Precious human rebirth

Verse 4 (continued): Eight freedoms and ten fortunes

Part of a series of talks on Lama Tsongkhapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path given in various locations around the United States from 2002-2007. This talk was given in Missouri.

- Differentiating Dharma practice from worldly practice

- Recognizing the eight freedoms and the ten fortunes

- Analytic meditation on the precious human life

Three Principal Aspects 05a: Verse 4: Precious human life, freedoms and fortunes (download)

Understanding the difference between what’s a worldly motivation and what’s a Dharma motivation is crucially important. How are we going to practice the Dharma if we can’t differentiate what’s Dharma practice and what’s worldly practice? Remember that story I told last time about the guy circumambulating and then doing prostrations and then reciting the text? He thought the whole time he had a Dharma motivation because his actions looked like Dharma practice. But he didn’t have a Dharma motivation because he was doing them with a worldly mind—a mind seeking reputation, or a mind seeking praise, or a mind seeking some kind of special power, or a blessing for this life only. Even though that person’s action looked like the Dharma it wasn’t the Dharma because the mind wasn’t the Dharma.

We should constantly check our motivation to see if we have a pure one or not.

In our own lives, if we say we’re Dharma practitioners, we have to check how often we actually have Dharma motivations in our mind. If we don’t really check our motivation, we can go through our whole life saying, “I’m practicing the Dharma.” But we never really practice it because our mind is continually seeking the eight worldly concerns. We haven’t given up attachment for the happiness of this life.

We really need to know what this demarcation line is between Dharma and worldly activities, and then look at our own mind and see. Is our mind actually pursuing Dharma, seeking an upper- rebirth, or liberation, or enlightenment? Does our mind have a Dharma motivation in which we’ve given up attachment to the eight worldly concerns seeking the happiness of this life? Do we have that motivation at that moment? Or instead, is our motivation really involved with the eight worldly concerns but on the outside we’re making it look like Dharma practice—in which case actually we’re wasting a lot of time.

Very often our motivations can be mixed, there’s a little bit of eight worldly concerns and a little bit of Dharma motivation. In fact, I think a lot of times our motivations are like this. That’s better than having a motivation of the eight worldly concerns. But still, if we’re doing an action, since we’re doing it we might as well try and make our motivation as good as possible because the result of that action is going to depend on the motivation.

If we’re sitting down to meditate or to do some chanting or reading some text, then whether it becomes virtuous and the cause for enlightenment, or whether it becomes neutral karma, or even something non-virtuous depends so much on the state of our mind. If I’m sitting here thinking, “Okay, I’m going to read this Dharma text and I’ll gain some knowledge. And then I’ll go teach people and then people will think I’m a great practitioner and I’m a great teacher. I’ll have a very good reputation. People will make offerings to me.” You can become a great teacher that way and be very famous and get a lot of offerings, but are you practicing the Dharma? No, there’s no Dharma practice because the motivation is totally eight worldly concerns. The person who’s done that has basically just wasted so much time and energy; not really getting the benefit from what they’re doing because their motivation was polluted.

It’s the same thing with us—constantly checking our motivation to see if we have a pure one or not. It’s very difficult to have a pure motivation. That’s why I said those of us who are trying a little bit very often have mixed motivations, a little bit of Dharma and a little bit of worldly. It’s better than nothing but it’s still not the best we can do. We should try to be aware and mindful and purify our motivation as much as possible. That’s why I really emphasize this point—we have to know what is the demarcation line between Dharma activity and worldly activity. If we don’t know that, how are we going to check if our mind is a Dharma mind or not?

The more you stay in Dharma circles, the more you can see how this happens. People do a lot of things that look like Dharma but it’s not really Dharma. We can even start observing our own mind. See how our own ego cheats us by putting a very base motivation in an activity that could potentially be pure, but isn’t, because that sneaky motivation has come in there. It’s very sneaky. Very sneaky. It comes up all the time. We come to Dharma classes, “I want to look like a very good practitioner. I want to sit up straight, have very good meditation position because then all the new people, they’ll think that I’m really a good practitioner. Look at how well I sit in meditation, how well I listen to teachings. They’re going to think that I’m an old student and that I really know a lot.” That kind of stuff very easily goes on in our minds when we listen to teachings, very easily. Just watch. Check. Or maybe it’s only me that has that problem!

