Overcoming the five hindrances to concentration

Overcoming the five hindrances to concentration

Part of a series of teachings on The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, a lamrim text by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the first Panchen Lama.

- The five hindrances to developing concentration and the antidotes that aid in overcoming them

- The relationship between ethical conduct and concentration

- The eightfold noble path within the framework of the three higher trainings

- Cultivating the right way to practice each of the eight and avoid their opposite

Easy Path 32: Concentration and the eightfold noble path (download)

Good evening everybody out in all the different corners of the world. In some places it’s still Friday, some places it’s Saturday. But we’re all here together now listening to the teachings. Let’s start with our practice as we usually we do before the teachings. I’m counting on you that you have learned the practice and are practicing it fairly often, if not daily, so that I don’t need to do a lot of guiding about it.

Begin by visualizing the Buddha in the space in front of you. Remember your entire visualization is made of light. He’s surrounded by all the other holy beings, Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and so on. We’re surrounded by all the sentient beings. I think today it’s especially good if we put all the people involved in the chaos in France in our visualization. The people killed, the people perpetrating the killing—that we put all of them in front of us and think that we’re all facing the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha together: All seeking refuge, all seeking a path out of our confusion and misery. We imagine leading all the sentient beings in doing the following recitations and generating all the feelings and thoughts the recitations express.

[Preliminary Prayers]

The fact that I and all other sentient beings have been born in samsara and are endlessly subjected to various kinds of intense dukkha is due to our failure to cultivate the three higher trainings correctly once we have developed the aspiration for liberation. Guru-Buddha, please inspire me and all sentient beings so that we may cultivate the three higher trainings correctly once we have developed the aspiration to liberation.

In response to your requesting the Guru-Buddha, five-colored light and nectar stream from all parts of his body into you through the crown of your head. Similarly, this is happening with all of the sentient beings around you and the Buddhas on their heads. The light and nectar absorbs into your mind and body and those of all sentient beings—purifying all negativities and obscurations accumulated since beginningless time. And especially purifying all illness, interferences, negativities and obscurations that interfere with cultivating the three higher trainings correctly once you have developed the aspiration for liberation. Your body becomes translucent, the nature of light. All your good qualities, lifespan, merit, understanding of the Dharma and so forth all expand and increase. Having developed the aspiration to liberation, think that a superior realization of correct cultivation of the three higher trainings has arisen in your mindstream and in the mindstreams of others.

Imagine what it would feel like inside of you to have that very strong aspiration for liberation, and then to be correctly cultivating ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. What would that be like? Imagine feeling that.

The four noble truths

We’re on the section of the lamrim that is for people of the middle capacity, or it’s in common with people of the middle capacity. In other words, people who are meditating on the four truths seen by the āryas [the four noble truths] and have a strong renunciation of the first two truths (true duḥkha and true origins) and have a strong aspiration to cultivate the last two truths (true cessations and truth paths).

When the Buddha was talking about the four noble truths he talked about the way we’re supposed to relate to each one of them. True dukkha, all the unsatisfactory conditions, they’re to be known, they’re to be understood. True origin, or true causes, they’re to be abandoned. True cessations are to be actualized. True paths are to be cultivated. For each of the four truths there’s a specific way that we want to relate to it so we have to make sure that we’re relating to it in the proper way.

We pretty well covered the first two in a lot of depth—well, not so much depth but some depth before. We’re mostly focusing on the last two now, especially truth paths. True paths include the three higher trainings because we’re talking about the person practicing in common with the middle capacity being. The three trainings are ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. Did I talk about the different kinds of ethical conduct, the different kinds of prātimokṣa precepts before? I talked about the eight kinds of prātimokṣa precepts and then the four factors that lead us to break them, and the four factors leading us to keep them. If you don’t remember it means you didn’t review your notes, right? We did those four because they go together—the way to keep them and the way to break them go together.

The five hindrances to concentration

I thought today we’d talk a little bit about concentration. Of course, there’s a lot to say about concentration. I say this because we have to start with choosing a suitable object of meditation upon which to develop concentration. That’s going to differ for different people. Very often the general ones that are prescribed are meditation on the breath or meditation on the visualized image of the Buddha. Those are the ones that are generally prescribed. Sometimes in conjunction with your teacher you may feel that another one is more suitable for you and your kind of character.

The first thing we have to do in developing concentration is—because our mind is all over the place, isn’t it? We sit down and we think about everything under the sun except our object of meditation. There are different ways to talk about the hindrances, the interfering factors to concentration. Today I thought I’d talk about—since we’re talking about the middle scope, middle capacity person—the hindrances as they’re described in the Pāli tradition. I’m sure you’ll resonate with these because they’re in our mind all the time. I’ll list them and then we’ll talk a little bit about them.

The first one is sensual desire. Second one is malice. Third is dullness and drowsiness. Fourth is restlessness and regret. Fifth is deluded doubt.

