Introduction to the lamrim teachings

Qualities of the compilers and teachings

Part of a series of teachings based on the The Gradual Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim) given at Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle, Washington, from 1991-1994.

Introduction to the lamrim

- Introduction

- Approach

- Integration into our lives

- Long-term view towards enlightenment

- Structure of the teaching sessions

- Vajrayana flavor in the lamrim

- Overall outline

LR 001: Introduction (download)

Qualities of the compilers

- Lineage of the teachings

- Spread of the teachings

LR 001: Qualities of the compilers (download)

Qualities of the teachings

- Teachings according to Atisha’s Lamp of the Path

- Teachings according to Lama Tsongkhapa’s Great Exposition on the Gradual Path to Enlightenment

- What teachings to practice

LR 001: Qualities of the teachings (download)

Meditating on the lamrim

- Review

- How to do analytical meditation on these topics

LR 001: Review (download)

Questions and answers

- The only path

- Practitioners corrupting pure teachings

- Humility in the teacher

- Finding the perfect people

- Action and motivation

- The precept of not killing

LR 001: Q&A (download)

Introduction and class structure

First, I think we are all very fortunate to be able to have this time to be together and to talk and learn about the Buddha’s teachings. We are very fortunate just to have this opportunity to hear the Buddha’s teachings in our world. It shows that somehow we have a lot of good karmic imprints in our mindstream. We’ve probably all done something virtuous together before. This karma is now ripening together in us having this opportunity to again create more good karma and make our lives meaningful. This is really something to rejoice over.

The class will be on Monday and Wednesday evenings at 7:30 promptly. I ask people to register for the class with the idea that people will feel committed to coming. The class is designed for people who truly want to learn the lamrim and have a commitment to practicing the Buddha’s teachings in their own lives. If you participate in this series of teachings, please come every time. It’s for everybody’s benefit and also so that we have a cohesive group energy.

At the science conference in Dharamsala last year, there was one guy who had a PhD. He was running a stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts. People who were referred to him by doctors for health problems had to sign up for an eight-week course. They came 21-22 hours every week without fail. Six days a week they had to meditate for 45 minutes. Once during that eight weeks they had to come for a whole day and keep silence. He was teaching them Buddhist meditation without the label “Buddhist” to treat their health problems. These were people who weren’t even Dharma practitioners, but they signed up and they did it.

Feeling bolstered by what he did, and since people who are coming here already have some kind of commitment to the Dharma, I am asking you to please do some meditation in the morning every day for at least 20 minutes or half an hour. The purpose of this, again, is to bring a consistent practice to your lives. Doing something daily is really important if you are going to get anywhere. Also, because you are going to be receiving teachings, you’ll have to set aside time to think about them. If you just come here and then go home and don’t think about the teachings, you don’t derive the real richness and benefit.

So, I am asking you to please—at least once a day, more if you can—do a 20-minute to half-an-hour session. You can do the prayers we just did, followed by a few minutes of breathing meditation to calm the mind down. Then do analytic meditation—sit and think about the various points that we discussed in the most recent teachings.

One reason why you have an outline here is so you’ll know where we are going together and you can follow when I speak, and also so that you’ll have the essential points already written down, which will make your meditation much easier.

If you look at the outline, the first page says “Overview of the Lamrim Outline.” This contains the main themes of the entire path. When you look at page 2, it says the “Detailed Lamrim Outline.” This is an expanded version of the lamrim outline on page 1. This will be the outline that we’re basically following during the teachings and during your meditation sessions. You can think about each subject point by point, recalling what you heard, and check it logically to see if whatever was explained makes sense. Look at it in terms of your own life and your own experience.

This outline is based on the outline of the Lamrim Chen Mo, (The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path). There are several different lamrim texts. This is a very general outline that corresponds roughly to all of them in terms of the essential points.

Approach

I want to give the teachings in the traditional way, in the sense of going through the lamrim outline step by step. When I was here last time, many people commented to me that they’ve heard fragments of teachings here and there, and many different things, but they didn’t know how to put them together into a step-by-step sequential path—what to practice and how to do it. This teaching is designed to help you put together all the different teachings that you have heard so that you know what is at the beginning of the path, what is in the middle, what is at the end, and how to progress through it.

It’s traditional in the sense that I am going to present it more or less in the form that is given to the Tibetans. I will be going through all the different points, and these include a lot of things that we may consider to be part of Tibetan or Indian culture, or things that our minds might feel quite resistant about. But I want to go through these points with the idea of giving you a Western approach to understanding them. You might take more extensive teachings from some of the Tibetan lamas later on, and if I am able to at least introduce you to some of those topics through the Westernized approach, then when you hear the standard Tibetan approach, it will go in more smoothly for you, like when they talk about the hell realms and things like that.

Integration into our lives

At the end of each session, I want our discussions to focus on how we’ve integrated those points in our own 20th-century American life, what other points we would add to it, or how we, as Westerners, should look at certain points. I want us not to feel like we have to become Tibetans and not to feel like we have to swallow everything hook, line, and sinker. Rather, we want to use our creative intelligence and examine the teachings logically, according to our experience, and try to integrate them. At the same time, we also want to be very clear about which points we as individuals have difficulty with so that we can help each other seek ways to understand those points.