We also talked about The Ten Innermost Jewels of the Kadampa and how practicing those help us give up the eight worldly concerns. Go back over and review that and then I’ll ask you questions about that before next session. Right now I want to continue with going into the teaching here.

In the outline of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path the first one was renunciation or the determination to be free. That had three outlines: the reason why we should develop it, how to develop it and the point at which we have succeeded in developing renunciation. We were on the second outline: how to develop it. That one has two parts: how to stop the desire, the attachment for this life, and how to stop the attachment for future lives. Of those two we were still at the first one: how to stop the attachment for this life. We talked about the eight worldly concerns because they’re the embodiment of attachment to the happiness of this life. Then we talked about The Ten Innermost Kadampa Jewels because those are that things that, when we sink our mind into them and try to cultivate them, they oppose the eight worldly concerns.

Stopping attachment to this life

Let’s go back over that one sentence that was about how to stop desire for the present life. It says

By contemplating the leisure and endowments so difficult to find and the fleeting nature of your life, reverse the clinging to this life.

If somebody says, “How do you stop the attachment to this life? How do you stop it?” This sentence tells us how. First we contemplate the leisure and endowments, or sometimes I like to translate it the freedoms and the fortunes, of a precious human life. That’s one way to stop the clinging to this life. A second way is by contemplating the fleeting nature of our life, in other words, meditating on impermanence and death. If you look at the lamrim these two meditations on (1) precious human life, and (2) impermanence and death come right at the beginning of the lamrim. This is because they are what help us give up the attachment to this life.

Let’s talk a little bit about these two meditations. You see, just in one short sentence there, there’s a whole lot of meaning, there’s a lot of teachings. We’re probably going to spend at least four days on just that one sentence. Let’s talk about the leisure and endowments. Let’s talk about the precious human life.

In the lamrim when we talk about the precious human life, there are three basic outlines to it. One is recognizing the eight freedoms and the ten fortunes, what is called here the leisure and endowments. The second is considering the importance of our precious human life. And the third is the rarity and difficulty of attaining a precious human life. So those are the three major outlines under the topic of a precious human life: recognizing the freedoms and fortunes, considering the importance of a precious human life, and the rarity and difficulty of attaining one.

Let’s look at the freedoms and fortunes. These come from the scriptures. I believe they’re also in the Pali scriptures as well. In some reading that I’ve done I’ve seen these. The eight worldly concerns are talked about in the Pali scriptures also.

Eight freedoms of a precious human life

Let’s look at the eight freedoms. These are eight states that we are free from being born into. If we were born into any of these eight, it would be very difficult to practice the Dharma in this particular life. The whole purpose of contemplating this is so that we really feel how precious our life is and make good use of it.

First, we can rejoice that we’re not reborn in the hells this life; second, that we’re not reborn in the hungry ghost realm; third, that we’re not reborn as an animal; and fourth, that we’re not reborn as a god. These four lives, those four, make it very difficult to practice the Dharma. If you’re born in the hell realms you’re experiencing so much pain that it’s impossible to turn your mind to the Dharma. If you have any doubt about it, just think of how your own mind gets when you get sick. When we get sick, when we’re suffering, it’s very hard to practice. So if we’re born in the hell realm, difficult to practice; same with the hungry ghost realm. Here again we can look at our own life. The characteristics of hungry ghosts are running around with so much clinging and dissatisfaction. Well, when our mind is in that state it’s difficult to practice. It’s the same if you’re born in that realm.

If you have doubt about if animals can practice the Dharma, well, the main characteristic of an animal is somebody who’s dumb. When our mind gets foggy it’s difficult to practice. I mean, look at the cats. Our cats and our dogs have the fortune to be born in a monastery, to live in a monastery. Imagine that. But are they practicing the Dharma? You try to teach the cats not to chase mice and not to kill mice. I always tell Achala and Manjushri, “The mice want to live just as much as you do,” but they don’t get it—impossible to practice. And if you try to teach Naga to do some Dharma practice, he’ll just wag his tail and wait for you to throw the stick. So if we’re born in that kind of realm it’s very difficult to practice.

Now thinking about this requires some belief in rebirth and some feeling that we’re not always who we are right now in this particular life. That might take us a while to feel comfortable with. I know I certainly didn’t believe in rebirth the first time I attended a Buddhist teaching. I wasn’t brought up with that concept as most people in Asia are. When I look at my mind I can certainly see characteristics of the other realms right in my mind now. If I take a certain mental state and just exaggerate it? Yes, you could have a body of a being in that realm. Why not?