-

The first hindrance: Sensual desire

The first one, sensual desire, this is first because I daresay that most of our distractions go in this direction. We want pleasure, don’t we? It’s called sensual desire because it’s mostly through objects of our senses. We want to see beautiful things, hear beautiful sounds, smell nice smells, taste nice tastes, and to have nice tactile sensations. Even if we look at things like approval and reputation, in one way we can say well they aren’t sensory. It isn’t sensual desire. But it kind of is because how do we get approval or a good reputation? It’s through hearing pleasant sounds or reading nice words, isn’t it? So it’s again coming back to our senses and things that we can get from outside for us sense addicts. That’s why it’s said we live in the desire realm. It’s because we’re totally hooked on desirable objects of the senses. We’re so hooked on them that when the Buddha even suggests that we’re addicted to them and that we might be happier not being so hooked on them, we get really upset. “What’s wrong with sense objects? The sensual world is beautiful! It’s stimulating. Science is investigating it so we can understand it better. What’s wrong with this?” It’s the way we usually respond.

Well, there’s nothing wrong with sense objects. They are what they are. But the fact of the matter is that when we pay a lot of attention to them—especially with attachment—we get more and more confused in our lives. This is because our mind just gets totally overcome with this desire to have good sensory experiences and avoid unpleasant ones. We really are addicts because if you watch: Every day, every little minuscule effort we make is usually based on, “How can I get the most pleasure?” What particular foods am I going to put on my fork in this bite?” It’s all based on how I can get the most pleasure. “What am I going to do first thing this morning?” is based on getting pleasure.

Since during our regular lives we’re so hooked on this, when we sit down to meditate what is it that comes so strongly in our mind? Daydreams about sense pleasure. We’re sitting there in perfect meditation position. Maybe you got through two breaths then lunch appears in your mind: “I wonder what we’re having for lunch. I wonder what we’re having for snack time. Oh, we took precepts today. Well, there’s always a beverage. I wonder what beverage I can have.” Then your mind goes off to think of your boyfriend, your girlfriend, your husband or wife. It goes off to think of all the places you’ve traveled to in the past and where you where you want to travel to in the future. You start thinking about your possessions, maybe your jewelry, your clothes, your sports equipment, your tools, your paints, your musical instruments, your bowling shoes, your dancing shoes, or whatever it is. Our mind starts going to our possessions. It starts going to our money because we need money to buy possessions: “What was my income this month? What am I going to spend it on? What stores can I go to to buy this? Where can I get the best deal? How can I get something nicer than what my friend has without looking like I’m competing with them?” We get very distracted by sense objects, don’t we?

We can even sit there in our meditation session and, this one’s really deceptive, “Oh, I want to get a new Buddha for my altar! Oh, this Buddha statue’s so beautiful. It’s made out of marble. It’s carved so perfectly well.” Really, like that, we go on and on. We go off daydreaming about our Buddha statue. Of course, there’s the pedestal we’re going to put it on, or the cloth we’re going to make to set it on, how beautiful our altar’s going to be. What a gorgeous thangka we’re going to get. We think that’s Dharma practice because the objects of distraction are altar objects. What kind of mala can I get? I saw one of those malas that kind of sparkles in the dark. Have you seen one? One of our venerables had one. I saw it when we were in India. I saw it sparkling in the dark. Wow, it was really pretty. It was green. She didn’t give it to me. [laughter] Wow, I wonder how I can talk her into giving it to me. But it doesn’t look too good for me to have a sparkling green mala, does it? That would ruin my reputation. She’d better keep it. I’ll take the dull wooden one—that way I’ll look like a renunciate. [laughter]

All of this happens in a meditation session, doesn’t it? Or you sit there—you’re going to take your anagarika precepts. What color blue should my anagarika clothes be? Should they be really baggy? Should they be snug fitting? What kind of fabric? Oh, there’s this really nice smooth fabric I like so much. I bet you they’ll get me the rough, ugly fabric. But if somebody offers me some nice, beautiful, smooth fabric, then I can’t refuse it. How can I get some of it?

Attachment to sense objects—what’s the antidote to this? You contemplate death and impermanence; you think of the disadvantages of cyclic existence. If you contemplate death and impermanence you realize the object you’re craving is changing and impermanent; and that you too are changing and impermanent. At the time you die all these sense objects are really not going to matter very much. You think about the disadvantages of cyclic existence and the kind of karma that you create by obsessing and being addicted to sense objects. That helps calm your mind down so that then you can focus on your chosen object of meditation. Remember this, all of you who are starting retreat next week.

-

The second hindrance: Malice

Then the second hindrance is malice or ill will. Sensual desire is, “I want.” Malice and ill will is, “I don’t like!” It’s like rowing: I want. Get away from me. I want. Get away. Sensual attachment, malice and ill will. Malice and ill will arise for everything we don’t like, everything that is interfering with our happiness, right? When there’s something we don’t like, do we just sit there and go, “Oh. Here’s this thing interfering with my happiness. It’ll go away soon.” Do we think like that? No. Here is this thing interfering with my happiness—this is illegal! It is a national catastrophe! It is unallowable! I’ve got to do something about it immediately otherwise I will experience great suffering. So we sit in our meditation looking so sweet—and contemplate how to get even with the person who’s getting in our way. Thought arise like: How to hurt the feelings of somebody who hurt our feelings; how to ruin the reputation of our competitor; how to deprive the person we’re jealous of of what they have, even if we don’t get it.