I am saying this because I am thinking of one of my teachers. He went to teach in Italy where I heard he spent about two days talking about the suffering of the hell realms. The people there were going, “Wait a minute. This is summer in Italy. I didn’t come on my vacation to hear about this.” [Laughter] How are we as Westerners going to view these kinds of teachings, and what baggage from our Christian upbringing are we bringing in to these subjects? Similarly, when we talk about love and compassion, are we seeing it through our Judeo-Christian eyes, or can we really understand what the Buddha is getting at? What’s the difference between how we were brought up and the Buddha’s approach? What are the similar points? I want us to think about all these things in our mind as we start to look at all of our preconceptions, all of our habitual ways of interpreting things.

Long-term view towards enlightenment

This series of teachings is designed for people who are serious in the practice. It’s designed for people who want to attain enlightenment.

It’s not designed for people who just want to learn some way to deal with your anger. You can go through these teachings and you’ll get some techniques on how to deal with your anger, and how to deal with your attachment. These definitely will come out in the teachings, but that’s not the only point.

We are going to go more in depth. We really have to have a long-term view. Everything is being explained to us in the context of us actually becoming a buddha and us actually stepping onto that path and practicing that path to become a fully enlightened buddha.

There is only one point where I am going to stop and give a lot of background information. The Tibetans say that this text, The Gradual Path (which is what lamrim means), is for beginners, and it takes you step by step from the beginning to the end. However, the teaching also presupposes a whole world view behind it. If you’re brought up Tibetan, Chinese, or Indian, you would have this world view. If you’re brought up an American, you don’t. For example, the world view of multiple births—that we are not just the person we are in this body, the idea of karma—cause and effect, the idea of different life forms existing not only on our planet earth but also other universes. I will, in the early lectures, set aside a whole lecture to talk about those issues, to fill us in on all the things that are supposed to take place before starting lamrim.

Structure of teaching sessions

We will continue the sessions as we did today. Some prayers at the beginning, then silent meditation for 10-15 minutes, and then I will talk for maybe 45 minutes or an hour, and then we’ll have questions and answers and discussion. When you go home, you can contemplate and review the different subjects we’ve talked about. At the next session, during the question-and-answer and discussion time, you can bring up some of the reflections that you’ve had and your understandings through meditation.

Vajrayana flavor in the lamrim

Although it is said lamrim is designed for beginners, in actual fact, I think that the lamrim is set out for somebody who already has the idea that they want to practice Vajrayana. You will find a certain Vajrayana flavor throughout the whole text, starting from the very beginning. And even though the different topics are presented serially—first you do this, then you do that, then you do this—in actual fact, you will find that the more you understand the later topics, the easier it is to understand the beginning ones. Of course, the more you understand the beginning, the easier it is to understand the later sessions. Even though they’re presented step-by-step, they interweave a lot. For example, the meditation on our precious human life comes earlier in the path. However, the more we understand the altruistic intention, which comes in the later part of the path, the more we’ll appreciate our precious human life and the opportunity we have to develop that altruistic intention. As with all these meditations, the more you understand one, the more it will help you to understand the others.

Because it has this tantric influence right from the beginning, your mind is already beginning to get some imprint of the tantra. Something’s starting to sink in about that whole way of viewing things. This is actually quite good. For example, right from the beginning, when I get into the part describing the prayers, we will be learning about visualization and purification. You do a lot of visualization and purification after you’ve taken initiations and do the tantric practice. However, just in our basic Dharma practice here, we are already doing those same things. It’s making some familiarity with that in our mind, which is very beneficial for us.

Overall outline of lamrim

The lamrim outline has four major sections:

- The preeminent qualities of the compilers, in other words, the people who established this system of teachings. You look at their qualities and gain respect for them and what they have done.

- The preeminent qualities of the teachings themselves. You get some kind of excitement about everything you can learn by practicing these teachings.

- How these teachings are to be studied and taught. We get an idea of how we should be working together

- How to actually lead somebody on the path. Most of the text is involved in this fourth point, how to actually lead.

Pre-eminent qualities of the compilers

Lineage of the teachings

Let’s go back to the first major section: the preeminent qualities of the compilers. This is basically just giving you a little bit of the historical perspective, knowing that the teachings came from Shakyamuni Buddha. I am not going to tell you too much about Buddha’s life because I think you can read a lot about that.

But what is interesting about the Buddha’s life is that even though he lived 2,500 years ago in India, his life is very much like middle class American life in the sense that he grew up in the palace with all the pleasures of the world. The ghetto, the neighborhoods where they have the shootings, were far away. His father wouldn’t let him go there. He was locked inside a palace and he only had nice things. All the aged people, the decrepit people, the poor people, the sick people—they were all in another part of town. The idea is we don’t see them. The insane people, the mentally impaired people, all the unpleasant things—we kind of push away. We go through our fantastic middle class life going to the movies, going to the shopping malls, going on the sail boats, going on vacations, and live very pleasurable lives. This is exactly how the Buddha lived too.

One day, he went out of the palace. He sneaked out on four different occasions. One time, he saw an old person. The Buddha was quite shaken up and he asked his charioteer, “What’s going on here?” The charioteer said, “Well, this happens to everybody.” This is kind of like us when our parents start to get old. We watch our parents aging and how it’s disturbing to us.

