Living the Dharma

Living the Dharma

From Blossoms of the Dharma: Living as a Buddhist Nun, published in 1999. This book, no longer in print, gathered together some of the presentations given at the 1996 Life as a Buddhist Nun conference in Bodhgaya, India.

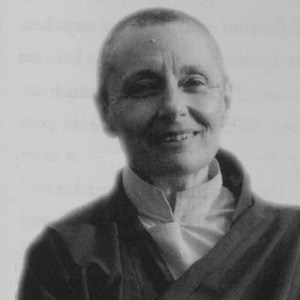

Khandro Rinpoche

We all are aware of the problems we face today, and we are also aware of the potentials and the qualities present in the female sangha. When there is a talk about women and Buddhism, I have noticed that people often regard the topic as something new and different. They believe that women in Buddhism has become an important topic because we live in modern times and so many women are practicing the Dharma now. However, this is not the case. The female sangha has been here for centuries. We are not bringing something new into a twenty-five hundred-year-old tradition. The roots are there, and we are simply re-energizing them.

When women join the sangha, sometimes one part of their minds thinks, “Maybe I won’t be treated equally because I am a woman.” With that attitude, when we do a simple thing, such as enter a shrine room, we immediately look for either the front seat or the back seat. Those who are more proud think, “I’m a woman,” and rush for the front row. Those who are less self-confident immediately head for the last row. We need to examine this kind of thinking and behavior. The foundation and essence of the Dharma goes beyond this discrimination.

Sometimes you suffer from doubt and dissatisfied mind in your Dharma practice. When you do a retreat, you wonder if bodhicitta would grow more easily from actually working with people who are suffering. You think, “What is the benefit of selfishly sitting in this room, working toward my own enlightenment?” Meanwhile, when you do work to help people, you think, “I have no time to practice. Perhaps I should be in a retreat where I can realize the Dharma.” All of these doubts arise because of ego.

Dissatisfied mind arises toward the precepts as well. When you do not have precepts, you think, “The monastics have dedicated their lives to Dharma and have so much time to practice. I want to be a monastic too.” Then after you become a monastic, you are also busy and begin to think that being a monastic is not the real way to practice. You start to doubt, “Perhaps it would be more realistic to stay within the world. The monastic life may be too traditional and alien for me.” Such obstacles are simply manifestations of a dissatisfied mind.

Whether you are a monastic or a lay practitioner, rejoice in your practice. Do not be rigid or worry unnecessarily about doing things wrong. Whatever you do—talking, sleeping, practicing—allow spontaneity to arise. From spontaneity comes courage. This courage enables you to make an effort to learn each day, to remain within the arising moment, and then the confidence of being a practitioner will emerge within you. That brings more happiness, which will enable you to live according to your precepts. Do not think that precepts tie you down. Rather, they enable you to be more flexible, open up, and look beyond yourself. They give you the space to practice the path of renunciation and bodhicitta. It must be understood that by taking the precepts we are able to loosen our rigid individualism in many ways and thus be more available to others.

Previously, many women lacked the confidence that they could achieve enlightenment, but I think that is not much of a problem now. Many women practitioners, lay women as well as nuns, have done incredible work. Different projects are underway and our external circumstances are improving. Nevertheless, some people ask, “How can we practice with the shortage of female role models to teach us?” I wonder: Does the teacher you dream of have to be a woman? If so, will you want to spend as much time as possible with her? Our wants and wishes never end.

I agree there is a great need for women teachers, and many young nuns are exceptional in their education today. We should definitely request them to teach. Many nuns simply need the confidence to teach and thus to help one another. To learn, you do not necessarily need a teacher who has studied thousands of texts. Someone who knows just one text well can share it. We need people who will pass onto others what they know now.

But our ego blocks us from learning and benefiting from each other. Those who could teach often doubt themselves thinking, “Who is going to listen?” And those who need to learn often look for the “highest” teacher, not the teacher with knowledge. Looking for the “perfect” teacher is sometimes a hindrance. You think, “Why should I listen to this person? I have been a nun longer than she has. I have done a three-year retreat, but she hasn’t.” Watch out for this type of attitude. Of course, a person who has all the qualities and can expound all the teachings properly is very important. But also realize that you are in a situation where any knowledge is appreciated. Until you meet this “perfect” teacher, try to learn wherever and whenever you can. If it is knowledge you are looking for, you will find it. People will be available to teach you, but you may lack the humility needed to be a perfect recipient.

I believe Buddhism will be Westernized. Some changes definitely need to come about, but they need to be well thought out. It is not appropriate to change something simply because we have difficulty with it. Our ego finds difficulty with almost everything! We must examine what will enable people to be more flexible, to communicate better, and to extend themselves to others, and then make changes for these reasons. Deciding what and how to change is a delicate matter and can be very tricky. We must work carefully on this and be sure to preserve the authenticity of the Dharma and keep true compassion at heart.

The need for community

We in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition often become absorbed in “my vows,” “my community,” “my sect,” “my practice,” and this keeps us from putting our practice into action. As practitioners, we should not become isolated from one another. Remember that we are not practicing and are not ordained for our own convenience; we are following the path toward enlightenment and working for the benefit of all sentient beings. Being a sangha member is a hard, yet valuable responsibility. For us to make progress and our aspirations to bear fruit, we must work together and appreciate one another honestly. Therefore, we need to know one another, live together, and experience community life.

