Foreword

Foreword

From Blossoms of the Dharma: Living as a Buddhist Nun, published in 1999. This book, no longer in print, gathered together some of the presentations given at the 1996 Life as a Buddhist Nun conference in Bodhgaya, India.

I met Venerable Thubten Chodron when we were suite-mates at a large hotel, some years ago, along with three other women presenters at a week-long Buddhist conference. I was touched that her being a nun did not create a sense of separation from the rest of us—we were all women devoted to practicing and teaching the Dharma, and all of us enjoyed an easy delight in meeting and being with each other. I was inspired to realize that, notwithstanding the intensity of the conference all day and our hours of conversation at night, Chodron was up long before anyone else doing her morning prayer practice. She clearly loved the life she had chosen and could gracefully interpolate it into the life she shared with all of us.

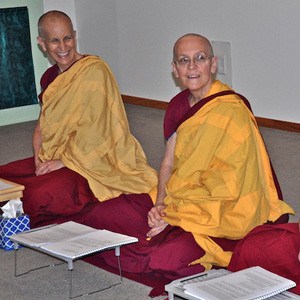

Monks and nuns are symbolic of the path to which all Dharma students are committed. (Photo by Sravasti Abbey)

Monks and nuns, people who dedicate their entire lives to practicing and teaching the Dharma and to living the renunciant lifestyle, are symbolic of the path to which all Dharma students are committed. The Buddha taught the method for transforming the heart through this special structure for training the mind and serving others. We lay people assume that special structure and discipline during meditation retreats. It is important to have people in our community who take it on for a lifetime. We need monastics at our core.

The teachers at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Marin County, California are lay teachers, and our students are men and women of all ages, from many social and cultural communities, including people with enduring connections with other faith traditions. In July of 1998, at Spirit Rock’s opening day ceremony, Ajahn Amaro, a Theravadin monk and our friend and neighbor, lead the procession of teachers into the meditation hall as we all chanted homage to the Buddha. His doing this was important to our teaching faculty and meaningful to everyone.

The potential influence of Buddhist nuns and monks is much wider than just our own community. Recently I noticed the cover story of a well-known business weekly magazine was “Is Greed Good for You?” I was sure the title was a joke and the story would be a values reminder, so I read the article and was dismayed to find that it was serious. Thinking of this book of nun’s stories, I know that in a culture believing consumerism and materialism to be the source of happiness, the visible presence of renunciants in the society is an important reminder. It is a teaching in itself. Ancient texts tell us of King Asoka who had led his people in a terrible battle in which many were slain. The following morning, as he surveyed the scene of the conflict, King Asoka also noticed the serene, peaceful presence of a Buddhist monk. Seeing him, Asoka regretted the violence and was moved to become a student of Buddhism. In so doing, he converted his entire kingdom and instructed them in wise conduct. My hope is that just as King Asoka’s vision converted him to non-hatred, the presence of monastics in our society will serve to convert our culture to non-greed.

Whenever I read historical accounts of Buddhist nuns, I admire their valor. Cultures have not supported women in choosing the renunciant life, and in the Buddhist world, too, their position has generally been secondary to men. It is important for us as modern Buddhists to read these accounts of contemporary women with their goals, hopes, difficulties, and triumphs. They are varied in background, come from all over the world, and span the spectrum of Buddhist lineages; but they all share the passion for a life dedicated to liberation, and their example can inspire all of us in our own practice.

Early in my own meditation practice, I dreamed that I became a nun. My dream was symbolic, representing my enthusiasm for practice and my hope for awakened understanding. For those women for whom the dream might become reality, we need communities of nuns who study, practice, and teach, and we need the stories of the women in this book to make this choice widely known and available.

Sylvia Boorstein

Sylvia Boorstein grew up in Brooklyn, New York. All four of her grandparents arrived in America, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, between 1900 and 1920. Sylvia went to Barnard College and majored in Chemistry and Mathematics. She earned a Master's Degree in Social Work from the UC Berkeley in 1967 and began working as a psychotherapist. At the College of Marin in Kentfield, California from 1970 until 1984, she taught psychology, Hatha Yoga, and introduced and taught the first Women's Studies course. In 1974, she was awarded a Ph.D. in Psychology from Saybrook University. She was a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and the Marin Women for Peace. She marched, accompanied by her four young children, two sons and two daughters, in rallies protesting the Vietnam War. A few years ago, she was part of a clergy peace rally, and agreed to be arrested, along with friends and colleagues, as a protest to the invasion of Afghanistan. Her first Mindfulness mediation experience was a weekend retreat in 1977 in a private home in San Jose, CA. Her main teachers since that time have been Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberz, and Joseph Goldstein. She began teaching meditation in 1985 and has taught a weekly meditation class at Spirit Rock for fifteen years. (Photo and bio courtesy of SylviaBoorstein.com.)