Colors of the Dharma

Colors of the Dharma

Report on the 4th Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering, held at Shasta Abbey in Mount Shasta, California, October 17-20, 1997.

Four years ago, some nuns from the Tibetan tradition were musing how wonderful it would be to have Western monastics from the various Buddhist traditions in the USA meet together. Thus was born a series of annual conferences. All were interesting, but the fourth, which was held Oct 17-20, 1997, at Shasta Abbey, CA, was special. Shasta Abbey is a community of 30-35 monastics, established by Reverend Master Jiyu in the early 70s. A bhikshuni, she trained in Soto Zen, so her disciples follow the Zen teachings and are celibate. They were very welcoming, and my overwhelming feeling at our first meal together was how wonderful it was to sit in a room filled with “altruistic closely-shaven ones,” as my friend calls us. I didn’t need to explain what my life is about to these people; they understood.

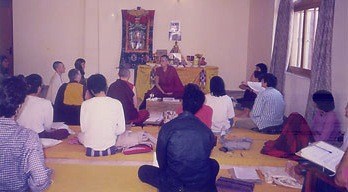

There were twenty participants, Western monastics from the Theravada, Tibetan, Soto Zen, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean traditions. The collage of colors was beautiful. The theme of our time together was “training,” and each session a monastic gave a brief presentation that sparked a discussion. I won’t pretend that this is a complete or impartial view of the conference. Shared below are some of the points that sparked my interest the most. The first evening we had introductions, a welcome session, prayers and meditation, and a tour of the abbey. All of us were amazed at what the community has created together. Many of the monastics have been there for over 20 years, a kind of stability seldom seen anywhere in America these days. Clearly, the monastic life and that community were working for them.

Saturday morning Reverend Eko, the abbot of Shasta Abbey since Reverend Jiyu’s passing last year, talked about their training. A monastery is a religious family. It’s not a business, a school, or a group of individuals competing with or knocking into each other. The reason one goes to a monastery is to be a monastic, so learning, practice and meditation are foremost. A second reason is to be part of a community. Community life itself is our practice because living with others puts us right up in front of ourselves. We keep bumping into our own prejudices, judgements, attachments and opinions and have to own them and let them go, instead of blaming others. Novice training focuses on helping us become more flexible and give up clinging to our opinions and insisting that things be done how we want them to. Too much formality in the training makes us stiff, too little and we lose the sense of gratitude and respect so important for progress. A third reason for going to a monastery is to offer service to others, but with care not to reify our service into an ego-identity of “my work” or “my career.”

Venerable Tenzin Kacho, a bhikshuni in the Tibetan tradition, talked about teacher training. I noticed that those monastics who were just beginning to teach were concerned with learning teaching techniques in order to give clear talks. But for those who have been teaching for some time, the issue was how to be a good spiritual guide and how to work with students’ lack of appreciation or negative projections. Years ago, Ajahn Chah said that if we try to please our students, we will fail as teachers. A teacher’s duty is to say and do what is beneficial for the student, not what will make him or her well-liked or attract a lot of people. Especially, as monastics, we shouldn’t depend on having students. We don’t need to draw a crowd in order to get sufficient dana to support a family. We live simply, and our purpose is to practice, not to please students, become famous or establish big Dharma centers. As a teacher, we should be like a garbage pit: students will dump their rubbish on us, but if we accept it without hurt or blame, then it decomposes and the pit never fills up. Because sentient beings’ minds are untamed, it is not unusual for them to misinterpret their teachers’ actions and project faults on their teachers. When students have problems with their teacher, we can refer them to another teacher or member of the monastic community to help them at that time. Reverend Jiyu said that having students could be the “biggest grief.” At the end of the conference, I asked one junior member what touched him the most that weekend. He said it was hearing his own teachers say how difficult it was when they tried to help students, and the students, their buttons pushed, got angry in return. “It made me stop and think,” he said, “When have I done that to them?”

That evening I spoke about thought training, emphasizing the “taking and giving” meditation and ways to transform adverse circumstances into the path. Taking and giving is a turnabout from our usual attitude, for here we develop compassion that wishes to take others’ suffering onto ourselves and love wishing to give others all of our own happiness. Then we imagine doing just that. Of course, the question arose, “What happens if I do that, get sick and then can’t practice?” This led into a lively discussion about our multiple layers of self-centeredness and our rigid concept of self. Giving all the blame to the self-centered thought is a way to transform adverse circumstances into the path, because we experience adversity due to the negative karma we created in the past under the influence of self-centeredness. Therefore, recognizing that this self-preoccupation is not the intrinsic nature of our mind but an adventitious attitude, it is only fitting to blame it, not other sentient beings, for our problems. I shared with them the time I offered to help a fellow practitioner and he told me off instead. For once, I remembered this way of thinking and gave all the pain to my self-centered attitude. The more he criticized, the more I passed it on to the self-centeredness, which is my real enemy, the actual source of my suffering. At the end, atypical for me, my mind was actually happy, not in turmoil, after being cut apart.