Animals. We know the animal realm exists. We see them. Now I could think, “Well, I’ll never be born as an animal.” Well, why not? Do I think I’m always going to be me? If I think I’m always going to be me then I don’t have a clue about selflessness, do I? If I always think that who I am is affiliated with this body, then I haven’t thought about impermanence and the fact that I’m going to leave this body sometime. Sometimes if we do just a little bit of reflection about selflessness or impermanence it helps us to understand the idea of rebirth better. It loosens the grasping at the idea that I am just who I am right now in this particular body. We can rejoice that we aren’t born in those four realms.

If you want to meditate on this, it’s really rather interesting to think, “Well, what would it be like if I were born in those realms?” Then if we believe in rebirth to think, “Well, in beginningless previous lives I have been born in those realms. And could I practice then?” If I was born as naga could I practice the Dharma? Difficult, yes? How about if I were born as one of the termites? When all the termites were coming out I looked at them, I mean they’re sentient beings, aren’t they? They have consciousness. They want to be happy and free of suffering. Yet their minds are totally obscured. I thought, “What kind of karma to be reborn as a termite, in a monastery yet.” They’re so close to the Dharma. They’re even eating the monastery. They’re very close to the monastery but have no opportunity to practice because the mind is just totally obscured because of the type of body that being has been born into.

There are four kinds of human lives that we haven’t been born into this life. We can rejoice that we haven’t been. One is to be reborn as it says, “as a barbarian among uncivilized savages.” What it means is in a country where there’s no Dharma. For example, being reborn in a country under Communist control where Dharma is severely repressed—like being born in the Soviet Union under the Communist regime. Very difficult even you have spiritual aspiration for where are you going to go for Dharma teachings?

The second is being born in a place or at a time when the Buddha’s teachings are unavailable—where a buddha hasn’t appeared and taught. Let’s say we were born 3000 years ago before Shakyamuni appeared. Then there was no chance to learn the Dharma at least in this world system.

Third is being born with impaired senses. It doesn’t mean that those people can’t practice the Dharma but there’s a lot of impediment. Nowadays it’s better actually. In ancient times if you had a sight impairment you couldn’t read the scriptures. Now they’ll have Buddhist books read on audio tapes and maybe something in braille, so it’s easier. Same with having an auditory impairment in ancient times: very difficult to listen to teachings. Now I’ve taught at times where somebody signed the teachings so that people can hear them. Still it makes it harder, so we can rejoice that we don’t have that impediment right now.

Lastly, is being born as somebody who has wrong views. For example, being born the child of a Taliban officer in Afghanistan and being raised with the Taliban view of life. You’ve grown up with incredible wrong views and it’s going to be very difficult to practice.

It can be very helpful for us to appreciate our lives, to really think, “Well, what would it be like if I had been born in some other place or time than where I am born now?” Did you ever think about that when you were a kid? Did you ever wonder why you were born you? I used to wonder, “Why am I born me? Why wasn’t I born someone else?” Then you think how easily we could have been born somewhere else. It makes it so difficult to practice.

Ten fortunes of a precious human life

Then the ten richnesses, the ten good qualities we have.

- First is that we’re born human. With a human body then we have human intelligence. This is really something to rejoice at.

- Second is living in a central Buddhist region. This is a place where you can receive the teachings and where you can receive ordination. Actually, when I first started practicing the Dharma I don’t know if I lived in a central Buddhist region or not. I don’t know even if they were giving ordination in this country at that time.

- The third is having complete and healthy sense faculties: so being able to see, being able to hear, having our mind be sharp.

- The fourth is not having created any of the five heinous crimes. These five heinous actions are ones that if you commit them, then in your next life you instantly get reborn in a hell realm because of the severity of these actions. They include killing our father, killing our mother, killing an arhat, causing schism in the Sangha, and causing blood to be drawn from a buddha. We haven’t committed any of those.

- The fifth is we have an instinctive belief in things that are worthy of respect. We have in our hearts an instinctive interest in the Dharma, an instinctive curiosity about spiritual practice. This is something quite precious in us: that curiosity, that inspiration and aspiration for the Dharma. We should respect that part of ourselves and cherish it. You look all around and there are so many people, I mean, look in the town of Augusta. How many people have interest in the Dharma and aspiration to practice it? Not so many. Just having a human life doesn’t mean we have a precious human life. A precious human life means that we have all the conditions for Dharma practice.

