Sravasti Abbey’s first kathina ceremony

Sravasti Abbey’s first kathina ceremony

- To celebrate the end of the rains retreat (varsa)

- Invitation for feedback within the sangha (pravarana)

- Kathina robe ceremony

Today is a very auspicious day and I want to thank all of you for coming. It’s a day of celebration. And in Asia, especially in Thailand, it’s become a huge festival with people lining the roads bringing robes and other things to offer to the sangha. A friend of mine even said that they have elephants in the parade coming to the temple. I told her we would forgo those. But maybe a moose would be okay. [laughter]

The kathina, the ceremony we’re doing today, happens after two other events, so I want to start at the beginning, to explain the first event, which is varsa, which is the annual retreat that the sangha does. It’s a monastic retreat and it’s usually, in Asia, done in the summer during the monsoon season, because at the time of the Buddha… If you’ve ever been in monsoon in Asia, it is raining and flooding, and this is how the rice grows. But the sangha, at the time of the Buddha, were wandering mendicants, and they went into villages to collect alms. They did not beg. Begging is when you ask people to give you something. Alms is when you’re there and then people have the choice and if they want to then they make offering. So they lived by going on alms. But in the rainy season they were trampling on the crops, they were stepping on insects. Their robes were getting washed away by the water. And it was a big mess. So the lay people criticized and said, “How come the monastics of the Buddha’s teachings are wandering around during this kind of climate when other monastics don’t.” And so the Buddha stipulated at that time that the monastics should do the “rains retreat” for the three months of the monsoon. So at the time of the Buddha usually somebody would offer a place to the sangha or to individuals and they would go there and they would stay put during that time. And they would not go into the village to collect alms. Or if they did, they would return, not stay away overnight. So they weren’t having the wandering lifestyle that they usually had at that time.

In coming to the West we changed it from a “rains retreat” to a “snows retreat.” We do it in the winter. This year it began in the middle of January and then the retreat ended last Tuesday after three complete months. At the end of the varsa there is a ceremony that’s done that’s called the pravarana, or invitation. That’s because, during the time of the retreat, harmony is really emphasized and so usually, in normal times, if somebody made a mistake in keeping their vows, or committed a fault, or something, it would be brought up and discussed, and people would remind each other and point out each other’s misdeeds. But during the varsa, to emphasize harmony, they didn’t do that.

The story of the varsa—how it came about—is rather interesting. Some monks went to see the Buddha after the varsa was over and the Buddha said, “Well, how did you live together so harmoniously?” And they said, “Well, we didn’t talk to each other.” The person who came back first from alms would set the table, eat his food, leave any remainder for the rest. The second one would come and do the same. If he needed more food he would eat what was there. The last person would come and have his meal, take any that was still remaining, and if there was some left after that, then distribute it to other people, and then clean up the dining room. And if they had to ask the help of somebody else to fill the water jugs or something, they wouldn’t speak but they would motion. And so they explained to the Buddha, that’s how we lived together so peacefully. And the Buddha said, “You foolish people. I have taught you again and again that you should discuss the Dharma together. You should learn and help each other learn.” Not just keep silent like dumb sheep. He was pretty forceful. He said, “You need to study and discuss together.”

And then the story jumps to another scene, which I’ve never seen the link between the two. But maybe somebody will. There was a group of six naughty monks and they were the ones responsible for most of our precepts. There were six naughty nuns, too, but it seems like the naughty monks did more. The monks just got the precepts from the naughty monks. The nuns, we had to get the precepts from the naughty monks and the naughty nuns.

Oh, I guess maybe the link is in the story that Buddha said we should talk to each other about the Dharma and we should admonish each other. So they (the naughty monks) started pointing out faults in virtuous bhikkshus and bhikkshunis, which is very clearly against the precept. If you make a false allegation against somebody, just because of lack of information or because you had a negative intention, you were mad at the person, they did something you didn’t like… They were alleging faults for the monastics that had pure conduct. So then the Buddha said, “Well, you can’t just do that. Before you point out other’s faults you have to ask them permission. So then the virtuous monastics went to these six naughty monastics and said, “May we point out your faults.” And they said yes, but then after the virtuous ones did, the naughty ones got really mad, and they criticized. So then the Buddha said, “Okay, during the varsa you’re not going to discuss these things, at the end of the varsa you clear everything up and then anything that is left remaining, that you handle at the pravarana ceremony.