The second time the Buddha went out, he saw a sick person. Again, he was shocked when he learned this happens to everybody. It’s like us when we get very sick or when one of our friends dies. They are not supposed to die. Not when they are young anyway. And yet it happens. It jars us. That’s similar to what the Buddha experienced.

The third time he went out, he saw a corpse. Again, he learned that death happens to all of us. This is like when somebody we’re close to dies and we go to the funeral. Of course the Buddha saw a corpse as it is, whereas we go and we see it looking so beautiful—nice rosy cheeks and peaceful smile—all made up. But still, in spite of how they try to cover up death, it’s a shocking experience for us. It makes us look back at our own life and question, “What is the purpose of my life? What am I going to have to take with me when I die?”

The last time the Buddha went out, he saw a religious person, a wandering mendicant, one who had given up the whole middle class life or palace splendors to devote oneself to the practice of making life meaningful for others. This is kind of where we are at right now. All of us are coming to the teachings, having had some experience of sickness, old age, and death. We feel a lot of dissatisfaction, frustration, and anxiety. We are at the point now where we are looking to find something different, something that is going to put our life together. That’s the point the Buddha reached.

The Buddha left the palace, cut off his hair, and put on robes. I am not encouraging you people to do that now, although I have my hair clippers, if anybody wants them. [Laughter] That’s not the point—to change the hair-do and clothes. The point is to change the mind. I think we are similarly at that threshold in our mental development of “We want to change the mind and find something else.”

What the Buddha did is he left that whole middle class life. He did a little bit of spiritual supermarket shopping too. He went to various teachers and practiced their teachings. It’s like us going to Hare Krishna, to karma therapy, to past life regression. We do our spiritual supermarket shopping too. The Buddha did the same. He even went to the point of extreme asceticism, they say eating only one grain of rice a day. He got so thin that they say he could touch his backbone when he touched his belly button. He realized that severe asceticism wasn’t the way to enlightenment. Spiritual practice is more a thing of purifying the mind, not so much the body. It’s good to eat health foods, but eating health foods alone won’t make you a buddha. It has to be the mind. At that point he started eating again. Getting strong, he went and sat under the bodhi tree and through very deep meditation, he perfected his wisdom and compassion. When he arose from that meditation session, he was a fully enlightened buddha. At the beginning, he didn’t want to teach anybody. He didn’t think that people would understand. But then different celestial beings from the god realms as well as different human beings came and requested him for teachings.

Gradually, he began to teach and people began to benefit a lot from his teachings. When Buddha gave his first teaching, he only had five disciples. Five people. The Buddha started with five, and look what happened! Those five got realizations, went out and spread the teachings to others who also got realizations. They in turn spread the teachings to others. Soon enough it began a major world religion. Start small with a lot of quality, we can get somewhere. This is a very good example.

Buddha spent 45 years going around India teaching. Now, as he went from place to place, he gave a lot of different talks to different groups of people. He didn’t teach everything exactly in the order that is presented in the lamrim. When he talked with educated people, he spoke one way. When he talked with people with a lot of good karma, he spoke one way. When he talked to people with very little good karma, he explained things in a much simpler manner. He gave a lot of different teachings to different kinds of audiences. And then, later, what happened is the major points from all these various teachings, given over time to a wide range of different audiences, got drawn out and systematized into what’s called the lamrim, the gradual path.

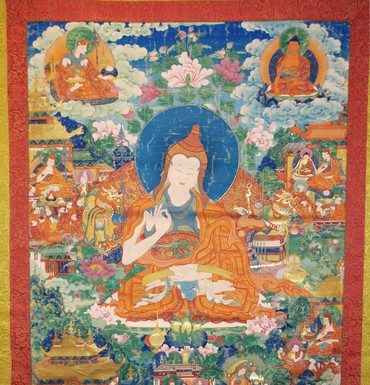

It was Lama Atisha, an Indian practitioner of the 10th or 11th century, who drew out the major points and systematized them. Later on in Tibet, Lama Tsongkhapa, who lived in the late 14th, early 15th century, explained everything in much more depth.

Spread of the teachings

Buddha’s teachings were initially not written down. They were passed down in an oral tradition. The people memorized them and passed them down. Around the first century B.C. it began to be written down. Throughout this time, as Buddhism spread through India and then down south into Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), there were very learned practitioners, which led to the development of commentaries on the Buddhist texts and different systematizations of the Buddha’s teachings.

There were great Indian scholars and practitioners (they’re called pundits) such as Asanga, Vasubandu, Nagarjuna, and Chandrakirti—you will hear all these names mentioned more often as you get into the teachings.

There were also different philosophical schools. People extracted particular points in the Buddha’s teachings and really emphasized those and interpreted them in a certain way. There was also a system of debate. The Buddhists were always debating each other. The Buddhists never had one party line that everybody bought. There was never fear of excommunication if you didn’t buy that party line.

Right from the beginning, there were different traditions developing because people interpret things in different ways. They draw out different points to emphasize and they debate on them.

I think debating is very, very good. It makes our mind sharp. If there were a dogma that we just had to hear and believe in, our intelligence would cease to function. But because there are all these different viewpoints, then we have to think, “Oh, what’s right?” “How does this work?” “What do I really believe?” There was this whole system of debate going on throughout ancient India.