We can spend a long time on malice and ill will in our meditation sessions. I remember the retreat I did after I left Italy and after I left Sam. That whole retreat, mostly, was about malice and ill will—working on them and trying to calm down a little bit. Get myself calm during the session. Stand up at the break and “Ahhh!” again. Basically the whole retreat I was so angry. Clearly malice and ill will are going to take us away from our meditation object. Not only are we going to create a lot of negative karma under their influence, but we’re totally distracted from our meditation. All we can do is sit there and think about who we don’t like, and how unfair it is, and what we’re going to do to be victorious in this situation. We can spend a whole meditation session on it. “I take refuge until I am …. my brother, oh, he’s driving me crazy—and my sister, and my friends, and my pet frog. Oh, I just, all the time, people, oh, I’m so mad. I’m so angry, I’m so mad. I’m so angry [counting mala]. I’m so mad, I’m so angry.” [bell rings] [laughter] “Oh, I dedicate the …. um, I don’t really have anything to dedicate this session.” [laughter] We’ve all done that, haven’t we? I’ve done that. What do we meditate on to overcome our malice and ill will? Meditate on loving-kindness, fortitude, and the disadvantages of anger and joy. Yes, an antidote to jealousy—that could work. How about forgiveness? Wouldn’t forgiveness be a good thing to meditate on when we’re having a lot of malice? Meditate on forgiveness.

Remember these antidotes and learn them. Fortitude: How do you meditate on fortitude? How do you meditate on loving-kindness? How do you meditate on forgiveness? Then if you have one of these wonderful sessions you can do something with your mind instead of it just getting stuck in anger and rage.

-

The third hindrance: Dullness and drowsiness

The third one is dullness and drowsiness. You’ve been there—with your sādhana [mimes falling asleep]. “Let’s see, did I say the four immeasurables or not? I can’t remember because I think I fell asleep after the…. [mimes falling asleep]. “May all sentient beings…. [sleeps] have happiness.” Dullness and drowsiness: We’ve had enough sleep, sometimes more than enough sleep. Often our dullness and drowsiness have nothing to do with the amount of sleep we’ve had. They have to do with our internal resistance to the teachings. Or they have to do with negative karma from disrespecting the teachings or the teacher, or the Dharma materials in the past—that kind of karma ripening. In break time we’re wide awake and energetic. We sit down to meditate and kerplunk. Have you noticed? Often it’s this very special kind of falling asleep. It’s like you’ve been drugged, isn’t it? It’s like totally impossible to keep your eyes open. You really feel like you’ve been drugged. But we haven’t been drugged. It’s just the karma ripening and our dullness and drowsiness.

What are the antidotes to this? This is clearly a hindrance, isn’t it? You can’t meditate when you’re dull and drowsy. And if you start snoring you’re going to really disturb the people next to you. What’s the antidote? One is open your eyes. That’s why they say when you’re developing concentration to keep your eyes a little bit open. Make sure your head isn’t drooping. Make sure your back is straight and your head is level. Purification can help a lot too. Do prostrations in the break time. If you’re having trouble staying awake during sessions come into the hall a few minutes early and do prostrations. Do the 35 Buddhas practice. Or splash your face with some cold water. Take off the two dozen blankets you have covering you. If you’re a little bit cold, you’ll stay awake better. Don’t make the hall too warm. Of course, I say that and then they make it freezing temperature. Then I say don’t make it too cold and they make it 80 degrees—extremists. But try. And if you’re a little bit cooler than you’re used to being, it will help you stay awake.

Get some exercise in the break time. Look long distances. That’s really important. Go out on the balcony, look at the sky and the stars, and look at the mountains in Idaho. Stretch your mind. It’s very good. Make the meditation object you have chosen very bright. Meditate on precious human life—things that make the mind more joyful: refuge, Buddha nature, precious human life, things that uplift the mind. If you’re doing the breathing meditation imagine exhaling all your drowsiness and dullness in the form of smoke that dissipates as soon as it leaves. Then when you inhale imagine inhaling light that completely fills your body and mind. Or imagine a very bright light at the tip of your nose. Or imagine the Buddha on your head and light coming from the Buddha into you. Those are all very very good for helping with drowsiness and dullness.

-

The fourth hindrance: Restlessness and regret

Then the fourth one is restlessness and regret. They come together as a pair because there is some kind of similarity with them. Restlessness is, well, we all know what restlessness is. You can’t sit still and your mind can’t stay still. You should be doing something other than what you’re doing and you’ve got the heebie jeebies. You’re restless. Or even your body isn’t restless, your mind is restless: “What am I going to concentrate on, what am I going to meditate on? I don’t want to. I don’t feel like doing that, ahh.”

And then regret is—here it’s a negative kind of regret. Let’s describe it a little differently. It is a negative kind of regret; but it’s a feeling that you should have done something you didn’t do, or you shouldn’t have done something you did do. It’s this uneasiness, this restlessness, uneasiness, regret: “Oh, what did I do, I shouldn’t have done that. They told me to wash the dishes this way so the health department didn’t bust us, and I didn’t do it right. I’ll have to go back and wash those forks again in the break time and hope that they didn’t notice that I didn’t wash the forks correctly. But I really, I regret that.” You get hooked into this thing.