Pravarana means invitation. What happens at the ceremony is everybody invites the rest of the sangha, and especially one virtuous member of the sangha, to please point out any remaining fault or offenses that I have. And so we invite that. So the Buddha said at that point there’s no need to ask people’s permission to point out the faults because the pravarana itself, each person is inviting them. So that’s tantamount to giving their permission.

We did that ceremony on Tuesday, and completed that, so that was the ceremony at the completion of the varsa. And nobody pointed out anybody else’s faults because we had all confessed our faults beforehand. So that was good. And then, because the sangha creates so much virtue by doing the retreat and by doing the invitation to conclude the retreat, then there’s kind of a celebration that comes about afterwards.

The history of that is that at the time of the Buddha it was very difficult for monastics to find cloth to make robes. I guess cloth wasn’t very prevalent at the Buddha’s time. So they would have to take scraps of cloth that they found by the roadside, or shrouds from dead bodies at the cemetery, or any little pieces that they found. Then they stitched it together in a pattern. That’s why our robes are made of different pieces. At the end of the varsa and the pravarana, a group of monks wanted to go see the Buddha and it was still raining at that time, so by the time they got to where the Buddha was, their robes were a mess. Plus, it was so difficult to get cloth, their robes weren’t great to start with. And then they were drenched and really in shambles by the time they reached the Buddha.

And so the Buddha, as a way of kind of celebrating the fact that the monastics had done the varsa—the retreat and the invitation—then he said, during the next month—from the end of the varsa for one more month—you can hold a kathina ceremony.

