Verse 52: The antidote to apathy

Verse 52: The antidote to apathy

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- With apathy we don’t give ourselves a chance to realize our potential

- Joyous effort is the opposite of apathy and laziness

- Meditating on precious human life daily keeps us from taking our good situation for granted

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 52 (download)

“What is it that makes one lose everything one ever wanted?”

Audience: Renunciation [laughter]

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Wrong answer

What is it that makes one lose everything one ever wanted?

Dissipating apathy that fails to persist in any task.

Dissipating apathy that fails to persist in any task…. So, I think I’m done with the talk now. You guys can just figure it out by yourselves, I don’t care. [laughter]

Dissipating apathy—we just don’t care. And so it’s interesting because it says, “What is it that makes one lose everything one ever wanted?” Why does apathy make us lose whatever we ever wanted? Because to get what we wanted—in a worldly way or especially in a Dharma way—we have to exert effort. We have to exert energy. Apathy is the opposite of exerting energy. Apathy is a kind of laziness. And in particular, apathy is, “Well, I just don’t care. I don’t care that much. I’m not going to try.”

For example, today I wasn’t prepared for Jeffrey’s teaching. So I got in there, I didn’t even know where we were, and I’m looking over Venerable Tarpa’s shoulder, where are we, what’s he talking about? And at that point I could have just said, “I’m not prepared, I don’t know where we are, I don’t know what he’s talking about, forget it, just sit here.” But I didn’t. I said to myself, “I’m not prepared, therefore I have to listen especially attentively and take really good notes, because I’m not likely to understand what he says because I didn’t read ahead.” So I took more notes than usual and tried to pay better attention because I wasn’t prepared. Instead of just saying, “I don’t know what he’s talking about so forget it.”

But we often do that with apathy, don’t we? We don’t give ourselves a chance to actualize our own dreams and our own wishes. We just say, “I can’t do it, it’s too hard, I’m too stupid, I don’t understand, it doesn’t matter anyway, so I’m just going to sit here.” And that’s what we do, isn’t it?

We become our own worst enemy with that apathetic mind state. We’re shooting ourselves in the foot all the time. Because we have the potential, we have the power to do something, but we don’t do it. Instead we tell ourselves we can’t. And then we just sit and feel sorry for ourselves and sulk and complain that the world’s unfair. And then wonder why we’re so unhappy.

True or not true? It’s interesting, isn’t it, how that kind of apathy really leads to a lot of unhappiness. It becomes very, very self-defeating. Having joyous effort is the opposite of this apathy and laziness, and so it’s really important that we have joyous effort.

There are four steps to joyous effort. Joy, aspiration, mindfulness, and pliancy.

-

Joy: To have a positive outlook on things. So to generate joy, to help us overcome our apathy, then we think about everything we have going for us in our lives. We think about having a precious human life. We think about the qualities of Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. We contemplate Buddha nature. We look around us and see the amazing good conditions that we have and feel really, really joyful about it.

And I think this kind of joy…. It’s really important for us to do the meditation on precious human life very regularly. Otherwise we just take everything for granted; and instead of looking at everything we have going for us we look at the one thing that’s a problem.

It’s like looking at the whole wall, from one end to the other, that’s painted one color, and you notice the tiny red dot over there and focus on that red dot. Or you have a wall made of bricks, and there are like a thousand bricks that are all in place, and you focus on the one that’s crooked. You know, it’s really very distorted, isn’t it?

The same thing with our lives. It’s important to have a joyous attitude by seeing all the good conditions that we have going for us.

-

Second, to generate aspiration. And we generate aspiration by seeing the benefit of the particular project that we’re engaged in. Like, “If I try in my meditation, my mind might actually become calmer, or I might actually understand the teachings better, or I might actually be able to put them into practice in my life.” And so you see the benefits of something and that helps you have the aspiration to do it.

-

Third, for mindfulness, to cultivate mindfulness, we practice remembering what we want our body, speech, and mind to do. And by remembering that then we set our minds in that direction.

-

Then fourth is pliancy. Or it’s a kind of mental and physical flexibility that we have at present that’s small but gets cultivated when we do concentration-style meditation, so that both the body and the mind become quite flexible.

Maybe we should also start out with some yoga, that might help, too. This isn’t written in the teachings, but you know, if your body’s giving you problems, rather than saying, “My body’s giving me problems, I can’t meditate, I can’t do this, I can’t do that,” you know? Do some yoga, take some medicine, take a walk, stretch…. Do something instead of becoming lazy and apathetic. Because when you look at it, laziness and apathy…. We have all these dreams, we have all these aspirations, but we can’t act on anything. And so again, we become self-limiting. We limit ourselves, when we have this incredible potential.

So, practice cultivating joy, aspiration, mindfulness, and pliancy or flexibility.

Epecially the joy. Think of everything good you have going for you. Think of the benefits of doing whatever project it is. Because if you think of the benefits of doing something, then even if there are difficulties you still continue on because you see the benefits.

It’s like, you go to work at a job, and you’re like, “Oh, I don’t like this job, and this is wrong, that’s wrong, ugh.” But you go to work every day because you see the benefits of it. So how come when it comes to Dharma practice we give up on ourselves? Even though Dharma practice has so many more benefits than going to work. So we need to see those benefits and see the good conditions we have, and apply ourselves with mindfulness, and learn to be flexible and pliant.

Having said that, I’m now exhausted. I don’t want to do anything for the rest of the day. [laughter]

I was just thinking that regarding apathy, sometimes we don’t even start something because we look at it and we say, “That’s too big.” And that would be like looking at our forest—240 acres, the forest really needs to be cared for—and saying, “Oh, there are 240 acres, it’s too big, let’s just forget it.” And just leave it all with all this debris and overcrowding, and who cares. But we don’t do that, do we? We do a little bit every year. And slowly it’s getting there. You can see that. I mean, just the thing of you do a little bit every year and you stay on track, and then things go forward.