Or it could be just all sorts of regrets. You think back about your life and instead of regretting in a wholesome way and purifying and making amends, the mind just is, “Oh, look what I did. This is really awful. I shouldn’t have done that; and I should have done this. I could have come to the Abbey a month earlier but I didn’t. I didn’t feel like it—but I should’ve felt like it. I regret that I didn’t come, but actually I don’t regret it. But I do—kind of. And then I’m going to leave and then after I leave the Abbey, “Oh, that’ll be good for then I can go to Starbucks. But when I get home I’m sure I’ll regret having left the Abbey and I’ll want to be back here. I regret thinking about leaving the Abbey and regretting it after I left.” But there’s no regret for going to Starbucks. [laughter]

All this kind of regret, what’s it like? It’s not a good kind of regret where you really are doing a life inventory and you see your mistakes. You have honest regret and you want to fix, make amends, and purify. It’s not like that. It’s this kind of guilt, remorse, “I should have; I shouldn’t have,” kind of regret.

And restlessness—what’s the antidote to that? Breathing meditation because your mind’s full of garbage, isn’t it?

[In response to audience] You’re saying breathing meditation doesn’t work for you but meditation on the nature of our body works. That’s valid enough. Yes, it can work very well because when you really sit there and you visually dissect this body, it’s very sobering. It’s very sobering. It kind of stops that restlessness and also helps us focus on what’s important—like, “I’m stuck with this body and look what it is. I’m going to get another one just like it if I’m not careful.”

[In response to audience] So if you’re having this kind of confused regret it can be very helpful to sit and think, “Well, who’s responsible for what in this?” I say this because often we tend to take responsibility for things that aren’t our responsibility, and we don’t take responsibility for things that are. It can be very helpful—especially when we start this kind of thing like, “Well, I said this and it made this person unhappy. I’m to blame for their unhappiness. I regret it. But I’m actually angry at them because why should I have to monitor myself simply because they don’t like what I’m doing? But I do regret that they’re unhappy; but I regret that I’m unhappy.” All this kind of stuff, to really sit down and think about it: What am I actually responsible for? If somebody else is unhappy, to what degree am I responsible for it?

[In response to audience] You’re saying look at the situation and question, “Was I lacking in integrity and consideration for others in that situation?” In which case, “Yes, it is good for me to have regret.” You make it into the wholesome regret. Or maybe it’s a situation of, “I did have integrity and consideration for others, in which case I don’t need to be so confused.”

Audience: It seems like with both regret and restlessness there’s a dissatisfaction.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, there’s an uneasiness in the mind.

Audience: It seems like sometimes when I’m trying to meditate my mind is wandering off and I try to be content to just follow my breath and develop contentment.

VTC: So it could be a thing of developing contentment. Often it’s the attachment to sensual pleasure that is behind the feelings of discontent and dissatisfaction, but restlessness can certainly join in there.

[In response to audience] You’re saying that if you’re confused about the regret, one thing that’s usually behind it is you’re attached to approval so you’re not sure: “Well, am I responsible about that, or aren’t I? Are these people going to blame me or aren’t they going to blame me? Because I don’t know whether what I did is good or bad, I’m waiting to see what other people think about it and then I’ll figure it out from there.” And then we get very confused, don’t we? “Do they approve? Do they not approve? They approve, but actually it wasn’t so good what I did. They shouldn’t approve, but I want them to approve. And if they approve, then maybe actually it wasn’t so bad what I did. But I still don’t feel completely at peace with it.” And on and on it goes.

This regret and restlessness, sometimes can you feel in your mind this certain kind of uneasiness and you’re not sure about what? That comes in this kind of category. You’re uneasy, you feel like something’s not right, but you don’t exactly know what it is. So in those situations I often stop and say, “Okay, when did this feeling begin? And what was I doing in the hour before that feeling arose? Was there something that set me off that I was unaware of at the time?”

-

The fifth hindrance: Deluded doubt

The fifth hindrance is deluded doubt. This is doubt. We covered this one before when we talked about the six root afflictions. This is doubt here, like “Is it possible to develop concentration or is it impossible? Does this method work or doesn’t it work? Do I have the right meditation object? Maybe I should switch my meditation object. Actually, I think I have more than six hindrances—five hindrances. I think I have six but they say five. But maybe I can include them one in the other. I don’t know. But does this whole thing work? Do these antidotes really work? How many times do I have to do these antidotes before they work? I don’t know. I tried them once and nothing really happened so I don’t know. So should I continue or not? Can I develop samādhi [concentration] this retreat? Should I continue doing śamatha [serenity, calm abiding] meditation? Maybe I should switch and do lamrim instead. No, maybe I should go out and actually offer service in society. That might be the best thing. Well, yes, I could do that, but you know they always say study is very good; so maybe I should go study. So let’s see, I’m in retreat: Maybe I should study. Maybe I should go do some social service.” But when I’m out doing social service, then I think “Meditation’s the best thing to do. So now I have the opportunity to meditate I should really meditate. But I don’t know; I just don’t know if this method works. They say that thousands of yogis have attained śamatha by using it but they already had śamatha before, they weren’t like me.”

What do we do with doubt? What’s the antidote to doubt?

Audience: Study.

VTC: Are you sure? [laughter] Study helps but is study the antidote? Maybe there’s another antidote that’s going to work better than studying. What else do you think could be the antidote?