The teachings spread south into Ceylon, Thailand, South East Asia, China. From China it spread into Korea, Japan, and into Tibet in the seventh century. The Tibetans actually have the most extensive Buddhist canon, the most extensive collection of Buddhist teachings, including not only the texts on discipline (the Vinaya) and the Mahayana texts which describe the bodhisattva path of developing love and compassion, but also the Vajrayana or tantric texts, a special method with which we can progress along the path very quickly if we’re properly prepared. There they were written down and commented on, and they were preserved for centuries.

Then, due to the invasion of Tibet by China, the Tibetans left Tibet and the world was able to learn the Tibetan teachings. Tibet had been isolated for centuries—difficult to get in and difficult to get out. They have their own insular religious community, but since 1959, when there was the abortive uprising and thousands of people fled to India, the Tibetan teachings became more widespread in Western countries. We are very fortunate in this way.

The preeminent qualities of the gradual path teachings as presented in Atisha’s Lamp of the Path

We go on now to talk about the preeminent qualities of the gradual path teachings, specifically in relationship to Atisha’s systematization of the Buddha’s teachings in his text called Lamp of the Path to Enlightenment.

All the doctrines of the Buddha are non-contradictory

One of the benefits of this way of extracting the major points and ordering them is we come to see that none of the Buddha’s teachings are contradictory. If we don’t have this systematization, and if we don’t understand what we’re supposed to practice at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end, then when we hear different teachings, we might get very confused because they seem contradictory.

For example, at one point you might hear that our precious human life is really important, our human body is really a great gift. We need to protect the body, it’s the basis for our whole practice of Dharma, we’re so fortunate to have a body. Then you hear another teaching that says this human body is a bag of pus and blood. There’s nothing to be attached to, there’s nothing great about it. We have to completely give it up and aspire for liberation. If in your mind you don’t have an overall view of the path to enlightenment and where these two thoughts fit in, you are going to say, “What is going on here? These are two completely contradictory things. You are telling me the human body is great, and then you are telling me it’s a bag of junk. What’s the story?”

But if you have this overall view, then you can see that for the purpose of encouraging us to practice through recognizing our very fortunate opportunity, we think of the advantages of our human body and this human life. However, later on in the path, when our mind is more developed, then we will see that even though this body gives us a certain fortune to practice, it is not an end in itself. The real end is liberation. And to achieve liberation, we have to give up clinging to things that don’t bring ultimate happiness, for example our body.

Another example is pertaining to eating meat. This is a real hot topic in Western Dharma centers because when the Theravada monks come, they eat meat. The Chinese monks come, and no meat. Then the Tibetan monks come and you can have all the meat you want. You think, “Do you eat meat as a Buddhist, or don’t you eat meat as a Buddhist? What’s going on?” Now, that depends very much on your level of practice.

In the Theravada tradition, they emphasize very much the idea of detachment. Detachment is actually emphasized in all the Buddhist teachings, but it’s explained in slightly different ways in different traditions. In the Theravada tradition, it means you are content with whatever you have. And the way they practice that contentment or detachment is they go from door to door to collect alms each day. Those of you who have been to Thailand, you remember seeing the monks go door to door and the laypeople putting food in the bowl. Now, if you are a monk going door to door and you decide you are vegetarian, then you’ll have to say, “Sorry I don’t want that food, but give me some asparagus over there.” “No eggs, please.” “Give me the peanut butter.” That is not conducive for developing a contented, detached mind.

So in the Theravada teachings, you were allowed to accept meat, provided that it hasn’t been killed for you, you didn’t kill it yourself, or you didn’t ask anybody else to kill it. Barring those three exceptions, you are allowed to accept meat for the purpose of developing this detached mind that is not choosy and picky.

At a later level of the practice, you get into all the teachings about love and compassion and altruism. And there you are saying it’s fine to be detached. But what is really important in the practice is to have love and compassion for others. If we’re killing animals to feed ourselves, we are not really respecting their lives. We are not really having compassion for them. Therefore we practice vegetarianism. At that level of the path, you give up eating meat, you become vegetarian.

Then, you go on into the tantric level of the path, and there, on the basis of detachment, on the basis of altruism and compassion, you start doing very technical meditations, working with the subtle energies of your body in order to realize emptiness or reality. Now, to do those meditations with the subtle energies, your body needs to be very strong. You need to eat meat to nourish particular constituent elements in your body that aid your meditation. You meditate for the benefit of others. At that level of the path, you are allowed to eat meat again. It is not at all contradictory if you have this understanding of the gradual path. You practice different things at different times.

In that way we can see how the different practices of the different traditions fit together and you develop respect for all of them without being confused.

All the teachings can be taken as personal advice

The second point is that the systematization of the lamrim shows us how all the teachings can be taken as personal advice. In other words, all the teachings that we hear, we will be able to put them together. It’s like having a kitchen with a flower canister, a sugar canister, and another for honey or oatmeal. When you buy something in the market, you know where the canister belongs and you know how to use it. Similarly, if we’re familiar with the step-by-step progression of the path, then if you go hear a lecture by this teacher or from that teacher, you’ll know exactly where on the path that subject matter is. You won’t get confused. In the Burmese tradition, they talk about vipassana and samatha. “I know where that fits on the path. I know what elements they’re emphasizing.” Similarly, if you go and listen to a teaching by a Chinese master or a Zen master, you will know where that teaching fits on the path.