Sunday morning Ajahn Amaro from the Thai forest tradition spoke on Vinaya training (monastic discipline). “What is living in precepts all about? Why was our teacher, the Buddha, a monk?” he asked. When the mind is enlightened, living a life of non-harmfulness—that is, living according to the precepts—automatically follows. It’s the natural expression of an enlightened mind. The Vinaya is how we would behave if we were enlightened. Initially when the Buddha first formed the sangha, there were no precepts. He set up the various precepts in response to one monastic or another acting in an unenlightened way. Although the precepts are many, they boil down to wisdom and mindfulness. The Vinaya helps us establish our relationship to the sense world and live simply. The precepts make us ask ourselves, “Do I really need this? Can I be happy without that?” and thus steer us towards independence. They also heighten our mindfulness, for when we transgress them, we ask ourselves, “What in me didn’t notice or care about what I was doing?”

The Vinaya makes all the monastics equal: everyone, regardless of his or her previous social status or current level of realization, dresses the same, eats the same, keeps the same precepts. On the other hand, there are times when one person or another is respected. For example, we heed the Dharma advice of our seniors (those ordained before us), no matter their level of learning or realization. Serving the elders is to benefit the juniors—so they can learn selfless behavior—not to make the seniors more comfortable. In other situations, we follow whoever is in charge of a certain work, regardless of how long that person has been ordained.

When someone—a friend, student or even teacher—acts inappropriately, how do we deal with it? In a monastic community we have a responsibility to help each other. We point out others’ mistakes not to make them change so that we will be happier, but to help them grow and reveal their Buddha nature. To admonish someone, the Vinaya gives us five guidelines: 1) ask for the other’s permission, 2) wait for an appropriate time and place, 3) speak according to the facts, not hearsay, 4) be motivated by loving-kindness, and 5) be free of the same fault yourself.

Saturday afternoon was “robes around the world,” a veritable Buddhist fashion show. Each tradition in turn showed their various robes, explained their symbolism, and demonstrated the intricacies of getting them on (and keeping them on!). Several people later told me that this was a highlight of the conference for them: it was the physical demonstration of the unity of the various traditions. At first glance, our robes look different: maroon, ochre, black, brown, gray, orange, various lengths and widths. But when we looked closer at the way the robes were sewn, we found that each tradition had the three essential robes and each robe was made of the same number of strips stitched together.

Patches of cloth stitched together are the symbol of a simple life, a life in which one is willing to give up the immediate pleasures of the external world in order to develop inner peace and ultimately in order to benefit others. This is the quality I noticed in the people present at the conference. No one was trying to be a big teacher, make a name for themselves, set up a big organization of which they were head. No one was complaining about their teachers or anyone else’s teachers. No, these people were just doing their practice, day after day. There was a quality of transparency about them: they could talk about their weaknesses and failures and not feel vulnerable. I could see that the Dharma worked. There were qualities about those who had been ordained for twenty years that aren’t found in the average person, or even in the newly-ordained. These people had a unique level of acceptance of themselves and others, a certain long-range vision, constancy and commitment.

Sunday evening we discussed the student-teacher relationship and how it fits in our practice. One monk said that he sought out his teacher because he wanted help to do what he knew needed to be done in the spiritual path. At first there seemed to be a big difference in the importance of the teacher-student relationship and the way it was to be cultivated and used in the practice of each tradition. However, thinking about it more, a unity emerged: our teachers recognize a far greater potential in us than we see in ourselves, and they challenge us to the core in order to help us bring this out. A Theravada monk told the story of a Western monk who was upset with Ajahn Chah and went to tell him his mistakes. As the student railed on and on about Ajahn’s faults, Ajahn Chah listened intently, and at the end said, “It’s a good thing that I’m not perfect, otherwise you’d think enlightenment was somewhere outside yourself.” A Zen monastic said that whenever a student started to idolize Reverend Master Jiyu and become too dependent, she would start clicking her false teeth around in her mouth while they had tea. A Tibetan nun told of Zopa Rinpoche keeping his students up until the wee hours, teaching on and on, while they struggled either to stay awake or to deal with their anger at having to do something virtuous for so long when they wanted to go to sleep. When the teacher is wise and compassionate, and the student is aware, sincere and intelligent, life itself becomes the teaching.

Each evening, post-session discussions lasted into the night. There was a genuine thirst to learn more about each other’s practices and experiences and to use that knowledge to enhance our own. As Monday morning came, everyone felt a deep sense of appreciation at the dependently-arising event we had shared in and strong faith and gratitude for the Buddha, our common teacher. After meditation and prayers, we met together and each monastic said a dedication from his or her heart, and then the winds of karma blew the leaves in different directions as we parted.

To be on the mailing list for future conferences, please contact Ven. Drimay, Vajrapani Institute, Box 2130, Boulder Creek CA 95006.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.