Audience: You’re going to have to work with your emotional doubt.

VTC: What do you mean by emotional doubt?

Audience: Sometimes I think we doubt the methods. But maybe sometimes there’s a lot of emotion around that and you have to work with the emotions that come up around it. And maybe self-doubt is more….

VTC: Sometimes it’s self-doubt: “Oh, everybody else can do this method, but I’m just not up for it. I’m sure it’s not going to work for me, because nothing ever works for me. Everything I try…. I went to Maharishi Yogi. I did that—didn’t develop samādhi. I meditated on crystals—didn’t develop samādhi. I did Reiki—that didn’t work either. I did Christian centering meditation—no samādhi. I went to Theravada monastery—no samādhi. Went to Zen—no samādhi. Went to Tibetan—no samādhi. [sigh] Where am I going to get samādhi? Why haven’t they developed a pill for it?” [laughter] “That’s what I’ll do! I’ll go become a scientist and develop the samādhi pill! My doubts are over!”

We can get a lot of emotional doubt involved with things like self-esteem, capacity, and inclusion or exclusion. There are lots of ways that doubt works. They’re all like sewing with a two-pointed needle. You can’t get anywhere with a two-pointed needle. So study is very good as an antidote. When it’s just this restless kind of doubt watching the breath is also very good. I find, too, going back to what in the Dharma really touched my heart and that I know without a doubt is true. Go back to that—because we each have something like that in our mind. We heard a certain teaching and there was no way our afflicted mind could get around that one. If you go back to that it can really help the mind to settle. You have the certainty of, “This is what I know is true.” Then you build from there—from what you know is true.

[In response to audience] If you have a very strong relationship with your spiritual mentor and a lot of faith in your spiritual mentor, doing guru yoga can be helpful. It’s like this practice we just did with imagining the Buddha on our head and the light coming from the Buddha into us purifying. That can also work to help us calm our doubts and get us centered and just think, “I’m purifying all of that kind of conceptual rubbish.”

Let’s pause here. Any questions so far?

Audience: Not so much a question, or maybe there’s a question in it. It’s about this deluded doubt. I was thinking of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s reasoned faith, faith based on reason. So when I get stuck there, it’s a lot with the two-pointed needle. I can go to, “Okay, it’s kind of trust. Like, who do I trust?” Then my teachers come to mind; and then I saw, “Well, what do they say that they did to be how they are?” I think that’s faith based on reason. I’m reasoning it out, but there is some kind of faith aspect in that.

VTC: It’s kind of similar to what Rebecca was talking about. You have a strong relationship with your teacher. You have a deep trust in what your teacher has taught you and what your teacher has practiced themselves. So when you think of your teacher and you think of their qualities, then you think, “Well, basically they’re telling me how they became the way they are. They’ve practiced these teachings and gotten the result. And I look at them and they’re trustworthy people so I can trust the method that they’re teaching me.”

Audience: Even if I don’t get it myself right now.

VTC: Yes, even if it’s not totally apparent to me right now how the whole thing works. It’s like, “I know that they are reputable people that would not mislead me. I can see their good qualities and they must have cultivated something to get them. They’re telling me what they cultivated so I can trust them and I can trust what they’re telling me to do.”

This is a very good way to get out of the ditch because the doubt just throws up everything. Doubt is kind of like a whirlwind of confetti. Finding your way, something that you want to anchor yourself to—whether it’s what you know in the Dharma that you can’t refute, whether it’s trusting your teacher, whether it’s studying the particular topic. But anchoring yourself to something is going to help you calm that mind. I think also it’s important to recognize doubt for what it is. Otherwise doubt comes up and we don’t recognize it as doubt. We think it’s legitimate questions—and then we think about them and we get more and more confused.

Audience: I’m puzzling whether this is really true. But at least the way doubt works for me. It’s usually discouragement—which I now recognize is a habit of mind. So it’s easier just to go [claps], “Stop!” To recognize it for what it is as something that’s trying to harm. That seems effective.

VTC: You’re saying what works for you is when you see the doubt coming up, to recognize it for what it is: this is doubt, this is useless, stop! Drop it. Quit. And just be very decisive in that way.

Audience: But haven’t you already figured out that it’s a dead end in order to do that?

Audience: Yes, I suppose.

VTC: Yes. I mean, you’ve looked at the doubt enough and you’ve seen that it’s not taking you anywhere so you have some confidence in that.

Audience: There’s a question online. Can you speak about how the practice of ethical conduct supports the development of concentration, and vice versa.

VTC: How does the practice of ethical conduct supports concentration, and vice versa? Well, one way is if you don’t keep ethical conduct then you have a lot of confusion going on in your mind about how I wasn’t completely ethical, but I need to keep up the appearance of being ethical so how am I going to do that?” So that becomes a hindrance to concentration, doesn’t it? It’s because you’re thinking of how to keep on looking ethical, although you aren’t—because you’re attached to your reputation. Or if you don’t keep good ethical conduct then it’s, “Well, I did this but I shouldn’t have,” and then justify, rationalize, deny. All those psychological mechanisms come up as a way to try and deal with our feelings about our unethical conduct. That also becomes a big distraction in trying to develop concentration. Good ethical conduct completely cuts out all that kind of doubt and bewilderment—all of that kind of stuff.