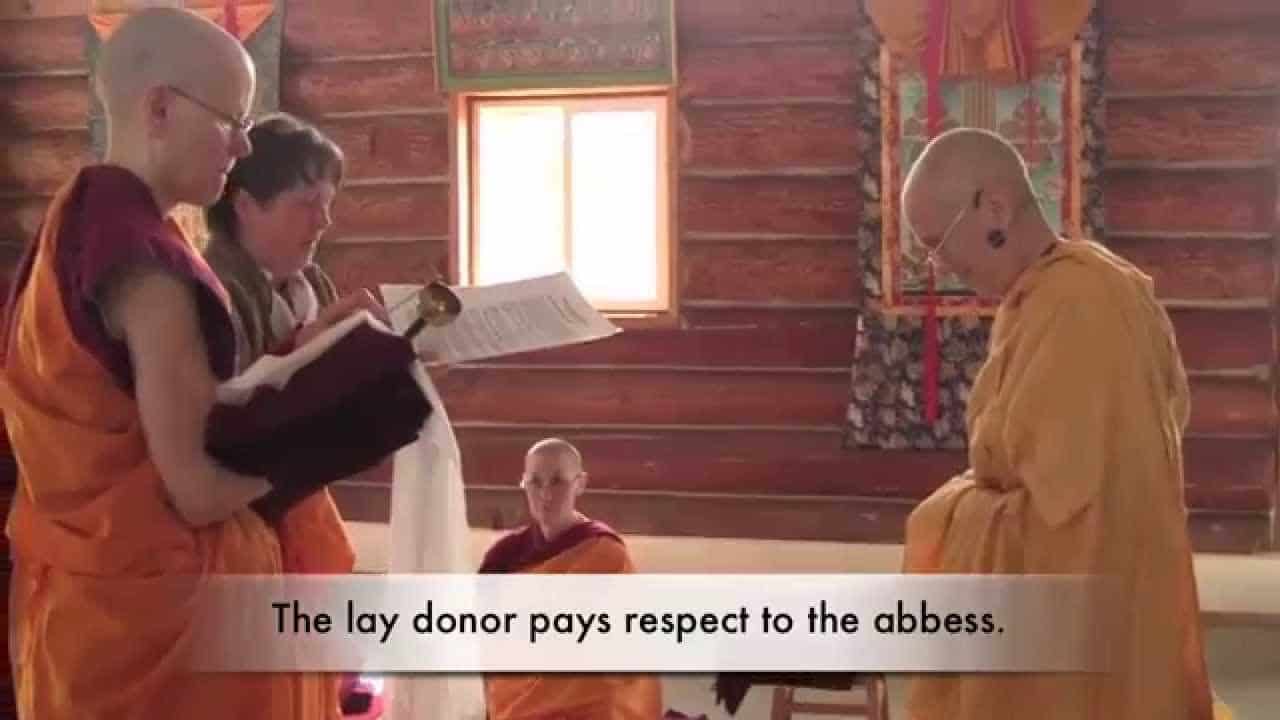

So, a kathina is a frame that they used to use for stretching material or cutting material when they were making robes, but the name kathina came to mean not only the day, and what we’re celebrating, but also the robe or the cloth that was being offered to the sangha. And also the privileges that the sangha receives after that, because as a way of celebrating their virtue then they receive five privileges for the next four months. So that’s what today is all about. It’s the offering of a robe. It’s called the “robe of merit” because it’s offered to the sangha, which is filled with merit after doing the retreat and the invitation. Offerings that are made on the kathina day are especially potent and especially really wonderful, you know, because the sangha has really been working on their minds, so the object that you’re offering to is kind of on the path, going towards awakening. It creates incredible amount of virtue at that time. One of the main things that the people bring is cloth to make robes, or they make a robe beforehand and then offer the robe of merit to one of the sangha members who has the most worn-out robes or to one of the seniors. So most everybody (at the Abbey), except one person, their robes are pretty okay because they haven’t been ordained for decades and decades. So the sangha selects somebody to be the robe recipient on behalf of the sangha. And then for the next four months the certain privileges start.

So today we asked Tracy to be the representative of all the laity because there are many people far and wide who live close by, who live internationally or nationally, who can’t be here today for whatever reason. And so she’s acting as the representative of all the supporters in offering the robe of merit to the sangha.

And Tracy, we asked you to do it because from the very beginning of the Abbey you were here. When the one nun and two cats arrived, moving in, then you were here and the kitchen was full. And you had a pledge never to let the sangha starve and as a result we are all very well nourished. Of course there are many people who support you and help you in doing it. You are acting as a representative of all of those people.

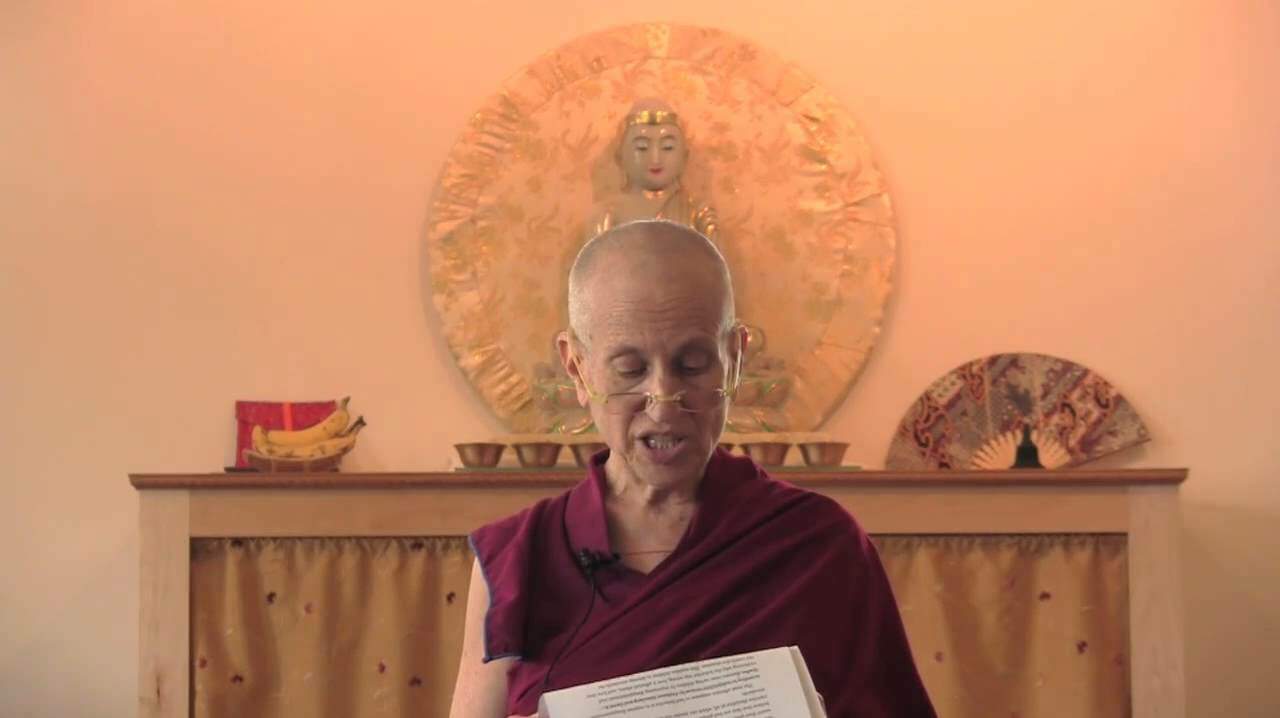

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.