We need places where Western nuns can live and practice, just as in the East. If we sincerely want the female sangha to flourish and develop, some amount of hard work is necessary. We cannot simply let it be and say it is difficult. If problems exist, we are, more or less, responsible for them. On the other hand, good results come from working together and being unified. In Western society, you become independent at a very young age. You have privacy and can do whatever you like. Community life in the sangha immediately confronts you with living with different people who have varying opinions and views. Of course problems will arise. Instead of complaining or avoiding your responsibility when this happens, you need to bring your practice to the situation.

Constructing a place for the sangha is not too difficult, but developing trust is. When someone disciplines you, you should be able to accept it. If you want to move out the moment that you do not like something, your life as a nun will be difficult. If you think about giving back your vows every time your teacher or someone in the monastery says something you do not want to hear, how will you progress? The motivation begins with you. You must begin with a solid, sincere motivation and want to follow a path of renunciation. When you have that motivation, problems will not seem so big, and you will meet teachers and receive teachings without much difficulty.

Simply waking up as a community, walking into the shrine room as a community, practicing as a community, eating as a community is wonderful. This must be learned and practiced. The experience of living together is very different from understanding a nun’s life by reading books. A teacher can say, “Vinaya says to do this and not that,” and people will take notes and review the teaching. But this is not the same as living the teachings together with other people. When we actually live it ourselves, a more natural way of learning occurs.

As a sangha, we need to work together. It is important for us to help each other and to help those in positions of responsibility in whatever way we can. We also need to respect those who teach us. When a nun is well trained, she can teach other nuns. The nuns who study with her will respect her, saying, “She is my teacher.” She is not necessarily their root teacher, but she has good qualities and has given them knowledge, and that is reason enough to respect her.

See that in your lifetime, you give whatever you know to at least ten people. Receiving complete teachings is difficult, so when you are fortunate enough to receive teachings, make sure to make it easier for others to get them. Help to improve the circumstances and to share what you learn so that others do not have to struggle as much as you did. When many instructions and teachings are given, we will have educated nuns who are well versed, and they will benefit many people.

The importance of motivation

Whether one is a nun, a Westerner, a Tibetan, a lay person, a meditator, or whatever, practice comes back to one thing: checking oneself. Time and time again, we need to observe very carefully what we are doing. If we find ourselves simply seeing our Dharma practice as an extracurricular activity, similar to a hobby, then we are off track.

Almost all human beings begin with good motivation. They do not begin to practice Dharma with a lack of faith or a lack of compassion. As people continue to practice, some meet favorable conditions and increase their good qualities. They gain genuine experiences through their meditation and grasp the real meaning of Dharma practice. But some who begin with inspiration, faith, and strong motivation, find after many years that they have not changed much. They have the same thoughts, difficulties, and problems as before. They appreciate and agree with the Dharma, but when it comes to practicing it and changing themselves, they find difficulties. Their own ego, anger, laziness, and other negative emotions become so important and necessary for them. Their minds make difficult circumstances seem very real, and then they say they can’t practice.

If this happens to us, we have to examine: How much do we really want enlightenment? How much do we want to go beyond our negative emotions and wrong views? Looking carefully into ourselves, we may see that we want enlightenment, but we also want many other things. We want to enjoy pleasure, we want others to think that we are enlightened, we want them to recognize how kind and helpful we are. From morning to night we encounter samsara, with all its difficulties, at very close range. Yet how many of us actually want to go beyond this and leave samsara?

Genuine great compassion motivates us to attain enlightenment and benefit sentient beings. Nevertheless, we tend to use compassion and bodhicitta as excuses to indulge in what we like. Sometimes we do what ego wants, saying, “I’m doing it for the sake of others.” Other times we use the excuse that we have to do our Dharma practices in order to shirk our responsibilities. But Dharma practice is not about running away from responsibilities. Instead, we need to turn away from habitual negative patterns of thought and behavior, and to discover these patterns we need to look within ourselves. Until that is done, simply speaking about the Dharma, teaching, or memorizing texts does not bring much real benefit.

You talk about compassion and benefiting sentient beings, but it must begin this moment, with the person sitting next to you, with your community. If you cannot endure a person in the room, what kind of practitioner does that make you? You should listen to teachings and put them into practice so that you change.

Faith is an essential element on the path of renunciation, on the path to enlightenment. Our faith is still comparatively superficial and therefore shakable. Small situations make us doubt the Dharma and the path, causing our determination to decline. If our motivation and faith are shakable, how can we talk about leaving behind all the karma and negative emotions that have been following us for lifetimes? Through study and practice we will begin to develop real knowledge and understanding. We will see how true the Dharma is, and then our faith will be unshakable.

In the West, people often want teachings that are enjoyable to listen to, ones which say what they want to hear. They want the teacher to be entertaining and tell amusing stories that make them laugh. Or Westerners want the highest teachings: Atiyoga, Dzogchen, Mahamudra, and Tantric initiations. People flood to these teachings. Of course, they are important, but if you do not have a strong foundation, you will not understand them, and the benefit that they are supposed to bring will not be achieved. On the other hand, when the foundation practices—refuge, karma, bodhicitta, and so forth—are taught, people often think, “I’ve heard that before so many times. Why don’t these teachers say something new and interesting?” Such an attitude is a hindrance to your practice. You have to focus on changing your daily attitudes and behavior. If you cannot do basic practices, such as abandoning the ten negative actions, and practice the ten virtuous ones, talking about Mahamudra will bring little benefit.

Three activities are necessary. Any particular time of your life can contain all three but in terms of emphasis: first, listen to, study, and learn the teachings; second, think and reflect upon them; and third, meditate and put them into practice. Then, with a motivation to benefit others, share the teachings to the best of your capability with those who are interested and who can benefit from them.