the Precious Garland where it goes through what the causes are for the 32 signs on a buddha’s body. The whole conclusion at the end of it is that it’s inestimable. It’s not infinite, because there is an end, but it’s just so much that you can’t conceive of it. This comes not from doing physical exercise—that’s not how we perfect our body and transform it into the Buddha’s body—but through our mental practice. Because when you purify the mind then the wind that is the mount (or the vehicle) of that mind gets purified as well. From that you get the enjoyment body. And from the Buddha’s enjoyment body then comes the emanation body, which is a grosser form that we ordinary beings can communicate with.

For example, a supreme emanation body would be the Buddha who appeared on our earth. Other emanation bodies: people who would regard His Holiness the Dalai Lama as one of those. And then there are other beings who are buddhas who manifest that we encounter, but they don’t necessarily identify themselves to us. This all comes from the purity of the mind.

I thought for a long time…. Because there are some verses, like the verses that we chant before teachings, a lot of them praise the Buddha’s body. And I was always going, “Why are they praising the Buddha’s body? It’s really his mind that’s important. The body is not so important.” Then I began to understand, well, they praise the body, I think, for a couple of reasons. One is that the causes of the body have to do with the mental Dharma practice, so it actually implies improving the state of mind. And second of all, for some sentient beings the beauty of the Buddha’s body is what really grabs their attention and makes them want to practice the Dharma. Because you read accounts in the Pali scriptures of somebody just seeing the Buddha and going, “Wow, there’s something special about this guy. What’s he teaching?” Or they see how some of the Buddha’s disciples walk, how they behave, and they go, “There’s something unusual about these people.” And the people haven’t said a word, it’s just their physical, bodily behavior that’s making an impression.

I realized, that it is something really important that is a way to get sentient beings interested in the Dharma. And especially if you’re somebody who has a lot of physical pain and problems with your body, the idea of having a purified body that’s mental in nature, that is very beautiful and is not made of this kind of substance that gets old and sick and dies, for a person who’s really stuck with a lot of physical stuff this life, the image of having a buddha’s body really captivates their attention and makes them want to practice. So that’s the conclusion I came to, in case any of you are like me, wondering about why all the praises to the physical body of the Buddha or the physical body of any of the deities.

The second line says, “Whose speech fulfills the hopes of limitless beings.” Now, for me, when I think of the Buddha’s speech, “Oh yeah, that’s the kind of speech I really want to have.” Because they say that when the Buddha speaks, first of all, everybody understands it in their own language and you don’t need to wear these things (headphones). What a relief. But even more than that, the Buddha’s speech, each sentient being understands it in a way that is most appropriate for them at that particular time.

I just look at my speech, and sometimes I have a good motivation but the words don’t come out right and people misunderstand them, and they get upset. Or I say the wrong thing that pushes somebody’s buttons when I’m actually trying to soothe them, but I do the opposite. Sometimes looking at our speech, even when we have the motivation to help, our speech comes out all skewed and all wrong, and it causes conflict, and it causes misunderstanding and disharmony. And then when we’re in a bad mood our speech is harsh and we pout and we complain and we grumble, and all of that. Which certainly doesn’t spread happiness and joy in the world.

You think of the Buddha’s speech and, first of all, all of that kind of pouting and grumbling and shouting and screaming, that isn’t present at all. A buddha may speak very strongly to get the point across, but it’s not motivated by anger or rage or anything like that. But the Buddha knows what to say at what time. The right time to say the right thing to the right person that will benefit them. And just having that kind of finesse and subtlety, wow, I think that would be fantastic to have that kind of quality of speech.

They say that’s why when somebody who has realizations, when that person teaches, they may say the exact same words as somebody who doesn’t have realizations, but the person with realizations, their speech affects people in a way that the person without realizations, who says the exact same words, their speech doesn’t affect other people in the same way. Because there’s power behind the words according to the mind that is saying them.

One of the names people often get is Ngawang. Ngawang means “powerful speech.” To have that kind of powerful speech to really be able to benefit others, I think, would just be amazing. You could do so much good. And they say that the Buddha’s speech is the basic and the most important way through which an enlightened being benefits us sentient beings. It’s by teaching us the way to practice so we can liberate ourselves. So having that kind of speech is important. And therefore, admiring the Buddha who has that kind of speech, and trying to create the causes to have that kind of speech ourselves, is very important.

And then the last line says, “Whose mind sees precisely all objects of knowledge.” “Objects of knowledge” means all objects that are knowable. In other words, everything that exists. A buddha can see precisely everything that exists. In other words, a buddha is omniscient. From the Mahayana viewpoint a buddha doesn’t need to turn his mind to some topic for that omniscience, or knowledge, regarding that topic to arise. But that omniscient mind, that knowledge, is there all the time.

Again, when you think, “Wow, if I had that kind of mind….” Again, how much good we could do in the world! Because the speech may say the right thing at the right time, but the mind is the one that guides the speech. So we need to know that. And to know how to say the right thing at the right time, we need to know sentient beings’ dispositions. Because people have different dispositions, different tendencies, different interests. So we need to know all the kind of variety of sentient beings. And they aren’t nice easy categories that you can fit everybody into, because each individual is his own category. But to be able to know that so that you know exactly how to guide different sentient beings. When to answer a question and when not to answer that question. When to answer the question this way, when to answer the question that way. When to encourage questions, when to say “no questions.”