- The sixth of the ten fortunes are that we live where and when a Buddha has appeared. In our case Shakyamuni Buddha has appeared and manifest and taught the Dharma.

- The seventh is where and when a Buddha has not only appeared but taught. So the sixth is a Buddha has appeared, the seventh is that he has taught.

- The eighth fortune is that the Dharma still exists. We’ve been born at a time when the lineages of the Dharma that can be traced back to Shakyamuni Buddha—those lineages still exist. So we can receive the teachings.

- The ninth is we live when and where there’s a Sangha community following the Buddha’s teachings. Having a monastic community in the place we live is very important because the monastics uphold the precepts given by the Buddha. They have the time to really study and practice and teach the Dharma. Having that kind of time is difficult as a lay person. It’s nice to have that example of other Sangha members for us to follow; and to be able to go to them for questions and support in our practice.

- The tenth is that we live when and where there are others with loving concern. Loving concern refers to benefactors—the people who offer us food, clothing, medicine, and shelter (the four requisites) so that we can practice. Loving concern also refers to the people who are our Dharma teachers. They teach us with loving concern for our spiritual well-being. Having the support of others is very important for our practice.

Meditating on these eight freedoms and these ten fortunes can give us a very deep feeling of appreciation for our life. If we’re missing any one of them, we might have all the rest, but it becomes very difficult to practice the Dharma. For example, I remember my friend Alex telling me about a visit that he paid to some of the Eastern European countries before the fall of Communism there. He was telling me, I think it was in Czechoslovakia, when the people came for teachings they had to have the teachings in somebody’s house. There were no temples and you couldn’t rent a public place for the teachings because it was illegal. People had to come separately, at different times, to this person’s house because you weren’t allowed to gather in groups.

Then when everybody got there in the front room they would set up on the card tables and playing cards, like they were all playing games. They would leave that there with drinks and snacks and everything, but then they would go in the bedroom, in the back room, and he would teach them there. The reason they did that was in case the police came and knocked on the door: they could leave the bedroom, go sit around the table, and there they are playing cards. The police couldn’t catch them for having Dharma teachings.

Audience: [inaudible, something about making believe there’s a birthday party and not Dharma teachings going on.]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Right. So you think how lucky we are to be born in a place where we don’t have those kind of restrictions and that kind of fear. I mean, we just wake up in the morning and here we are. We can own Buddhist books. In Communist China in Tibet, there was a time where if you had Buddhist books you’d would get thrown in jail, quite literally. The books would be burned. You could be beaten and imprisoned. Even in Tibet at a certain time, if they caught you moving your lips chanting mantras or prayers, they would arrest you.

When I was in Beijing I met some people who were very devoted Buddhists. They were telling me about this offering ceremony that we do twice a month. When they did it they couldn’t do it even in their house. If the neighbors saw them chanting and doing a ceremony, the neighbors would report them to the police. What they had to do is turn out the lights, pretend like they had gone to bed, lie down and pull the blankets over their head. Lying down with the blankets over their head, take out a flashlight and whisper the chanting there to do their chanting ceremonies. When you hear stories like that…! And these people did that for years and years and years. They had such faith and devotion in the Dharma. I find that just totally admirable. Then we think, “Wow, I’m not born in that kind of environment. I have so much freedom. I can just go to my room anytime I want to sit and meditate.” How fortunate we are. We can walk around here chanting mantra out loud. We can have retreats and invite teachers and have Dharma classes and do all these things together. We’re just so incredibly fortunate.

It’s important to really think about this. Think about the positive attributes of our life and the good circumstances that we have so that we make sure that we make use of our life and don’t just fritter it away. When we take our good circumstances for granted, then we think, “Well, there’s really nothing so special about living here.” Then all we do is pick faults like, “Oh, it’s too cold. This morning was too cold. I can’t meditate. Now it’s too hot. I can’t meditate. This Missouri weather changes so much.” Or we complain, “Oh, I can’t meditate because the cats are meowing. I can’t sit and read a Dharma book because, blah, blah, blah.” And so we always complain, “Oh my stomach hurts, I can’t practice the Dharma. Oh, my middle toe hurts, I can’t practice the Dharma.”