Also, there are two mental factors that are important both in ethical conduct and with developing concentration. They’re mindfulness and introspective awareness. Mindfulness, in terms of ethical conduct, keeps us focused on our precepts, on our values so we know what we want to do, how we want to behave. Mindfulness is a mental factor that focuses on something worthwhile and has the power to keep our mind there without letting the mind get distracted to other things. It works in our day to day life. Then as we build up that mindfulness in our ethical conduct, when we sit down to meditate we have that ability to keep our mind on something. That works very well for keeping our mind focused on the object of meditation.

The other mental factor, introspective awareness during our daily life, in the practice of ethical conduct, this is the one that checks up and says, “What am I doing? Am I acting according to my precepts? I set my mindfulness to do this in this way. Am I doing that or am I off-track?” Introspective awareness functions that way in developing ethical conduct. As we develop it there, then when we start doing concentration we have that ability to monitor the mind. Then in the practice of concentration it’s, “Am I on the object of concentration or has one of the hindrances arisen?” Ethical conduct is a very necessary prerequisite for developing concentration. First ethical conduct helps us to develop mindfulness and introspective awareness. Second of all to get our ethical conduct intact so that we don’t have so much confusion in our mind—and regret, remorse, doubt, rationalization, attachment to reputation, self-hatred. All those things that come distract us when we’re trying to develop concentration. But they arise because we haven’t kept good ethical conduct.

Ethical conduct is the basis for developing concentration. Of course the more you learn to concentrate, the more you’re going to care about your ethical conduct too. It usually goes from ethical conduct to concentration. But it can also go from concentration to reinforcing your determination to have good ethical conduct. This is one step that many people try to skip—

especially in the West. It’s like, “Ethical conduct? That’s Sunday school stuff. That’s ‘don’t do this, and don’t do that,’ and all it does is make me feel guilty. Anyway, I want to be free!” This is something that many people really have to work with at the beginning—even developing respect for ethical conduct. They learn to get over a lot of the preconceptions about, “Oh, this is goody two shoes. This is Sunday school. This is, ‘you can’t do this and you can’t do that.’ This is somebody out on the outside bossing me around and telling me what I can do and can’t do.” Many times, depending upon how you grew up, you really have to do a lot of work just to get your mind to see the value of ethical conduct in a correct way. Are there other questions?

Then I wanted to go on and also to talk a little bit about, since we’re talking about true path, then we had ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. So next we’ll talk about the noble eightfold path. This is often described as—especially in the Pāli system—as what is the path. What are true paths is the noble eightfold path. I don’t know if we’ll get through all of it this session. We’ll see how far we get.

Eightfold noble path

There are eight of them clearly—and these eight can be included within the three higher trainings. It starts out with right view and right intention; and those are included in the higher training of wisdom. Then it goes to right speech, right action, right livelihood; and those three are included in the higher training in ethical conduct. Then right effort—which applies to all three higher trainings. Then right mindfulness and right concentration—which apply to the higher training in concentration. So we’ll talk about those very briefly.

-

Right view

Usually at the beginning of the practice we start out with right view. Here, in particular, right view means: understanding karma, understanding that our actions have an ethical dimension, that there are past and future lives, that afflictions cause us suffering, that they can be eliminated. It’s kind of the Buddhist worldview to some degree or another. We have to start out with that so that our practice is actually one that becomes Buddhist. I say this because if we don’t have the Buddhist worldview, if we don’t have refuge in the Three Jewels, then we can keep good ethical conduct or we can meditate with mindfulness and concentration—but it won’t necessarily lead us to Buddhist realizations. I remember reading the book of one person who wasn’t sure what they believed. They did Zen meditation and realized they believed in God. If you’re really doing Zen meditation as a Buddhist meditation, your conclusion is not that you believe in God.

-

Right intention

Right intention is the next one. Wrong intention, let’s start with wrong intention. Well, if we go back to views. Wrong views: instead of correct view, it’s wrong view—so not believing in past and future lives, not believing in karma, not believing that it’s possible to eliminate afflictions, and so on. Then wrong intentions are like having a lot of desire, malice, and cruelty. Those are wrong intentions for doing things, aren’t they?

Right intention becomes benevolence, renunciation, and compassion. Benevolence is a kindly feeling, a feeling of goodwill towards others. Renunciation is the wish to be free of cyclic existence or the wish not to be so attached to sense objects. And then there’s compassion. The benevolence counteracts the malice, the renunciation counteracts the attachment and desire, and compassion counteracts cruelty. Cruelty is hiṃsā, violence; and compassion is non-cruelty, ahiṃsā —what Gandhi-ji [Mahatma Gandhi] taught.

We start out with the right view and the right intention. That’s a really good foundation. We have the view so we know why we’re doing it; and we have a good intention. We’re not studying the Dharma and practicing the path to make money. We’re not doing it to please somebody. We’re not doing it for fame and reputation. We’re not doing it out of boredom. We’re not doing it to compete with somebody else. We’re doing it with a spirit of renunciation, of benevolence, of compassion—and especially if you’re following the Mahayana path—with bodhicitta as well. With that perspective, with our view and our intention intact, then we start on the three branches that fall into ethical conduct.