You will be able to take all of these different teachings that you are hearing and use them in your own practice. You’ll see that they are all meant as personal advice according to what level of the path you are on. One of the big problems in the West is that you hear a little bit here, and a little bit there, and a little bit here, and a little bit there, and nobody knows how to put them together. The real advantage of going through everything step-by-step is you get a whole overall view and know where each topic belongs. This is really, really helpful.

Also, another way in which you begin to see things as personal advice is that you recognize that we shouldn’t make a split between intellectual studies and meditation. In other words, some people say, “Oh, this text is just intellectual. It’s not so important. I don’t need to know that material.” That’s not very wise. If we understand the step-by-step progression and all the different qualities we need to develop in our mental continuum to become a buddha, we will realize that the way to develop these qualities are taught in those texts. Those texts are actually giving us the information which we need to put into practice in our daily life. Again this is really, really helpful. You don’t go to a teaching and say, “Oh, they are just talking about five categories of this and seven categories of that. It’s not for meditation. I am bored.” Rather, you begin to realize, “Oh, the five categories of this, this belongs to this step on the path. It’s designed to help me develop these qualities in my mind.” You’ll know how to put it into practice.

The ultimate intention of the Buddha will easily be found

Then the third benefit is that we begin to understand what the Buddha’s intention is. His overall intention is, of course, to lead all beings to enlightenment. But we will be able to also draw out the important points, the specific intention in the teachings. We begin to see what the gist of the teachings is all about. Again, this is very difficult to do.

I was teaching in Singapore for a while. The people there, by and large, haven’t heard the lamrim teachings. They get some teachings from the Sri Lankans, some teachings from the Chinese, from the Japanese, from the Thai, and then they go, “I am lost. What do I practice? Do I chant Namo Ami To Fo? Or do I sit down and do breathing meditation? Or should I pray to be born in the pure land? Should I try to become enlightened in this lifetime?” They get completely confused. They don’t see how all these things fit together on the path and they are not able to draw out the important points of all these different teachings and put them in a way that makes sense. I saw that even though I didn’t know very much, I wasn’t confused. That’s because I was taught the systematic approach through the kindness of my teachers. It made me really appreciate the lamrim so much.

It’s really an incredible benefit to have this kind of approach because then we can see what is important and how it all fits together. Otherwise, because the scriptures are so numerous and so vast, we can get lost very easily. Through the kindness of all the lineage teachers, who picked out the important points and put them in an order, it becomes a lot easier for us…

[Teachings lost due to change of tape]

Avoiding the error of sectarian views regarding a Dharma lineage or doctrine

…Being in Singapore, which has many Buddhist traditions, created the need for me to know more about the other traditions in order to help the people who were coming and asking me questions about them. I started learning more about other Buddhist traditions and the more I learn, the more I discover how incredibly skillful the Buddha was.

Incredible by teaching so many different meditation methods, by emphasizing different ways of practice to different groups of people, the Buddha was able to reach out to so many different kinds of people—people of different interests, different dispositions, different ways of understanding things. Seeing all these differences really deepens my respect for the Buddha as an incredibly skillful teacher.

We respect the fact that we all don’t think alike. When we talk to other people, we have to talk according to the way they think, and that’s exactly what the Buddha did. That’s why there are many Buddhist teachings and traditions. He taught according to how they thought so that the teachings became beneficial to them. He didn’t say, “Okay, this is it. Everybody has to think like me.” He wasn’t like that. He was completely sensitive. This is a really good example for us when we talk to our non-Buddhist friends or our Buddhist friends, to be skillful in that way. Find the things in the Buddhist teachings that make sense to that person, that help them.

The preeminent qualities of the gradual path teachings as presented in Lama Tsongkhapa’s Great Exposition on the Gradual Path to Enlightenment

Encompasses the entire lamrim subject matter

Lama Tsongkhapa was born a few centuries after Atisha. He took Atisha’s presentation and added a lot of material to it to round it out and explained a lot of points that before hadn’t been clear. The advantage of that is that it encompassed the whole lamrim, the whole gradual path to enlightenment. The teachings that we are about to receive contain all the essential points of the whole path to enlightenment. This is really nice, isn’t it? It’s like having the great computer manual that covers all the systems, that doesn’t leave anything out.

Easily applicable

In addition, it’s easily applicable because this text is written for meditation. It’s written so that we learn and we think about what we hear and then use it to transform our mind. It is not written for intellectual study. It’s written for us to think about, and in thinking about it, to change our attitude and our life. Meditation isn’t just watching the breath. Meditation is transforming the way we think. It’s transforming our perception of the world. By learning all these different steps on the gradual path, by reflecting on them every morning and every evening, your view of life starts to change. The way you interact with the world starts to change. That’s what meditation is about.

Endowed with the instructions of the two lineages (Manjushri and Maitreya)

The third point is that this presentation of Lama Tsongkhapa has the instructions from the two lineages of Maitreya and Manjushri. The gradual path has two aspects—the method side of the path and the wisdom side of the path. The method side starts out with the determination to be free from our difficulties. It goes on to the development of compassion and altruism. It contains practices such as generosity, ethics, patience—all the activities of a bodhisattva. The wisdom side of the path is helping us to look deeper into the nature of things and how they really exist. We need both sides of the path.