In Seattle everybody had so many, not just in Seattle—everywhere—people have so many excuses why they can’t come to Dharma things, “Oh, it’s my daughter’s friend’s birthday, I can’t come to Dharma class.” Why not? I mean, some people find so many things that in their minds seem to be reasons why they can’t practice. Or people get depressed so easily. Even this country has so much wealth but people get so depressed and just concentrate on their problems: “Oh, my brother doesn’t like me.” “Oh, I didn’t get the promotion, somebody else got the promotion.” “Oh, this other person bosses me around.” “Oh, my neighbor plays their music so loud.” It’s, “Oh this, and oh that.”

I don’t know about you but I’m an expert at complaining. Just give me any chance and I can think of ten complaints right off the top of my head. That kind of mind that just complains all the time, or the type of mind that gets depressed thinking, “Oh, poor me. Everything about me is rotten and awful.” There’s also the mind that has so many reasons why we can’t practice because there are all these obstructions coming from ‘outside.’ All those kinds of minds create big obstacles to our practice. They all come because we don’t appreciate the good circumstances that we, in fact, live in. Instead we focus on one or two small things that aren’t going real well, and then just let our selves get distracted or despondent about those.

How to meditate on precious human life

If we really took time and meditated on precious human life; and really go through these eighteen. Think, “Well, what would happen if I wasn’t free like this and I had that obstacle.” Or, “What would happen if I didn’t have that one of the ten fortunes?” And imagine ourselves living like that. Then you go and meditate, and you pretend that you’re that kind of person who really has that obstacle and what it’s like. Then you come back and you’re yourself, and you go, “Wow, I don’t have that obstacle. Wow, I am so fortunate.”

When you’re meditating on precious human life, you’re doing what’s called checking or analytic meditation. Here we’re not meditating on the breath. Here we are thinking, like in this case, we think about each of these eighteen points. We go through them one by one. We think, “Well, what would it be like to be reborn in the hell realm? Could I practice there? Well, forget the hell realm, what would it be like if I were born in excruciating pain in this life? Could I even practice?” We go through each of the freedoms like that, “Now what would it be like if I were born the child of a Taliban officer?” Because there, but for a flick of karma, go I. Why weren’t we born the child of a Taliban officer or the child of a Nazi officer? Why weren’t we born as somebody in the Taliban, not even as a child of one, but somebody who was attracted to that view. Could we practice the Dharma?

Go through all these different kinds of situations. What would happen if I were born as somebody who deprecated the Dharma? Or who said Buddha just was a deadbeat dad who left his father and left his family. And what would we be like if we had a completely different attitude, a different birth? Then we see how incredibly fortunate we are.

Even among the people who are Buddhists, like all the people who were here yesterday, they’re all at work today. Yet we have all day to really work with our mind. We have work around here to do, but at least we have the leisure to generate a good motivation in the morning so that everything we do becomes the Dharma. We have some leisure time. We’re taking an hour out now to reflect on the Dharma, and talk about it, and think about it. We have morning and evening meditations when we can really practice. I mean, we’re so fortunate. Really thinking like this.

In this checking meditation we go through and we think about these things. Then from that we draw conclusions, like, “How fortunate I am!” They say that when you meditate on the precious human life like this you feel like a beggar who just found a jewel. Or if you want to put it in modern terms, you feel like you just found somebody else’s credit card and you know the pin. Not very nice, but in other words, in a worldly sense, how much joy you would have if you suddenly discovered that you were wealthy. Well, to really think about our lives and how wealthy we are in a Dharma sense. If we do that then our mind is continually happy. Then small things that happen in our life don’t become obstacles for us.

Considering the importance of a precious human life

The second outline under precious human life in the lamrim is considering the importance of a precious human life. Our precious human life is important and valuable for three reasons. First is that we can use it for temporal aims. In other words, we can employ this life to create positive karma so that we can have a good future rebirth. Second, and more important, is that this life is important and valuable because we can use it to create the cause for the ultimate aims, in other words, for liberation and enlightenment. When you think, “With this very life, in this very body, we can attain full enlightenment,” that’s so marvelous, so astounding to think!

Shakyamuni Buddha had a body and a life just like ours, and he did it! Many great sages in all of the Buddhist traditions attained enlightenment. They did so on the basis of a human life—a precious human life—just like we have. Look how valuable and important our life is, in other words, how meaningful our life is. I say this because so often, especially in the modern world, people have this existential angst feeling like, “My life is totally meaningless. My life, it doesn’t have a meaning. It doesn’t have a purpose.” Many people suffer from that. And so to really think, “Wow, my life has a very deep meaning and purpose. The purpose of my life isn’t just to make money.”