To guide sentient beings we have to have this kind of incredibly subtle ability to tune into where they’re at, and also to know their karma, what their potential is. What potentials could ripen soon. What potentials need to be enriched and will only ripen later. So to know not only their dispositions but to know their karma. To know which sentient beings we have a closer connection with.

Each buddha, of course, has impartial love and compassion for all beings, but because when they were ordinary beings like us they may have had different karmic relationships with different beings, then they can especially help certain beings. But to know which sentient beings we have that special karmic relationship with, again, we need some supernormal powers. Then even if we know, “Oh, there’s a special karmic relationship,” then to have the impartial love and compassion that doesn’t make us go, “Oh well, I’ll just manifest and help these beings, and somebody else can help the rest.” No, a buddha manifests in whatever way is possible to help each and every living being. So to have that kind of impartiality, that love, that compassion, that great resolve that is determined to bring that about.

All these kinds of qualities are qualities of a buddha’s awakened mind, that, of course, we want to admire. Because when we admire and respect those qualities, it helps us create the causes to generate them. But also to hold in our minds an aspiration to have those qualities. And then to really study and ask ourselves, “Well, what kind of causes do I need to create to have those qualities?”

We can see through just reading this verse of praise to the Buddha that a buddha’s body, speech, and mind can do so much incalculable good in the world. And let’s go for it. And we also need the guidance of a fully awakened being like the Buddha in order to know what the path is to become like that ourselves.

Let me read the verse again:

I bow my head to the chief of the Sakyas,

whose body was formed by the 10 million perfect virtues,

whose speech fulfills the hopes of limitless beings,

whose mind sees precisely all objects of knowledge.

Let me just go back to, “speech fulfills the hopes of limitless beings.” Again, limitless, countless beings. And the speech is not partial. It’s not just fulfilling the hopes of some beings. And “fulfilling the hopes” means teaching them the Dharma so that they can be free of samsara themselves. It doesn’t mean fulfilling the hopes like, “Johnny wants a baseball bat for Christmas,” and so Buddha’s speech fulfills that hope. That’s not what it means. It means really teaching so that we can take control of our own lives and create the causes for the kinds of results we want.

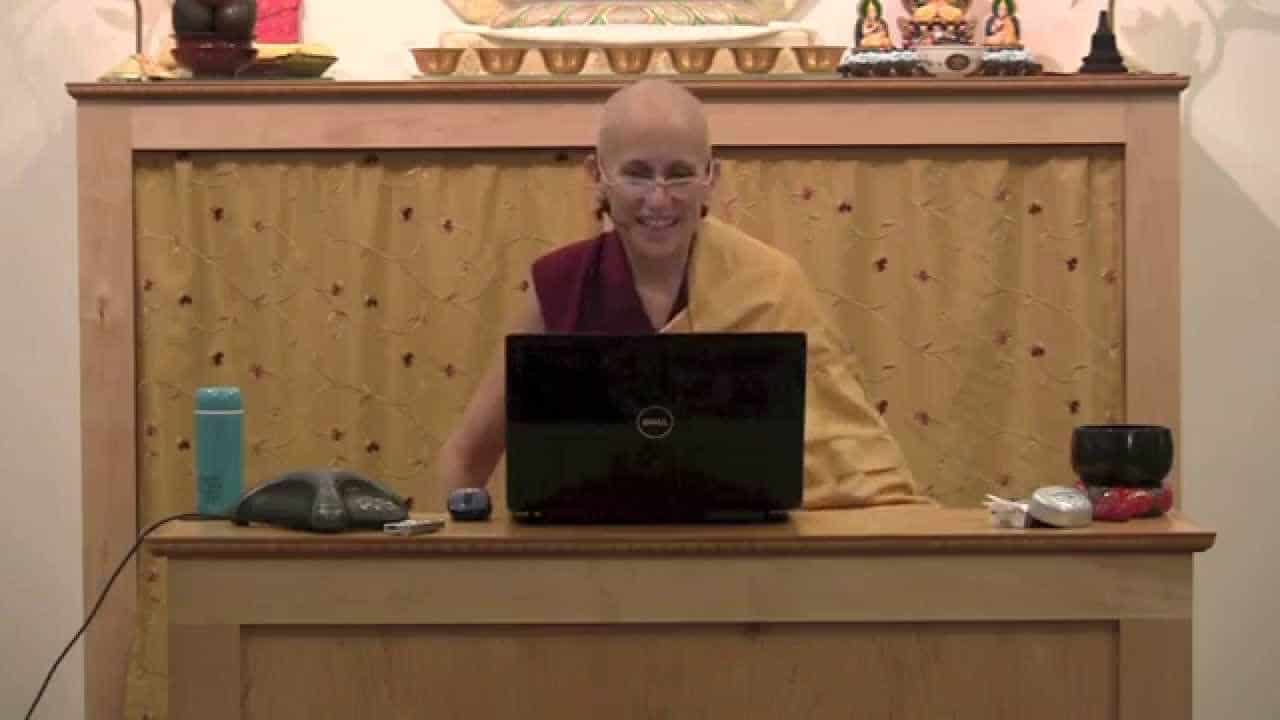

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.