[In response to audience] I think first you get discouraged and then you get apathetic. You get discouraged: “Oh, I’m incapable.” So something’s wrong with us. Or: the path is too hard. “Oh, bodhisattva path, too difficult, I can’t do that.” Or: the result is too high and unattainable. “Oh, buddhahood, hah.” And so we discourage ourselves by our own way of thinking; and then having gotten discouraged, we say, “Well, why try? Why do anything? I’ll just sit here.”

[In response to audience] It’s true, most people don’t remove their afflictions because of lack of interest. Because we don’t see the benefits of eliminating our afflictions. It’s like a person who’s sick who just gets so used to being sick that they forget the state of wellness exists and they forget what feeling well felt like so they don’t even try to get well. So we’re so used to our afflictions that we just accept them and feel defeated and don’t even try. We’re not interested. Too hard. Let science develop some pill, then I’ll take the pill.

[In response to audience] Yes, I was wondering if this one that he put in here was a different list…. But yes, steadfastness and then rest. Steadfastness is continuing on, doing what you can do as you’re able to do it without giving up. And then rest is, when you’ve completed something, give yourself a pat on the back, rest, so you can engage in the next thing full of energy. Instead of this constant push, push, push….

Sometimes in the middle of doing something you need to take a rest so you can continue with it. So you do that, but then that’s where steadfastness comes in, you’re taking a temporary rest but you steadfastly continue going in that direction.

[In response to audience] Yes, sometimes we have a hard time knowing we need to rest. Recognizing it. It’s a hard thing to be a balanced human being. Because sometimes we need to rest, and we don’t notice it, or we notice it and we refuse to do it. Other times we need to really become more active and renew our energy, but we say, “I’m too tired to do that,” and so then we don’t try. So knowing when we need to do what is a talent that requires a lot of trial and error. But it’s a really good talent to learn. How do I learn how to be a balanced person?

[In response to audience] You’re saying that part of the problem, confusion, and why people get apathetic is because they don’t know the systematic order of the teachings and how to practice them. And because they’re relying mainly on books and not on a live teacher to guide them, they read a little bit from this book, a little bit from that book, a little bit from the other book, get quite confused, don’t know what to practice first or what to practice second, don’t even know if they believe in half the things they read, and can’t understand how to put all those things together into one person’s practice.

Whereas if you study with a teacher over a period of time—not just a weekend or a week or a month, but over a period of time—and that person’s guiding you, then, you know, first you do this, and then you do this, and then you do this, and you get some kind of…. You know, that’s the beauty of the lamrim, the stages of the path.

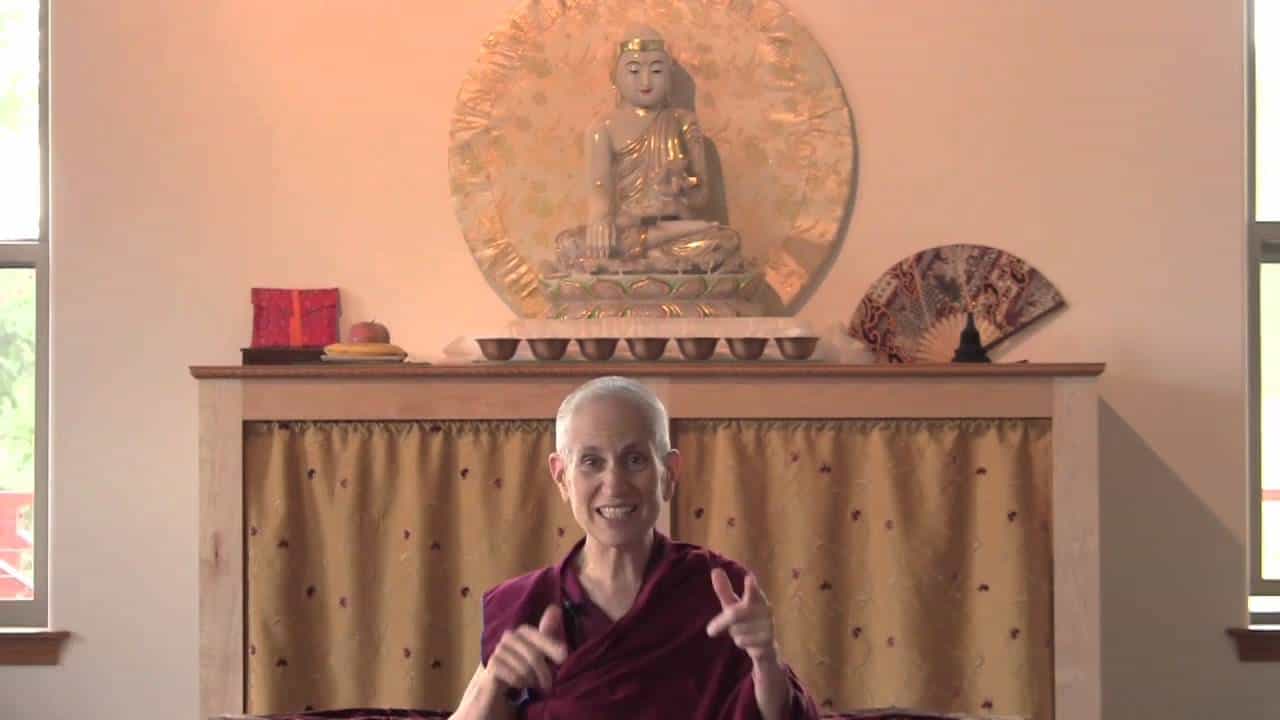

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.