-

Right speech

Wrong speech is the four nonvirtues of speech: lying, creating disharmony, harsh words, and idle talk. Right speech is the opposite: speaking truthfully, speaking to bring about harmony, speaking with kindness, and then speaking at appropriate times and of appropriate topics.

It’s not so easy to have correct speech. It’s not so easy. This is one of the reasons why in the retreat we really cut back on the amount of talking we do. It’s a way to cut back on the nonvirtues of speech, and a way to look at our tendencies to talk. You keep finding that you are on the verge of saying something and then you have to stop because you remember that we’re keeping silence. Then you stop and say, “Well, what was I about to say? Why did I want to say that? What good was it going to do?” That can be very helpful to us.In keeping silence in the retreat that doesn’t mean that we become the author of a whole notebook full of notes. I remember at Cloud Mountain when we had retreats there, there was a bulletin board where everybody put their notes. Every break time everybody headed for the bulletin board: “Is there a note for me?” And if there wasn’t, or even if there was, they would write a note and pin it on the board: “I really liked the way you rang the bell after meditation, it was so helpful.” Pin it on the board; then they’ve got to respond. Somebody writes me a note, that means I exist. I’m getting some attention. The more notes I write, the more responses I get. The more I’m sure I exist. It’s amazing, isn’t it? So we try not to do that during retreat.

-

Right action

Wrong action is the three physical nonvirtues: taking life or harming others physically, stealing their property, and then unwise or unkind sexual conduct. Then the three that constitute right action are saving life, protecting others’ property, and using sexuality wisely and kindly. We’ve been through all of that before. I’m not going to go into a lot of that now.

-

Right livelihood

This is how we get the requisites for life—how we get food, clothing, shelter, and medicine. How does our livelihood work? For laypeople wrong livelihood would be lying in your work or cheating people in some way. It would include making munitions or polluting chemicals, insecticides, armaments, anything. Working in the Keystone Pipeline and not cleaning up your ecological mess. Taking bribes. All this kind of thing would be wrong livelihood.

Right livelihood is working in an honest way and in a sincere way: Charging fair prices; paying your employees a fair amount; and also working in either a profession that’s neutral or one where you are benefitting others and you have the correct motivation for being of benefit to them. You want to be a doctor not because it pays a lot but because you really want to help people be healthy.

For monastics right livelihood is different. It means receiving offerings that are given to you without the five wrong livelihoods. So five wrong livelihoods: It’s interesting because these are often things that we were taught in our families to do in order to get stuff. Then we learn in Buddhism they’re considered wrong livelihoods.

-

1. Hinting: Weren’t you taught to hint for what you wanted? It’s not polite to say, “Give me this.” So you hint. “Gee, I could really use that, that’s so nice, that’s so helpful.” Hint hint hint hint. That’s wrong livelihood.

-

2. Flattery: “Oh, this person that gave me X, Y, and Z, they were so kind. It was just wonderful and they were so helpful.” Come on, you want some flattery, give me what I want.

-

3. Giving a small gift to get a big gift: Some people call this bribery—though we don’t really think of ourselves as bribing other people. That said, bribery certainly is a wrong livelihood. But we will give a small gift in order to get a big one in return. So we give a gift not because we sincerely want to give, but because, “Well, if I give them that, then they’ll like me and they’ll give me something back.” Or, “If I give them this they’ll feel obliged, and they’ll give me something nicer back.” So, again, wrong livelihood. It’s a lack of sincerity.

-

4. Coercion: Most of us, again, we don’t like to use the word ‘coercion’ because we don’t think of ourselves as coercing people. Another way to express it is you put people in a situation where they can’t say no. So, “All these other people donated a hundred dollars; so and so donated a hundred dollars. What is your pledge? How much are you going to donate?” So this refers to pressuring people.

-

5. Hypocrisy: Making ourselves look good in order to impress somebody so that they’ll give us some kind of offering. For monastics these five are considered wrong livelihood because we’re supposed to live just on donations, on offerings. You can’t go around hinting for everything, and flattering people, giving them little things so they’ll give you big things, putting them in positions where they can’t say no, and then decking yourself out like some big important Dharma practitioner so that they’ll really want to give something to you because they can create a lot of merit from it.

-

Questions and answers

[In response to audience] Of course these five are unethical for lay folks as well. But in terms of wrong livelihood, for lay people the grosser kind of thing would be working in some kind of business that is harmful—or work involving cheating or lying to people. Of course these five wrong livelihoods would pertain to lay people, but it’s monastics that specialize in them. Other questions before we end?

[In response to audience] These five wrong livelihoods are very hard habits, aren’t they? And the longer you’re ordained the more subtle they become—very true.

Audience: It’s very tricky. Because of so much kindness and support, I have to be very careful about even saying, “I want” or “I need.” Even if you don’t really even have hinting at the back of your mind (although you’d better look carefully to see if you have that in the back of your mind) because people really respond. It’s very tricky.

VTC: Yes, very tricky. To really monitor, as a monastic, to monitor what do you really need. And what is the mind saying, “Oh gee, it would be nice to have…” because people are generous, and they do want to help, and it’s not right to take advantage of them.

Audience: For family businesses who are in the seafood business for a long time, to kill in order to sustain business to raise the family, what can the family do to reduce the bad karma?