I used to think about this a lot. I don’t know if any of you have seen the movie The Graduate. You’re probably too young for that. It was a movie that was very popular when I was young. It was about a young man who just graduated from college and was wondering, “What’s the meaning of life?” That movie really spoke to me because as a teenager I looked and I said, “Well, what’s the meaning of life? Is it to just grow up and get married? And you have kids and you have a family. And you make money and you have a nice life. But then you die and it’s all over, and when you die none of this comes with you. So what’s the purpose of doing all this? At the end of the day, after you die, what good was your life? What use was it having lived?” Even as a teenager I was asking this question. This was one of the big questions that eventually propelled me many years later into the Dharma.

As a teenager I was thinking about this and I would ask the rabbis and the priests and the ministers and my teachers and everybody, “What’s the meaning of life?” Everybody just said, “Don’t think about that.” Or they said, “Be happy,” and the way to be happy is through the eight worldly concerns. Have those four things, that’s the way to happiness. That’s the purpose of life. But when you think about life from the perspective of death: the eight worldly concerns don’t bring any meaning and purpose to our life. They just leave it totally flat. So the fact of having a precious human life, which means we have the opportunity to practice the Dharma, gives us the potential to make our life really meaningful and purposeful.

The third way in which our life is important is moment by moment. In other words, each single moment we’re alive is potential Dharma practice. We do this through practicing the thought training.

This is the practice in the Chinese tradition of the gathas. You know how you have the gathas, the little verses or sayings for when you wash your hands; when you go to the toilet; offering our food; opening a door; going down stairs; going up stairs; handing a person something. In other words, all of our daily life activities—especially times when we’re cleaning. Cleaning is very easy to make a very valuable Dharma practice. Instead of just cleaning the dirt we think, “I’m cleaning the stains from the minds of sentient beings with the cloth of wisdom, with the soap and water of wisdom.” Or you go downstairs, and you think, “I’m willing to go to the lower realms to lead sentient beings to enlightenment.” When you go upstairs, “I am going upwards with sentient beings leading them to enlightenment.” Remember those Forty-one Aspirations of a Bodhisattva? They were all about common daily life activities that we can transform into Dharma activity by the way that we think.

There’s this one text that says when a bodhisattva does this, this is how they think. Or, “This is the prayer of a bodhisattva when they …” do a certain action. It listed a bunch of them. Then I had the people at DFF [Dharma Friendship Foundation] write their own. It was very cute. People came up with all sorts of good things—because the text we were going through was written many centuries ago. So they came up with, “When I turn on the computer, I’m turning all sentient beings on to the Dharma.” “When I turn off the computer, I am closing the door to lower rebirth for all sentient beings.” It was quite nice—so that every single moment became Dharma practice. So that’s another way in which our life is very important and valuable.

We’ve covered two of the three outlines for precious human life. The first one was recognizing the freedoms and the fortunes. We talked about the eight freedoms and the ten fortunes. These are translated leisure and endowments in the text here. We also talked about the second point, the importance, or the value, the meaning, the purpose of a precious human life. These are things for us to reflect on in our meditation. In other words, they’re not just things that we listen to right now or write down in our notebook and then tell other people. They’re things that we actually sit and contemplate ourselves—we think about and apply to our own life. If we do this it definitely produces a change in attitude and a shift in our consciousness.

Okay, questions, comments?

Audience: You said in the second outline of a precious human life, the first one is you can use it for temporal …

VTC: The second outline was the importance of a precious human life. And under that there are three points. One is the temporal purposes, so gaining a good rebirth. Second is the ultimate purpose, we can use this very lifetime to attain liberation and enlightenment. And third was we can make our life meaningful moment by moment by employing all these thought training practices.

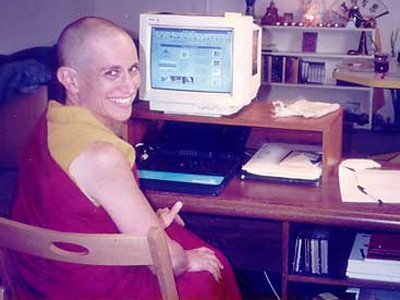

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.