Now, these two sides of the path were emphasized by different lineages of teachings. One lineage of teachings is called the extensive teachings. It deals with the method side of the path and it came down from Maitreya to Asanga and down to the last lineage holder, Trichang Rinpoche. And now His Holiness holds the lineage.

On the wisdom side of the path, it started with Manjushri, Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti, and all those masters who showed us how to meditate on emptiness, and it went down to Ling Rinpoche, and now to His Holiness.

This teaching has the advantage of having both of these lineages of teachings—one emphasizing the practical way of working with compassion in the world, the other emphasizing the wisdom realizing emptiness.

What teachings to practice?

Teachings which have Buddha as the source

We want to practice a teaching that has Buddha as the source. This is really important. Why? Because the Buddha was a fully enlightened being. His mind was completely free of all defilements. He had developed all the good qualities to the full extent. What the Buddha said is reliable because he gained the realizations himself.

Nowadays we have such a spiritual supermarket. Gary got a phone call today telling him about somebody who was coming to Seattle who was enlightened two years ago in Bodhgaya. You have such a spiritual supermarket with all these new traditions of enlightened beings coming up. In The New Times, they were talking about karma therapy and they were talking about a Vesak celebration with some spiritual being going to give a talk. But do any of these people have lineages? Where did all these traditions start? Most of them started right here with that person who’s talking. The question is, is that person’s experience a valid experience or not? Maybe some of them have valid experiences. It’s for us to use our wisdom and judge.

Tried and tested teachings

The nice thing about the Buddhist tradition is you can see that first of all, it started with somebody who is a fully enlightened being. Secondly, it was passed down through a lineage which has been tried and proven for 2,500 years. It didn’t start two years ago. It didn’t start five years ago. It’s something that’s been passed down and it’s been passed down in a very strict way from teacher to disciple. It’s not that the masters dredged something up all of a sudden and interpreted it their own way to spread a new religion. The teachings and the meditation techniques were passed down very strictly from teacher to disciple so that each successive generation was able to have pure teachings and gain realizations.

Being aware of this helps give us a lot of confidence in this method. It isn’t some new ephemeral bubble that somebody developed, wrote a book and went on a talk show about, and made a million dollars selling a bestseller on. It was something that started out with a fully enlightened being who had completely pure ethics, who lived very, very simply, and who, with great compassion, took care of his disciples. They then took care of their disciples and so on down to the present day. It is important to be assured that something has the Buddha as its source, has a tried and true lineage that is tested over many years by the Indian pundits and later by the Tibetan practitioners. It’s now coming to the West.

Teachings practiced by sages

Lastly, practice teachings which have been practiced by sages. In other words, people have gained realizations from the teachings. It isn’t just something that sounds good and exotic. It’s something that people have actually practiced and gained realizations from practicing it.

Review

Let’s review. We talked about the qualities of the lineage, how the teachings started with the Buddha.

By the way, I should add, I received the lamrim teachings from several of my teachers. I received most of the teachings from Lama Zopa, Serkong Rinpoche, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama. I also received teachings from Gen Sonam Rinchen, Kyabje Ling Rinpoche, and Geshe Yeshe Tobten. Whatever they taught me was perfect. Whatever I remember may not be. Please, if you find things that I’m saying mistaken, please come back, and we will discuss them and figure out what is going on. But just to let you know that I have received them somehow, it has been passed down in that way.

We talked about the qualities of the originators of the system and the qualities of the teachings themselves in terms of Atisha’s presentation.

We saw how, if we understand the lamrim, we’ll see that none of the Buddhist teachings are contradictory. We’ll know which practices go with which times. We won’t get confused when we see different people practicing different things. We will be able to see that all the teachings should be taken as personal advice. They are not intellectual knowledge. They are not something to be chaffed aside. They are actually for us to practice. We will be able to pick out the Buddha’s intention, in other words, the important points in all the teachings. We will be able to put them in order systematically no matter what teaching we hear from other sources. We will know where it goes on the path and we won’t get confused. By understanding all of those things, the fourth benefit is that we won’t develop sectarian views, but instead will come to really have a lot of respect for other Buddhist traditions, other lineages and other masters.

With respect to Lama Tsongkhapa’s particular putting together of the lamrim, we see that it contains all of the Buddha’s teachings. It’s nice because we are getting the important points of all of the teachings. We are getting them in a way that’s easily applicable and that’s designed for meditation. It’s complete with information from both the extensive lineage that emphasizes the method and compassion part of the path, and the profound lineage that emphasizes the wisdom part of the path. We are getting complementary teachings put into the lamrim structure from both of those lineages.

How to do analytical meditation on these topics

You might be wondering, “How am I supposed to meditate on this?” Well, hopefully something of what we have said today has sunk in and made you think a little bit deeper about things. For example, we can:

- Think about the whole issue of eating meat and how it’s not a thing to get real judgmental about. It’s for us to see that different people practice in different ways.

- Think about the fact that people have different dispositions and develop some respect for them.

- Think about how important it is to have met a pure system of teachings, a pure originator of those teachings (i.e. Shakyamuni Buddha), a pure lineage, and pure practitioners who have actually gained the realizations.

- Think about how important the above is and compare it with other things that we’ve gotten interested in from time to time. Ask ourselves, “Which kind of lineage do we trust more? Which kind of teacher do we trust more?” Something that was developed last year or something that was developed 2,500 years ago?

