Western monastic life

Western monastic life

Report on the 12th annual gathering of Western Buddhist monastics, held at Bhavana Society in High View, West Virginia, June 26-30, 2006.

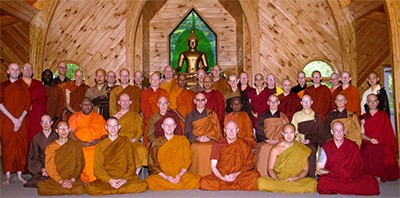

Our twelfth annual Buddhist Monastic Conference was held at Bhavana Society, in the lush hills of West Virginia. This was the first time the gathering was held at a Theravada monastery, and Bhante Gunaratana, the abbot, welcomed us warmly in the tranquil meditation hall. About 45 monastics were present, most of us Westerners, many who have been ordained more than 20 years. Many of us knew each other from previous conferences; newcomers were welcomed, and we checked in about the goings-on with other monastics who were unable to attend this year.

We meditated together and also listened to presentations from speakers of the various traditions. These talks sparked the discussions that followed, some of which were in small groups and some with the entire large group. Our discussions flowed over into the break times—our interest in learning from each other and the ensuing friendships that developed were strong.

In traditional Theravada fashion, we ate from large alms bowls. But with a new twist, we received the kindly offered food by order of seniority regardless of gender, not in the usual manner with the monks first followed by the nuns. One morning we went on alms round, with some monastics going into the nearby town where supporters offered food. Others of us walked to the homes of Bhavana’s neighbors who invited us. I was in the group led by Bhante Gunaratana, who at nearly 80 years of age had us younger ones panting behind him as we walked the three miles to a neighbor’s home. We were greeted with waves from people in passing cars and waved to them in turn.

The first presentation was given by Rev. Daishan, a Zen monk from the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives who lives at Shasta Abbey. He spoke about celibacy being the core of monastic life, a commitment that is ongoing and that an individual monastic makes on a daily basis in his or her practice. We discussed the entry procedures for many of the monasteries represented at the gathering. Prospective candidates are screened carefully to ensure they have suitable external and internal conditions to train in monastic life. Open, yet discreet, communication in communities is important to help people when challenges arise.

Bhikshuni Heng Liang, a nun from the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association who had trained at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, gave the next presentation and spoke about the development of Dharma Realm Buddhist Association and the changes that had occurred after its founder, Master Hua, passed away ten years ago. The passing on of a founder and strong leader was of concern to all of us. For some organizations in the West, this has occurred already; in others it will happen due to the nature of impermanence.

We talked about different ways monastic communities are formed. In some cases, one or more lay patrons establish a place and invite the sangha there. In other cases, a teacher decides to establish a monastery and seeks lay support to do so. In both cases, the relationship with the laity is important. The Buddha set up this relationship in a particular way involving mutual generosity: the monastics shared the Dharma and the laity shared the four requisites (food, clothing, shelter, and medicine). While monastics are training in letting go of worldly desires and concerns, the Middle Way isn’t to cut off all contact with the world. We are a part of society and as such we serve others by teaching the path to enlightenment, counseling people, and doing other works that benefit them.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, an American monk who has translated most of the Pali Canon into English, gave a stunning talk in which he explored: Does the way mindfulness is popularly taught in Western Dharma centers correspond with the way it is traditionally explained in monasteries? The Buddha taught mindfulness in the context of the four noble truths, which is rooted in the belief in rebirth in which we ordinary beings revolve in cyclic existence under the control of ignorance and craving. The Buddha’s principal reason for teaching the Buddhadharma was to lead us on the path to liberation from cyclic existence, and in the context of the Four Noble Truths, mindfulness is an essential factor in the path to liberation. It seems that many lay teachers extract mindfulness from that context and teach it as a technique to heighten direct experience and remedy the alienation and existential suffering people today suffer from. While beneficial in alleviating current ills, this use of mindfulness does not lead to liberation from cyclic existence.

This led us into a fascinating and heartfelt discussion in which we expressed our concerns about the fragility of the existence of the Buddha’s teachings in the West, the importance of the monastic sangha being firmly rooted in Western countries, and the beauty of the monastic life. The next day, Bhikkhu Bodhi challenged us with the question: As monastics, do we talk about the benefits of “going forth”—as the Buddha called becoming a monastic—to our students? Do we encourage people who are interested to live a life of simplicity and ethical conduct or do we, too, downplay the value of monastic life in accordance with the West’s faith in consumerism, materialism, and sexual pleasure as the path to happiness?

Khenmo Nyima Drolma, a student of Chetsang Rinpoche and the abbess of Vajradakini Nunnery, spoke of four criteria she uses in establishing a monastery in the U.S.:

- What advice do respected teachers give?

- What do texts say?

- What changes were made when monasticism and Buddhism went to Tibet?

- What do Western students need to facilitate their understanding and practice due to their culture?

I was asked to speak on recent developments in the Tibetan tradition regarding the possibility of introducing the bhikshuni ordination, the full ordination for women. In the ensuing discussion, Bhante Gunaratana and Bhikkhu Bodhi both expressed their support for having fully ordained women in the Theravada tradition.

Our monastic conferences always bring home to me the unity of the various Buddhist traditions. On a personal level, being with other monastics—people who understand how I’ve chosen to live my life—is edifying. But most importantly, I feel honored to be with people who are training in ethical conduct, and whose goals are liberation and service to living beings.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.