Christ the divine physician sadhana

Medicine Buddha Sadhana

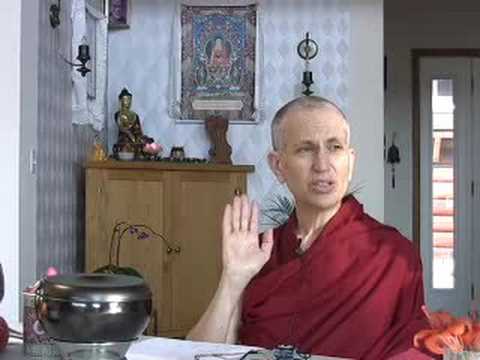

Venerable Thubten Chodron, foundress of the Tibetan community of Sravasti Abbey, invited me to make a 30-day retreat with her Buddhist community. I am a Carmelite hermit living in a laura community with another Carmelite hermit in the wilderness of eastern Washington about fifteen miles from Sravasti Abbey. We have 80 acres and six hermitages and offer solitude retreats to our Carmelite nuns from all over the United States. To learn about prayer from another great prayer tradition—Buddhism’s—was a unique and privileged invitation and opportunity.

Sister Leslie (right) considered her 30-day Buddhist retreat one of the great graces of her life.

Before the retreat I was given a copy of the prayers for the Medicine Buddha Sadhana (practice) and told that I could substitute words as needed in order to make it my own Christian practice. And it is true that as a Carmelite nun I could not relate to Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, so I substituted Christ, Gospel and Church/saints. Also, the Buddhist mandala didn’t hold a meaning for me, and so I substituted the circle of the host of the Blessed Sacrament for my mandala. Further, as a musician the chanted Tibetan mantras sounded beautiful to me, but didn’t hold a meaning content that I spiritually related to, so I chose instead the great koan of Jesus: “This is my Body.” I expanded on this mystery, adding to my chant, the words: “This is your body. This is our body.” I used the basic melody line of the Tibetan chant for this three-part koan chant, even though it doesn’t have the pleasing rhythm and flow of the Tibetan language. Not knowing the meaning of the symbols of the visualizations of the Medicine Buddha Sadhana, I chose two Christian icons to use for my meditation and visualizations—an icon of the Trinity and an icon of Christ under the aspect of mercy. Other icons of Christ could certainly be used. I had my own hermitage for the retreat and the Blessed Sacrament in my prayer spaces. Because the koan “This is my Body; this is your body; this is our body,” represents the mystery of the Blessed Sacrament it would be ideal to pray the Christ the Divine Physician prayer in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament.

On our retreat we had five meditation periods a day—ranging in length from 1 hr. 45 minutes to 1 hr. 15 minutes. The Sravasti community was instructed to do the Medicine Buddha Sadhana at all five sessions. I told my Buddhist friends that I would do my Christ the Divine Physician prayer at two of my sessions, but that at the other three I would pray in my usual more Carmelite way—in recollection in a more wordless manner—through the humanity of Christ.

After about a week of praying with the community, I discovered that for Tibetan Buddhists meditation doesn’t just mean sitting in mindfulness of the breath. Tibetan prayer includes a lot of visualizations as present in the Medicine Buddha Sadhana, as well as in the many analytical meditations based on the Lam Rim. We Christians would refer to these as discursive meditations. The Lam Rim includes meditations on such things as the disadvantages of attachment, anger, jealousy, pride, as well as their antidotes, and meditations on death, impermanence, dependent arising, Karma, emptiness, and re¬birth.

Though some of these meditations were helpful to me as a Christian for insights into motivations or aids for building on virtue and compassion, other meditations could only apply to the Buddhist metaphysics and views of ultimate reality. Saint Teresa of Avila wrote that she couldn’t do discursive meditation herself and found it tiring. For myself, I did find some of the meditations helpful, but others tiring, distracting or inapplicable to my spirituality as a Christian. Also, various members of the Buddhist community led the meditations with varying degrees of comfort or inspiration in doing so.

I was surprised that Tibetan Buddhist meditation left much less room for silence than Carmelite prayer. I realized that I didn’t know that there were so many varieties of Buddhism, and that what I had in my imagination about Buddhist prayer was Zen, vipassana and what I had read from Thomas Merton and William Johnston, S.J. Tibetan Buddhism is more opulent (like Catholicism) in the accoutrements of the meditation hall and in its many rituals. With all the ritualistic bowing, chanting, and guided meditations there really wasn’t that much time for silence for the Buddhists.

After about a week of praying my first version of the Christ the Divine Physician prayer, where I had substituted Christian words for Buddhist words, I realized the prayer still wasn’t right and didn’t reflect my Christian Carmelite sensibilities. All those nuances of sensibility would take too long to enumerate, but I will just briefly speak about one of those sensibilities, which is a core theological sensibility. There is a lot about getting rid of suffering and obtaining happiness for all sentient beings in the Medicine Buddha Sadhana. That is not really the main aim for Carmelites, though we certainly want the alleviation of suffering and the fullness of joy for others whenever possible. In the Carmelite tradition, St. John of the Cross teaches us that “the purest suffering produces the purest understanding”. In The Sayings of Light and Love, #54 John writes: “It is not the will of God that a soul be disturbed by anything or suffer trials, for if one suffers trials in the adversities of the world it is because of a weakness in virtue. The perfect soul rejoices in what afflicts the imperfect one.” And in his drawing of the Ascent of Mt. Carmel John states that neither his personal suffering nor glory matters to him. Carmelites are taught to be detached from everything—inc1uding happiness and suffering—detached from everything except the honor and glory of God. So in this mind set the four noble truths of Buddha would not be the most compelling aspect of reality.

After some realizations flowing from hearing the Buddhist’s prayer and mine, and realizing that Christians don’t have enlightenment as their highest aim, but rather the love relationship with the Lover, God through Christ in the Holy Spirit, I had to change the Christ the Divine Physician prayer more substantially. Striving for enlightenment, to me, still seemed to be of the ego self even though it does benefit the true self and others. So I realized that I had to change the focus of the Christ the Divine Physician prayer from desired states of being, or desired dimensions, to the desired love relationship with the Divine Persons of the Trinity. Further, I had to change the agency of the prayer. Buddhism’s focus is more on the human agency for ending suffering and bringing happiness and saving sentient beings. Christian sensibilities see these matters as the saving work of Christ to which we contribute our efforts in and through Him.

These are only a few theological realizations of what could be drawn out of the content of these particular prayers—either the Medicine Buddha Sadhana or the Christ the Divine Physician Prayer. Prayer reflects a view of reality itself–of self, the Divine, the world.

I’m not sure how the Christ the Divine Physician prayer could generally be used. Beyond being a substitute for any Christian who might be making a Medicine Buddha Retreat it could possibly be used in other more likely situations. It could be used as a special group prayer for a healing service in a parish or by anyone who is praying for healing for any injuries resulting from the Church as institution. It could be prayed for the healing of a family member or friend who is stricken with a serious illness. It takes in the whole world of suffering and could well be prayed weekly or monthly by anyone seeking to change the suffering of the world at large.

I consider my 30-day retreat with the Buddhists one of the great graces of my life. It deepened my understanding of Buddhism and my own beliefs, and I discovered what we have in common. I came away utterly impressed with their dedication to compassion, growth in virtue and working positively with the mind. I treasure my friendship with them and continue to discover ways that what I learned from them has helped me in my life choices and prayer since the retreat.