These are all different points that we can think about. In your analytical meditation, you take these points, go through the different things we covered step-by-step, and think about them in relationship to your life and in relationship to your own spiritual path.

Questions and answers

Audience: I am confused. It seems like you are saying something like this is right and the other ones are wrong. But I don’t think that that’s what you are saying. Could you elaborate please?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Yes, I wasn’t saying that the Buddha’s path is the only path and the other ones are wrong. From the Buddhist point of view, there is some of the gradual path to enlightenment in every religion. You will see certain common elements in all religions. Whatever elements there are in other religions that lead to enlightenment, then these things are to be respected and practiced.

For example, Hinduism talks about reincarnation. That is very helpful. Now, the Buddhist view of reincarnation is slightly different from the Hindu view. But still, there are certain elements of the Hindu view that are really compatible. If we learned them, they can help us understand the Buddhist view of reincarnation. In Christianity, Jesus taught about turning the other cheek and forgiveness and patience. We would say these are Buddhist teachings. It may come out of Jesus’s mouth, but it doesn’t mean that because it comes out of somebody’s mouth, it belongs to them. These are universal teachings. They also fit in with the Buddhist path.

If you look in Islam or Judaism, I am sure you will find certain ethical principles too that very much apply to the Buddhist path. We would say those are also Buddhist teachings. Now, I don’t know how much other religions would like us to tell them that they practice parts of Buddhist teachings, but the label “Buddhist teachings” is a very general one. It doesn’t mean whatever Buddha said. It means whatever you practice that leads you on the path.

For that reason, all these different elements in the various religions are to be respected and practiced. Now, if a religion teaches something that doesn’t lead to ultimate happiness, for example, if a religion says, “It’s okay to kill animals, go ahead,” well, that part of it isn’t Buddhist teachings and we shouldn’t practice that. Or if some religion says to be sectarian, then again, we don’t practice that. We have to have a lot of discriminating wisdom. Other traditions have a lot of good things that we should adopt, but there may be some faulty things that we should just leave alone.

The Tibetans teach very much in terms of levels. In other words, the Tibetans teach that if you practice the Theravada tradition, you can attain arhatship, but just based on those teachings, you can’t attain fully enlightened buddhahood because it doesn’t have the deeper interpretation of emptiness, for example. They would say that the general Mahayana is very good, and it will lead you up to the 10th level of the bodhisattva path, but to become a fully enlightened buddha, you need to enter the Vajrayana. The Tibetans have placed it all into a systematic way.

However, I think that doesn’t mean that one teaching is really lower than another, and that if you practice one tradition, you are inferior. I remember one of my teachers saying, “You should never put down Theravada arhats because they have many more good qualities than you do.” If you look at it and face it, many of the people in that tradition who practice that path and have seen results have many more good qualities than me. This is something to respect and to learn from. Similarly with the general Mahayana path.

Also, you can’t say that because somebody is, for instance, wearing the saffron robes of Thailand or Burma, that they are not a buddha. We don’t know what that person’s realizations are. They might have the complete Madhyamaka understanding of emptiness. They might be a bodhisattva who’s manifesting in the Theravadan tradition. They might be actually, in fact, a high tantric practitioner manifesting as a Theravada teacher. How can we tell? We don’t know.

Practitioners corrupting pure teachings

[In response to audience] We always say that the problem is never really with the pure teachings of the religion. The problem is with the mistaken notions of the people who call themselves practitioners. The people who practice the religion might not be so pure. It gets all mixed in with greed, power, and so on. For example, we have people killing in the name of Christ.

Is that a danger in Buddhism coming to the West? I think it is. Why? Because we are sentient beings and our minds are completely full of pride, attachment, ignorance, jealousy, etc. As long as our minds are afflicted1, they become a danger to the pure lineage of the teachings. It’s really our own individual responsibility—if we really respect Buddha’s teachings—to try and understand them deeply and practice them from the depth of our heart so that there is a transformative effect on our mind. If there is that transformation, our minds won’t pollute the teachings. We won’t misuse them. It’s up to us individually to practice as well as we can to avoid that happening.

This is where the whole idea of lineage is really important—the importance of having a teacher (we’ll get into this subject later)—so that we don’t go off on our own trips, don’t make wrong turns. We don’t want to make Buddhism a part of pop culture and make up our own Buddhist tradition to fit our delusions—have samsara and pretend we are practicing for nirvana at the same time. This is really why it is important to have a close relationship with a teacher. We get a continuous input of accurate teachings. Our teacher can correct us if we start messing up.

Audience: To prevent this, would it help to institutionalize?

VTC: It is really difficult when a religion gets institutionalized. In one way, institutionalizing something protects the core of the teachings from everybody doing their own trip. On the other hand, once you establish an institution, you become protective and you do everything in the name of your institution. This opens you up to greed and power. It’s a delicate balancing act, it really is.

Humility in the teacher

[In response to audience] Well, I have no ability to read other people’s level of mind, but I do know of my own experience. For me, the best example of spiritual masters are people who are truly humble. I can see my pride is a problem and I can see it as a defilement. For me what is really good is a master who is very low-key and humble. I look at somebody like the Dalai Lama. The Tibetans are all going, “His Holiness is Chenrezig. He is a buddha.” But His Holiness says, “I am just a simple monk.”