VTC: So it’s a family who’s in the seafood business for quite a long time, and what can they do to reduce the bad karma that they’re creating? Best thing would be to sell the business. Or dismantle the business and do something else. The way the question is asked it sounds like that isn’t something that the person wants to do. So in that situation I would say at least have regret about killing. But it also becomes hard to have regret about killing if your livelihood and the livelihood of your family depends on it, isn’t it? And you’re doing really well. You’re making a lot of money and you need to make a lot of money. Your making money depends on killing; so it’s hard to have regret for the killing you’re doing—although regretting nonvirtue does reduce the heaviness of the karma. Do purification afterwards. But of course, if you intend to continue on in the seafood business then, of the four opponent powers, the one of having sincere regret, it’s hard to have regret. The determination not to do it again, that one’s not going to be very strong either because that’s how you earn your livelihood. So, sorry, I’m not a very big help on that one.

[In response to audience] So you worked in seafood for a while and you were dealing with animals that were already dead most of the time. You didn’t do the killing—but did you because you wanted the dead animals? Were they killed for you? Oh, you were processing them. Okay, so you weren’t catching them, you weren’t cooking them and serving them. You were just working in a factory where dead fish were being processed and put into cans or frozen. That’s not as bad as doing the killing yourself because you don’t really have the intention to harm the fish. But part of it’s going along with the supply and demand thing.

[In response to audience] That’s a very good way to do it. So whenever these discussions come up about animals you always ask yourself, “Would this be okay if this were people instead?” Yikes. I think it would be quite different, wouldn’t it?

[In response to audience] Yes that’s what they always say. If you’re going to commit a negativity—have some regret afterwards, do some purification afterwards. Dedicate your virtue for the benefit of whoever it is you harmed. That always goes to reduce or purify in some way. You can also see that there’s no regret and there’s no determination not to do it again, so that you can see that whatever purification there is, is limited.

It is good to make prayers for those beings and to dedicate our merit for them. At the same time we’re killing them. That’s hard. That’s hard but it’s better than not doing it. It’s definitely better than not doing it. So, please, in the next week, think about all of this. Remember the five hindrances and try and counteract them. And then remember we went through five of the noble eightfold path. We’ll continue with that next week.

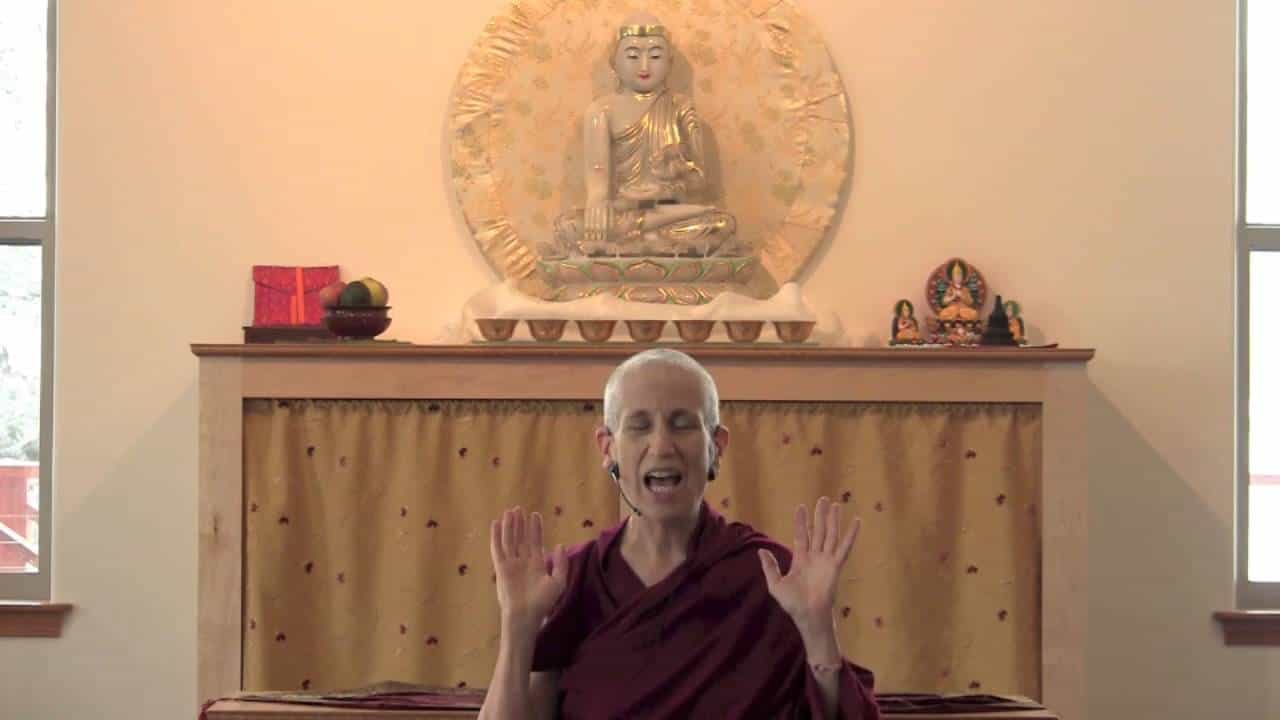

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.