What is so remarkable about His Holiness is that he is so ordinary. He doesn’t go on big ego trips. He doesn’t do all sorts of the extravagant this and that. He doesn’t say he is this and that and the other thing. When he is with a person, he is completely with that person. You can feel his compassion for that person. To me, that’s what makes him so special. Humble people in our world are very rare.

People who proclaim their qualities are numerous. I know for myself, I need a role model who is very humble. What appeals to me is the kind of teacher who shows me an example that I know I want to become.

Finding the perfect people

[In response to audience] I am glad you brought this up, because it’s something I’ve thought about a lot too. When we go into Buddhism, all the lamas are telling us about the pure tradition and how wonderful Tibet was, etc. You think, “I’ve finally found the perfect group of people. The Tibetans are so kind and they are so hospitable, they are so generous.” It’s like, “Finally, after all these hassles in the West, I found some people who are just really nice and pure.”

And then you stay for a long while. You stay, and you stay, and you begin to realize Tibet is also samsara. There’s greed, ignorance, and hatred in the Tibetan community too. Our Western bubble pops and we feel disillusioned, we feel let down. We had hoped so much to meet the perfect beings, but they wind up being ordinary people. We just feel shattered inside.

There are a few things going on. I think one is that we have incredible unrealistic expectations of finding perfect people.

First of all, in any society where there are sentient beings, there’s greed, ignorance, and hatred, and there’s going to be injustice. Second of all, our own mind is polluted. We project a lot of negative qualities onto other people. Some of the faults that we are seeing might be due to our own projections. We judge other cultures by our own preconceptualized cultural values. We hold onto democracy. We bow down to democracy and money, and we think everybody in the world should. We get disillusioned by our own expectations and preconceptions. Our judgments are based on our own preconceptions. We must not forget the fact that other cultures and people as a whole are sentient beings. They are just like us. Things aren’t going to be perfect. We should also recognize that a religious system and the system of teachings can be very perfect, but all the people who practice them may not be. Many of them may be perfect, but because of our garbage mind, we project imperfection on them. Also, many people who call themselves Buddhist may not actually be practicing Buddhism. They may not really integrate the teachings in their hearts.

There is one thing that the Westerners wonder about a lot. In a social system like in Tibet, you talk so much about bodhicitta, and the Tibetans are friendly, and they are very kind people, but why is there this whole distinction between the rich and the poor? Why were there no social institutions to show your compassion? Why didn’t everybody have good education? Why wasn’t there a public health system?

This is just the way their culture evolved. They had a completely different cultural view. They practice compassion in their way. They didn’t see practicing compassion meaning equal education for all. We do.

I think Buddhism coming to the West will take on a very different social feeling. I think the Tibetan system is changing as a result of contact with the West and our asking these kinds of questions.

Audience: Do you think it is karma, especially collective karma, at play in what happened to Tibet?

VTC: It is very possible that the people there experience the results of having to leave their country and its being occupied as a result of collective karma. Now, those people who experienced that may not have all been Tibetans when they created the cause for that experience. They may have been Chinese when they created the cause. Later they were born as Tibetans and they experienced that result. But definitely karma is involved.

Action and motivation

[In response to audience] What makes an action karmically beneficial or not beneficial is your motivation. There’s nothing cast in concrete. A lot of it depends on your motivation and your understanding. For example, if you say, “I am a high tantric practitioner,” when you are not, and use that as your justification for eating meat, that doesn’t hold water. If you go on a big trip, “I am a vegetarian. Everybody has to be vegetarian,” chances are that pride could come up. The basic thing is what is going on in the mind? What’s the motivation? What’s the understanding?

Different people are going to have different motivations approaching a certain situation. According to your motivation, a certain physical action may be beneficial or it may be harmful depending not so much on the action as on the mind that’s doing it.

Audience: Are tantric practitioners creating negative karma by eating meat?

The real tantric practitioners are not. At their level of practice, your whole intention of eating meat is because you need to keep those elements in your body strong so that you can do this very delicate meditation to realize emptiness and become a buddha. Your whole mind is directed toward enlightenment.

It’s not, “Oh, this meat tastes good and now I have an excuse to eat it.” You are using it completely for your spiritual practice. Also the people at this level of the path, they are saying mantras over the meat, they are making prayers for the animal, “May I be able to lead this animal to full enlightenment.” It’s very different from some guy who pulls up at McDonald’s and eats five hamburgers. A tantric practitioner isn’t like that. If somebody rationalizes it, that’s a completely different ball game.

What the precept of not killing involves

[In response to audience] Now there are different ways of presenting this subject. They say if you kill a living being, if you ask somebody else to kill it, or if you know it was killed specifically for you, then you have karma involved in the precept of not killing. For that reason, that meat should not be eaten. The lamas usually say just that.

Then the Westerners say, “But what about meat that is already in the supermarket that is killed?” The lamas say, “That’s okay.” And then the Westerners say, “But you are going there to buy it, therefore you are killing it.” Then the lamas answer, “Yes, but you didn’t ask that specific person to kill that for you. They had already done that and you happened to come into the supermarket and get it.” There is a difference involving the karma of killing whether you have the direct influence of having this animal killed for you or doing it yourself or whatever.

“Afflicted” is the translation that Venerable Thubten Chodron now uses in place of “deluded.” ↩

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.